Hazards Or Hassles: the Effect of Sanctions on Leader Survival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhutan Final Report National Assembly Elections 24 March 2008

BHUTAN FINAL REPORT National Assembly Elections, 24 March 2008 21 May 2008 EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION This report was produced by the EU Election Observation Mission and presents the EU EOM’s findings on the 24 March 2008 National Assembly elections in Bhutan. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the Commission. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. EU Election Observation Mission, Bhutan 2008 Final Report Final Report on the National Assembly Elections – 24 March 2008 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................. 3 II. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 6 III. POLITICAL BACKGROUND...................................................................................... 6 A: Political Context........................................................................................................ 6 B: Key Political Actors................................................................................................... 7 IV. IV. LEGAL ISSUES........................................................................................................ 7 A: Legal Framework...................................................................................................... -

2Nd Parliament of Bhutan 9Th Session

2ND PARLIAMENT OF BHUTAN 9TH SESSION Resolution No. 9 PROCEEDINGS AND RESOLUTION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF BHUTAN (May 3 - June 20, 2017) Speaker: Jigme Zangpo Table of Content 1. Inaugural Ceremony..........................................................................1 2. Resolution of Joint Sitting on the Bhutan Customs Bills 2017.........................................................................................3 3. The National Budget Report for the Financial Year 2017-18..............................................................................................5 4. Question Hour: Group A- Questions asked to the Prime Minister, Minister for Information and Communication...............16 5. The Local Government Pay Revision Report 2017.........................18 6. Resolution on the Motion for the First and Second Reading of the Anti-money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Bill 2017....................................................................21 7. Resolution on the Third Reading of the Marriage Bill of Bhutan 2017...............................................................................23 8. Resolution on the Local Government Petition to upgrade Zhemgang Central School to a College .........................................26 9. Question Hour: Group B- Questions asked to the Minister for Works and Human Settlement, Minister for Education and Minister for Foreign Affairs.....................................................29 10. Report on the Implementation Status to Encourage the Private Sector -

Newsletter 38

THE BHUTAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Number 38 President: Lord Wilson of Tillyorn, KT GCMG FRSE Summer 2008 Coronation date The 16th Annual Dinner announced of the Bhutan Society See page 3 10th October, 2008 Bhutan: the world’s youngest democracy See pages 3, 4, 5 & 6 Application form enclosed. See also page 2 Recent Events in Bhutan From Lord Wilson of Tillyorn An informal talk by Michael Rutland President of the Bhutan Society he Bhutan Society of the Monday 8th September, 2008 TUK has now been in existence for just over 15 Michael Rutland, our Hon. Secretary and Bhutan’s Hon. years. During that time I have Consul to the UK, will again present his very popular had the great pleasure annual roundup of news from Bhutan. This year has seen and honour of being President. Bhutan’s successful emergence as the world’s youngest It has been a joy to see the democracy, and the coronation of the 5th King will take Society grow, flourish and place in November. A momentous year indeed! contribute both to a greater Michael, who lives in Bhutan for much of each year, is understanding of the Kingdom particularly well placed to discuss the changes and of Bhutan and, in small developments taking place in the country, perhaps spiced practical ways, to the well- with the odd bit of gossip! His talk will be illustrated with being of organizations and individuals there. slides and there will be plenty of opportunity for The time has come to make changes in the organisation questions. of the Society and to plan ahead for the future. -

Portrait of a Leader

Portrait of a Leader Portrait of a Leader Through the Looking-Glass of His Majesty’s Decrees Mieko Nishimizu The Centre for Bhutan Studies Portrait of a Leader Through the Looking-Glass of His Majesty’s Decrees Copyright © The Centre for Bhutan Studies, 2008 First Published 2008 ISBN 99936-14-43-2 The Centre for Bhutan Studies Post Box No. 1111 Thimphu, Bhutan Phone: 975-2-321005, 321111,335870, 335871, 335872 Fax: 975-2-321001 e-mail: [email protected] www.bhutanstudies.org.bt To Three Precious Jewels of the Thunder Dragon, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, Druk Gyalpo IV, His Majesty Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, Druk Gyalpo V and The People of Bhutan, of whom Druk Gyalpo IV has said, “In Bhutan, whether it is the external fence or the internal wealth, it is our people.” The Author of Gross National Happiness, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the Fourth Druk Gyalpo of the Royal Kingdom of Bhutan CONTENTS Preface xi 2 ENVISIONING THE FUTURE 1 To the Director of Health 6 2 To Special Commission 7 3 To Punakha Dratshang 8 4 To the Thrompon, Thimphu City Corporation 9 5 To the Planning Commission 10 6 To the Dzongdas, Gups, Chimis and the People 13 7 To the Home Minister 15 18 JUSTICE BORN OF HUMILITY 8 Kadoen Ghapa (Charter C, issued to the Judiciary) 22 9 Kadoen Ghapa Ka (Charter C.a, issued to the Judiciary) 25 10 Kadoen Ngapa (Chapter 5, issued to the Judiciary) 28 11 Charter pertaining to land 30 12 Charter (issued to Tshering) 31 13 To the Judges of High Court 33 14 To the Home Minister 36 15 Appointment of the Judges 37 16 To -

The 9Th Annual General Meeting of Drc ”

Newsletter DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE AND CUSTOMS MINISTRY OF FINANCE BHUTAN Jan/Feb 2003 ISSUE 13 THE 9TH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF DRC THE 9 TH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING of the and it was also the first year of PIT. He Department of Revenue and Customs was held informed that the revenue projection would In this Issue from November 25-30, 2002 at the conference be discussed and added that the tax hall, Regional Revenue and Customs Office, incentives announced by the RGOB will The 9th AGM .................................. 1 Thimphu. Over 50 participants attended the have a negative effect on revenue in the News in Brief ............................... 2 meeting from five Regional Revenue and short run, but in the long run greater PIT Awareness Campaign............. 3 Articles ......................................... 4-5 Customs Offices, Head Office, Liaison & Transit revenue would be generated from the new Face to Face ................................. 6 Office and Ministry of Finance. industries that are established in response Comments from the Field ............ 7 The objectives of the meeting were: to the incentives. Administration & Personnel ........ 8-10 ● To review the revenue projection for In-country Training....................... 9 2002-03 and progress in revenue Ex-country Training...................... 9 collection. The whole department Around the Divisions .................. 11 “ Around the Regions ...................12-13 ● To share field experiences and resolve should be equally Highlights: 8th FYP & common issues/problems -

1 Father Estevao Cacella's Report on Bhutan in 1627

FATHER ESTEVAO CACELLA'S REPORT ON BHUTAN IN 1627 Luiza Maria Baillie** Abstract The article introduces a translation of the account written in 1627 by the Jesuit priest Father Estevao Cacella, of his journey with his companion Father Joao Cabral, first through Bengal and then through Bhutan where they stayed for nearly eight months. The report is significant because the Fathers were the first Westerners to visit and describe Bhutan. More important, the report gives a first-hand account of Shabdrung Ngawang Namgyel, the Founder of Bhutan. Introduction After exploring the Indian Ocean in the 15th century, the Portuguese settled as traders in several ports of the coast of India, and by mid 16th century Jesuit missionaries had been established in the Malabar Coast (the main centres being Cochin and Goa), in Bengal and in the Deccan. The first Jesuit Mission disembarked in India in 1542 with the arrival of Father Francis Xavier, proclaimed saint in 1622. * Luiza Maria Baillie holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree in English and French from Natal University, South Africa, and a Teacher's Certificate from the College of Education, Aberdeen, Scotland. She worked as a secretary and a translator, and is retired now. * Acknowledgements are due to the following who provided information, advice, encouragement and support. - Monsignor Cardoso, Ecclesiastic Counsellor at the Portuguese Embassy, the Vatican, Rome. - Dr. Paulo Teodoro de Matos of 'Comissao dos Descobrimentos Portugueses'; Lisbon, Portugal. - Dr. Michael Vinding, Counsellor, Resident Coordinator, Liaison Office of Denmark, Thimphu. 1 Father Estevao Cacella's Report on Bhutan in 1627 The aim of the Jesuits was to spread Christianity in India and in the Far East, but the regions of Tibet were also of great interest to them. -

Bhutan: Political Reform in a Buddhist Monarchy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo BHUTAN: POLITICAL REFORM IN A BUDDHIST MONARCHY Thierry Mathou*, March 1999 The Fifteenth Day of the Fourth Month of the Year of the Male Earth Tiger, corresponding to 10th June 1998, will probably stay as a milestone date in Bhutan's modern history. HM Jigme Singye Wangchuck, the fourth King of Bhutan, known to his subjects as the Druk Gyalpo, has issued a kasho (royal edict) that could bring profound changes in the kingdom’s everyday life. By devolving full executive powers to an elected cabinet, the authority of which will be defined by the National Assembly during its 1999 session, and introducing the principle of his own political responsibility, the King has opened a new page in Himalayan politics. Although being a small country which has always been very cautious on the international scene, Bhutan, as a buffer state, nested in the heart of the Himalayas, between India and China, has a strategic position in a region where the divisive forces of communalism are vivid. The kingdom, which has long stayed out of the influence of such forces, is now facing potential difficulties with the aftermath of the so called ngolop1 issue and the impact of ULFA-Bodo activity across the border with India, that threatens its political stability and internal security. The process of change in Bhutan is not meant to fit in any regional model that could be inspired by Indian or Nepalese politics. However there is a clear interaction between national and regional politics. -

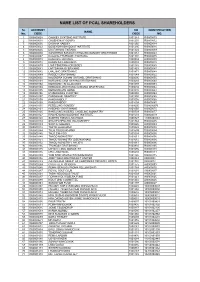

Name List of Pcal Shareholders

NAME LIST OF PCAL SHAREHOLDERS Sl. ACCOUNT CD IDENTIFICATION NAME No. CODE CODE NO. 1 1000000028 CHOKEY GYATSHO INSTITUTE 1001244 RI0000010 2 1000000030 CHUENGNAY GOMPA 1001250 RI0000012 3 1000000035 DAGANA RABDEY 1001260 RI0000014 4 1000000042 DODEYDRA BHUDDIST INSTITUTE 1001295 RI0000016 5 1000000046 DRATSHANG TSIRANG 1001324 RI0000019 6 1000000050 GANGTENG SANGAG CHHOLING GOMDEY DRATSHANG 1001051 RI0000023 7 1000000067 KAGUNG PHURSUM LHAKHANG 1001392 RI0000035 8 1000000070 KANJUR LHAKHANG 1000534 RI0000038 9 1000000072 KHAMLING LHAKHANG 1000393 RI0000040 10 1000000079 LAMI TSHERKHA DRUBDEY 1001183 RI0000045 11 1000000081 LAPTSAKHA GYERWANG 1001463 RI0000047 12 1000000082 LHALUNG DRATSHANG 1001471 RI0000048 13 1000000089 RABDEY DRATSHANG 1001549 RI0000052 14 1000000092 NALENDRA SONAM GATSHEL DRATSHANG 1000695 RI0000055 15 1000000101 NOBGANG CHULAKHANG DRATSHANG 1000693 RI0000060 16 1000000102 NORGANG TSHULAKHANG 1001093 RI0000061 17 1000000104 NOBGANG ZIMCHUNG GONGMA DRATSHANG 1000694 RI0000062 18 1000000105 NORGANG ZAI-GONG 1001030 RI0000063 19 1000000106 NYIZERGANG CHORTEN 1000803 RI0000064 20 1000000107 PANGKHAR, DROPDEY 1001500 RI0000065 21 1000000108 PARO RABDEY 1001005 RI0000066 22 1000000109 PARO RABDEY 1001009 RI0000067 23 1000000115 PESELLING GOMDEY 1000005 RI00000070 24 1000000121 RABDHEY DRATSHANG 1001060 RI0000075 25 1000000125 RANGJUNG WOESEL CHOELING MONASTRY 1000739 RI0000077 26 1000000127 RINCHENLING BUDDHIST INSTITUTE 1001558 RI0000079 27 1000000128 SAMTEN TSEMU LHAKHANG 1000827 11905000161 28 1000000134 SHA DECHENCHOLING -

3Rd Day of the 4Th Month of Earth Rat Year 08/05/2008

3rd day of the 4 th month of Earth Rat Year 08/05/2008 PROCEEDINGS AND RESOLUTIONS OF THE 1ST SESSION OF THE FIRST PARLIAMENT OF BHUTAN Time: 08:50 hrs I. Opening Ceremony 1. Escorting of His Majesty the King to the Assembly Hall At the commencement of the 1 st Session of the First Parliament of Bhutan on the auspicious 3 rd Day of the 4 th Month of the Earth Rat Year corresponding to May 8, 2008, His Majesty the King was received with elaborate Chipdrel and Serdrang procession to the National Assembly Hall. 2. Offering of Kusung Thukten Mendrel to His Majesty the King Members of Parliament from both the ruling and the opposition party offered Kusung Thukten Mendrel to His Majesty the King for His wellbeing and long life and also as a symbolic representation of their pledge to wholly commit in their solemn duties of ensuring the success of parliamentary democracy in the country as per the wishes of His Majesty King Jigme Singye Wangchuck. 3. Distribution of copies of the Draft Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan The Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee submitted the Draft Constitution of the Kingdom of 1 3rd day of the 4 th month of Earth Rat Year 08/05/2008 Bhutan, written in gold, to His Majesty the King following which copies of the Draft Constitution were distributed to the Members of Parliament. 4. Zhugdrel Phuensum Tshogpai ceremony The 1 st Session of the First Parliament opened with the offering of the elaborate traditional Zhugdrel Phuensum Tshogpai Tendrel . -

% @ 6I Two UNITED NATIONS PLAZA NEW YORK

% @ 6i Two UNITED NATIONS PLAZA NEW YORK. N.Y 10017 JML-BI998 PMB No.001.1/UN98.002 The Permanent Mission of the Kingdom of Bhutan to the United Nations presents its compliments to the Executive Office of the Secretary-General to the United Nations and has the honor to inform that the 76th Session of the National Assembly of the . Mim'sters and are also members of the Cabinet. His Majesty King Jigme Singye Wangchuck has awarded the Scarf of Office to the six elected Ministers on the fourth of July 1998. The Scarf of Office will be awarded to the newly elected Royal Advisory Councilors in October this year when the terms of the present Councilors' expire. The names_ of the new Cabinet Mini sters and jheir portfolios along with the names of the newly elected 1^ members of 'the Royal Advisory Council are attached to this note verbale. The Permanent Mission of the Kingdom of Bhutan to the United Nations avails itself of this opportunity to renew to Executive Office of the Secretary-General to the United Nations the assurances of its highest FVlE No.iJOs. S/UN9H.G02 Office of the Secretary-General : United Nations-S-3800- r; New York, NY 10017 printed on recycled paper Members of the Cabinet of the Royal Government of Bhutan 1. H.E. Lyonpo Jigmi Yoser Thinley Foreign Minister 2. H.E. Lyonpo Yeshey Zimba Finance Minister 3. H.E. Lyonpo Sangay Ngedup "Minister for Health and Education 4. H.E. Lyonpo Thinley Jamtsho Minister for Home 5. H.E. -

Sl.No CID No. Name & Address Remarks 1 10101005471

Druk Phuensum Tshogpa Members Sl.No CID No. Name & Address Remarks 1 10101005471 Gyeltshen, Dekiling Bumthang 2 10102000162 Dasho Karma Wangchuk Bumthang 3 10103002363 Lyonpo Pema Gyamtsho Bumthang 4 10201000699 Durga Dar Rai, P/Ling Chukha 5 10201000977 Birkha Bdr. Rai, P/Ling Chukha 6 10201002584 Ram Bdr. Limbu, Pasakha Chukha 7 10204000057 Chethey, Chapcha Chhakha 8 10204000798 Tandin Wangchuk, Gangkha Chukha 9 10204001378 Dophu, Dophu Transport Chukha 10 10204001387 Pelden Dorji Chhukha 11 10204001694 Dasho Ugay Tshering Chukha 12 10204001694 MP Ugay Tshering, Bongo-Chapcha Chhukha 13 10204001884 Karma Gyeltshen Chukha 14 10204001946 Tandin Wangchuk Chukha 15 10204002408 Chencho Dema, Umling Sarpang 16 10204002533 Tsenchok Thinley, Tashi Tours Chukha 17 10206000420 Dasho Chencho Dorji Chukha 18 10209000184 Sarbajit Rai, Logchina Chukha 19 10211001102 Kinga Dukpa, P/Ling Chukha 20 10211001167 Sangay Tshering, Dujaygang Dagana 21 10211002330 Kulman Rai, Pachu Chukha 22 10211002373 Bali Dlam Rai, Pachu Chukha 23 10211002792 Omtay Penjor, Yarkay Group Wangdue 24 10211003118 Dal Bdr. Rai, Phuentsholing Dagana 25 10211003482 Amber Bdr. Ghalley Samtse 26 10301000645 Mon Bdr. Subba, Dorona Dagana 27 10301001272 Dechen Uden, Chali Mongar 28 10303002700 Dasho Karma Rangdol Lhuntse 29 10304002357 Sabitria Chuwan, Dujeygang Dagana 30 10305001068 Kaka, DC Dagana 31 10306000850 Mon Bdr. Gurung, Drujeygang Dagana 32 10306001316 Lham Tshering Dagana 33 10306001399 Bal Bdr. Bal Tangmang, Pokto Dagana 34 10308000005 Lal Bahadur Bomzom, Tashiding Dagana -

BHUTAN YEARS of PARTNERSHIP 1989–2014 Imprint Publisher

AUSTRIA – BHUTAN YEARS OF PARTNERSHIP 1989–2014 IMPRINT Publisher: Austrian Development Agency (ADA), the operational unit of the Austrian Development Cooperation Zelinkagasse 2, 1010 Vienna, Austria www.entwicklung.at Editorial team: Françoise Pommaret Christine A. Jantscher in cooperation with the Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs, Directorate-General for Development Cooperation Graphic design: Alice Gutlederer Production: Grayling Austria Print: AV+Astoria, 1030 Vienna September 2014 TaBLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 2 Introduction 4 Dangpo, Dingpo 5 1989 – The Watershed Year 7 Mountain Forestry 10 Em-POWER-ment 13 Preserving Cultural Heritage 18 Excelling at Tourism 23 The Road to Democracy 27 Preventing Disasters 30 People to People 32 Annexes 35 1 FOREWORD his year marks the 25th anniversary of the establishment While much has been achieved over the past two decades, more Tof diplomatic relations between Bhutan and Austria. can be done to further this excellent relation. As we celebrate It is an occasion to celebrate the success achieved during our the Silver Jubilee of diplomatic relations, we must look beyond engagements over the past two-and-a-half decades and chart development cooperation and expand our engagement in other the course for the future. I believe that both countries have mutually beneficial areas and move towards a new chapter of ample reason to be satisfied with the development of our friendship that is even more meaningful and enduring. bilateral relations, which are defined by understanding, cooperation and above all, goodwill. This publication highlights the successful journey that Bhutan and Austria have made during the last 25 years. May Bhutan- Austria has over the decades generously shared its knowledge, Austrian relations flourish and grow from strength to strength.