The Philippines and ASEAN- Building Synergies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lao PDR's Way Into the ASEAN Single Market

Lao PDR’s Way into the ASEAN Single Market The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) ‘AEC 2015’ – what does it mean? Towards the ASEAN Community: ASEAN has been founded in The year 2015 marks the formal establishment of the AEC. 1967, the ASEAN Free Trade Area has been established in 1992 ‘Launching the AEC’ is a major milestone that will allow ASEAN and Lao PDR became a member in 1997. The ASEAN integration to foster a common identity and create momentum for further process intensified since 2003: at the 9th ASEAN Summit, ASEAN economic integration, relying on strong regional frameworks. Member States (AMS) decided to establish the ASEAN communi- Declaring the AEC operational, however, is not the final culmina- ty, which includes the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), the tion of the ASEAN economic integration process: ASEAN integra- ASEAN Political-Security Community (ASPSC), and the ASEAN tion is an on-going, dynamic process that will continue beyond Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC). 2015, as emphasized in the new AEC Blueprint 2025. The ASEAN Economic Community (AEC): The AEC will be estab- Progress and Achievements in the Implemen- lished in 2015. The ASEAN Leaders adopted the AEC Blueprint at tation of the AEC the 13th ASEAN Summit in 2007 in Singapore, to serve as a coher- ent master plan guiding the establishment of the AEC. The AEC ASEAN has endorsed 3 main agreements in order to create the Blueprint 2015 envisions four pillars for economic integration: Single Market: the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA) in 2010, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) in 1. -

Reflections on Agoncilloʼs the Revolt of the Masses and the Politics of History

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 3, December 2011 Reflections on Agoncilloʼs The Revolt of the Masses and the Politics of History Reynaldo C. ILETO* Abstract Teodoro Agoncilloʼs classic work on Andres Bonifacio and the Katipunan revolt of 1896 is framed by the tumultuous events of the 1940s such as the Japanese occupation, nominal independence in 1943, Liberation, independence from the United States, and the onset of the Cold War. Was independence in 1946 really a culmination of the revolution of 1896? Was the revolution spearheaded by the Communist-led Huk movement legitimate? Agoncilloʼs book was written in 1947 in order to hook the present onto the past. The 1890s themes of exploitation and betrayal by the propertied class, the rise of a plebeian leader, and the revolt of the masses against Spain, are implicitly being played out in the late 1940s. The politics of hooking the present onto past events and heroic figures led to the prize-winning manuscriptʼs suppression from 1948 to 1955. Finally seeing print in 1956, it provided a novel and timely reading of Bonifacio at a time when Rizalʼs legacy was being debated in the Senate and as the Church hierarchy, priests, intellectuals, students, and even general public were getting caught up in heated controversies over national heroes. The circumstances of how Agoncilloʼs work came to the attention of the author in the 1960s are also discussed. Keywords: Philippine Revolution, Andres Bonifacio, Katipunan society, Cold War, Japanese occupation, Huk rebellion, Teodoro Agoncillo, Oliver Wolters Teodoro Agoncilloʼs The Revolt of the Masses: The Story of Bonifacio and the Katipunan is one of the most influential books on Philippine history. -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

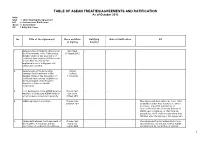

Table of Asean Treaties/Agreements And

TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. Title of the Agreement Place and Date Ratifying Date of Ratification EIF of Signing Country 1. Memorandum of Understanding among Siem Reap - - - the Governments of the Participating 29 August 2012 Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on the Second Pilot Project for the Implementation of a Regional Self- Certification System 2. Memorandum of Understanding Phuket - - - between the Government of the Thailand Member States of the Association of 6 July 2012 Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Health Cooperation 3. Joint Declaration of the ASEAN Defence Phnom Penh - - - Ministers on Enhancing ASEAN Unity for Cambodia a Harmonised and Secure Community 29 May 2012 4. ASEAN Agreement on Custom Phnom Penh - - - This Agreement shall enter into force, after 30 March 2012 all Member States have notified or, where necessary, deposited instruments of ratifications with the Secretary General of ASEAN upon completion of their internal procedures, which shall not take more than 180 days after the signing of this Agreement 5. Agreement between the Government of Phnom Penh - - - The Agreement has not entered into force the Republic of Indonesia and the Cambodia since Indonesia has not yet notified ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2 April 2012 Secretariat of its completion of internal 1 TABLE OF ASEAN TREATIES/AGREEMENTS AND RATIFICATION As of October 2012 Note: USA = Upon Signing the Agreement IoR = Instrument of Ratification Govts = Government EIF = Entry Into Force No. -

Asean Charter

THE ASEAN CHARTER THE ASEAN CHARTER Association of Southeast Asian Nations The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. =or inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 =ax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail: [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears on-line at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data The ASEAN Charter Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, January 2008 ii, 54p, 10.5 x 15 cm. 341.3759 1. ASEAN - Organisation 2. ASEAN - Treaties - Charter ISBN 978-979-3496-62-7 =irst published: December 2007 1st Reprint: January 2008 Printed in Indonesia The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgment. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2008 All rights reserved CHARTER O THE ASSOCIATION O SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS PREAMBLE WE, THE PEOPLES of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), as represented by the Heads of State or Government of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao Peoples Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Republic of the Philippines, the Republic of Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam: NOTING -

Australia and the Origins of ASEAN (1967–1975)

1 Australia and the origins of ASEAN (1967–1975) The origins of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and of Australia’s relations with it are bound up in the period of the Cold War in East Asia from the late 1940s, and the serious internal and inter-state conflicts that developed in Southeast Asia in the 1950s and early 1960s. Vietnam and Laos were engulfed in internal wars with external involvement, and conflict ultimately spread to Cambodia. Further conflicts revolved around Indonesia’s unstable internal political order and its opposition to Britain’s efforts to secure the positions of its colonial territories in the region by fostering a federation that could include Malaya, Singapore and the states of North Borneo. The Federation of Malaysia was inaugurated in September 1963, but Singapore was forced to depart in August 1965 and became a separate state. ASEAN was established in August 1967 in an effort to ameliorate the serious tensions among the states that formed it, and to make a contribution towards a more stable regional environment. Australia was intensely interested in all these developments. To discuss these issues, this chapter covers in turn the background to the emergence of interest in regional cooperation in Southeast Asia after the Second World War, the period of Indonesia’s Konfrontasi of Malaysia, the formation of ASEAN and the inauguration of multilateral relations with ASEAN in 1974 by Gough Whitlam’s government, and Australia’s early interactions with ASEAN in the period 1974‒75. 7 ENGAGING THE NEIGHBOURS The Cold War era and early approaches towards regional cooperation The conception of ‘Southeast Asia’ as a distinct region in which states might wish to engage in regional cooperation emerged in an environment of international conflict and the end of the era of Western colonialism.1 Extensive communication and interactions developed in the pre-colonial era, but these were disrupted thoroughly by the arrival of Western powers. -

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: from Cold War to Conditionality

ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: From Cold War to Conditionality Lee Jones Abstract Despite their other theoretical differences, virtually all scholars of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) agree that the organisation’s members share an almost religious commitment to the norm of non-intervention. This article disrupts this consensus, arguing that ASEAN repeatedly intervened in Cambodia’s internal political conflicts from 1979-1999, often with powerful and destructive effects. ASEAN’s role in maintaining Khmer Rouge occupancy of Cambodia’s UN seat, constructing a new coalition government-in-exile, manipulating Khmer refugee camps and informing the content of the Cambodian peace process will be explored, before turning to the ‘creeping conditionality’ for ASEAN membership imposed after the 1997 ‘coup’ in Phnom Penh. The article argues for an analysis recognising the political nature of intervention, and seeks to explain both the creation of non- intervention norms, and specific violations of them, as attempts by ASEAN elites to maintain their own illiberal, capitalist regimes against domestic and international political threats. Keywords ASEAN, Cambodia, Intervention, Norms, Non-Interference, Sovereignty Contact Information Lee Jones is a doctoral candidate in International Relations at Nuffield College, Oxford, OX1 1NF, UK. His research focuses on ASEAN and intervention in Cambodia, East Timor, and Burma. Comments are welcomed. Email: [email protected]. Tel/Fax: (+44) (0)1865 28890. ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: -

4 at the 34'^^ ASEAN Summit Earlier This Year, Our Leaders Reiterated

STATEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS BY AMBASSADOR BURHAN GAFOOR, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF THE REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE TO THE UNITED NATIONS, AT THE THEMATIC DEBATE ON CLUSTER FIVE: OTHER DISARMAMENT MEASURES AND INTERNATIONAL SECURITY, FIRST COMMITTEE, 29 OCTOBER 2019 Thank you, Mr Chairman. 1 I have the honour to deliver this statement on behalf of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations(ASEAN). Our statement will focus on cybersecurity, on which I will make three points. 2 First, ASEAN's vision is for a peaceful, secure, and resilient cyberspace, which serves as an enabler of economic progress, enhanced regional connectivity and the betterment of living standards for all. Digital transformation will have tremendous benefits and opportunities for our region. At the same time, we are cognisant that pervasive, ever-evolving, and transboundary cyber threats have the potential to undemiine international peace and security. To this end, ASEAN believes that cybersecurity requires coordinated expertise from multiple stakeholders from across different domains, to effectively mitigate threats, build trust, and realise the benefits of technology. 3 Second, no govemment can deal with the growing sophistication and transboundary nature of cyber threats alone. Regional collaboration is imperative, and ASEAN has taken concrete and practical steps to this end. 4 At the 34'^^ ASEAN Summit earlier this year, our Leaders reiterated ASEAN's commitment to enhancing cybersecurity cooperation, and the building of an open, secure, stable, accessible, and resilient cyberspace supporting the digital economy of the ASEAN region. At the 3^^^ ASEAN Ministerial Conference on Cybersecurity(AMCC) in September 2018, ASEAN became the first and only regional group to subscribe to the 11 voluntaiy, non-binding norms recommended in the 2015 report of the UN Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security (UNGGE). -

The Role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Democracy Support

The role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in post-conflict reconstruction and democracy support www.idea.int THE ROLE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS IN POST- CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION AND DEMOCRACY SUPPORT Julio S. Amador III and Joycee A. Teodoro © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34, STOCKHOLM SWEDEN Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit thepublication as well as to remix and adapt it provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information on this licence see: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Graphic design by Turbo Design CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. ASEAN’S INSTITUTIONAL MANDATES ............................................................... 5 3. CONFLICT IN SOUTH-EAST ASIA AND THE ROLE OF ASEAN ...... 7 4. ADOPTING A POST-CONFLICT ROLE FOR -

The Struggle of Becoming the 11Th Member State of ASEAN: Timor Leste‘S Case

The Struggle of Becoming the 11th Member State of ASEAN: Timor Leste‘s Case Rr. Mutiara Windraskinasih, Arie Afriansyah 1 1 Faculty of Law, Universitas Indonesia E-mail : [email protected] Submitted : 2018-02-01 | Accepted : 2018-04-17 Abstract: In March 4, 2011, Timor Leste applied for membership in ASEAN through formal application conveying said intent. This is an intriguing case, as Timor Leste, is a Southeast Asian country that applied for ASEAN Membership after the shift of ASEAN to acknowledge ASEAN Charter as its constituent instrument. Therefore, this research paper aims to provide a descriptive overview upon the requisites of becoming ASEAN Member State under the prevailing regulations. The substantive requirements of Timor Leste to become the eleventh ASEAN Member State are also surveyed in the hopes that it will provide a comprehensive understanding as why Timor Leste has not been accepted into ASEAN. Through this, it is to be noted how the membership system in ASEAN will develop its own existence as a regional organization. This research begins with a brief introduction about ASEAN‘s rules on membership admission followed by the practice of ASEAN with regard to membership admission and then a discussion about the effort of Timor Leste to become one of ASEAN member states. Keywords: membership, ASEAN charter, timor leste, law of international and regional organization I. INTRODUCTION South East Asia countries outside the The 1967 Bangkok Conference founding father states to join ASEAN who produced the Declaration of Bangkok, which wish to bind to the aims, principles and led to the establishment of ASEAN in August purposes of ASEAN. -

ASEAN's Pattaya Problem by Donald K Emmerson

ASEAN's Pattaya problem By Donald K Emmerson The turmoil in Thailand is about domestic questions: who shall rule the kingdom, and what is the future of democracy there? But the crisis also raises questions for the larger region: who will lead the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and what is the future of democracy in Southeast Asia? In mid-2008, Thailand began its tenure as ASEAN's chair. The chair is expected, at a minimum, to host successfully the association's main events, most notably the ASEAN summit and multiple other summits between Southeast Asia's leaders and those of other countries. Accordingly, Thailand had planned to welcome the heads of ASEAN's other nine member government plus their counterparts from Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea in a series of meetings in the Thai resort town of Pattaya on April 10-12. (The other nine are Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Myanmar, Laos, Brunei, Cambodia and Indonesia.) Summitry called for decorum - serene images of Thai leaders greeting their distinguished guests. Bedlam came closer to describing the scene in Pattaya when Thai protesters opposed to the new government of Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva stormed the summit's venue and forced its cancellation. Heads of state and government who had already arrived at the seaside resort 150 kilometers southeast of Bangkok were evacuated by helicopter. Planes carrying other leaders to Thailand were turned back in mid-flight. No one blames ASEAN for Thailand's political travails. Because of it, however, the regional organization has lost major face. -

Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015

Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 One Vision, One Identity, One Community Association of Southeast Asian Nations Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established on 8 August 1967. The Member States of the Association are Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat is based in Jakarta, Indonesia. For inquiries, contact: Public Affairs Office The ASEAN Secretariat 70A Jalan Sisingamangaraja Jakarta 12110 Indonesia Phone : (62 21) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (62 21) 739-8234, 724-3504 E-mail : [email protected] General information on ASEAN appears online at the ASEAN Website: www.asean.org Catalogue-in-Publication Data Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat, April 2009 352.1159 1. ASEAN – Summit – Blueprints 2. Political-Security – Economic – Socio-Cultural ISBN 978-602-8411-04-2 The text of this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Copyright ASEAN Secretariat 2009 All rights reserved ii Roadmap for an ASEAN Community 2009-2015 Table of Contents Cha-am Hua Hin Declaration on the Roadmap for the ASEAN Community (2009-2015) ..........................01 ASEAN Political-Security Community Blueprint .........................................................................................05 ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint ....................................................................................................21