Leptailurus Serval – Serval

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation of the Wildcat (Felis Silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the Conservation Status and Assessment of Conservation Activities

Conservation of the wildcat (Felis silvestris) in Scotland: Review of the conservation status and assessment of conservation activities Urs Breitenmoser, Tabea Lanz and Christine Breitenmoser-Würsten February 2019 Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 2 Cover photo: Wildcat (Felis silvestris) male meets domestic cat female, © L. Geslin. In spring 2018, the Scottish Wildcat Conservation Action Plan Steering Group commissioned the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group to review the conservation status of the wildcat in Scotland and the implementation of conservation activities so far. The review was done based on the scientific literature and available reports. The designation of the geographical entities in this report, and the representation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The SWCAP Steering Group contact point is Martin Gaywood ([email protected]). Wildcat in Scotland – Review of Conservation Status and Activities 3 List of Content Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Summary 5 1. Introduction 7 2. History and present status of the wildcat in Scotland – an overview 2.1. History of the wildcat in Great Britain 8 2.2. Present status of the wildcat in Scotland 10 2.3. Threats 13 2.4. Legal status and listing 16 2.5. Characteristics of the Scottish Wildcat 17 2.6. Phylogenetic and taxonomic characteristics 20 3. Recent conservation initiatives and projects 3.1. Conservation planning and initial projects 24 3.2. Scottish Wildcat Action 28 3.3. -

Felis Silvestris, Wild Cat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T60354712A50652361 Felis silvestris, Wild Cat Assessment by: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. 2015. Felis silvestris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T60354712A50652361. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information -

African Wildcat 1 African Wildcat

African Wildcat 1 African Wildcat African Wildcat[1] Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Felis Species: F. silvestris Subspecies: F. s. lybica Trinomial name Felis silvestris lybica Forster, 1770 The African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), also known as the desert cat, and Vaalboskat (Vaal-forest-cat) in Afrikaans, is a subspecies of the wildcat (F. silvestris). They appear to have diverged from the other subspecies about 131,000 years ago.[2] Some individual F. s. lybica were first domesticated about 10,000 years ago in the Middle East, and are among the ancestors of the domestic cat. Remains of domesticated cats have been included in human burials as far back as 9,500 years ago in Cyprus.[3] [4] Physical characteristics The African wildcat is sandy brown to yellow-grey in color, with black stripes on the tail. The fur is shorter than that of the European subspecies. It is also considerably smaller: the head-body length is 45 to 75 cm (17.7 to 29.5 inches), the tail 20 to 38 cm (7.87 to 15 inches), and the weight ranges from 3 to 6.5 kg (6.61 to 14.3 lbs). Distribution and habitat The African wildcat is found in Africa and in the Middle East, in a wide range of habitats: steppes, savannas and bushland. The sand cat (Felis margarita) is the species found in even more arid areas. Skull African Wildcat 2 Behaviour The African wildcat eats primarily mice, rats and other small mammals. When the opportunity arises, it also eats birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. -

Serval Fact Sheet

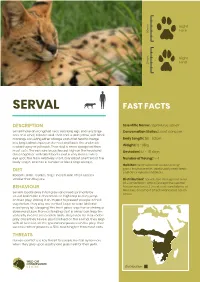

Right 50mm Fore Right 50mm Hind SERVAL FAST FACTS DESCRIPTION Scientific Name: Leptailurus serval Servals have an elongated neck, very long legs, and very large Conversation Status: Least concern ears on a small, delicate skull. Their coat is pale yellow, with black markings consisting either of large spots that tend to merge Body Length: 59 - 92cm into longitudinal stripes on the neck and back. The underside is whitish grey or yellowish. Their skull is more elongated than Weight: 12 - 18kg most cats. The ears are broad based, high on the head and Gestation: 67 - 79 days close together, with black backs and a very distinct white eye spot. The tail is relatively short, only about one third of the Number of Young: 1 - 4 body length, and has a number of black rings along it. Habitat: Well-watered savanna long- grass environments, particularly reed beds DIET and other riparian habitats. Rodents, birds, reptiles, frogs, insects and other species smaller than they are. Distribution: Servals live throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa (except the central BEHAVIOUR African rainforest), the deserts and plains of Namibia, and most of Botswana and South Servals locate prey in tall grass and reeds primarily by Africa. sound and make a characteristic high leap as they jump on their prey, striking it on impact to prevent escape in thick vegetation. They also use vertical leaps to seize bird and insect prey by “clapping” the front paws together or striking a downward blow. From a standing start a serval can leap 3m vertically into the air to catch birds. -

1 the Origin and Evolution of the Domestic Cat

1 The Origin and Evolution of the Domestic Cat There are approximately 40 different species of the cat family, classification Felidae (Table 1.1), all of which are descended from a leopard-like predator Pseudaelurus that existed in South-east Asia around 11 million years ago (O’Brien and Johnson, 2007). Other than the domestic cat, the most well known of the Felidae are the big cats such as lions, tigers and panthers, sub-classification Panthera. But the cat family also includes a large number of small cats, including a group commonly known as the wildcats, sub-classification Felis silvestris (Table 1.2). Physical similarity suggests that the domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus) originally derived from one or more than one of these small wildcats. DNA examination shows that it is most closely related to the African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), which has almost identical DNA, indicating that the African wildcat is the domestic cat’s primary ancestor (Lipinski et al., 2008). The African Wildcat The African wildcat is still in existence today and is a solitary and highly territorial animal indigenous to areas of North Africa and the Near East, the region where domestication of the cat is believed to have first taken place (Driscoll et al., 2007; Faure and Kitchener, 2009). It is primarily a nocturnal hunter that preys mainly on rodents but it will also eat insects, reptiles and other mammals including the young of small antelopes. Also known as the Arabian or North African wildcat, it is similar in appearance to a domestic tabby, with a striped grey/sandy-coloured coat, but is slightly larger and with longer legs (Fig. -

Leptailurus Serval)

animals Article The Effect of Behind-The-Scenes Encounters and Interactive Presentations on the Welfare of Captive Servals (Leptailurus serval) Lydia K. Acaralp-Rehnberg 1,*, Grahame J. Coleman 1, Michael J. L. Magrath 2, Vicky Melfi 3, Kerry V. Fanson 4 and Ian M. Bland 1 1 Animal Welfare Science Centre, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; [email protected] (G.J.C.); [email protected] (I.M.B.) 2 Department of Wildlife Conservation and Science, Zoos Victoria, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; [email protected] 3 Hartpury University, Gloucester GL193BE, UK; vicky.melfi@hartpury.ac.uk 4 Centre for Integrative Ecology, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria 3216, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-404-761-714 Received: 13 April 2020; Accepted: 15 April 2020; Published: 24 April 2020 Simple Summary: Live animal encounter programs are an increasingly popular occurrence in the modern zoo. The effects of such encounters on program animal welfare have not been studied extensively to date. The aim of this study was, therefore, to explore animal welfare effects associated with encounter programs in a small felid, the serval, which is commonly involved as a program animal in zoos. Specifically, this study investigated how serval behaviour and adrenocortical activity (level of faecal cortisol metabolites) were affected by short-term variations in encounter frequency. Over the course of the study, the frequency of encounters was manipulated so that servals alternated between four different treatments, involving interactive presentations, behind-the-scenes encounters, both activities combined, or no interaction at all. -

Savannah Cat’ ‘Savannah the Including Serval Hybrids Felis Catus (Domestic Cat), (Serval) and (Serval) Hybrids Of

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Serval hybrids Hybrids of Leptailurus serval (serval) and Felis catus (domestic cat), including the ‘savannah cat’ Anna Markula, Martin Hannan-Jones and Steve Csurhes First published 2009 Updated 2016 © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/au/deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Front cover: Close-up of a 4-month old F1 Savannah cat. Note the occelli on the back of the relaxed ears, and the tear-stain markings which run down the side of the nose. Photo: Jason Douglas. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a Public Domain Licence. Invasive animal risk assessment: Savannah cat Felis catus (hybrid of Leptailurus serval) 2 Contents Introduction 4 Identity of taxa under review 5 Identification of hybrids 8 Description 10 Biology 11 Life history 11 Savannah cat breed history 11 Behaviour 12 Diet 12 Predators and diseases 12 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats (overseas) 13 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats -

Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat

UPTEC X 12 012 Examensarbete 30 hp Juni 2012 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Molecular Biotechnology Programme Uppsala University School of Engineering UPTEC X 12 012 Date of issue 2012-06 Author Carolin Johansson Title (English) Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Title (Swedish) Abstract This study presents mitochondrial genome sequences from 22 Egyptian house cats with the aim of resolving the uncertain origin of the contemporary world-wide population of Domestic cats. Together with data from earlier studies it has been possible to confirm some of the previously suggested haplotype identifications and phylogeny of the Domestic cat lineage. Moreover, by applying a molecular clock, it is proposed that the Domestic cat lineage has experienced several expansions representing domestication and/or breeding in pre-historical and historical times, seemingly in concordance with theories of a domestication origin in the Neolithic Middle East and in Pharaonic Egypt. In addition, the present study also demonstrates the possibility of retrieving long polynucleotide sequences from hair shafts and a time-efficient way to amplify a complete feline mitochondrial genome. Keywords Feline domestication, cat in ancient Egypt, mitochondrial genome, Felis silvestris libyca Supervisors Anders Götherström Uppsala University Scientific reviewer Jan Storå Stockholm University Project name Sponsors Language Security English Classification ISSN 1401-2138 Supplementary bibliographical information Pages 123 Biology Education Centre Biomedical Center Husargatan 3 Uppsala Box 592 S-75124 Uppsala Tel +46 (0)18 4710000 Fax +46 (0)18 471 4687 Origin of the Egyptian Domestic Cat Carolin Johansson Populärvetenskaplig sammanfattning Det är inte sedan tidigare känt exakt hur, när och var tamkatten domesticerades. -

Status of the African Wild Dog in the Bénoué Complex, North Cameroon

Croes et al. African wild dogs in Cameroon Copyright © 2012 by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISSN 1478-2677 Distribution Update Status of the African wild dog in the Bénoué Complex, North Cameroon 1* 2,3 1 1 Barbara Croes , Gregory Rasmussen , Ralph Buij and Hans de Iongh 1 Institute of Environmental Sciences (CML), University of Leiden, The Netherlands 2 Painted dog Conservation (PDC), Hwange National Park, Box 72, Dete, Zimbabwe 3 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK * Correspondence author Keywords: Lycaon pictus, North Cameroon, monitoring surveys, hunting concessions Abstract The status of the African wild dog Lycaon pictus in the West and Central African region is largely unknown. The vast areas of unspoiled Sudano-Guinean savanna and woodland habitat in the North Province of Cameroon provide a potential stronghold for this wide-ranging species. Nevertheless, the wild dog is facing numerous threats in this ar- ea, mainly caused by human encroachment and a lack of enforcement of laws and regulations in hunting conces- sions. Three years of surveys covering over 4,000km of spoor transects and more than 1,200 camera trap days, in addition to interviews with local stakeholders revealed that the African wild dog in North Cameroon can be consid- ered functionally extirpated. Presence of most other large carnivores is decreasing towards the edges of protected areas, while presence of leopard and spotted hyaena is negatively associated with the presence of villages. Lion numbers tend to be lower inside hunting concessions as compared to the national parks. -

THE INTERNATIONAL CAT ASSOCIATION, INC. (Open Session

THE INTERNATIONAL CAT ASSOCIATION, INC. 2007 Annual Board Meeting August 29-31, 2007 Albuquerque, NM (Open Session) August 29, 2007, Wednesday, 8 AM ACTION TIME PAGE Welcome and Call to Order DeVilbiss Verbal 8-8:30AM - 1. Roll Call DeVilbiss Verbal - 2. President's Remarks DeVilbiss Verbal - (Executive Session) 8:30-11:30AM See Executive Agenda Lunch - 11:30AM-1PM (Open Session) Consent Agenda 1:00-1:15PM 1. Annual Awards Report EO Approve 5 2. License Fee Report EO Approve 7 3. Insurance Report EO Approve 9 4. Active Regional Clubs EO Approve Previously furnished - 5. Dom X Dom Litters Registered - None EO Approve - 6. Future Annuals, Semi-Annuals EO Approve 11 7. Minutes, Corrections/Additions EO Approve - 8. TICA TREND Editor Contract BOD Approve 12 9. Pet Pac Donation BOD Approve - 10. Reiss Design Assoc Agreement BOD Approve 15 Board Governance 1:15-2:00PM 1. Review Board Governance Policy Fisher Approve - a. Publish Minutes of the Meeting Fisher Add and Approve - 2. Review follow-up status report Fisher Approve 17 Fiduciary 2:00-3:00PM 1. 2007-2008 Budget Review EO Information 18 2. Overtime Report (End of Fiscal Year) EO Information 23 3. TDS Revenue FY 06-07 EO Information 24 4. Credit Card Info and new Addendum EO Approval 25 5. TICA TREND Final Report EO Information 32 Page 1 2007 Annual Meeting Agenda, Page 1 Discussions 3:00-5:00PM 1. Results-Russian Poll on Isolated Status Wood Discussion - 2. Results-American Bobtail Poll Crockett Discussion - 3. TICA FR CN club-NEW organization Christian Discussion - 4. -

Table S2 RABV Sequences Used for Phylogenetic Analysis with African Civet Sequences (Figure 2)

Table S2 RABV sequences used for phylogenetic analysis with African civet sequences (Figure 2). All are complete N gene sequences unless indicated otherwise. Sequences used in Figure 3 Bayesian host trait analysis are underlined. GenBank ID Original ID Country Host Year Isolated RABV Variant AB284514 ZAMRAV23/0 Zambia Dog 2004 Africa 1 4 Canid AF467949 710/90 RSA Cynictis penicillata 1990 Africa 3 Mongoose DQ837461 S1-81 Egypt Dog 1999 Africa 4 DQ837462 S2-81 Egypt Dog 1999 Africa 4 DQ837463 S3-81 Egypt Dog 1999 Africa 4 EU718759 Chad_71_164 Chad Dog 2005 Africa 2 EU853569 9016MAR Morocco Dog 1990 Africa 2 EU835375 Tunisia Human 1986 Africa 2 EU853581 8808ETH Ethiopia Dog 1988 Africa 1 Canid EU853586 07128RCA CAR Dog 2003 Africa 2 FJ392366 19-92 RSA Mongoose 1992 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392367 22107 Zim Slender Mongoose 2001 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392368 23-01 RSA Meerkat 2001 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392369 28-00 RSA Slender Mongoose 2000 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392370 30-00 RSA Bovine 2000 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392371 32-02 RSA Yellow Mongoose 2002 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392372 113-91 RSA Atilux paludinosus 1991 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392373 155-03 RSA Slender Mongoose 2003 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392374 211-98 RSA Canine 1998 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392375 221-98 RSA Suricata suricatta 1998 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392376 228-01 RSA Sheep 2001 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392377 279-99 RSA Yellow Mongoose 1999 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392378 344-99 RSA Yellow Mongoose 1999 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392379 364-96 RSA Mongoose 1996 Africa 3 Mongoose FJ392380 381-06 RSA Yellow Mongoose 2006 -

Hybrid Cats’ Position Statement, Hybrid Cats Dated January 2010

NEWS & VIEWS AAFP Position Statement This Position Statement by the AAFP supersedes the AAFP’s earlier ‘Hybrid cats’ Position Statement, Hybrid cats dated January 2010. The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) strongly opposes the breeding of non-domestic cats to domestic cats and discourages ownership of early generation hybrid cats, due to concerns for public safety and animal welfare issues. Unnatural breeding between intended mates can make The AAFP strongly opposes breeding difficult. the unnatural breeding of non- Domestic cats have 38 domestic to domestic cats. This chromosomes, and most commonly includes both natural breeding bred non-domestic cats have 36 and artificial insemination. chromosomes. This chromosomal The AAFP opposes the discrepancy leads to difficulties unlicensed ownership of non- in producing live births. Gestation domestic cats (see AAFP’s periods often differ, so those ‘Ownership of non-domestic felids’ kittens may be born premature statement at catvets.com). The and undersized, if they even AAFP recognizes that the offspring survive. A domestic cat foster of cats bred between domestic mother is sometimes required cats and non-domestic (wild) cats to rear hybrid kittens because are gaining in popularity due to wild females may reject premature their novelty and beauty. or undersized kittens. Early There are two commonly seen generation males are usually hybrid cats. The Bengal (Figure 1), sterile, as are some females. with its spotted coat, is perhaps The first generation (F1) female the most popular hybrid, having its offspring of a domestic cat bred to origins in the 1960s. The Bengal a wild cat must then be mated back is a cross between the domestic to a domestic male (producing F2), cat and the Asian Leopard Cat.