Individual Reactions of Permanganate and Various Reductants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carbonyl Compounds

Carbonyl Compounds What are Carbonyl Compounds? Carbonyl compounds are compounds that contain the C=O (carbonyl) group. Preparation of Aldehydes: 1. Preparation from Acid Chloride (Rosenmund Reduction): This reaction was named after Karl Wilhelm Rosenmund, who first reported it in 1918. The reaction is a hydrogenation process in which an acyl chloride is selectively reduced to an aldehyde. The reaction, a hydrogenolysis, is catalysed by palladium on barium sulfate, which is sometimes called the Rosenmund catalyst. 2. Preparation from Nitriles: This reaction involves the preparation of aldehydes (R-CHO) from nitriles (R- CN) using SnCl2 and HCl and quenching the resulting iminium salt ([R- + − CH=NH2] Cl ) with water (H2O). During the synthesis, ammonium chloride is also produced. The reaction is known as Stephen Aldehyde synthesis. Dr. Sumi Ganguly Page 1 3. Preparation from Grignard Reagent: When Grignard Reagent is reacted with HCN followed by hydrolysis aldehyde is produced. Preparation of Ketones: 1. Preparation from Acid Chloride (Friedel-Crafts Acylation): Acid chlorides when reacted with benzene in presence of anhydrous AlCl3, aromatic ketone are produced. However, only aromatic ketones can be prepared by following this method. In order to prepare both aromatic and aliphatic ketones acid chlorides is reacted with lithium dialkylcuprate (Gilman Reagnt). Dr. Sumi Ganguly Page 2 The lithium dialkyl cuprate is produced by the reaction of two equivalents of the organolithium reagent with copper (I) iodide. Example: 3. Preparation from Nitriles and Grignard Reagents: When Grignard Reagent is reacted with RCN followed by hydrolysis aldehyde is produced. Dr. Sumi Ganguly Page 3 Physical Characteristic of Carbonyl Compounds: 1) The boiling point of carbonyl compounds is higher than the alkanes with similar Mr. -

Decolorization of Reactive Orange 16 Via Ferrate(VI) Oxidation Assisted by Sonication

Turkish Journal of Chemistry Turk J Chem (2017) 41: 577 { 586 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/chem/ ⃝c TUB¨ ITAK_ Research Article doi:10.3906/kim-1701-8 Decolorization of reactive orange 16 via ferrate(VI) oxidation assisted by sonication Serkan S¸AHINKAYA_ ∗ Department of Environmental Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Nev¸sehirHacı Bekta¸sVeli University, Nev¸sehir,Turkey Received: 02.01.2017 • Accepted/Published Online: 24.03.2017 • Final Version: 05.09.2017 Abstract: The decolorization of azo dye C.I. reactive orange 16 (RO 16) via ferrate(VI) and sono-ferrate(VI) methods, which is the combination of the ferrate(VI) oxidation method with sonication, has been achieved in the present study. The influences of some important operating parameters, which are the initial pH, the concentration of potassium ferrate(VI) (K 2 FeO 4) and the RO 16 dye, and ultrasonic density (for only the sono-ferrate(VI) method), on the color removal have −1 been investigated. The optimum conditions have been determined as pH = 7 and [K 2 FeO 4 ] = 50 mg L for the −1 −1 individual ferrate(VI) oxidation method and pH = 7 and [K 2 FeO 4 ] = 50 mg L by direct sonication at 0.50 W mL ultrasonic density and 20 kHz fixed frequency for the sono-ferrate(VI) method. The color removal efficiencies were 85% by ferrate(VI) method and 91% by sono-ferrate(VI) method. Kinetic studies were also performed for the decolorization of RO 16 under the optimized conditions at room temperature. It was seen that the oxidative decolorization of RO 16 via the sono-ferrate(VI) method happened more rapidly because of the production of OH • radical through sonication compared to the individual ferrate(VI) method. -

Exactly As Received Mic 61-929 MERRYMAN, Earl L Ew Is. THE

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received Mic 61-929 MERRYMAN, Earl Lewis. THE ISOTOPIC EXCHANGE REACTION BETWEEN Mn AND MnO” . 4 The Ohio State University, Ph.D, 1960 Chemistry, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE ISOTOPIC EXCHANGE REACTION BETTAIEEN Mn** AND ItaO ^ DISSERTATION Presented in P&rtial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of The Ohio S tate U niversity By Earl Lewis Ferryman, B.Sc* The Ohio State University I960 Approved by Department oy Chenletry 1C mnriEDGiBiT The author wlshea to e:qpr«as his approoiation to Profoaaor Alfred B. Garrett for hie superrieion and enocur- agement during the oouree of this research* and for his sincere interest in mj eelfare both as an undergraduate and graduate student at Ohio State University. I also wish to thank the Ohio State University Cheidstry Depsurtnent for the Assistant ships granted me during the 1 9 5 6* 7 "^ aeademlo years. The author also gratefully acknowledges the Fellowships granted me by the American Cyansuald Company during the 1959*60 academic year and by the National Science Foundation during the Summer Q u a rte r of I960* i i TABI£ OP CONTEHTS PAOE INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 Àpplloationa of Radloaotirlty in Chomiatry 1 The Problem and Its H latory ....................................................... .. 1 The Problem Reeulting from Early Work 5 Statement of the Problem .......................... -

Kinetic Studies on Permanganate Oxidation of Acetophenones Under

Indi an Journal of Chemistry Vol. 40A, June 2001, pp. 610-612 Kinetic studies on permanganate oxidation of The ketones were further purified by vacuum acetophenones under phase transfer catalysis distillation. The solvents employed were purified by standard methods and doubly distilled water was P S Sheeba & T D Radhakrishnan Nair* always used. The catalysts used were tricapryl Department of Chemistry, Calicut University methylammonium chloride (TCMAC) and tetrabutyl Calicut University P.O., Kerala 673 635. India ammonium bromide (TBAB). The former has Received 18 October 2000; revised 8 March 2001 relatively larger organic structure (C 10H21 )JN+CH 3Cr compared to the latter (C4 H9) 4N+B(. Kinetic studies on the permanganate oxidation of The solutions containing the permanganate ions in acetopheno_ne and some of its substituents in organic media using the organic solvents were prepared by shaking the techn1que of phase transfer catalysis are reported. aqueous potassium permanganate solution with the Tncaprylmethylammonium chloride and tetrabutylammonium bromide have been used as the phase transfer catalysts. The organic solvents contammg the phase transfer 4 reaction shows first order dependence each on [ketones] and the catalysts as reported elsewhere . The solutions of the [permanganate ions] respectively . The rate coefficients fit well oxidant thus prepared in the organic solvent and the with the Hammett equation and the p-value calculated aorees well substrate in the organic solvent were thermally with the reaction requirements. "' equilibrated (± 0.05°C) at the desired temperature for Potassium permanganate is a powerful oxidizing about half an hour before mixing. Kinetic runs were carried out under pseudo-first order conditions. -

Manufacturing of Potassium Permanganate Kmno4 This Is the Most Important and Well Known Salt of Permanganic Acid

Manufacturing of Potassium Permanganate KMnO4 This is the most important and well known salt of permanganic acid. It is prepared from the pyrolusite ore. It is prepared by fusing pyrolusite ore either with KOH or K2CO3 in presence of atmospheric oxygen or any other oxidising agent such as KNO3. The mass turns green with the formation of potassium manganate, K2MnO4. 2MnO2 + 4KOH + O2 →2K2MnO4 + 2H2O 2MnO2 + 2K2CO3 + O2 →2K2MnO4 + 2CO2 The fused mass is extracted with water. The solution is now treated with a current of chlorine or ozone or carbon dioxide to convert manganate into permanganate. 2K2MnO4 + Cl2 → 2KMnO4 + 2KCl 2K2MnO4 + H2O + O3 → 2KMnO4 + 2KOH + O2 3K2MnO4 + 2CO2 → 2KMnO4 + MnO2 + 2K2CO3 Now-a-days, the conversion is done electrolytically. It is electrolysed between iron cathode and nickel anode. Dilute alkali solution is taken in the cathodic compartment and potassium manganate solution is taken in the anodic compartment. Both the compartments are separated by a diaphragm. On passing current, the oxygen evolved at anode oxidises manganate into permanganate. At anode: 2K2MnO4 + H2O + O → 2KMnO4 + 2KOH 2- - - MnO4 → MnO4 + e + - At cathode: 2H + 2e → H2 Properties: It is purple coloured crystalline compound. It is fairly soluble in water. When heated alone or with an alkali, it decomposes evolving oxygen. 2KMnO4 → K2MnO4 + MnO2 + O2 4KMnO4 + 4KOH → 4K2MnO4 + 2H2O + O2 On treatment with conc. H2SO4, it forms manganese heptoxide via permanganyl sulphate which decomposes explosively on heating. 2KMnO4+3H2SO4 → 2KHSO4 + (MnO3)2SO4 + 2H2O (MnO3)2SO4 + H2O → Mn2O7 + H2SO4 Mn2O7 → 2MnO2 + 3/2O2 Potassium permanganate is a powerful oxidising agent. A mixture of sulphur, charcoal and KMnO4 forms an explosive powder. -

Revision Guide

Revision Guide Chemistry - Unit 3 Physical and Inorganic Chemistry GCE A Level WJEC These notes have been authored by experienced teachers and are provided as support to students revising for their GCE A level exams. Though the resources are comprehensive, they may not cover every aspect of the specification and do not represent the depth of knowledge required for each unit of work. 1 Content Page Section 2 3.1 – Redox and standard electrode potential 13 3.2 - Redox reactions 20 3.3 - Chemistry of the p-block 30 3.4 - Chemistry of the d-block transition metals 35 3.5 - Chemical kinetics 44 3.6 - Enthalpy changes for solids and solutions 50 3.7 - Entropy and feasibility of reactions 53 3.8 - Equilibrium constants 57 3.9 - Acid-base equilibria 66 Acknowledgements 2 3.1 – Redox and standard electrode potential Redox reactions In AS, we saw that in redox reactions, something is oxidised and something else is reduced (remember OILRIG – this deals with loss and gain of electrons). Another way that we can determine if a redox reaction has happened is by using oxidation states or numbers (see AS revision guide pages 2 and 44). You need to know that: - • oxidation is loss of electrons • reduction is gain of electrons • an oxidising agent is a species that accepts electrons, thereby helping oxidation. It becomes reduced itself in the process. • a reducing agent is a species that donates electrons, thereby helping reduction. It becomes oxidised itself in the process. You also should remember these rules for assigning oxidation numbers in a compound: - 1 All elements have an oxidation number of zero (including diatomic molecules like H2) 2 Hydrogen is 1 unless it’s with a Group 1 metal, then it’s -1 3 Oxygen is -2 (unless it’s a peroxide when it’s -1, or reacted with fluorine, when it’s +2). -

Electrochemical Control of Organic Reactions Involving Phase Transfer

University College London Department of Chemistry Electrochemical Control of Organic Reactions Involving Phase Transfer by Camilla Forssten Ph.D. 2002 ProQuest Number: U643499 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U643499 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Phase transfer catalysis reactions are reactions where the reactants are soluble in different solvents. The phase transfer catalyst facilitates the transfer of a reactant from one phase to another, hence enabling the reaction. This can be explained electrochemically: By partitioning between the phases, the catalyst establishes a potential difference across the interface, which drives the transfer of reagent into the other phase (usually an inorganic anion is being transferred into the organic phase), or controls the reaction at the interface. A similar potential difference can also be applied with electrochemical instrumentation and the reactions can be investigated in electrochemical systems. Electrochemistry at ITIES (Interface between Two Immiscible Electrolyte Solutions) provides a fast, convenient and simple way of investigating the electrochemistry of a synthetic phase transfer reaction. The organic syntheses were also carried out to confirm the electrochemical results. -

CHM 4 Naming Compounds Extra Practice: Version C When You Are

CHM 4 Naming Compounds Extra Practice: Version C When you are done, grade yourself using the answer key on the next page. To be well prepared for Exam #1, you should be scoring ≥85% on your naming practice. Converting from name to formula 1) What is the formula for sulfurous acid? A) H3SO3(aq) B) H2S(aq) C) H2SO3(aq) D) H3SO4(aq) E) H2SO4(aq) 2) What is the formula for rubidium arsenate? A) Rb2AsO4 B) Rb2AsO3 C) Rb3AsO3 D) Rb3AsO4 E) RbAsO3 3) What is the formula for aluminum sulfide? A) Al(SO3)2 B) Al(SO2)2 C) Al3S2 D) AlSO2 E) Al2S3 4) What is the formula for oxalic acid? A) H2C4O2 (aq) B) HC2H2O3 (aq) C) H2C2O4 (aq) D) HC2H3O2 (aq) E) HC2O4 (aq) 5) What is the formula for zinc borate? A) ZnBO4 B) Zn3(BO3)2 C) Zn(BO4)2 D) Zn3BO3 E) Zn2BO3 6) What is the formula for tin(II) chromate? A) SnCrO4 B) Sn2Cr2O7 C) SnCr2O4 D) Sn2CrO4 E) SnCr2O7 7) What is the formula for hydrobromic acid? A) H2BrO3 (aq) B) HBrO (aq) C) HBrO2 (aq) D) HBrO3 (aq) E) HBr (aq) 8) What is the formula for tetraphosphorous pentachloride? A) P3Cl6 B) P3(ClO)6 C) P4Cl5 D) P6(ClO)3 E) P3(ClO)5 9) What is the formula for barium dihydrogen phosphate? A) BaH2PO4 B) Ba2(HPO4)3 C) Ba(HPO3)2 D) Ba3(HPO3)2 E) Ba(H2PO4)2 10) What is the formula for potassium hydroxide? A) KOH B) K3O2 C) K3OH D) K2OH E) K2O2 Converting from formula to name 11) What is the name for LiHCO3? A) lithium carbonate B) lithium hydrogen carbonate C) lithium hydrocarbide D) lithium monohydrogen monocarbide E) lithium hydrocarbonic acid 12) What is the name for HIO(aq)? A) hydroiodic acid B) periodic acid -

(III)-Catalysed Oxidation of Atenolol by Alkaline Permanganate (Sto

J. Chem. Sci., Vol. 117, No. 1, January 2005, pp. 33–42. © Indian Academy of Sciences. Kinetic, mechanistic and spectral investigation of ruthenium (III)- catalysed oxidation of atenolol by alkaline permanganate (stopped-flow technique) RAHAMATALLA M MULLA, GURUBASAVARAJ C HIREMATH and SHARANAPPA T NANDIBEWOOR* PG Department of Studies in Chemistry, Karnatak University, Dharwad 580 003, India e-mail: [email protected] MS received 10 October 2003; revised 26 December 2003 Abstract. Kinetics of ruthenium (III) catalyzed oxidation of atenolol by permanganate in alkaline medium at constant ionic strength of 0×30 mol dm3 has been studied spectrophotometrically using a rapid kinetic accessory. Reaction between permanganate and atenolol in alkaline medium exhibits 1 : 8 stoichiometry (atenolol : KMnO4). The reaction shows first-order dependence on [permanganate] and [ruthenium (III)] and apparently less than unit order on both atenolol and alkali concentrations. Reaction rate decreases with increase in ionic strength and increases with decreasing dielectric constant of the medium. Initial addition of reaction products does not affect the rate significantly. A mechanism involving the formation of a complex between catalyst and substrate has been proposed. The active species of ruthenium (III) is 2+ understood as [Ru(H2O)5OH] . The reaction constants involved in the different steps of mechanism are calculated. Activation parameters with respect to the slow step of the mechanism are computed and dis- cussed and thermodynamic quantities are also calculated. Keywords. Kinetics; permanganate; stopped-flow technique; oxidation of atenolol; ruthenium(III) catalysis. 1. Introduction (scheme 1) and one in which a hypomanganate is formed in a two-electron step followed by rapid re- Permanganates ions oxidize a greater variety of sub- action12 (scheme 2). -

Experiment: Determination of Manganese in Steel

p.1 of 4 Chemistry 201 – Winter 2007 Experiment: Determination of Manganese in Steel Manganese (Mn) in steel may be determined upon dissolution as manganese (VII) after oxidation from the manganese oxidation state (II). This procedure calls for three oxidizing agents. Manganese (VII) may be determined spectrophotometrically. During dissolution of the sample with dilute nitric acid to form iron (II) and manganese (II), nitrogen oxide gases are formed. These must be removed, partially by boiling, and the rest with ammonium peroxydisulfate which also removes carbon or other organic matter present. The nitrogen oxides may react with periodic acid which is used to convert manganese to the (VII) oxidation state. Excess peroxydisulfate is decomposed by boiling. The equations are: - + 2+ 3 Mn + 2 NO3 + 8H ---> 3 Mn + 2 NO (g) + 4H2O 2- - 2- + 2 NO2 (g) + S2O8 + 2 H2O ---> 2 NO3 + 2 SO4 + 4 H 2- 2- + 2 S2O8 + 2 H2O + heat ---> 4 SO4 + O2 + 4 H 2+ - - + - 2 Mn + 5 IO4 + 3 H2O ---> 2 MnO4 + 6 H + 5 IO3 NO(colorless gas) + 1/2 O2 (g) <---> NO2 (brown gas) Note: Peroxydisulfate has the required oxidizing potential to change the oxidation state of manganese from (II) to (IV), but the reaction is too slow. Silver could be employed catalytically but the results are too erratic. Periodate oxidizes the manganese to the (VII) state quantitatively and rapidly at the boiling point, and it is advisable to add the sparingly soluble periodate salt in several portions to maintain an excess and to allow for some decomposition of the latter salt at the elevated temperatures. -

A Manganate Ester Hydrolysis Mn(IV)

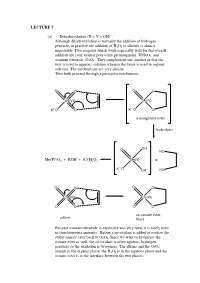

LECTURE 7 (a) Dihydroxylation (X = Y = OH) Although dihydroxylation is formally the addition of hydrogen peroxide, in practice the addition of H2O2 to alkenes is almost impossible. Two reagents which work especially well for this overall addition are cold, neutral potassium permanganate, KMnO4, and osmium tetroxide, OsO4. They complement one another in that the first is used in aqueous solution whereas the latter is used in organic solvents. The mechanisms are very similar. Thus both proceed through a pericyclic mechanism: O O O O Mn(VII) Mn(V) +- K+-O O K O O a manganate ester hydrolysis O OH HO Mn(IV)O2 + KOH + 0.5 H2O2 Mn(V) + +- K O OH HO O O O O Os(VIII) Os(VI) O O O O an osmate ester, yellow black Because osmium tetroxide is expensive and very toxic it is rarely used in stoichiometric amounts. Rather a co-oxidant is added to oxidise the stable osmate ester back to OsO4. Since we want to hydrolyse the osmate ester as well, the co-oxidant is often aqueous hydrogen peroxide so the oxidation is two-phase. The alkene and the OsO4 remain in the organic phase, the H2O2 is in the aqueous phase and the osmate ester is at the interface between the two phases: H OH H OH H OsO4, + aq.H2O2, CH Cl H 2 2 OH H H OH (c) Epoxidation (X = Y = O) The reaction of alkenes with peroxy acids (RCO3H) leads to a cyclic ether, known as an epoxide, as follows: R R O O O H O H O O Although the reaction will work with peroxyacetic acid (R = Me) it works best with peroxy acids bearing electron-withdrawing groups e.g. -

Kinetics and Mechanistic Study of the Ruthenium(III) Catalysed Oxidative Decarboxylation of L-Proline by Alkaline Heptavalent Manganese (Stopped Flow Technique)

CODEN ECJHAO E-Journal of Chemistry http://www.e-journals.net Vol. 2, No. 1, pp 91 -100, January 2005 Kinetics and Mechanistic Study of the Ruthenium(III) Catalysed Oxidative Decarboxylation of L-Proline by Alkaline Heptavalent Manganese (Stopped flow technique) R.S.SHETTAR, M.I.HIREMATH and S.T. NANDIBEWOOR* P.G. Department of Studies in Chemistry, Karnatak University, Dharwad-580003, India. Received 7 October 2004; Accepted 14 December 2004 Abstract The kinetics of ruthenium(III) catalysed oxidation of L-Proline by permanganate in alkaline medium at a constant ionic strength has been studied spectrophotometrically using a rapid kinetic accessory. The reaction between permanganate and L-Proline in alkaline medium exhibits 2:1 stoichiometry (KMnO4: L-Proline). The reaction shows first order dependence on [permanganate] and [ruthenium(III)] and apparent less than unit order dependence each in L-Proline and alkali concentrations. Reaction rate increases with increase in ionic strength and decrease in solvent polarity of the medium. Initial addition of reaction products did not affect the rate significantly. A mechanism involving the formation of a complex between catalyst and substrate has been proposed. The activation parameters were computed with respect to the slow step of the mechanism and discussed. Key words: Kinetics; Potassium permanganate Ruthenium; Oxidation; L-proline Introduction Potassium permanganate is widely used as an oxidising agent in synthetic as well as in analytical chemistry and also as a disinfectant. The reactions with permanganate are governed by pH of the medium. Among six oxidation states of manganese from 2+ to 7+, permanganate, Mn(VII) is the most potent oxidation state in acid as well as in alkaline medium.