Affectivity and Corporeal Transgression on Stage and Screen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Thomson CV

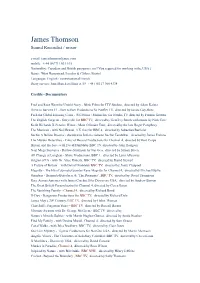

James Thomson Sound Recordist / mixer e-mail: [email protected] mobile: + 44 (0)7711 031 615 Nationality: Canadian and British passports ( no I Visa required for working in the USA ) Bases: West Hampstead, London & Clifton, Bristol Languages: English / conversational French Diary service: Jane Murch at Films at 59 + 44 ( 0)117 906 4334 Credits - Documentary Fred and Rose West the Untold Story - Blink Films for ITV Studios, directed by Adam Kaleta Drive to Survive F1 - Box to Box Productions for Netflix TV, directed by James Gay-Rees Push the Global Housing Crisis - WG Films / Malmo Inc for Netflix TV, directed by Fredrik Gertten The English Surgeon - Storyville for BBC TV, directed by Geoffrey Smith with music by Nick Cave Keith Richards X-Pensive Winos - Main Offender Tour, directed by the late Roger Pomphrey The Musicals - with Neil Brand, 3 X 1hrs for BBC 4, directed by Sebastian Barfield Sachin A Billion Dreams - docudrama Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar, directed by James Erskine The Murder Detectives - Films of Record Productions for Channel 4, directed by Bart Corpe Britain and the Sea - with David Dimbleby BBC TV, directed by John Hodgson Nazi Mega Stuctures - Darlow-Smithson for Nat Geo, directed by Simon Breen All Change at Longleat - Shine Productions, BBC 1, directed by Lynn Alleyway Origins of Us - with Dr. Alice Roberts, BBC TV, directed by David Stewart A Picture of Britain – with David Dimbleby BBC TV, directed by Jonty Claypool Magritte - The life of surrealist painter Rene Magritte for Channel 4, directed by Michael Burke Omnibus - Bernardo Bertolucci & ‘The Dreamers’, BBC TV, directed by David Thompson Race Across America with James Cracknell for Discovery USA, directed by Andrew Barron The Great British Paraorchestra for Channel 4, directed by Cesca Eaton The Vanishing Family - Channel 4, directed by Richard Bond D-Day - Dangerous Productions for BBC TV, directed by Richard Dale James May’s 20th Century, BBC TV, directed by Helen Thomas Churchill’s Forgotten Years – BBC TV, directed by Russell Barnes Ultimate Swarms with Dr. -

Hoi Polloi, 1989

SHELVED IN BOUND PERIODICALS ------------ -----· ---- hoi polloi* Staff Stacey Alexander Terry Hulsey Angie Roberts Faculty Advisors Thomas J. Sauret William Bradley Strickland V.l Il l •HOY-po-LOY: noun. 1. The common masses; the man in the street; the average person; the herd. 2. A literary publication of Gainesville College, comprised of nonfiction essays. Copy1ight 1989 by the Humanities Division of Gnincsvillc College. At> 2 \ t:...i 1 This publication consists of essays written by 'w'lq9~ e, ,f Gainesville College students. I hope that this slim vol ume of student writing helps illustrate what is right with Gainesville College. It clearly reflects the fact that the hoi polloi college attracts insightful, talented, a~ intelluctually curious students who take the time and effort to do more than what is required of them in a classroom. Only three of these essays were written as asignments for a writing course . This first Hoi Polloi attests that there is a place Table ofContents on campus for students who want more than a "drive through" education. All except one of these essays went through revisions and have been changed significantly by Wonderful Male Species.. ............................................. 3 the authors. These writers did not work for a grade; they By Diane Wall worked at the writing because they truly had something to say and they wanted to say it well. The Youth Syndrome.. ................................................5 By Stacey Alexander Hoi Polloi is a collection of the best non-fiction essays written at the College over the past year. The three Autumn............ ............................................................!! winners of the Gainesville College Writing Contest are By Teresa Smith included here. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

Quentin Tarantino's KILL BILL: VOL

Presents QUENTIN TARANTINO’S DEATH PROOF Only at the Grindhouse Final Production Notes as of 5/15/07 International Press Contacts: PREMIER PR (CANNES FILM FESTIVAL) THE WEINSTEIN COMPANY Matthew Sanders / Emma Robinson Jill DiRaffaele Villa Ste Hélène 5700 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 600 45, Bd d’Alsace Los Angeles, CA 90036 06400 Cannes Tel: 323 207 3092 Tel: +33 493 99 03 02 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] From the longtime collaborators (FROM DUSK TILL DAWN, FOUR ROOMS, SIN CITY), two of the most renowned filmmakers this summer present two original, complete grindhouse films packed to the gills with guns and guts. Quentin Tarantino’s DEATH PROOF is a white knuckle ride behind the wheel of a psycho serial killer’s roving, revving, racing death machine. Robert Rodriguez’s PLANET TERROR is a heart-pounding trip to a town ravaged by a mysterious plague. Inspired by the unique distribution of independent horror classics of the sixties and seventies, these are two shockingly bold features replete with missing reels and plenty of exploitative mayhem. The impetus for grindhouse films began in the US during a time before the multiplex and state-of- the-art home theaters ruled the movie-going experience. The origins of the term “Grindhouse” are fuzzy: some cite the types of films shown (as in “Bump-and-Grind”) in run down former movie palaces; others point to a method of presentation -- movies were “grinded out” in ancient projectors one after another. Frequently, the movies were grouped by exploitation subgenre. Splatter, slasher, sexploitation, blaxploitation, cannibal and mondo movies would be grouped together and shown with graphic trailers. -

Towards a Fifth Cinema

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Towards a fifth cinema Article (Accepted Version) Kaur, Raminder and Grassilli, Mariagiulia (2019) Towards a fifth cinema. Third Text, 33 (1). pp. 1- 25. ISSN 0952-8822 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/80318/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Towards a Fifth Cinema Raminder Kaur and Mariagiulia Grassilli Third Text article, 2018 INSERT FIGURE 1 at start of article I met a wonderful Nigerian Ph.D. -

Piers Morgan Outrage Over Brandpool Celebrity Trust Survey Submitted By: Friday's Media Group Monday, 19 April 2010

Piers Morgan outrage over Brandpool celebrity trust survey Submitted by: Friday's Media Group Monday, 19 April 2010 Piers Morgan has expressed outrage at being voted the sixth least trusted celebrity brand ambassador in a survey by ad agency and creative content providers Brandpool. Writing in his Mail On Sunday column, the Britain’s Got Talent judge questioned the logic of the poll, which named the celebrities the public would most and least trust as the faces of an ad campaign. But Brandpool has hit back at Morgan for failing to recognise the purpose of its research. Morgan, who also neglected to credit Brandpool as the source of the study, said: “No real surprises on the Most Trusted list, which is led by ‘national treasures’ such as David Attenborough, Stephen Fry, Richard Branson and Michael Parkinson. “As for the Least Trusted list, I find the logic of this one quite odd. Katie Price, for example, comes top, yet I would argue that she’s one of the most trustworthy people I know… Then I suddenly pop up at No 6, an outrage which perhaps only I feel incensed about. Particularly as that smiley little rodent Russell Brand slithers in at No 7. Making me supposedly less trustworthy than a former heroin junkie and sex addict.” Morgan was also surprised to see Simon Cowell, Cheryl Cole, Sharon Osbourne, Tom Cruise and Jonathan Ross in the Least Trusted list. However, he agreed with the inclusion of John Terry, Ashley Cole, Tiger Woods and Tony Blair, all of whom, he said, were “united by a common forked tongue”. -

24 Frames SF Tube Talk Reanimation in This Issue Movie News TV News & Previews Anime Reviews by Lee Whiteside by Lee Whiteside News & Reviews

Volume 12, Issue 4 August/September ConNotations 2002 The Bi-Monthly Science Fiction, Fantasy & Convention Newszine of the Central Arizona Speculative Fiction Society 24 Frames SF Tube Talk ReAnimation In This Issue Movie News TV News & Previews Anime Reviews By Lee Whiteside By Lee Whiteside News & Reviews The next couple of months is pretty slim This issue, we’ve got some summer ***** Sailor Moon Super S: SF Tube Talk 1 on genre movie releases. Look for success stories to talk about plus some Pegasus Collection II 24 Frames 1 Dreamworks to put Ice Age back in the more previews of new stuff coming this ***** Sherlock Hound Case File II ReAnimation 1 theatre with some extra footage in advance fall. **** Justice League FYI 2 of the home video release and Disney’s The big news of the summer so far is **** Batman: The Animated Series - Beauty & The Beast may show up in the success of The Dead Zone. Its debut The Legend Begins CASFS Business Report 2 regular theatre sometime this month. on USA Network on June 16th set **** ZOIDS : The Battle Begins Gamers Corner 3 September is a really dry genre month, with records for the debut of a cable series, **** ZOIDS: The High-Speed Battle ConClusion 4 only the action flick Ballistic: Eck Vs *** Power Rangers Time Force: Videophile 8 Sever on the schedules as of press time. Dawn Of Destiny Musty Tomes 15 *** Power Rangers Time Force: The End Of Time In Our Book (Book Reviews) 16 Sailor Moon Super S: Special Feature Pegasus Collection II Hary Potter and the Path to the DVD Pioneer, 140 mins, 13+ Secrets DVD $29.98 by Shane Shellenbarger 7 In Sailor Moon Super S, Hawkeye, Convention & Fandom Tigereye, and Fisheye tried to find Pegasus by looking into peoples dreams. -

Understanding a Serbian Film: the Effects of Censorship and File- Sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK Kapka, A

Understanding A Serbian Film: The Effects of Censorship and File- sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK Kapka, A. (2014). Understanding A Serbian Film: The Effects of Censorship and File-sharing on Critical Reception and Perceptions of Serbian National Identity in the UK. Frames Cinema Journal, (6). http://framescinemajournal.com/article/understanding-a-serbian-film-the-effects-of-censorship-and-file-sharing- on-critical-reception-and-perceptions-of-serbian-national-identity-in-the-uk/ Published in: Frames Cinema Journal Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2017 University of St Andrews and contributers.This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Speed Kills / Hannibal Production in Association with Saban Films, the Pimienta Film Company and Blue Rider Pictures

HANNIBAL CLASSICS PRESENTS A SPEED KILLS / HANNIBAL PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SABAN FILMS, THE PIMIENTA FILM COMPANY AND BLUE RIDER PICTURES JOHN TRAVOLTA SPEED KILLS KATHERYN WINNICK JENNIFER ESPOSITO MICHAEL WESTON JORDI MOLLA AMAURY NOLASCO MATTHEW MODINE With James Remar And Kellan Lutz Directed by Jodi Scurfield Story by Paul Castro and David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Screenplay by David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Based upon the book “Speed Kills” by Arthur J. Harris Produced by RICHARD RIONDA DEL CASTRO, pga LUILLO RUIZ OSCAR GENERALE Executive Producers PATRICIA EBERLE RENE BESSON CAM CANNON MOSHE DIAMANT LUIS A. REIFKOHL WALTER JOSTEN ALASTAIR BURLINGHAM CHARLIE DOMBECK WAYNE MARC GODFREY ROBERT JONES ANSON DOWNES LINDA FAVILA LINDSEY ROTH FAROUK HADEF JOE LEMMON MARTIN J. BARAB WILLIAM V. BROMILEY JR NESS SABAN SHANAN BECKER JAMAL SANNAN VLADIMIRE FERNANDES CLAITON FERNANDES EUZEBIO MUNHOZ JR. BALAN MELARKODE RANDALL EMMETT GEORGE FURLA GRACE COLLINS GUY GRIFFITHE ROBERT A. FERRETTI SILVIO SARDI “SPEED KILLS” SYNOPSIS When he is forced to suddenly retire from the construction business in the early 1960s, Ben Aronoff immediately leaves the harsh winters of New Jersey behind and settles his family in sunny Miami Beach, Florida. Once there, he falls in love with the intense sport of off-shore powerboat racing. He not only races boats and wins multiple championship, he builds the boats and sells them to high-powered clientele. But his long-established mob ties catch up with him when Meyer Lansky forces him to build boats for his drug-running operations. Ben lives a double life, rubbing shoulders with kings and politicians while at the same time laundering money for the mob through his legitimate business. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Newsletter Is Published by the College

Trinity Hall cover 2013_Trinity Hall cover 07/10/2013 08:51 Page 1 3 1 / 2 1 0 2 R A E Y C I M E D A C A R E T T E L S W E N L L A H Y T I N I R T The Trinity Hall Newsletter is published by the College. Newsletter Thanks are extended to all the contributors. ACADEMIC YEAR 2012/13 The Development and Alumni Office Trinity Hall, Cambridge CB2 1TJ Tel: +44 (0)1223 332562 Fax: +44 (0)1223 765157 Email: [email protected] www.trinhall.cam.ac.uk Return to contents www.trinhall.cam.ac.uk 1 Trinity Hall Newsletter ACADEMIC YEAR 2012/13 College Reports ............................................................................. 3 Trinity Hall Lectures .................................................................. 49 Student Activities, Societies & Sports ....................................... 89 Trinity Hall Association .......................................................... 109 The Gazette ...............................................................................115 Keeping in Touch ...................................................................... 129 Section One College Reports Return to contents www.trinhall.cam.ac.uk 3 From the Master The academic year 2012/13 closed with a sense of achievement and pride. The performance in the examinations was yet again outstanding: we finished third in the table of results, consolidating our position as one of the high achieving colleges in the College Reports University. This gratifying success was not the result of forcing the students into the libraries, laboratories and lecture theatres at the expense of other elements of life in College. Quite the contrary: one of the most pleasurable aspects of life in College at the moment is that students enjoy their academic work and find it a source of endless interest. -

Hope by the River

MAY 15, 2017 • Vol. 28 • No. 20 • $2 SERVING BERKS, LEHIGH, NORTHAMPTON & SURROUNDING COUNTIES www.LVB.com Do mergers HOPE BY THE RIVER of hospitals boost costs, inefficiency? By WENDY SOLOMON [email protected] The national and regional trend for hospital mergers continues unabated, but at least one expert who studies health care man- agement says larger hospital systems are inefficient and lead to higher costs and lower quality. Lawton Burns, professor of health ‘In each care management hospital that at the Wharton PHOTO/CHRISTOPHER HOLLAND School, University Developer Jerry McAward broke ground last month on a new outdoor recreation center at 123 Lehigh Drive along Sgt. Stanley Hoffman has joined Boulevard in Lehighton. of Pennsylvania, our network, told a gathering at Commerce could flow when massive outdoor center opens in Lehighton the Lehigh Valley we have Business Coalition been able to By CHRISTOPHER HOLLAND Drive, will replace biking excursions, river rafting, a kayak on Healthcare’s [email protected] the developer’s exist- school and eventually cross country ski recent annual con- significantly A new era in outdoor recreation is ing business in Jim rentals. Plus, for the first time, he will ference there is no reduce the about to begin in Lehighton, an era that Thorpe, at the same add a retail shop. academic evidence some say will draw thousands of people time dramatically “The addition of the outdoor center that hospital con- operating per week, trigger more commerce for expanding opera- will make the town an outdoor activity solidation improves expenses.’ other borough businesses and jump- tions and offerings magnet – in addition to Jim Thorpe and cost, efficiency or — Bob Martin, St.