Fulham Doctors of the Past *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hammersmith and Fulham by FCMS

Hammersmith and Fulham by FCMS Fire Risk Assessment of: 112-126 Walham Green Court Cedarne Rd Fulham London SW6 2DE Author of Assessment: M Richards GIFireE Quality Assured by: Yvonne Topping, Project Manager Responsible Person: Named person within the organisation, Richard Buckley Risk Assessment Valid From: 28/10/2020 Risk Assessment Valid To: 28/10/2022 Page: 1 of 12 Hammersmith and Fulham by FCMS Building Features Approximate Square Area of the Building: 400 Number of Dwellings: 15 Number of Internal Communal Stairs: 1 Number of External Escape Stairs: 2 Number of Final Exits: 2 Number of Storeys 7 Is there a Basement Present? Yes Is Gas Installed to Building? yes Are Solar Panels Installed on Building? no Number of Occupants: 45 Current Evacuation Policy: Stay Put Procedure Recommended Evacuation Policy: Stay Put Procedure Last LFB Inspection: Page: 2 of 12 Hammersmith and Fulham by FCMS Survey Findings: Building Construction & Purpose built medium rise block of brick on reinforced concrete forming part of Layout: the Walham Green development. The block is square of ground plus 6 upper levels and a flat roof. It has a single stair core and enclosed protected stair approach to the dwellings with one passenger lift opening into the accommodation area at each level between level 2 and 6. 3 flats per level to floors 3-6, 2 flats at level 2 and one at level 1. Also at ground level is the rear exit from the stair. Two separate retail units and undercroft car park entrance are also found at ground floor level which have no openings into the residential block. -

List of Applications for Week Ending 14 November 2020 ( Listed by Electoral Ward )

Wandsworth Borough Council Borough Planner's Service List of Applications for week ending 14 November 2020 ( Listed by electoral ward ) Balham Application No : 2020/3907 TEAM: E No of Neighbours Consulted: 0 Date Registered : 10 November 2020 Address : Audiology House, 45 Nightingale Lane SW12 8SU Proposal : Details of obscure screening pursuant to condition 14 of planning permission dated 15/10/2018 ref 2018/2949 (Demolition of the existing side and rear extensions of Audiology House and factory building to rear. Conversion of main Audiology House building including the erection of a three storey building to the rear, 2no. two storey extensions to main building to facilitate the conversion and redevelopment of the site to create 19 residential units (Use Class C3) with private and communal amenity space; associated car parking, cycle parking, landscaping and associated works.) Conservation area (if applicable): Applicant Agent Miss Emma Yu Frederick Gibberd Partnership 117-121 Curtain Road 117-121 Curtain Road London London EC2A 3AD EC2A 3AD United Kingdom Officer dealing with this application : Wendy Melaab On Telephone No : 020 8871 6136 Application No : 2020/4014 TEAM: E No of Neighbours Consulted: 6 Date Registered : 12 November 2020 Press Notice(s) Site Notice(s) Address : 87 A Thurleigh Road SW12 8TY Proposal : Alterations to existing outbuilding in connection with its conversion to a 1 x bedroom self contained residential unit; new roof with rooflights lights, new timber fencing and gate to Wroughton Road with associated refuse -

Hammersmith & Fulham Council

June 2020 Summary Report The full report and detailed maps: www.consultation.lgbce.org.uk www.lgbce.org.uk Our Recommendations Hammersmith & Fulham The table lists all the wards we are proposing as part of our final recommendations along with the number of voters in each ward. The table also shows the electoral variances for each of the proposed wards which tells you how we have delivered electoral equality. Finally, the table includes electorate projections for 2025 so you Council can see the impact of the recommendations for the future. Final Recommendations on the new electoral arrangements Ward Name Number of Electorate Number of Variance Electorate Number of Variance (2019) electors per from (2025) electors per from councillor average councillor average (%) (%) Addison 2 5,681 2,841 12% 5,936 2,968 5% Avonmore 2 5,315 2,658 5% 5,576 2,788 -1% Brook Green 2 5,811 2,906 15% 6,102 3,051 8% College Park & 3 5,855 1,952 -23% 8,881 2,960 5% Old Oak Coningham 3 7,779 2,593 2% 8,052 2,684 -5% Fulham Reach 3 8,359 2,786 10% 8,847 2,949 4% Fulham Town 2 5,312 2,656 5% 5,558 2,779 -2% Grove 2 5,193 2,597 3% 5,452 2,726 -3% Hammersmith 2 5,188 2,594 2% 5,468 2,734 -3% Broadway Who we are Why Hammersmith & Fulham? Lillie 2 4,695 2,348 -7% 5,619 2,810 0% ● The Local Government Boundary Commission ● The Commission has a legal duty to carry out an Munster 3 8,734 2,911 15% 9,027 3,009 7% for England is an independent body set up by electoral review of each council in England ‘from Palace & 3 8,181 2,727 8% 8,768 2,923 4% Parliament. -

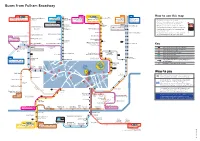

Buses from Fulham Broadway

Buses from Fulham Broadway 295 28 414 14 11 N11 Green Park towards Ladbroke Grove Sainsbury’s Shepherd’s Bush towards Kensal Rise Notting towards Maida Hill towards towards towards for Westeld from stops A, F, H Hill Gate Chippenham Road/ Russell Square Liverpool Street Liverpool Street from stops C, D, F, H Shirland Road Appold Street Appold Street from stops E, L, U, V N28 from stops E, L, U, V from stop R from stops B, E, J, R towards Camden Town Kensington Park Lane 211 Hyde Park Victoria SHEPHERD’S from stops A, F, H Church Street Corner towards High Street Waterloo BUSH Kensington Knightsbridge from stops B, E, J, L, U, V Harrods Buses from295 Fulham Broadway Victoria Coach Station Shepherd’s Bush Road KENSINGTON Brompton Road 306 HAMMERSMITH towards Acton Vale Hammersmith Library 28 N28 Victoria & Albert from stops A, F, H Museum Hammersmith Kensington 14 414 High Street 11 211 N11 295 Kings Mall 28 414 14 South Kensington 11 N11 Kensington Olympia Green Park Sloane Square towards Ladbroke GroveShopping Sainsbury’s Centre HammersmithShepherd’s Bush towards Kensal Rise Notting towards Maida Hill for Natural Historytowards and towards towards Busfor West Stationeld 306 from stops A, F, H Hill Gate Chippenham Road/ ScienceRussell Museums Square Liverpool Street Liverpool Street from stops C, D, F, H Shirland Road Appold Street Appold Street Hammersmith from stops E, L, U, V Hammersmith 211 Road N28 from stops E, L, U, V from stop R from stops B, E, J, R Town Hall from stops C, D, F, M, W towards Camden Town Park Lane 306 Kensington -

New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786–1808

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU History Faculty Publications History Winter 2008 New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786–1808 Isaac Land Indiana State University, [email protected] Andrew M. Schocket Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/hist_pub Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Land, Isaac and Schocket, Andrew M., "New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786–1808" (2008). History Faculty Publications. 5. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/hist_pub/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. New Approaches to the Founding of the Sierra Leone Colony, 1786–1808 Isaac Land Indiana State University Andrew M. Schocket Bowling Green State University This special issue of the Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History consists of a forum of innovative ways to consider and reappraise the founding of Britain’s Sierra Leone colony. It originated with a conversation among the two of us and Pamela Scully – all having research interests touching on Sierra Leone in that period – noting that the recent historical inquiry into the origins of this colony had begun to reach an important critical mass. Having long been dominated by a few seminal works, it has begun to attract interest from a number of scholars, both young and established, from around the globe.1 Accordingly, we set out to collect new, exemplary pieces that, taken together, present a variety of innovative theoretical, methodological, and topical approaches to Sierra Leone. -

Granville Sharp Pattison (1791-1851): Scottish Anatomist and Surgeon with a Propensity for Conflict

Pregledni rad Acta Med Hist Adriat 2015; 13(2);405-414 Review article UDK: 611-013“17/18“ 611 Pattison, S. G. GRANVILLE SHARP PATTISON (1791-1851): SCOTTISH ANATOMIST AND SURGEON WITH A PROPENSITY FOR CONFLICT GRANVILLE SHARP PATTISON (1791.–1851.): ŠKOTSKI ANATOM I KIRURG SKLON SUKOBIMA Anthony V. D’Antoni1, Marios Loukas2, Sue Black3, R. Shane Tubbs2-4 Summary Granville Sharp Pattison was a Scottish anatomist and surgeon who also taught in the United States. This character from the history of anatomy lived a very colourful life. As many are unaware of Pattison, the present review of his life, contributions, and controver- sies seemed appropriate. Although Pattison was known to be a good anatomist, he will be remembered for his association with a propensity for conflict both in Europe and the United States. Key words: anatomy; history; Scotland, surgery; Britain. 1 Department of Pathobiology, Sophie Davis School of Biomedical Education, The City College of New York of the City University of New York. 2 Department of Anatomy, St. George’s University, Grenada. 3 Centre of Anatomy and Human Identification, University of Dundee, U.K. 4 Seattle Science Foundation, Seattle, WA, USA. Corresponding author: R. Shane Tubbs. Pediatric Neurosurgery, Birmingham, AL, USA, Electronic address: [email protected] 405 Introduction Granville Sharp Pattison (1791-1851) was a Scottish anatomist and surgeon who taught medical practitioners in both Europe and the United States. Named after a British abolitionist, Pattison would become a controversial figure in both his personal and professional life. His reputation was so infa- mous that Sir William Osler referred to Pattison as “that vivacious and pug- nacious Scot.” Support of this description is found in the fact that Pattison kept a pair of pistols on his desk at all times (Desmond, 1988). -

Parsons Green Lane London Sw6 4Hu 6O/7O Prime Freehold Supermarket & Parsons Green Lane Restaurant Investment Opportunity London Sw6 4Hu 6O/7O

PARSONS GREEN LANE 6O/7O LONDON SW6 4HU PRIME FREEHOLD SUPERMARKET & RESTAURANT INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 6O/7O PARSONS GREEN LANE LONDON SW6 4HU 6O/7O PRIME FREEHOLD SUPERMARKET & PARSONS GREEN LANE RESTAURANT INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY LONDON SW6 4HU 6O/7O INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS Prime freehold supermarket and restaurant located in one of London’s most affluent boroughs Located approximately 50m south of Parsons Green Underground Station Attractive building with impressive street frontages comprising approximately 8,432 sq ft let to the Co-Operative Group Ltd and Le Pain Quotidien Ltd AWULT of approximately 12.9 years Approximately 53% of the income is secured to the Co-operative Group Ltd which benefits from RPI linked reviews for a further 17.5 years Current passing rent is £255,001 Freehold The most recent investment sale close by, let to Cote Restaurants Ltd, sold in April 2016 for a price reflecting 3.2% net initial yield Offers are sought in excess of £5,300,000 (Five Million Three Hundred Thousand Pounds) subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. This reflects a net initial yield of 4.5% after allowing for purchasers costs of 6.6%. 6O/7O IMPERIAL WHARF WANDSWORTH EEL BROOK FULHAM PUTNEY ROUNDABOUT COMMON BROADWAY BRIDGE CHELSEA UNDERGROUND HURLINGHAM PARSONS GREEN UNDERGROUND FOOTBALL CLUB STATION PARK UNDERGROUND STATION STATION 6O/7O PRIME FREEHOLD SUPERMARKET & PARSONS GREEN LANE RESTAURANT INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY LONDON SW6 4HU LOCATION Parsons Green is located in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, in South West London, and is one the most affluent areas within London. The area is centred at Parsons Green with Fulham Road A10 and New Kings Road to the north and south respectively STRATFORD providing access to Fulham to the north east and Putney to the south west. -

Literacy and the Humanizing Project in Olaudah Equiano's The

eSharp Issue 10: Orality and Literacy Literacy and the Humanizing Project in Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative and Ottobah Cugoano’s Thoughts and Sentiments Jeffrey Gunn (University of Glasgow) [A]ny history of slavery must be written in large part from the standpoint of the slave. (Richard Hofstadter, cited in Nichols 1971, p.403) The above statement suggests two sequential conclusions. The first implication is that the slave is in an authoritative position to present an authentic or alternative history of slavery beyond the ‘imperial gaze’ of Europeans (Murphy 1994, p.553). The second implication suggests that the act of writing empowers the slave. Literacy is the vehicle that enables the slave to determine his own self-image and administer control over the events he chooses to relate while writing himself into history. Throughout my paper I will argue that the act of writing becomes a humanizing process, as Olaudah Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano present a human image of the African slave, which illuminates the inherent contradictions of the slave trade.1 The slave narratives emerging in the late eighteenth century arose from an intersection of oral and literary cultural expressions and are evidence of the active role played by former black slaves in the drive towards the abolition of the African slave trade in the British Empire. Two of the most important slave narratives to surface are Olaudah Equiano’s The interesting narrative of the life of Olaudah 1 I will use the term ‘African’ to describe all black slaves in the African slave trade regardless of their geographical location. -

Newsletter 23-Aut 10

! No. 23 Autumn 2010 elcome to the latest edition of our newsletter. Our Historic Riverside As usual, the autumn issue contains a full Two of the oldest and most important historic areas in the W report of the Group’s activities over the past borough are Fulham Palace and its grounds (which year, including our events, which have been well originally included what is now Bishop’s Park) and the supported. The big news this year though is the Hammersmith Upper and Lower Malls. The latter contain publication of PPS 5 replacing PPG 15 and PPG 16. We a rich array of buildings dating from the 17th century, are grateful to have Michael Bussell to elucidate this many listed. Near the Dove pub on Upper Mall is a important new document for us. Elsewhere David Broad spectacular group of listed buildings, including Kelmscott tells the story of his suffragette great-grandmother, John House where William Morris lived and Sussex House, a Goodier spots the local ghosts of two City churches and Grade II* house dating from 1726 (see picture on p. 5). E the Archives look back to the Japan-British exhibition of Berry Webber’s splendid 1930s listed Hammersmith 1910 and a lost house off Wood Lane, now buried town hall looks across Furnivall Gardens to the river. beneath Westfield. There is good news for Fulham Palace and Bishop’s Park with the granting of the lottery application (see below). However, there is great anxiety about the threat to the Chairman’s Report historic Hammersmith riverside from the proposals for the town hall. -

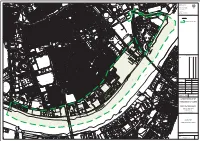

Map of the Sands End Conservation Area (PDF)

BSI D R E E R G IS TE FS 32265 Mu h arf Produced by Highways & Engineering on the Land Survey Mapping System. This drawing is Copyright. tation Refuse Tip (public) This map is reproduced from Ordnance Pumping Station Recycling Centre Survey material with the permission of the Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of 5 5 Her Majesty's Stationery Office. El 37 Sub 38 86 Sta 88 D A O R S Crown copyright T O Licence No.LA100019223 2006 L © 90 Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown 0 7 7 4 copyright and may lead to prosecution or 3 civil proceedings. L. B. HAMMERSMITH & FULHAM 6 1 to 15 9 Heatherley School of Electricity Ashburnham Fine Art 92 Electricity Generating Station Community Generating Station Centre Mud 3 LEGEND 2 FB 6 Adventure 6 Playground 9 Mean High Water Mud and Shingle Mud and Shingle Chelsea Creek MLW Chelsea Creek CONSERVATION AREA Chelsea Creek 1 16 Shingle Electricity Generating Station PH Car Park 114 AD O R TS LO Mud M ean High ater Wa Mean High W ter MLW Creek MLW Chelsea der Water ean Low High & M Mean ater igh W n H Mea Gas Holder Exhauster House 1 1 Gas Holder le Gas Holder g Mean High Water CHE n ra d 19 a 20 LS u 8 23 Q 4 EA HARB e to h T 1 17 Gas Works 2 30 OU 3 OOD TERRACE R 16 DRIV 2 rt 6 3 HARW 33 IMPE E 1 ou 46 T 0 RIA he C 18 al C L S Admira 1a ir QU Shingle 52 11 ARE ha m 8 m Carlyle Admiral Square Ad 3 bers 18 to 1 Court l Co l 1 9 2 6 S urt C 17 h ILLA 3 to elsea 5 1 H V 5 1 3 6 UG 3 H The Towpath RO 1 O arb 6 4 T RB 4 Laboratory 9 E E ou 1 THA ETE R MES AVEN P T S r D UE 7 L S N es 1 E Gas Holder -

2. Borough Transport Objectives

Chapter Two Objectives 2. Borough Transport Objectives 2.1 Introduction This chapter sets out Hammersmith & Fulham’s Borough Transport Objectives for the period 2011 - 2014 and beyond, reflecting the timeframe of the revised MTS. The structure is as follows: • Sections 2.2 and 2.5 describe the local context firstly providing an overview of the borough characteristics and its transport geography, and then summarising the London- wide, sub-regional and local policy influences which have informed the preparation of this LIP. • Section 2.6 sets out Hammersmith & Fulham’s problems, challenges and opportunities in the context of the Mayor’s transport goals and challenges for London, and looks at the main issues which need to be addressed within the borough in order to deliver the revised MTS goals. • Finally section 2.7 sets out our Borough Transport Objectives for this LIP, which have been created by the issues identified in Sections 2.2 to 2.6. 2.2 About Hammersmith & Fulham The borough of Hammersmith & Fulham is situated on the western edge of inner London in a strategic location on the transport routes between central London and Heathrow airport. The orientation of the borough is north to south, with most major transport links, both road and rail, carrying through-traffic from east to west across the borough. Some of the busiest road junctions in London are located in the borough at Hammersmith Broadway, Shepherds Bush Green and Savoy Circus and the borough suffers disproportionately from the effects of through-traffic. North-south transport links in the borough are not as good as east-west links. -

Teacher Trail 4 | Page 1

Teacher Trail 4 | Page 1 STAMFORD BRIDGE TO WALHAM GREEN Start at Stamford Bridge. Look at this photograph taken in 1927. 1a. Describe What has changed? What has stayed the same? The entrance to Chelsea Football The buildings in the photograph. Club. The bridge. The amount of traffic. What is the greatest change? Entrance to Chelsea football club. © Hammersmith & Fulham Urban Studies Centre Page 2 | Teacher Trail 4 Since 1995, there has been a lot of new building at Chelsea Football Club. 1b. Do you like the new buildings? YES NO 1c. Why? New stands. Chelsea Village, a leisure and entertainment complex with two four star hotels, a nightclub, five restaurants, health club, shops and business centre. Walk along Fulham Road past Holmead Road. © Hammersmith & Fulham Urban Studies Centre Teacher Trail 4 | Page 3 Find where this photograph was taken from. Fulham Road about 1955. 2a. How long ago was this? years ago. 2b. Describe any changes you can see. The road is much busier now. © Hammersmith & Fulham Urban Studies Centre Page 4 | Teacher Trail 4 Continue along Fulham Road to the Sir Oswald Stoll Foundation building. These flats were built for the families of men who fought in the First World War. 3a. When was the first World War? On the gate pillars are some of the famous battles of this war. 3b. Write down six of the battles which took place. Flats built 1917 - 1923. The Sir Oswald Stoll foundation established in 1916 to provide disabled veterans of the first world war (1914 -18) with affordable housing and medical help.