Democratic Myths in Myanmar's Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRENDS in MANDALAY Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY Photo credits Paul van Hoof Mithulina Chatterjee Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 11 2. Methodology 14 2.1 Objectives 15 2.2 Research tools 15 3. Introduction to Mandalay region and participating townships 18 3.1 Socio-economic context 20 3.2 Demographics 22 3.3 Historical context 23 3.4 Governance institutions 26 3.5 Introduction to the three townships participating in the mapping 33 4. Governance at the frontline: Participation in planning, responsiveness for local service provision and accountability 38 4.1 Recent developments in Mandalay region from a citizen’s perspective 39 4.1.1 Citizens views on improvements in their village tract or ward 39 4.1.2 Citizens views on challenges in their village tract or ward 40 4.1.3 Perceptions on safety and security in Mandalay Region 43 4.2 Development planning and citizen participation 46 4.2.1 Planning, implementation and monitoring of development fund projects 48 4.2.2 Participation of citizens in decision-making regarding the utilisation of the development funds 52 4.3 Access to services 58 4.3.1 Basic healthcare service 62 4.3.2 Primary education 74 4.3.3 Drinking water 83 4.4 Information, transparency and accountability 94 4.4.1 Aspects of institutional and social accountability 95 4.4.2 Transparency and access to information 102 4.4.3 Civil society’s role in enhancing transparency and accountability 106 5. -

2 December 2020 1 2 Dec 20 Gnlm

FIRM COMMITMENT KEY TO REDUCING RISK OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING DURING POST COVID-19 PERIOD PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Myanmar to join new Senior Officials Figures and percentages of 2020 Multiparty Democracy Counterterrorism Policy Forum General Election to be published in newspapers PAGE-6 PAGE-10 Vol. VII, No. 230, 3rd Waning of Tazaungmon 1382 ME www.gnlm.com.mm, www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Wednesday, 2 December 2020 University of Yangon holds 100th anniversary celebrations State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, Vice-President U Myint Swe, Amyotha Hluttaw Speaker Mahn Win Khaing Than, Union Ministers, Yangon Region Chief Minister and YU Rector are virtually cutting the ceremonial ribbon for 100th anniversary of Yangon University. PHOTO : MNA HE 100th anniversary Dr Phoe Kaung used a virtual congratulatory remark on the Kyi (now the State Counsellor) gence in appointment, transfer of University of Yangon system in cutting the ceremonial ceremony. for ‘Drawing University New Act and promotion of academic staff was held on virtual cel- ribbon of the opening ceremony. (Congratulatory speech of and Upgrade of Yangon Univer- and other issues in relation to the Tebrations yesterday. State Counsellor Daw Aung Amyotha Hluttaw Speaker is sity (Main)’ ; she led the commit- academic sector, administrative After the opening ceremony San Suu Kyi, in her capacity as covered on page 5 ) tee that worked for upgrade and sector and infrastructural devel- of the event with the song enti- the Chairperson of Steering Union Minister for Educa- renovation of the university in opment of the university by draw- tled ‘Centenary Celebrations of Committee on Organizing Cen- tion, the secretary of the steer- line with international standards. -

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020 Contract Number: 72048218C00004 Myanmar Analytical Activity Acknowledgement This report has been written by Kimetrica LLC (www.kimetrica.com) and Mekong Economics (www.mekongeconomics.com) as part of the Myanmar Analytical Activity, and is therefore the exclusive property of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Melissa Earl (Kimetrica) is the author of this report and reachable at [email protected] or at Kimetrica LLC, 80 Garden Center, Suite A-368, Broomfield, CO 80020. The author’s views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID.GOV DECEMBER 2019 MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT | 1 JANUARY 2020 AT A GLANCE Myanmar’s ICOE Finds Insufficient Evidence of Genocide. The ICOE admits there is evidence that Tatmadaw soldiers committed individual war crimes, but rules there is no evidence of a systematic effort to destroy the Rohingya people. (Page 1) The ICJ Rules Myanmar Must Take Measures to Protect the Rohingya From Acts of Genocide. International observers laud the ruling as a major step toward fighting genocide globally, but reactions to the ruling in Myanmar are mixed. (Page 2) Fortify Rights Documents Five Cases of Rohingya IDPs Forced to Accept NVCs. The international community and the Rohingya condemned the cards, saying they are a means to keep the Rohingya from obtaining full citizenship rights by identifying them as “Bengali,” not Rohingya. (Page 3) During the Chinese President’s State Visit to Myanmar, the Two Countries Signed Multiple MoUs. The 33 MoUs that President Xi Jinping cosigned are related to infrastructure, trade, media, and urban development. -

DASHED HOPES the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DASHED HOPES The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Background ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Section 66(d) -

No 667/2005 of 28 April 2005 Amending Council Regulation (EC) No 798/2004 Renewing the Restrictive Measures in Respect of Burma/Myanmar

29.4.2005EN Official Journal of the European Union L 108/35 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 667/2005 of 28 April 2005 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 798/2004 renewing the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (4) Article 12(b) of Regulation (EC) No 798/2004 empowers the Commission to amend Annexes III and IV on the Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European basis of decisions taken in respect of Annexes I and II Community, to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (2), renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar. Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 798/2004 of 26 April 2004 renewing the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar (1), and in particular Article 12 thereof, (5) Common Position 2005/340/CFSP (3) amends Annexes I and II to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP. Annexes III Whereas: and IV to Regulation (EC) No 798/2004 should, therefore, be amended accordingly. In order to ensure (1) Annex II to Regulation (EC) No 798/2004 lists the that the measures provided for in this Regulation are competent authorities to which specific functions effective, this Regulation must enter into force imme- related to the implementation of that regulation are diately, attributed. Article 12(a) of Regulation (EC) No 798/2004 empowers the Commission to amend Annex II on the basis of information supplied by Member States. HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Belgium, Hungary, the Netherlands and Sweden have informed the Commission of changes regarding their competent authorities. Annex II to Regulation (EC) No Article 1 798/2004 should, therefore, be amended. -

Acts Adopted Under Title V of the Treaty on European Union)

L 108/88EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2005 (Acts adopted under Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2005/340/CFSP of 25 April 2005 extending restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Common Position 2004/423/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (8) In the event of a substantial improvement in the overall political situation in Burma/Myanmar, the suspension of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in these restrictive measures and a gradual resumption of particular Article 15 thereof, cooperation with Burma/Myanmar will be considered, after the Council has assessed developments. Whereas: (9) Action by the Community is needed in order to (1) On 26 April 2004, the Council adopted Common implement some of these measures, Position 2004/423/CFSP renewing restrictive measures 1 against Burma/Myanmar ( ). HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (2) On 25 October 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/730/CFSP on additional restrictive Article 1 measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Annexes I and II to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP shall be Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (2). replaced by Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (3) On 21 February 2005, the Council adopted Common Position 2005/149/CFSP amending Annex II to Article 2 Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (3). Common Position 2004/423/CFSP is hereby renewed for a period of 12 months. (4) The Council would recall its position on the political situation in Burma/Myanmar and considers that recent developments do not justify suspension of the restrictive Article 3 measures. -

Myanmar's 2020 Election: the COMPETING INTERESTS of CHINA and INDIA

Myanmar's 2020 Election: THE COMPETING INTERESTS OF CHINA AND INDIA By Yan Myo Thein |Independent Analyst| October 2020 About the Report This report evaluates the competing interests of China and India in Myanmar’s 2020 General Election based on the current and historical documents, media reportages and online interviews, relevant to the multiparty general elections in Myanmar (Burma). The United States Institute of Peace (USIP) provided financial support to the research. About the Author Yan Myo Thein, a former political prisoner, is a political commentator cum analyst as well as an independent researcher, based in Yangon (Rangoon), Myanmar (Burma), who has covered Myanmar (Burma)’s making of a democratic federal union, peacebuilding and foreign relations, especially its ties with China and India for more than twenty years. He now writes for the local daily newspapers, the Daily Eleven and the 7th Day Daily in Myanmar and makes the political insights on Myanmar (Burma) for the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), VOA, RFA and BBC. 1 Contents Summary ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Myanmar Election and China ...................................................................................................................... 6 Overview of History ............................................................................................................................... -

Commission Regulation (EC)

L 108/20 EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2009 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (3) Common Position 2009/351/CFSP of 27 April 2009 ( 2 ) amends Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006. Annexes VI and VII Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 should, therefore, be Community, amended accordingly. Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 of (4) In order to ensure that the measures provided for in this 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive Regulation are effective, this Regulation should enter into measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regu- force immediately, lation (EC) No 817/2006 ( 1), and in particular Article 18(1)(b) thereof, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Whereas: Article 1 1. Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby (1) Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists the replaced by the text of Annex I to this Regulation. persons, groups and entities covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that Regulation. 2. Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby replaced by the text of Annex II to this Regulation. (2) Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists enter- prises owned or controlled by the Government of Article 2 Burma/Myanmar or its members or persons associated with them, subject to restrictions on investment under This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its publi- that Regulation. -

Myanmar Military Should End Its Use of Violence and Respect Democracy

Myanmar military should end its use of violence and respect democracy The undersigned groups today denounced an apparent coup in Myanmar, and associated violence, which has suspended civilian government and effectively returned full power to the military. On 1 February, the military arbitrarily detained State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and other leaders of the National League for Democracy. A year-long state of emergency was declared, installing Vice-President and former lieutenant-general Myint Swe as the acting President. Myint Swe immediately handed over power to commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing (Section 418 of Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution enables transfer of legislative, executive, and judicial powers to the Commander in Chief). Internet connections and phone lines throughout the country were disrupted, pro-democracy activists have been arbitrarily arrested, with incoming reports of increased detentions. Soldiers in armored cars have been visibly roaming Nay Pyi Taw and Yangon, raising fears of lethal violence. “The military should immediately and unconditionally release all detained and return to Parliament to reach a peaceful resolution with all relevant parties,” said the groups. The military and its aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) had disputed the results of the November elections, which saw the majority of the seats won by the NLD. The arrests of the leaders came just before the Parliament was due to convene for the first time in order to pick the President and Vice-Presidents. Among the key leaders arrested, aside from Aung San Suu Kyi, are: President U Win Myint and Chief Ministers U Phyo Min Thein, Dr Zaw Myint Maung, Dr Aung Moe Nyo, Daw Nan Khin Htwe Myint, and U Nyi Pu. -

News Bulletin

State and Region Parliaments News Bulletin Issue (44) _ Thursday, 30th November 2017 Hluttaw Reduced 20 Billion MMK from the Appropriation for Investment of Ayeyarwady Regional Gov’t November 15, 2017 According to the Public Budget, appropriations and plans, Hluttaw was lakhsAccording to buy policeto the traffic Public cars forAccount, Chief Planning and Finance, Economic and reported to amend and draw the PlanningMinister wereand reviewed.Finance, Economic and Trade Development Committee, 20 budget plan with over 162 billion by billion MMK from the budget appropriation reducing the rest 20 billion. A member of parliament said that as Trade Development Committee, it was there were requests not only for the known that what the regional government for 2018-2019 financial year submitted plans actually needed to be carried out fromsubmitted April, to2018 the to regional September, Hluttaw 2018 5 and for by Ayeyarwady regional government for the sake of Public but also for 2018 – 2019 financial year: part one is- were reduced by Regional Hluttaw. - buying materials and furniture for U Aung Thu Htwe, the head of that office use, cars and major repairs of part two is from October, 2018 to Sep committee, said that the budget appro cars, the heads of the respective tember, 2019, Hluttaw approved only the priation for the financial year divided departments were asked to report and total appropriation for investment and into two parts was submitted. There explain in the session of Hluttaw the rest will be approved by Hluttaw by were over 182 billion for the appropriation Committee and the request of capital drawing Referencethe detailed : The Voice Dailybudget plan from October, 2018 to September, 2019. -

Network for Democracy and Development Weekly Political

Generated by Foxit PDF Creator © Foxit Software http://www.foxitsoftware.com For evaluation only. NDD-Documentation and Research Department NNeettwwoorrkk ffoorr DDeemmooccrraaccyy aanndd DDeevveellooppmmeenntt DDooccuummeennttaattiiioonn aanndd RReesseeaarrcchh DDeeppaarrttmmeenntt P.O Box 179, Mae Sod, Tak, 63110, Thailand. Phone: +66 85-733 4303. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] WWeeeekklllyy PPoollliiittiiiccaalll EEvveennttss RReeggaarrddiiinngg tthhee SSPPDDCC'''ss EEllleeccttiiioonn ((002288///22001100)) August 01 – August 07, 2010 STATE PEACE AND DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL (SPDC) AND ITS STOOGE ORGANIZATIONS -Residents of Karen State say that since the beginning of August, SPDC troops operating in most of Karen State areas have placed more restrictions on local people in the lead up to the elections. Restrictions include, preventing them from going out of their villages, investigating people while on trips, asking for family registration lists, taking records and even asking for money. (KIC 030810) -A young person, close to the Chinese Temple, states that the administrative team of the Chinese Temple in Mogaung Township, Kachin State, helped Chinese people in Mogaung area obtain national IDs, and influential Chinese residents of Mogaung were forced to become became Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) party members, and wear the party uniforms, in an effort to persuade the rest of the Chinese people in the area to join the USDP. (NEJ 030810) -A military official who attended the State Security Meeting held on 1 August stated that Lt. Gen. Myint Swe from the Ministry of Defense had ordered a tightening of security for an important event, and it seemed that he mentioned the elections will possibly be in December 2010. -

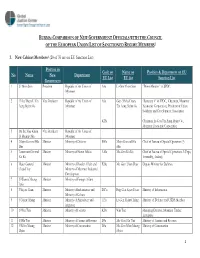

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry