Synopsis of the Gold House Trilogy (8) Pages-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

1 Running Head: SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY of TEXAS

Running Head: SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY OF TEXAS MIDDLE PERMIAN PLATFORM CARBONATES OUTCROP-BASED CHARACTERiZATION OF LEONARDIAN PLATFORM CARBONATE IN WEST TEXAS: IMPLICATIONS FOR SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHIC STYLES IN TRANSITIONAL ICEHOUSE-GREENHOUSE SETTINGS Stephen C. Ruppel, W. Bruce Ward1, and Eduardo E. Ariza Bureau of Economic Geology The University of Texas at Austin 1 Current address: Earthworks LLC, P.O. Box 178, Newtown, CT 06470-0178 1 ABSTRACT The Sierra Diablo Mountains of West Texas contain world class exposures of lower and middle Permian platform carbonates. As such these outcrops offer key insights into the products of carbonate deposition in the transitional icehouse/greenhouse setting of the early-mid Permian that are available in few other places in the world. They also afford an excellent basis for examing how styles of facies and sequence development vary between platform tops and platform margins. Using outcrop data and observations from over 2 mi (3 km) of continuous exposure, we collected detailed data on the facies composition and architecture of high frequency (cycle-scale) and intermediate frequency (high frequency sequence scale) successions within the Leonardian. We used these data to define facies stacking patterns along depositional dip across the platform in both low and high accommodation settings and to document how these patterns vary systematically between and within sequences . These data not only provide a basis for interpreting similar Leonardian platform successions from less well constrained outcrop and subsurface data sets but also point out some important caveats that should be considered serve as an important model for understanding depositional processes during the is part of the Permian worldwide. -

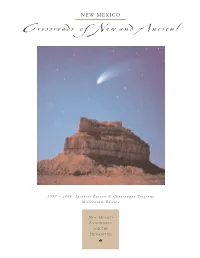

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

Click Here to View ALI SER2015 Presentation

... ali collaboratively develops innovative methods to produce real change on the ground ... both for the benefit of local communities and the landscapes upon which they rely ... intermittent system function: a key driver for restoring socio-ecological watershed resiliency in the Southwestern United States authors: c. maxwell 1, r. davidson 1, w. fleming 2 1alamosa land institute, monticello, nm, united states, 2school of architecture + planning, community & regional planning department, university of new mexico, albuquerque, us cañada alamosa watershed southwestern united states natural drivers - disturbances - floods, erosion, and aridity land of extremes rural working landscapes geronimo victorio lozen victorio peak warm spring apache in 1913: “The whole country, once so fertile and green, was now entirely barren. Gravel had washed down, covering all the nice valleys and pastures, even filling up the Warm Springs, which had completely vanished. The reservation was entirely ruined” (Betzinez, 1959). chiricahua warm springs apache homeland settlement of west - massive resource withdrawal THOUSAND HEAD 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 railroad 0 1850 60 70 80 90 1900 10 20 30 1935 CATTLE IN NEW MEXICO, 1850-1935 opened markets for cattle 1880’s known as the “great barbecue” this drought ended traditional flood-water farming in the main valleys throughout present-day New Mexico (Bryan, 1929). conciding with climate conditions led to erosion catastrophic flooding damage loss of biodiversity ...constraining rivers with levees and dams ... has increased vulnerability to natural disasters by degrading the buffering capacity of the natural system (eg. Mustafa 2007, Farber and Costanza et al. 1987, Haeuber & Michener 1998). ...today, approx. 90% of AZ and NM’s original riparian ecosystems have disappeared (NMDGF 2006, Krzysik 1990, Ohmart & Anderson 1986, Brinson et al. -

3-D Seismic Exploration for the Victorio Peak Treasure

3-D seismic exploration for the Victorio Peak treasure James Rector*, John Washboume, University of California at Berkeley; Alex Alonso, Ova Noss Family Partnership; Martin Cherrington, Cherrington Corporation; Tony Delonas, Ova Noss Family Partnership; and Rob Huggins, Geometries, Inc. Summary In January of 1994, we conducted an extensive seismic experiment to find caverns under Victorio Peak, a bioherm reef structure located approximately 80 miles northeast of Las Cruces, New Mexico. Within Victorio Peak there is reputed to be an extensive network of caverns, tunnels and fissures that contain a large and varied treasure consisting of gold bars, Spanish armor, jewels, coins, and human skeletons. We used an array of seismic sources that included a sledgehammer on the surface of the mountain, a sledgehammer impacting on the walls of two deep fissureswithin the mountain, as well as blasting caps located in boreholes drilled into the mountain. Approximately 2,000 source positions were recorded by 120 receiver channels consisting of geophones cemented into fissure walls and hydrophones deployed in a deep horizontal borehole drilled at the base of the mountain. The data analysis consisted of measuring reduced traveltime and amplitude of the direct arrival and isolating those source/receiver pairs that exhibited anomalously large direct arrival traveltimes and/or low amplitudes. We have currently identified and located amajor amplitude anomaly under the peak that will be drilled and explored during the summer of 1994. History of the Treasure and its Exploration For many years, the Victorio Peak Treasure has been the subject of Indian lore, books, articles, government documents and television documentaries (James, 1953, Kootklowski, 1966, Anonymous, 1973,). -

Hands Across History

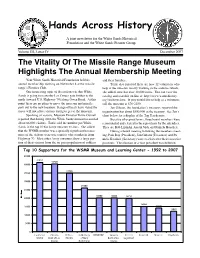

Hands Across History A joint newsletter for the White Sands Historical Foundation and the White Sands Pioneer Group. Volume III, Letter IV December 2007 The Vitality Of The Missile Range Museum Highlights The Annual Membership Meeting Your White Sands Historical Foundation held its and their families. annual membership meeting on November 8 at the missile Terrie also reported there are now 12 volunteers who range’s Frontier Club. help at the museum mostly working in the archives which, One interesting topic of discussion was that White she added, now has over 10,000 items. You can view the Sands is going to move the Las Cruces gate further to the catalog and search it on line at: http://www.wsmr-history. north (toward U.S. Highway 70) along Owen Road. At this org/Archives.htm. If you would like to help as a volunteer, point there are no plans to move the museum and missile call the museum at 678-2250. park out to the new location. Range officials have stated the Jon Gibson, the foundation’s treasurer, reported the move will not affect visitors trying to get to the museum. organization has about $350,000 in the treasury. See Jon’s Speaking of visitors, Museum Director Terrie Cornell chart below for a display of the Top Ten donors. reported that during 2006 the White Sands museum recorded Because of expired terms, three board members were about 66,000 visitors. Terrie said the number put White renominated and elected to their positions by the attendees. Sands in the top 10 for Army museum visitors. -

Shomaker June 2004

EVALUATION OF POTENTIAL WATER-RESOURCE IMPACTS FROM BLM PROPOSED RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN AMENDMENT FOR FEDERAL FLUID MINERALS LEASING AND DEVELOPMENT IN THE SALT BASIN, NEW MEXICO prepared by Steven T, Finch, Jr., CPG JOHN SHOMAKER & ASSOCIATES, INC. Water-Resource and Environmental Consultants Albuquerque, New Mexico 87107 prepared for Campaign to Protect America’s Lands and the Otero Mesa Coalition June, 2004 ™ JSAI ii CONTENTS page OVERVIEW……………...……………………………………………………………………iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 1.1 BLM Proposed Plan.......................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objective and Purpose....................................................................................... 2 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF REGIONAL AQUIFER(S)........................................................ 2 2.1 Structure and Framework................................................................................... 2 2.2 Geologic Units................................................................................................. 3 2.3 Recharge......................................................................................................... 6 2.4 Direction of Ground-Water Flow ........................................................................ 7 2.5 Current and Historic Use................................................................................... 8 2.6 Future Use...................................................................................................... -

Hands Across History

Hands Across History A joint newsletter for the White Sands Historical Foundation and the White Sands Pioneer Group. Volume IV, Letter IV November 2008 Annual Meeting Reveals Museum Growth At the annual Foundation members meeting on Nov. 6, He announced his new Trinity Site display is just three board members (Pam Vick, John Bayer and Jim Eckles) about ready to go on the museum floor. He also is planning were re-elected to the board of directors. Also Pam Vick an- on an exhibit to feature the Nike family of missiles. They nounced she would not seek another term as the Foundation are a pioneering trio of missiles and were very important to president. No one at the meeting volunteered to replace her. WSMR in its early days. Darren Court, WSMR Museum Director, reported visi- He wrapped up his report stating one major goal is to tation of the museum is still on the increase. During the last do more educational programs with children. year more than 40 school groups visited and in fiscal year Bob Lipinski followed with a “brick” report about the 2008 they recorded over 82,000 visitors to the building. He signature plaza between the V-2 building and Missile Park. thinks they will exceed 100,000 per year in the near future. He said since the Foundation started the program in 2003, His bad news was that the museum’s budget has been almost 500 bricks have been placed and brought in about cut along with most everyone else’s at White Sands. He $51,000. -

Progradational Slope Architecture and Sediment Partitioning in The

PROGRADATIONAL SLOPE ARCHITECTURE AND SEDIMENT PARTITIONING IN THE MIXED SILICICLASTIC-CARBONATE BONE SPRING FORMATION, PERMIAN BASIN, WEST TEXAS by Wylie Walker A thesis submitted to the Faculty and the Board of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geology). Golden, Colorado Date _______________________ Signed: _______________________________ Wylie T. Walker Signed: _______________________________ Dr. Zane Jobe Thesis Advisor Golden, Colorado Date _______________________ Signed: _______________________________ Dr. M. Stephen Enders Department Head Department of Geology and Geological Engineering ii ABSTRACT Slope-building processes and sediment partitioning in mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sediment routing systems are poorly understood but are important constraints on the spatial and temporal distribution of reservoir-forming elements. The Bone Spring Formation, Delaware Basin, west Texas is a mixed carbonate-siliciclastic system that consists of cyclic slope-to-basin hemipelagites, turbidites, and debrites that were sourced from the Victorio Peak Formation carbonate shelf margin and Bone Spring Formation slope during Leonardian time (~275 Ma). Much research has focused on the basinal deposits of the Bone Spring Fm., but there has been little research on the proximal, upper slope segment of the Bone Spring sediment routing system. In this study, we constrain the stratigraphic architecture of the Bone Spring Fm. that outcrops in Guadalupe Mountains National Park in order to delineate the slope clinothem geometry and the dynamics of carbonate and siliciclastic sediment delivery to the basin. We record the outcropping Bone Spring Fm. upper-slope as composed predominantly (~90% of the study area) of fine- grained carbonate hemipelagites and sediment gravity flows containing a high biogenic silica content (i.e. -

TERRITORIAL NEW MEXICO GENERAL STEPHEN H. KEARNY at the Outbreak of the Mexican War General Stephen H

TERRITORIAL NEW MEXICO GENERAL STEPHEN H. KEARNY At the outbreak of the Mexican War General Stephen H. Kearny was made commander of the Army of the West by President Polk and ordered to lead a 1700 man expeditionary force from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to occupy New Mexico and California. He quickly accomplished the bloodless conquest of New Mexico on 19 August 1846, ending the brief period of Mexican control over the territory. After spending a little more than a month in Santa Fe as military governor with headquarters in Santa Fe, Kearny decided to continue on to California after ensuring that a civilian government was in place. Early the following year in Kearny's absence New Mexicans mounted their only challenge to American control. In January, 1847, Kearny's appointed Governor, Thomas H. Benton and six others were murdered in Taos. Colonel Sterling Price moved immediately to quash the insurrection. Price led a modest force of 353 men along with four howitzers out of Albuquerque, adding to the size of his force as he marched north up the Rio Grande by absorbing smaller American units into his command. After a series of small engagements, reaching Taos Pueblo on 3 February Price found the insurgents dug in. Over the next two days Price's force shelled the town and surrounded it in an attempt to force surrender. When American artillery finally breached the walls of the, the battle quickly turned into a running fight with American forces chasing down their opponents who attempted to find shelter in the mountains. In all, perhaps as many as one hundred guerillas were killed, while Price suffered the loss of seven men killed and forty-five wounded. -

Overview of Fresh and Brackish Water Quality in New Mexico

NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES Overview of Fresh and Brackish Water Quality in New Mexico Lewis Land Open-file Report 583 June 2016 New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources A division of New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology Socorro, NM 87801 (575) 835 5490 Fax (575) 835 6333 geoinfo.nmt.edu Overview of Brackish Water Resources in New Mexico Lewis Land Open-file Report 583 June 2016 New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources PROJECT FUNDING New Mexico Environment Department, Drinking Water Bureau, MOU 16 667 3000 0006, Project 4. The views and conclusions are those of the authors, and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the State of New Mexico. NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES FRESH AND BRACKISH WATER QUALITY CONTENTS I. Introduction ....................................................................... 1 Figures 1. New Mexico counties, groundwater basins and aquifers, and tectonic regions ........................2–3 II. Methods .................................................................................. 3 2. San Luis Basin, surface geology and data distribution ......................................................... 8 I. Summary of Observations ................................... 5 3. San Luis Basin plots of TDS Variation of salinity as a function of depth ......... 5 and specific conductance vs. depth ........................... 9 Three-dimensional variations in 4. Española Basin, surface geology -

Geology and Oil and Gas Potential of the Northeast Otero Platform Area, New Mexico Bruce A

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/26 Geology and oil and gas potential of the northeast Otero platform area, New Mexico Bruce A. Black, 1975, pp. 323-333 in: Las Cruces Country, Seager, W. R.; Clemons, R. E.; Callender, J. F.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 26th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 376 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1975 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States.