Gardner Read: Symphony No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

An Interview with Robert Shaw: Reflections at Eighty

An Interview with Robert Shaw: Reflections at Eighty by Jeffrey Baxter RobertShaw .Robert Shaw's distinguished career began in New York City In 1979, Shaw was appointed by President Jimmy Carter to in 1938, where he prepared choruses for such renowned con the National Council on the Arts and he was a 1991 recipient of ductors as Fred Waring, Arturo Toscanini, and Bruno Walter. the Kennedy Center Honors, the nation's highest award given to In 1949 he formed the Robert Shaw Chorale, which for two artists. Musical America, the international directory of the per decades reigned as America's premier touring choir. Under the forming arts, named him Musician of the Year for 1992, and auspices ofthe U.S. State Department, the Chorale performed during the same year he was awarded the National Medal ofthe in thirty countries throughout Europe, the Soviet Union, the Arts in a White House ceremony. He was the 1993 recipient of Middle East, and Latin America. During this period Shaw also the Conductors' Guild TheodoreThomas Award, in recognition served as Music Director ofthe San Diego Symphony and then ofhis outstanding achievement in conducting and his contribu as Associate Conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, working tions to the education and training ofyoung conductors. closely with George Szell for eleven years. He served as Music A regular guest conductor ofmajor orchestras in this country Director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra from 1967 to and abroad, Shaw also is in demand as a teacher and lecturer at 1988, during which time the orchestra garnered widespread leading U.S. -

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 P.M. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 p.m. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East.Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East. Celebrating the New Year with music is nothing new for Maazel: he holds the modern record for most appearances as conductor of the celebrated New Year’s Day concerts in Vienna by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. There, of course, the fare is made up mostly of music by the waltzing Johann Strauss family, father and sons. For his New Year’s Eve concert with the New York Philharmonic Maazel has chosen quintessentially American music by the composer considered by many to be America’s closest equivalent to the Strausses, George Gershwin. -

178 Chapter 6 the Closing of the Kroll: Weimar

Chapter 6 The Closing of the Kroll: Weimar Culture and the Depression The last chapter discussed the Kroll Opera's success, particularly in the 1930-31 season, in fulfilling its mission as a Volksoper. While the opera was consolidating its aesthetic identity, a dire economic situation dictated the closing of opera houses and theaters all over Germany. The perennial question of whether Berlin could afford to maintain three opera houses on a regular basis was again in the air. The Kroll fell victim to the state's desire to save money. While the closing was not a logical choice, it did have economic grounds. This chapter will explore the circumstances of the opera's demise and challenge the myth that it was a victim of the political right. The last chapter pointed out that the response of right-wing critics to the Kroll was multifaceted. Accusations of "cultural Bolshevism" often alternated with serious appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of any given production. The right took issue with the Kroll's claim to represent the nation - hence, when the opera tackled works by Wagner and Beethoven, these efforts were more harshly criticized because they were perceived as irreverent. The scorn of the right for the Kroll's efforts was far less evident when it did not attempt to tackle works crucial to the German cultural heritage. Nonetheless, political opposition did exist, and it was sometimes expressed in extremely crude forms. The 1930 "Funeral Song of the Berlin Kroll Opera", printed in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, may serve as a case in point. -

By MARTIN BOOKSPAN

December 31, 2007, 8:00pm on PBS New York Philharmonic New Year’s Eve Gala with Joshua Bell In September Live From Lincoln Center observed one of its longtime traditions: the Gala opening concert of the new season of the New York Philharmonic. On December 31 we'll re-invent another longtime Live From Lincoln Center tradition: the Gala New Year's Eve concert by the New York Philharmonic. Music Director Lorin Maazel will be on the podium for a program of music appropriate for the festive occasion, and the guest artist will be the acclaimed violinist, Joshua Bell. I first encountered Joshua Bell at the Spoleto Festival, U.S.A. in Charleston, South Carolina. He was then barely into his teens but he was already a formidable violinist, playing chamber music with some of the world's most honored musicians. Not long afterward he burst upon the international scene at what was described as "a sensational debut" with the Philadelphia Orchestra and its Music Director of the time, Riccardo Muti. Joshua Bell was brought up in Bloomington, Indiana, where his father was a Professor at Indiana University. I.U., as it is known in academia, is an extraordinary university, with a School of Music that is world-renowned. Among its outstanding faculty was the eminent violinist Josef Gingold, who became Josh's inspired (and inspiring) mentor and devoted friend. Indeed it was the presence of Gingold in Indiana that led to the establishment of the Indianapolis International Violin Competition. One way for a young musician to attract attention is to win one of the major international competitions. -

TURANDOT Cast Biographies

TURANDOT Cast Biographies Soprano Martina Serafin (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Marshallin in Der Rosenkavalier in 2007. Born in Vienna, she studied at the Vienna Conservatory and between 1995 and 2000 she was a member of the ensemble at Graz Opera. Guest appearances soon led her to the world´s premier opera stages, including at the Vienna State Opera where she has been a regular performer since 2005. Serafin´s repertoire includes the role of Lisa in Pique Dame, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth, Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, and Donna Elvira in Don Giovanni. Upcoming engagements include Elsa von Brabant in Lohengrin at the Opéra National de Paris and Abigaille in Nabucco at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. Dramatic soprano Nina Stemme (Turandot) made her San Francisco Opera debut in 2004 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, and has since returned to the Company in acclaimed performances as Brünnhilde in 2010’s Die Walküre and in 2011’s Ring cycle. Since her 1989 professional debut as Cherubino in Cortona, Italy, Stemme’s repertoire has included Rosalinde in Die Fledermaus, Mimi in La Bohème, Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the title role of Manon Lescaut, Tatiana in Eugene Onegin, the title role of Suor Angelica, Euridice in Orfeo ed Euridice, Katerina in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro, Marguerite in Faust, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Marie in Wozzeck, the title role of Jenůfa, Eva in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Elsa in Lohengrin, Amelia in Un Ballo in Machera, Leonora in La Forza del Destino, and the title role of Aida. -

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Gustav Mahler Born July 7, 1860, Kalischt, Bohemia. Died May 18, 1911, Vienna, Austria. Symphony No. 9 in D Major Mahler began his ninth symphony in the spring of 1909 and on April 1, 1910, he told the conductor Bruno Walter that the score was complete. Walter conducted the first performance with the Vienna Philharmonic on June 26, 1912. The score calls for four flute s and piccolo, four oboes and english horn, three clarinets, E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, four bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, bass drum, tam -tam, triangle, glockenspiel, chimes, two harps, and strings. Performance time is approximately eighty -one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony were given at Orchestra Hall on April 6 and 7, 1950, with George Szell conductin g. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on November 30, December 1, 2, and 5, 1995, with Pierre Boulez conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on August 11, 1979, with Lawrence Foster conducti ng, and most recently on June 28, 1991, with James Levine conducting. Because this symphony is Mahler’s last completed work, and because he died tragically of heart disease at the age of fifty shortly after finishing it, leaving behind his beautiful wife Alma and young daughter Anna, it’s often considered both his farewell and his most deeply personal score. Bruno Walter, who conducted the premiere thirteen months after Mahler’s death, said that he recognized the composer’s own gait in the limping rhythm o f the march at the climax of the first movement. -

MUSIC DIRECTORS 100 Years Of

TABLE OF CONTENTS “A Hero’s Journey: Fun & Games .......................6 Beethoven & Prometheus, Grades 4-8 . 2 Fan Mail ...........................7 Civil Rights: Remembering Youth Orchestra ....................8 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Grades 6-12 . 3 Children’s Chorus ...................8 See the Sounds. 4 Youth Chorus. .8 Conductor of the Orchestra ............5 Family Concerts ....................8 2017-18 Season Guide for Young Concert-goers MUSIC DIRECTORS 100 Years of NIKOLAI SOKOLOFF 1918-33 The Cleveland Orchestra!! 2017-2018 marks the 100th season of The Cleveland and dismissal pro cess (where every bus and corresponding Orchestra! You may not realize that by coming to school group gets a number) was established in 2000 to a Cleveland Orchestra Education Concert you are man age traffic and insure students’ safety. There are many part of a great Cleveland tradition! Students have more cars on the road today than there ARTUR RODZINSKI were in the 1930’s! 1933-43 been attending Cleveland Orchestra concerts since 1918! Ms. Lillian Bald win, the Orchestra’s first Ed u ca tion Director, pioneered the In the be gin ning, The Cleve land Or ches tra performed format of ‘educational concerts’ we concerts in com mu ni ty cen ters and sev er al area schools, know today. She developed extensive including East Tech and West Tech High Schools in study ma te rials so students could be Cleveland, Shaw High School in East Cleveland, and knowl edge able about the music they Lakewood High School. By 1920 audienc es be came too would hear at the concerts. (Instead large to accommodate in school settings and teachers and of read ing The Score as you are now, students be gan to trav el to hear The Cleve land Orchestra, ERICH LEINSDORF students read Ms. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1976

I M' n, v ~# ^ »>'* •«*^ ^T* > ^'^.._, KlLBu**%m*lJcML^teff-'il Btf^^flB IS^.'^I For 104 years we've been serious about people who make music. In 1872 Boston University established the first professional music program within an American university to train creative and talented students for careers in music. 104 years later the Boston University School of Music is still doing what it does best. • Performance • Music Education • History and Literature • Theory and Composition strings music history and literature Walter Eisenberg, violin Charles Kavaloski, French horn Karol Berger ' Gerald Gelbloom, violin Charles A. Lewis, Jr., trumpet Murray Lefkowitz Bernard Kadinoff, viola David Ohanian, French horn Joel Sheveloff Endel Kalam, chamber music Samuel Pilafian, tuba theory and composition ' Robert Karol, viola Rolf Smedvig, trumpet David Carney ' Alfred Krips, violin ' Harry Shapiro, French horn David Del Tredici 'Eugene Lehner, chamber music ' Roger Voisin, trumpet John Goodman 'Leslie Martin, string bass ' Charles Yancich, French horn Alan MacMillan George Neikrug, cello percussion Joyce Mekeel ' Mischa Nieland, cello * Thomas Ganger Malloy Miller Leslie Parnas, cello ' Charles Smith Gardner Read 'Henry Portnoi, string bass Allen Schindler 'Jerome Rosen, violin harp Tison Street Kenneth Sarch, violin Lucile Lawrence " Alfred Schneider, violin music education * Roger Shermont, violin piano Lee Chrisman 'Joseph Silverstein, violin Maria Clodes Allen Lannom Roman Totenberg, violin Anthony di Bonaventura Jack O. Lemons Walter Trampler, viola -

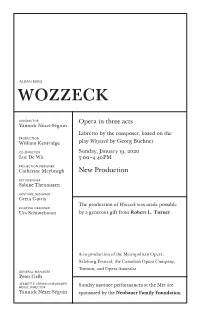

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

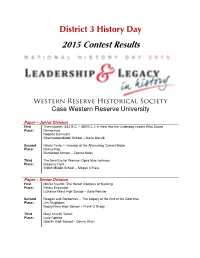

2015 Contest Results

District 3 History Day 2015 Contest Results Western Reserve Historical Society Case Western Reserve University Paper – Junior Division First Themistocles (524 B.C. – 459 B.C.): A View Into the Underdog Leader Who Saved Place: Democracy Roberto Demarchi Beachwood Middle School – Maria Marsilli Second Nikola Tesla — Inventor of the Alternating Current Motor Place: Rishav Roy Birchwood School -- Connie Miller Third The New Era for Woman: Opha Mae Johnson Place: Breanna Trent Shiloh Middle School -- Megan O'Hara Paper – Senior Division First Minnie Vautrin: The Heroic Goddess of Nanking Place: Felicia Escandon Lutheran West High School – Dave Ressler Second Reagan and Gorbachev -- The Legacy of the End of the Cold War Place: Jim Fitzgibbon Rocky River High School – Frank O’Grady Third Mary Church Terrell Place: Lucy Cipinko Oberlin High School – Donna Shurr Website – Junior Individual Division First John D. Rockefeller : Industrial & Philanthropic Leader Place: J. Victor Pan Birchwood School – Connie Miller Second Florence Nightingale : A Legacy of Innovative Medical Care Place: Farah Sayed Birchwood School – Connie Miller Third Lewis Hine : Taking the Lead to Expose the Dangers of Child Labor Place: Zuha Jaffar Birchwood School – Connie Miller Website – Senior Individual Division First Rabbi Arthur J. Lelyveld : "A Man Obsessed with Peace" Place: Jeremy Gimbel Shaker Heights High School – Tim Mitchell Second Why We Live Apart : Institutionalized Segregation in the 20th Century Place: Joe Berusch Shaker Heights High School – Tim Mitchell Third Signs of the Times: Manualism Versus Oralism in Deaf Education Place: Nadia Degeorgia Shaker Heights High School – Tim Mitchell Website – Junior Group Division First The House That George Built Place: Ryan Stimson, Matteo Giovanetti, Marc Giovanetti Saint Barnabas School – Judith Darus Second More Than Just the Bomb : J. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23" black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. Order Number 8717594 The future of the symphony orchestra based upon its historical development Winteregg, Steven Lee, D.M .A. The Ohio State University, 1987 UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, M I 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. Problems encountered with this document have been identified here with a check mark V .