Extract from Survivor from Titanic – Source a Daniel Buckley Was

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Titanic and the People on Board: a Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking Andrea Bijan Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History Spring 2014 Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking Andrea Bijan Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bijan, Andrea, "Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking" (2014). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 27. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/27 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Titanic and the People on Board: A Look at the Media Coverage of the Passengers After the Sinking By Andrea Bijan Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 4, 2014 Readers Professor Kimberly Jensen Professor David Doellinger Copyright © Andrea Bijan 2014 2 The Titanic was originally called the ship that was “unsinkable” and was considered the most luxurious liner of its time. Unfortunately on the night of April 14, 1912 the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank early the next morning, losing many lives. The loss of life made Titanic one of the worst maritime accident in history. Originally having over 2,200 passengers and crew on board only about 700 survived; most of the survivors being from the upper class. -

Mission Record Book, 1901-1940 Photograph by Frank Poole

Mission Record Book, 1901-1940 Photograph by Frank Poole Mission Record Books, 1901-1940 Photograph by Frank Poole THISTHI EXHIBITION endeavors to remember the efefforts of those who created the Irish Mission for ImmigrantImmig Girls in New York City. The story begins in IrelandIrelan with Charlotte Grace O’Brien’s inspiration and couragecoura to actually do something about the appalling emigrationemigr conditions she observed first-hand on the docksdocks in Queenstown. And, it continues with the commitmentcomm of the Catholic clergy and countless others to helphel over 100,000 women immigrants. The Mission RecordRecor Books on the emigration arrivals of the Irish womenwom are part of the collection of the Our Lady of thet Rosary, Saint Elizabeth Seton Shrine, at Watson House, and will be part of a planned future Irish heritage and genealogical center. PleaseP take a moment to sign our Guest Register and check our website: www.watsonhouse.org WeW invite your comments and when you are in NewN York encourage visits to the Irish Hunger Memorial,M a few blocks northwest at 290 Vesey StreetStr and North End Avenue, the Ellis Island ImmigrationImmi Museum, as well as other points of interestintere in Lower Manhattan. Mission Record Book, 1897 Photograph by Frank Poole CéadCéa míle fáilte isteach! “The sword of famine is less sparing than the bayonet of the soldier.” Thomas F. Meagher Irish patriot, part of the ‘Young Ireland’ 1848 rebellion and with William Smith O’Brien shipped to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), and distinguished American Civil War General The Great Irish Famine (1845-1852) did not initiate Irish immigration When an Irish girl left her family and home in Ireland, the Catholic to the United States – it institutionalized it. -

Chronology – Sinking of S.S. TITANIC Prepared By: David G

Chronology – Sinking of S.S. TITANIC Prepared By: David G. Brown © Copyright 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 by David G. Brown; All rights reserved including electronic storage and reproduction. Registered members of the Encyclopedia-Titanica web site may make a one (1) copy for their own use; and may reproduce short sections of this document in scholarly research articles at no cost, providing that credit is given to the “Brown Chronology.” All other use of this chronology without the expressed, written consent of David G. Brown, the copyright holder is strictly forbidden. Persons who use this chronology are expected to assist with corrections and updates to the material. Last Updated June 9, 2009 New York Time = Greenwich (GMT) – 5:00 Assumed April 14th Hours (Noon Long 44 30 W) Titanic = Greenwich – 2:58 Titanic = New York + 2:02 Assumed April 15th Hours (Noon Long 56 15 W) Titanic = Greenwich – 3:45 Titanic = New York + 1:15 Bridge Time (Bells) = Apri 14th Hours + 24 minutes; or, April 15th Hours - 23 minutes (Bridge time primarily served the seamen to allow keeping track of their watches by the ringing of ship’s bells every half hour.) CAUTION: Times Presented In This Chronology Are Approximations Made To The Best Of The Author’s Ability. Times Presented In This Chronology Have An Assumed Accuracy Range Of Plus-Or-Minus 10 Percent, or 6 Minutes either side of the time shown (total range 12 minutes). NOTES Colors of Type: BLACK – Indicates actions and events in the operation of the ship or the professional crew. -

Background Data Methods Results Methodological Peer-Review And

A finely stratified log-rank test with effectively-infinite-size comparison groups [ How long did their hearts go on? Survival analysis of the Titanic Survivors ] Background Erroneous analyses in longevity comparisons [Jazz Musicians, Oscar winners] Beyond "who survived": longterm effects Data Passengers ; Comparison Groups Methods Passengers: K-M curves Comparison Groups: "Cohort from Current" (U.S.) & Cohort(Sweden) Lifetables Results Overall; By Gender and Class Methodological Stratified log-rank test: each passenger versus effectively infinite comparison group Peer-review and beyond BMJ ; Media [email protected] http://www.epi.mcgill.ca CASI, May 17-19, 2006 Natural Sciences & Engineering Fonds Québécois de la recherche Research Council of Canada sur la nature et les technologies. Premature Death in Jazz Musicians: Fact or Fiction? commonly held view: More Statistical Study: 70 (82%) of 85 liable than other professions to US-born jazz musicians listed in die early from drink, drugs, university syllabus exceeded women, or overwork. their life expectancy Spencer FJ. Am J Public Health. 1991 81(6):804-5: Am J Public Health. 1992 82(5):761. Longevity of popes and artists between 13th & 19th century Likely, in past centuries, to be Longevity significantly longer better fed, clothed & sheltered, than that of artists (P = 0.02); ... and to had better medical care & artists had 1.5-fold higher risk of to survive longer than most of death before age 70 years than their contemporary people. Popes (95% CI: 1.08–2.16) Serraino D, Carrieri M-P: International Journal of Epidemiology 2005; 34: 1435–1436 Survival in Academy Award–Winning Actors and Actresses Social status is an important Life expectancy 3.9 years longer predictor of poor health. -

Titanic: Voices from the Disaster

******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* COVER FRONTISPIECE TITLE PAGE DEDICATION FOREWORD DIAGRAM OF THE SHIP CHAPTER ONE — Setting Sail CHAPTER TWO — A Floating Palace CHAPTER THREE — A Peaceful Sunday CHAPTER FOUR — “Iceberg Right Ahead.” CHAPTER FIVE — Impact! CHAPTER SIX — In the Radio Room: “It’s a CQD OM.” CHAPTER SEVEN — A Light in the Distance CHAPTER EIGHT — Women and Children First CHAPTER NINE — The Last Boats CHAPTER TEN — In the Water CHAPTER ELEVEN — “She’s Gone.” CHAPTER TWELVE — A Long, Cold Night CHAPTER THIRTEEN — Rescue at Dawn ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* CHAPTER FOURTEEN — Aftermath: The End of All Hope EPILOGUE — Discovering the Titanic GLOSSARY PEOPLE IN THIS BOOK OTHER FAMOUS TITANIC FIGURES SURVIVOR LETTERS FROM THE CARPATHIA TITANIC TIMELINE BE A TITANIC RESEARCHER: FIND OUT MORE TITANIC FACTS AND FIGURES FROM THE BRITISH WRECK COMMISSIONER’S FINAL REPORT, 1912 TITANIC: THE LIFEBOAT LAUNCHING SEQUENCE REEXAMINED TITANIC Statistics: Who Lived and Who Died SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY SOURCE NOTES PHOTO CREDITS INDEX ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR ALSO BY THIS AUTHOR COPYRIGHT ******ebook converter DEMO Watermarks******* (Preceding image) The wreck of the Titanic. At 2:20 a.m. on Monday, April 15, 1912, the RMS Titanic, on her glorious maiden voyage from Southampton to New York, sank after striking an iceberg in the North Atlantic, killing 1,496 men, women, and children. A total of 712 survivors escaped with their lives on twenty lifeboats that had room for 1,178 people. -

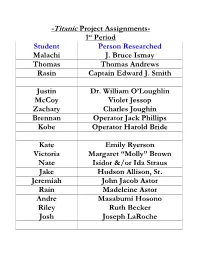

Titanic Project Assignments- 1St Period Student Person Researched Malachi J

-Titanic Project Assignments- 1st Period Student Person Researched Malachi J. Bruce Ismay Thomas Thomas Andrews Rasin Captain Edward J. Smith Justin Dr. William O’Loughlin McCoy Violet Jessop Zachary Charles Joughin Brennan Operator Jack Phillips Kobe Operator Harold Bride Kate Emily Ryerson Victoria Margaret “Molly” Brown Nate Isidor &/or Ida Straus Jake Hudson Allison, Sr. Jeremiah John Jacob Astor Rain Madeleine Astor Andre Masabumi Hosono Riley Ruth Becker Josh Joseph LaRoche Axel Frederick Goodwin Elliott Daniel Buckley Maddie Carla Jensen Kevin Olaus Abelseth Rocky 1st Officer William Murdoch Shani 2nd Officer Herbert Lightoller Dillon Quartermaster George Rowe Shawn Lookout Frederick Fleet Lisa Marian Thayer Michael John Thayer Annsley Charlotte Collyer Isabelly Bandmaster Wallace Hartley Gabby Selini “Celiney” Yazbeck Philip Zenni Kayli Alma Palsson Arabella Elsie Edith Bowerman Kayla Marie Young Helen Ostby Daisy Minahan Major Archibald Butt -Titanic Project Assignments- 2nd Period Student Person Researched Mauri J. Bruce Ismay Liam Thomas Andrews Charles Captain Edward J. Smith Basim Dr. William O’Loughlin Miriam Violet Jessop Asher Charles Joughin Carlos Operator Jack Phillips Shep Operator Harold Bride Karma Emily Ryerson Rhea Margaret “Molly” Brown Dazzetta Isidor &/or Ida Straus Taylor Hudson Allison, Sr. Sam John Jacob Astor Milele Madeleine Astor Drew Masabumi Hosono Yozmarie Ruth Becker Patrick Joseph LaRoche Brenden Frederick Goodwin Noah Daniel Buckley Aerial Carla Jensen Garrett Olaus Abelseth Andreas 1st Officer William Murdoch Matt 2nd Officer Herbert Lightoller Maddy Quartermaster George Rowe Abby Lookout Frederick Fleet Angelina Marian Thayer Duffy John Thayer Allyria Charlotte Collyer Hailey Bandmaster Wallace Hartley Yasmin Selini “Celiney” Yazbeck Naomi Philip Zenni Rebecca Alma Palsson Meadow Elsie Edith Bowerman Marie Young Helen Ostby Daisy Minahan Major Archibald Butt -Titanic Project Assignments- 5th Period Student Person Researched Erik J. -

Titanic Tim Vicary

Titanic Tim Vicary 1 Are these sentences true (T) or false (F)? c . makes plans that show people how to a ___ The Titanic was made in Northern make something. Ireland. d . is a person who works on a ship. b ___ All the passengers on the Titanic were e . is a person who sends messages. rich. 20 marks c ___ The Titanic went slower because there T were icebergs in the North Atlantic. 4 Put these sentences in the right order. TES d ___ Nobody saw the iceberg in front of the a ___ For 4 days, the passengers were happy. ship. b ___ An iceberg hit the side of the ship. e ___ Some people in the United States heard c ___ The Titanic went under the water. the Titanic’s first emergency message. d ___ The Titanic was made in 1912. COMPREHENSION f ___ All of the lifeboats were full. e ___ 711 of the Titanic’s passengers arrived g ___ The Titanic broke into two halves when in New York. it sank. f ___ The Carpathia arrived to help. h ___ The Californian was near the Titanic g ___ The Titanic went from Southampton. but it arrived too late to help. h ___ The Titanic’s radio operator sent the i ___ The 1997 film Titanic was all true. message ‘CQD’. j ___ Millvina Dean went under the sea to i ___ In 1985, some sailors saw the Titanic look at the Titanic. under the sea. 20 marks j ___ Water came into five compartments. 20 marks 2 Who said this? Benjamin Guggenheim, J. -

Titanic Tim Vicary

Titanic TIM VICARY BEFORE READING CHAPTER 7 Before Reading 1 N (There were not enough lifeboats for all the passengers.) ACTIVITY 1 BEFORE READING 2 N (It took more than two hours for the ship to 1 d sink.) 2 f 3 Y 3 e NSWERS 4 N (Some of the lifeboats go into the sea with room A 4 a for many more passengers.) 5 c 5 Y 6 b 6 N (Some third-class passengers broke the doors and ACTIVITY 2 BEFORE READING came up to the boat deck.) Open answers. CHAPTERS 7 AND 8 WHILE READING 1 How many lifeboats did the Titanic have? ACTIVITIES While Reading It had twenty lifeboats. 2 Why was Mrs Astor cold? CHAPTER 1 WHILE READING Because she did not have a warm coat. 1 halves, bottom 3 Why did Mrs Straus stay on the ship? 2 sailors, photographs Because she wanted to stay with her husband. 3 cameras, carefully 4 What did Daniel Buckley put on when he got into a 4 film, newspapers lifeboat? He put on a woman’s hat. CHAPTER 2 WHILE READING 1 F Thousands of people built the Titanic in Belfast. 5 How many musicians were there on the ship? 2 T There were eight musicians. 3 T 6 What kind of music did the musicians play? 4 F Astor’s wife Madeleine was eighteen years old. They played happy music. 5 F Edward Smith was the captain of the Titanic. 7 Why was it difficult to get into Lifeboat B? 6 F Most of the passengers were working people. -

“The Greatest Ship Ever Made” They Called It 'Unsinkable'

“The Greatest Ship Ever Made” They called it ‘Unsinkable’; the largest ship ever made with cutting edge- technology that would dominate any sea it chose to enter -The Titanic was truly considered to be the greatest ship ever made when it was sent on its maiden voyage in 1912. No-one could possibly have known what was to come, but what exactly was it about The Titanic that made it so special? The Ship itself White Star Line was the company that built the Titanic and was owned by J.P. Morgan, an American tycoon with a lot of huge amounts of money at his disposal. He would need it; the RMS Titanic would end up costing a monumental $7.5million when it was finally built. It took 3,000 men two years to build the Titanic with three million rivets being used to hold its massive hull together! Although there were 4 funnels (smoke stacks) that towered into the sky, only 3 were operational; the 4th funnel was merely for looks. The ship measured a huge 269 metres in length and 30 metres in width – it was comfortably the largest ship ever built. The Titanic was very expensive for ‘first-class’ travellers, the price of a single ticket was $4,700. (around $50,000 in 2016!) However, it was possible to travel on the vessel for a significantly lower amount if you were happy to go second or third class. The ship had a wide variety of things that made it stand out from other, lesser vessels. It had a Turkish Bath that travellers could bathe in, many restaurants of varying cuisines and even a gymnasium – a rarity in 1912. -

What Did the Survivors See of the Break-Up of the Titanic? by Bill Wormstedt

www.encyclopedia-titanica.org This article is copyright Encyclopedia Titanica and its licensors © 2003 It may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission. The Facts - What did the Survivors See of the Break-up of the Titanic? by Bill Wormstedt Up until 1985, when Bob Ballard discovered the wreck of the Titanic on the ocean floor, it was generally believed the Titanic sank intact, in one piece. Second Officer Lightoller, at the American and British Inquiries, and the books published by First-class passenger Colonel Gracie and Second-class passenger Lawrence Beesley, made statements to this effect immediately after the disaster, and this is what was accepted by the public for decades. Even now, 18 years after the discovery of the wreck, the 'general perception' is still that only a very few survivors claimed to see the ship split apart before she sank. But what are 'the facts'? What did the survivors really see, and how many *did* claim to see the ship break up? An examination of the texts of both the 1912 American and British Inquiries gives us a very good idea. (Many newspapers also printed accounts of what was seen, however attempting to find and bring together these very many articles is beyond the scope of this article. Also, a newspaper account may have been altered or exaggerated by a reporter, and it becomes hard to tell the exaggeration from what the witness actually saw and said.) All survivors interviewed by the Inquries will be examined below, with their own comments as to what they saw. -

A Night to Remember with a Foreword by Julian Fellowes and an Introduction by Brian Lavery

WALTER LORD A Night to Remember With a Foreword by Julian Fellowes and an Introduction by Brian Lavery PENGUIN BOOKS Contents Foreword by Julian Fellowes Introduction by Brian Lavery Preface 1 ‘Another Belfast Trip’ 2 ‘There’s Talk of an Iceberg, Ma’am’ 3 ‘God Himself Could Not Sink This Ship’ 4 ‘You Go and I’ll Stay a While’ 5 ‘I Believe She’s Gone, Hardy’ 6 ‘That’s the Way of It at This Kind of Time’ 7 ‘There is Your Beautiful Nightdress Gone’ 8 ‘It Reminds Me of a Bloomin’ Picnic’ 9 ‘We’re Going North Like Hell’ 10 ‘Go Away – We Have Just Seen Our Husbands Drown’ Facts about the Titanic Passenger List Illustrations Acknowledgements PENGUIN BOOKS A NIGHT TO REMEMBER ‘Absolutely gripping and unputdownable’ David McCullough, Pulitzer prize-winning author ‘Walter Lord singlehandedly revived interest in the Titanic … an electrifying book’ John Maxtone-Graham, maritime historian and author ‘A Night to Remember was a new kind of narrative history – quick, episodic, unsolemn. Its immense success inspired a film of the same name three years later’ Ian Jack, Guardian ‘Devotion, gallantry … Benjamin Guggenheim changing to evening clothes to meet death; Mrs Isador Straus clinging to her husband, refusing to get in a lifeboat; Arthur Ryerson giving his lifebelt to his wife’s maid … A book to remember’ Chicago Tribune ‘Seamless and skilful … it’s clear why this is many a researcher’s Titanic bible’ Entertainment Weekly ‘Enthralling from the first word to the last’ Atlantic Monthly ABOUT THE AUTHORS A graduate of Princeton University and Yale Law, Walter Lord served in England with the American Intelligence Service during the Second World War. -

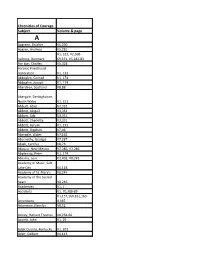

Chronicles of Courage Index

Chronicles of Courage Subject Volume & page A Aagreen, Brother V5,290 Aagren, Andreas V5,281 V1, 323, V2,368- Aalborg, Denmark 69,371, V5,282-83 Aar bon, Charles V5,328 Aaronic Priesthood restoration V1, 133 Abbeglen, Conrad V1, 174 Abbeglen, Joseph V1, 174 Aberdeen, Scotland V8,88 Abergale, Denbighshire, North Wales V1, 311 Abbott, Abiel V3,352 Abbott, Abigail V3,352 Abbott, Ada V3,351 Abbott, Charlotte V3,351 Abbott, Hyrum V1, 231 Abbott, Stephen V7,46 Abergale, Wales V7,162 Abernathy, Georgia V7,287 Abiah, Cynthia V8,76 Abiquiu, New Mexico V2,286, V2,286 Abplanalp, Peter V1, 174 Abrams, Levi V2,403, V8,242 Academy of Music, Salt Lake City V4,118, Academy of St. Mary's V8,245 Academy of the Sacred heart V8,246 Academies V1, 1 Accidents V1, 70,388-89 V1,157,160,161,163- Accordions 4,365 Ackerman, (family) V8,52 Ackley, Richard Thomas V8,258-66 Acomb, John V1, 29 Adair County, Kentucky V1, 201 Adair, Delbert V4,143 Adair, Elijan F V4,146 Adair, Eliza Ann V4,146 Adair, Ellen L. V4,147 Adair, G.W. V4,141 Adair, George V4,342 Adair, George Washington V4,145-47 Adair, John V6,226 Adair, Miriam B V4,133,141-43 Adair, Orson V4,142 Adair Spring V5,329 V2,15,131,179,340, Adam-ondi-Ahman V6,194 Adams, Annie V1, 180 Adams, Annie Asenath V4,102,103 Adams, B.L. V3,190 Adams, Barbara M V3,380 Adams, Barnabas L. V4,90,96 Adams, Barney V3,155 Adams County, Illinois V8,56 Adams, D.H.