The Broadcasting Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CUFBRT404A Coordinate Outside Broadcasts

CUFBRT404A Coordinate outside broadcasts Revision Number: 1 CUFBRT404A Coordinate outside broadcasts Date this document was generated: 27 May 2012 CUFBRT404A Coordinate outside broadcasts Modification History Not applicable. Unit Descriptor Unit descriptor This unit describes the performance outcomes, skills and knowledge required to coordinate outside broadcasts in the media industries. No licensing, legislative, regulatory or certification requirements apply to this unit at the time of endorsement. Application of the Unit Application of the unit Broadcast technicians or technologists apply the skills and knowledge described in this unit. Although they work under the direction of a broadcast engineer or technical director, they are expected to work with minimum supervision and, in the context of outside broadcasts, would usually be responsible for supervising others. The person coordinating outside broadcast technical operations requires a broad range of technical skills associated with setting up and monitoring live feeds, as well as the flexibility to rectify faults quickly and efficiently. They also need to understand the requirements of others involved in the production chain. Note: To meet the requirements of this unit, candidates need to demonstrate competency in the coordination of outside broadcasts for either television or radio. The Required Skills and Knowledge section should be tailored accordingly. Approved Page 2 of 13 © Commonwealth of Australia, 2012 Innovation and Business Skills Australia CUFBRT404A Coordinate outside broadcasts Date this document was generated: 27 May 2012 Licensing/Regulatory Information Not applicable. Pre-Requisites Prerequisite units Employability Skills Information Employability skills This unit contains employability skills. Elements and Performance Criteria Pre-Content Elements describe the Performance criteria describe the performance needed to essential outcomes of a demonstrate achievement of the element. -

MEDIA ENGAGEMENTS for the VICE-CHANCELLOR 1. Completed

MEDIA ENGAGEMENTS FOR THE VICE-CHANCELLOR 1. Completed Interviews Interviews profiling Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng or focusing on her appointment, her role, her vision, etc (and not news-based interviews) Media House Date Interview Link SABC 3 Leading 24 December http://peararchive3.co.za/SynopsisClip/2019-01-21/16547031B0A.html Citizen http://peararchive3.co.za/SynopsisClip/2019-01-21/16548281874.html Radio 702 20 December https://omny.fm/shows/afternoon-drive-702/uct-vc-pays-off-student-debt/embed/ http://www.702.co.za/articles/331518/we-should-focus-on-the-kind-of-values-we-inculcate-in-students eNCA 19 December http://peararchive3.co.za/SynopsisClip/2018-12-19/1634206.mp4 http://peararchive3.co.za/SynopsisClip/2018-12-19/1634207.mp4 http://peararchive3.co.za/SynopsisClip/2018-12-19/1634208.mp4 Future Leadership 10 December https://soundcloud.com/user-883320365/the-future-of-leadership-interview-with-prof-mamokgethi-phakeng Forum https://vimeo.com/304323302 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O79slUPyuaQ Sunday Independent 9 December http://www.peararchive2.co.za/media/Print/167924E9FA9.jpg / Weekend Argus http://www.peararchive2.co.za/media/Print/167924165F0.jpg University World 7 December http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20181204112042716 News Science Stars 4 December https://twitter.com/FabAcademic/status/1069952116523974656 https://twitter.com/FabAcademic/status/1069953275754098688 https://twitter.com/FabAcademic/status/1069953379697340416 https://twitter.com/FabAcademic/status/1069954202393346048 https://twitter.com/FabAcademic/status/1069955253011927040 -

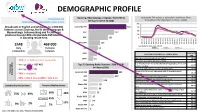

Jacaranda Fm in Essence

DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE Gauteng, Mpumalanga, Limpopo, North West Jacaranda FM enjoys a consistent audience flow JACARANDA FM Afrikaans LSM 8-10 (000) throughout the day (Mon to Sun) – (000) PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS (Part 1 of 2) 200 Broadcasts in English and Afrikaans to 1 004 000 Jacaranda FM 366 150 listeners across Gauteng, North West, Limpopo & 100 Mpumalanga. Johannesburg and Pretoria are 947 247 pivotal areas and 84% of Jacaranda FM listeners 50 in Gauteng reside here. RSG 185 0 Metro FM 109 0100-0200 0200-0300 0300-0400 0400-0500 0500-0600 0600-0700 0700-0800 0800-0900 0900-1000 1000-1100 1100-1200 1200-1300 1300-1400 1600-1700 1700-1800 1800-1900 1900-2000 2100-2200 2300-2400 0000-0100 1400-1500 1500-1600 2000-2100 2200-2300 1h48 469 000 Ave Qhr by hr, Mon – Sun, ADULTS Daily Exclusive 702 88 M-F SAT SUN Listenership Listeners Jacaranda 5FM 80 LIFESTYLE STATEMENTS - AGREE WITH FM OFM 44 I am very conscious about my health 48.8% • 47% of individuals listen exclusively I consider my diet to be very healthy 43.4% It is important for me to include lots of vegetables, fruit and • Average HHI of R27 482 Top 10 Gauteng Radio Stations : SEM 8-10 & 63.4% salad in my diet Afrikaans (000) • Average age of 41 You can judge a person by the car they drive 44.0% Jacaranda FM 297 My car should be well equipped with all possible safety Exclusive 52.5% • 70% is employed features Listenership 947 257 My car should express my personality 48.8% • 63% in LSM 8-10 and 60% in SEM 9-10 Comfort is the most important thing in a car 51.6% RSG 138 I love to buy new gadgets and appliances 46.9% Metro FM 95 I do extensive research before purchasing an electronic Listenership by location Listenership by device 44.4% item. -

Who Owns the News Media?

RESEARCH REPORT July 2016 WHO OWNS THE NEWS MEDIA? A study of the shareholding of South Africa’s major media companies ANALYSTS: Stuart Theobald, CFA Colin Anthony PhibionMakuwerere, CFA www.intellidex.co.za Who Owns the News Media ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We approached all of the major media companies in South Africa for assistance with information about their ownership. Many responded, and we are extremely grateful for their efforts. We also consulted with several academics regarding previous studies and are grateful to Tawana Kupe at Wits University for guidance in this regard. Finally, we are grateful to Times Media Group who provided a small budget to support the research time necessary for this project. The findings and conclusions of this project are entirely those of Intellidex. COPYRIGHT © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd This report is the intellectual property of Intellidex, but may be freely distributed and reproduced in this format without requiring permission from Intellidex. DISCLAIMER This report is based on analysis of public documents including annual reports, shareholder registers and media reports. It is also based on direct communication with the relevant companies. Intellidex believes that these sources are reliable, but makes no warranty whatsoever as to the accuracy of the data and cannot be held responsible for reliance on this data. DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS Intellidex has, or seeks to have, business relationships with the companies covered in this report. In particular, in the past year, Intellidex has undertaken work and received payment from, Times Media Group, Independent Newspapers, and Moneyweb. 2 www.intellidex.co.za © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd Who Owns the News Media CONTENTS 1. -

Dynamics of Competition in Two-Sided Markets with Differentiated Products: a Case Study of the Radio Industry Following the Primedia/New Africa Investment Ltd Merger

Work in progress, not for citation purposes Dynamics of competition in two-sided markets with differentiated products: A case study of the radio industry following the Primedia/New Africa Investment Ltd merger Rantao Itumeleng1 Abstract The decision by the Competition Tribunal to unconditionally approve the Primedia/New Africa Investment Limited merger case (NAIL) is the subject of this paper. This study conducts an impact assessment of the Primedia/NAIL case. It does so using market definition as the first step in the assessment of competition in the Gauteng commercial radio industry. In markets with two different groups of customers, repositioning is fundamental in the assessment of anticompetitive effects post-merger. Utilizing tools identified in literature and international cases, the study adopts an ex post approach to assess competition in the Gauteng commercial radio industry. Findings indicate that in mergers that do not lead to join control, merging firms’ stations reposition away. Highveld and Kaya repositioned away from each other post-merger. Because of this dynamic nature of radio as well as the structure of the market in Gauteng, no effective competitors to Kaya and Highveld in the relevant market, Highveld and Kaya’s prices rose faster than other radio stations’ prices post-merger. At an industry level, competition also deteriorated post-merger as prices rose significantly mainly because of few sales house. These findings imply that the initial decision by the Competition Tribunal to approve the merger unconditionally may be incorrect. Keywords: Unilateral effects, coordinated effects, Repositioning, Partial acquisition 1. Introduction Prior to 1978, radio was the leading electronic medium in South Africa before being surpassed by television (Competition Commission, 2006:1). -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: Worlddmb Global Update Digital Radio Broadcasting Using the DAB Family of Standards Global Overview Digital

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: WorldDMB Global Update Digital radio broadcasting using the DAB family of standards Global overview Digital radio is making significant advances across Europe with national services now firmly established in the UK, Norway, Switzerland, Denmark, Germany and Netherlands – all with coverage levels of over 90%. Recent months have seen several important developments for DAB digital radio: Norway will switch off FM in 2017 Switzerland has announced its plans for DSO (Digital Switchover) between 2020 and 2024 In Germany, following public broadcaster ARD’s long term commitment to DAB+ in November 2014, the Ministry for Transport and Digital Infrastructure has made clear its strong support and has established a new cross-industry Steering Board to drive forward the adoption of digital radio The UK has launched a major programme to build out national and local DAB coverage, and the licence for a second national commercial multiplex has been awarded, with up to 15 new stations on air in early 2016. Denmark has issued a clear roadmap for digital radio, with a transition to DAB+ by end 2016 and a decision on DSO when 50% of listening is digital The Netherlands has seen the launch (Sept 2013) and strong marketing of national DAB+ services. The next phase of development takes place in 2015 with the launch of regional services. In Italy, in March the regulator AgCom issued licences in three new regions; the coverage of national services is being extended in the South of Italy and Sicily and a plan of frequencies for local digital radio in 40 new regions has been published and AgCom will most likely publish the rules to extend DAB+ services in the new local areas by this summer. -

Employment Equity Act (55/1998): 2019 Employment Equity Public Register in Terms of Section 41 43528 PUBLIC REGISTER NOTICE

STAATSKOERANT, 17 JULIE 2020 No. 43528 31 Employment and Labour, Department of/ Indiensneming en Arbeid, Departement van DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT AND LABOUR NO. 779 17 JULY 2020 779 Employment Equity Act (55/1998): 2019 Employment Equity Public Register in terms of Section 41 43528 PUBLIC REGISTER NOTICE EMPLOYMENT EQUITY ACT, 1998 (ACT NO. 55 OF 1998) I, Thembelani Thulas Nxesi, Minister of Employment and Labour, publish in the attached Schedule hereto, the register maintained in terms of Section 41 of the Employment Equity Act, 1998 (Act No. 55 of 1998) of designated employers that have submitted employment equity reports in terms of Section 21, of the Employment Equity Act, Act No. 55 of 1998 as amended. MR.lWNXESI, MP MINISTER OF EMPLOYMENT AND LABOUR ')..,6j oZ> do:2,"eJ 1/ ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ISAZISO SEREJISTA YOLUNTU UMTHETHO WOKULUNGELELANISA INGQESHO, (UMTHETHO YINOMBOLO YAMA-55 KA-1998) Mna, Thembelani Thulas Nxesi, uMphathiswa wezengqesho kanye nezabasebenzi, ndipapasha kule Shedyuli iqhakamshelwe apha, irejista egcina ngokwemiqathango yeCandelo 41 lomThetho wokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho, ka- 1998 (umThetho oyiNombolo yama-55 ka-1998) izikhundla zabaqeshi abangenise iingxelo zokuLungelelanisa iNgqesho ngokwemigaqo yeCandelo 21, lo mThetho wokulungelelanisa iNgqesho, umThetho oyiNombolo yama-55 ka- 1998. -6'';7MR.TW NXESI, MP UMPHATHISWA WEZENGQESHO KANYE NEZABASEBENZI 26/tJ :20;:J,()1/ This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 32 No. 43528 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 17 JULY 2020 List of designated employers who reported for the 1 September 2019 reporting cycle Description of terms: No: This represents sequential numbering of designated employers & bears no relation to an employer. (The list consists of 5969 large employers & 21158 small employers). -

Mtn Radio Awards 2010 - Winners

MTN RADIO AWARDS 2010 - WINNERS BEST MUSIC SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST The Saturday Surgery 5FM - SABC Broadcasting BEST MUSIC SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST Georgie in the Afternoon Kaya Fm Radio - Kagiso Media BEST BREAKFAST SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST Just Plain Breakfast Jacaranda Fm - Kagiso Media BEST BREAKFAST SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST Good Morning Gauteng Kaya Fm Radio - Kagiso Media BEST DAY TIME SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST The David O'Sullivan Show Talk Radio 702 - Primedia Broadcasting BEST DAY TIME SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST The Redi Direko Show Talk Radio 702 - Primedia Broadcasting BEST NIGHT TIME SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST Home with Thabiso Sikwane Kaya Fm Radio - Kagiso Media BEST NEWS SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST Today with John Perlman Kaya Fm Radio - Kagiso Media BEST NEWS SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST Capricorn Talk with Thabiso Kotane Capricorn FM BEST SPORTS SHOW OF THE YEAR FINALIST The Sportscage East Coast Radio - Kagisto Media BEST MUSIC PRESENTER OF THE YEAR FINALIST Barney Simon Classic Rock Show Jacaranda Fm - Kagiso Media BEST MUSIC PRESENTER OF THE YEAR FINALIST Dewald Noel Saturday Night Fever Jacaranda Fm - Kagiso Media BEST MUSIC PRESENTER OF THE YEAR FINALIST Catherine Grenfell Live to the power of 5 5FM - SABC Broadcasting BEST BREAKFAST SHOW PRESENTER OF THE YEAR FINALIST Gareth Cliff 5FM Mornings with Gareth Cliff 5FM - SABC Broadcasting BEST BREAKFAST SHOW PRESENTER OF THE YEAR FINALIST John Robbie The John Robbie Show Talk Radio 702 - Primedia Broadcasting BEST DAY TIME PRESENTER OF THE YEAR FINALIST Jenny Crwys-Williams -

World-Class Infrastructure Which Enables Citizens to Connect to High

Connectivity World-class infrastructure which enables citizens to connect to high-speed internet. 1 About SENTECH SENTECH is all about connecting you to the world and connecting the world to you. SENTECH SOC Limited is a State-Owned Company operating in the ICT sector. SENTECH offers digital content delivery services to Public and Commercial entities. In keeping abreast with rapid changes in the information and cyber physical society, SENTECH’s product and service offering has expanded to include SENTECH CONNECT which is Connectivity tailored for all sectors in rural and underserviced areas. 2 Connectivity Connectivity Technology SENTECH CONNECT provides high speed broadband access, always Broadband Access Network on Internet connection for government facilities in hard-to-reach areas in South Africa with a IP Core/Edge Networks minimum speed of 10Mbps scalable to 100Mbps. The network enables data, voice, video IP/MPLS Networks and other multimedia applications for any device, any network, anywhere and for Data Centre Solutions any business use. Our team designs networks and implements state-of- the-art fully integrated Transmission/Backhaul Solutions solutions for the following broadband access technologies: 3 Connectivity Technology SENTECH CONNECT offers five services, namely: 1. Broadband Access Networks 5G Features: SENTECH CONNECT provides high speed broadband access, • Supports voice, video calling, data and other multi-media always on Internet connection for government facilities in the communications, underserviced areas with a minimum speed of 10mbps scalable • Higher voice service quality compared to 4G services, to 100mbps. The network enables data, voice, video and other • Provide download speeds of 14.4 megabits per second and multimedia applications for business use. -

The Art of Pitching (2005) the Art of Co-Production the Art of Sourcing Content National and International Annual Observances Thought Memory

Producer Guide The PArti tofc hing Pitching A Handbook for Independent Producers 2013 Revised and Updated Published by the SABC Ltd as a service to the broadcast sector Pitch the act of presenting a proposal to a broadcaster – either in person or in the form of a document The word “pitch” became common practice in the early days of cinema when studios needed an expression of the passion that was not always evident in written words. “You write the words, but you pitch the feelings.” "If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together" - African proverb “A tree is known by its fruit” - Zulu proverb Content is Queen In this series The Art of Pitching (2005) The Art of Co-production The Art of Sourcing Content National and International Annual Observances Thought Memory © SABC Ltd 2013 Pitching The Art of PitchingPitching Revised Edition 2013 By Howard Thomas Commissioned by SABC Innovation and Editorial Conceptualised and initiated by Yvonne Kgame © SABC Ltd 2013 The Art of Pitching Howard Thomas has worked in the entertainment industry all his life, and in television since it first arrived in South Africa in 1976. He is an award-winning TV producer, and has worked in theatre, radio, films, magazines and digital media. He has been writing about the industry for over 20 years. He is also a respected trainer, lecturer and facilitator, columnist and SAQA accredited as an assessor and moderator. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by electrical or mechanical means, including any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. -

SABC July/August 2021 Packages in Celebration of Mandela Month XK FM 26 Breakfast Sports Show - 4 Weeks 26

SABC July/August 2021 Packages In Celebration of Mandela Month XK FM 26 Breakfast Sports Show - 4 Weeks 26 MOTSWEDING FM 27 Covid-19 Update 27 Family Health 28 Auto Feature 29 Legal, Finance & Consumer 30 contentsSABC 1 4 Movies SABC 1- Friday July @ 21h00 4 LESEDI FM 31 Movies SABC 1- Saturday July @ 20h00 5 Business Tuesdays 31 Movies SABC 1- Sunday July @ 21h00 6 Healthy Lifestyle 32 SABC 1 SHOWS - 18h00 Block 7 Diy 33 SABC 1 SHOWS - 19h30 Block 8 Transport News 34 Monthly Package 18h00-19h30 Squeeze-back and Commercial 9 Monthly Package 18h00-19h30 Squeeze-back and Commercial 10 IKWEKWEZI FM 35 Monthly Package 19h30 Tops and tails 11 National Savings Month - 4 Weeks 35 Monthly Package 18h00-19h30 Tops and tails 12 Umma Wamambala – Woman Crush Wednesday - 13 Weeks 36 Standard Terms and Conditions 13 LIGWALAGWALA FM 37 National Savings Month - 4 Weeks 37 PHALAPHALA FM 15 Business101 - 13 Weeks 38 Uplifting Vhembe Villages/Midi Na Midanani - 5 Weeks 15 Ariphalalane/Let’s Rescue Each Other - 4 Weeks 16 RADIO 2000 39 The Glenzito Super Drive 39 THOBELA FM 17 Re Go Thusha Ka Eng” / How Can We Help You - 5 Weeks 17 SAFM 40 I Am Leader (Ke Moetapele) - 5 Weeks 18 Life Happens 40 Fighting Covid With Prayer (Re Lwantšha Covid Ka Thapelo) - 4 Weeks 19 METRO FM 41 The Metro Fm Top 40 - 8 Weeks 41 MUNGHANA LONENE FM 20 Uplifting Small Local Businesses / Pfuka Uti Endlela - 5 Weeks 20 UKHOZI FM 42 Women In Business / A Hi Tshami Hi Mavoko - 4 Weeks 21 Sigiya Ngengoma - 8 Weeks 42 Round Table Discussion On Gbv With Stakeholders/Survivors 22 Round Table Discussion On Gbv With Stakeholders/Survivors 23 TRU FM 43 Mandela’s Memorable Moments 24 Trufm Top 30 - 8 Weeks 43 RSG 25 Standard Terms and Conditions 44 Praatsaam - 1 Week 25 Intro The month of July is celebrated worldwide and in South Africa as Nelson Mandela Month. -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto