The Chotyniec Agglomeration and Its Importance for Interpretation of the So-Called Scythian Finds from South-Eastern Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gmina Sieniawa

WRZUCAMY NIE WRZUCAMY ✓ butelki plastikowe ◆ opakowania po lekach ✓ nakrętki, kapsle i zakrętki od słoików ◆ zużyte baterie i akumulatory ✓ plastikowe opakowania, torebki, ◆ puszki po farbach i lakierach worki foliowe ◆ folia aluminiowa ✓ opakowania wielomateriałowe (kartony po mleku/sokach) ✓ puszki po żywności ✓ opakowania po środkach czystości, kosmetykach METALE SZTUCZNE PAMIĘTAJ: wrzucaj czyste I TWORZYWA opakowania bez zawartości. WAŻNE: Zgniataj puszki, butelki i inne opakowania. ✓ butelki po napojach i żywności ◆ ceramika, doniczki, porcelana ✓ słoiki ◆ szkło okularowe i żaroodporne ✓ szklane opakowania po kosmetykach ◆ znicze ◆ żarówki, świetlówki i reflektory PAMIETAJ: wrzucaj opakowania ◆ opakowania po lekach, rozpuszczalni- szklane bez zawartości i nie tłucz kach i olejach silnikowych SZKŁO ich przed wrzuceniem. ◆ lustra i szyby ✓ opakowania z papieru i tektury ◆ odpady higieniczne np. ręczniki ✓ gazety, czasopisma, katalogi i ulotki papierowe i zużyte chusteczki ✓ zeszyty, książki ◆ kartony po mleku i napojach ✓ papier biurowy ◆ papier lakierowany i powleczony folią ◆ tłusty papier PAMIĘTAJ: usuń zszywki, metalowe ◆ papierowe worki po nawozach części i plastikowe elementy. i materiałach budowlanych HARMONOGRAM 2021 PAMIĘTAJ! Spalając papier niszczysz PAPIER ◆ tapety cenny surowiec. Posegregowany ◆ pieluchy jednorazowe ODBIORU ODPADÓW KOMUNALNYCH papier powinien trafić do procesu recyklingu. wraz z instrukcją ich segregacji Odpady kuchenne ◆ ziemia i kamienie ✓ odpadki warzywne i owocowe ◆ popiół z węgla kamiennego ✓ resztki -

4. Multinational Cultural Heritage in the Landscape of Contemporary Poland

Mariusz Kulesza* 4. MULTINATIONAL CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE LANDSCAPE OF CONTEMPORARY POLAND 4.1. Introduction Cultural heritage (patrimoine culturel) is a concept that has been expanding its range in recent years. It is considered to be an impor- tant factor in economic and social development, a means of search- ing for agreements in regions suffering from ethnic or religious conflicts and an expression of cultural diversity in various countries and regions all over the world. It is hard to disagree that respect for the past, the historical heritage, is one of the most important deter- minants of the level of culture of a society or a nation, the degree of its civilisation development. It has not only cultural and emotional dimensions, but also often translates into the concrete material ben- efits in the modern world. Even though the concept of cultural heritage was formulated more than 100 years ago, it has been greatly expanded over time, * Mariusz Kulesza – University of Łódź, Faculty of Geographical Sciences, De- partment of Political Geography and Regional Studies, Kopcińskiego 31, 90-142 Łódź, Poland, e-mail: [email protected] 114 Mariusz Kulesza gaining in importance in the last dozen years. Experts in the field note, that there are further objects that seem worth protecting, there is also the problem of selecting what the heritage includes, how to properly identify it and shape it so it becomes a memory of objects, qualities and places that reflect the widest possible social image. We need to remember that: “Cultural heritage is an object, an idea that originates in a specific reality, under certain conditions, based on historical principles of historical conditioning architectur- al and urban solutions. -

Stanowisko Krajowej Komisji Do Spraw Ocen Oddziaływania Na

STANOWISKO KRAJOWEJ KOMISJI DO SPRAW OCEN ODDZIAŁYWANIA NA ŚRODOWISKO W SPRAWIE PLANOWANYCH DZIAŁAŃ ZWIĄZANYCH Z REALIZACJĄ FARM WIATROWYCH W WOJEWÓDZTWIE PODKARPACKIM W dniu 17 lutego 2010 r. w Generalnej Dyrekcji Ochrony Środowiska odbyło się posiedzenie Krajowej Komisji do Spraw Ocen Oddziaływania na Środowisko pod przewodnictwem Pana prof. dr hab. inŜ. Andrzeja Jasińskiego, Zastępcy Przewodniczącego Krajowej Komisji. Przedmiotem spotkania była analiza dokumentacji dotyczącej oceny oddziaływania na środowisko planowanych w województwie podkarpackim działań związanych z realizacją farm wiatrowych. Ocenie poddane zostały zarówno prognozy oddziaływania na środowisko projektu miejscowego planu zagospodarowania przestrzennego oraz projektu studium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego gmin, jak i raporty dotyczące planowanych przedsięwzięć. I. Wprowadzenie Regionalny Dyrektor Ochrony Środowiska w Rzeszowie zwrócił się do Generalnego Dyrektora Ochrony Środowiska z prośbą o przedstawienie Krajowej Komisji do Spraw Ocen Oddziaływania na Środowisko kwestii związanych z planowanymi w województwie podkarpackim zamierzeniami, polegającymi na przygotowaniu i realizacji projektów z zakresu energetyki wiatrowej. Z uwagi na lokalizację oraz skalę planowanych działań, szczególnie w kontekście inwestycji juŜ zrealizowanych oraz projektowanych, które uzyskały juŜ niezbędne zezwolenia, realizacja następnych projektów wiąŜe się z moŜliwością wystąpienia znacząco negatywnego oddziaływania na środowisko, szczególnie wobec prawdopodobnych -

Strategia Rozwiązywania Problemów Społecznych Dla Gminy Radymno

STRATEGIA ROZWIĄZYWANIA PROBLEMÓW SPOŁECZNYCH DLA GMINY RADYMNO NA LATA 2016-2021 1 STRATEGIA ROZWIĄZYWANIA PROBLEMÓW SPOŁECZNYCH DLA GMINY RADYMNO NA LATA 2016-2021 SPIS TREŚCI WSTĘP 4 1. PODSTAWY PRAWNE W ZAKRESIE PLANOWANIA POLITYKI SPOŁECZNEJ W UNII EUROPEJSKIEJ 6 2. DOKUMENTY PROGRAMOWE POLITYKI SPOŁECZNEJ 7 3. OGÓLNA CHARAKTERYSTYKA GMINY RADYMNO 12 4. STRUKTURA DEMOGRAFICZNA 14 5. SYSTEM EDUKACJI 20 6. ZASOBY MIESZKANIOWE 24 7. BEZPIECZEŃSTWO PUBLICZNE 26 8. BEZROBOCIE 30 9. PRZEMOC W RODZINIE 33 10. PROBLEM ALKOHOLOWY 36 11. SYTUACJA OSÓB NIEPEŁNOSPRAWNYCH 39 12. WSPIERANIE RODZINY I SYSTEM PIECZY ZASTĘPCZEJ 46 13. POMOC SPOŁECZNA. ZAGROŻENIE MARGINALIZACJĄ I WYKLUCZENIEM SPOŁECZNYM 48 14. ZASOBY POMOCY SPOŁECZNEJ 56 15. PROGNOZA PROBLEMÓW SPOŁECZNYCH 60 16. PLANOWANIE SPOŁECZNE W STRATEGII ROZWIĄZYWANIA PROBLEMÓW SPOŁECZNYCH 64 17. METODA TWORZENIA GMINNEJ STRATEGII ROZWIĄZYWANIA PROBLEMÓW SPOŁECZNYCH 65 18. IDENTYFIKACJA CELU GENERALNEGO I PRIORYTETÓW 67 19. WSKAŹNIKI REALIZACJI CELÓW STRATEGICZNYCH 71 20. HARMONOGRAM, PODMIOTY ODPOWIEDZIALNE ZA REALIZACJE STRATEGII, ŹRÓDŁA FINANSOWANIA 75 21. RAMY FINANSOWANIA DZIAŁAŃ OKREŚLONYCH W STRATEGII ROZWIĄZYWANIA PROBLEMÓW SPOŁECZNYCH 80 22. SPIS TABEL 81 23. SPIS WYKRESÓW 83 24. SPIS MAP 83 2 STRATEGIA ROZWIĄZYWANIA PROBLEMÓW SPOŁECZNYCH DLA GMINY RADYMNO NA LATA 2016-2021 I CZĘŚĆ WSTĘPNA CZĘŚĆ WSTĘPNA ZAWIERA ELEMENTARNE INFORMACJE DOTYCZĄCE ZASAD KONSTRUOWANIA DOKUMENTU. PRZEDSTAWIONE W NIEJ ZOSTAŁY ASPEKTY PRAWNE, BĘDĄCE PODSTAWĄ DZIAŁANIA SAMORZĄDU LOKALNEGO, NA KTÓRYCH OPIERA -

Harmonogram Odbioru Odpadów Komunalnych Z Terenu Gminy Radymno W 2019 R

Harmonogram odbioru odpadów komunalnych z terenu Gminy Radymno w 2019 r. Zbiórka odpadów zmieszanych w poszczególnych miesiącach Lp. Miejscowość I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII OSTRÓW (od DK-4 do końca) 1 2 7 4 4 13 10 8 5 14 13 za 11 9 1 ZAMOJSCE, ZABŁOTCE 15 16 21 18 18 27 24 22 19 28 25 23 ( co drugi poniedziałek ) 29 30 2 1 KORCZOWA, ŁAZY, MOSZCZANY 8 5 5 14 11 9 6 3 12 10 2 16 15 ( co drugi wtorek) 22 19 19 28 25 23 20 17 26 24 30 29 2 3 OSTRÓW (od początku do DK-4) 10 7 7 4 13 11 8 5 14 12 3 16 17 (co drugi czwartek) 24 21 21 18 27 25 22 19 28 23 za 26 30 31 6 za 3 4 SKOŁOSZÓW 11 8 8 5 14 12 9 6 15 13 4 17 18 (co drugi piątek) 25 22 22 19 28 26 23 20 29 27 31 30 za 1.11 1 2 DUŃKOWICE, MŁYNY, PIASKI 14 11 11 8 6 3 12 9 7 4 5 15 16 (co drugi poniedziałek) 28 25 25 17 za 22 20 17 26 23 21 18 29 30 9 za 1 2 3 BUDZYŃ, ŚWIĘTE 12 12 9 7 4 13 10 8 5 6 15 16 17 (co drugi wtorek) 26 26 23 21 18 27 24 22 19 29 30 31 2 3 SOŚNICA 13 13 10 8 5 14 11 9 6 4 7 16 17 (co druga środa) 27 27 24 22 19 28 25 23 20 18 30 31 GRABOWIEC, MICHAŁÓWKA, 3 1 14 14 11 9 6 4 12 10 7 5 8 NIENOWICE, SOŚNICA-BRZEG 17 16 za 15 28 28 25 23 21 za 20 18 26 24 21 19 (co drugi czwartek) 31 29 CHOTYNIEC, CHAŁUPKI 1 2 CHOTYNIECKIE, ZAŁAZIE, ZALESKA 4 1 12 10 7 5 13 11 8 6 9 15 16 WOLA 18 15 26 24 21 19 27 25 22 20 29 30 (co drugi piątek) Wójt Gminy Radymno informuje, iż wywozem odpadów komunalnych w 2019 r. -

Dzielnicowi Komisariatu Policji W Radymnie

POLICJA PODKARPACKA https://podkarpacka.policja.gov.pl/rze/komendy-policji/kpp-jaroslaw/brak/75603,Dzielnicowi-Komisariatu-Policji-w-Radymnie.h tml 2021-09-29, 03:27 DZIELNICOWI KOMISARIATU POLICJI W RADYMNIE Komisariat Policji w Radymnie asp. szt. Wiesław Łyżeń tel. 47 824 15 21 e-mail: [email protected] Komisariat Policji w Radymnie obsługuje miasto i gminę Radymno, gminę Laszki. Interesanci przyjmowani są od poniedziałku do piątku w godz. 7.30-15.30. Dyżur całodobowy pełniony jest w KPP w Jarosławiu ul. Poniatowskiego 50, 37-500 Jarosław. Kontakt z dyżurnym Policji tel. 47 824 13 10, lub nr 997, 112. Dzielnicowi sierż. szt. Mateusz Szynal tel. 47 824 15 40 tel. kom. 572-908-545 e-mail: [email protected] UWAGA! Podany adres mailowy ułatwi Ci kontakt z dzielnicowym, ale nie służy do składania zawiadomienia o przestępstwie, wykroczeniu, petycji, wniosków ani skarg w rozumieniu przepisów. Dzielnicowy odbiera pocztę w godzinach swojej służby. W sprawach niecierpiących zwłoki zadzwoń pod nr 997 lub 112 lub (47 824 13 10). Radymno - ulice: Batorego, Bema, Budowlanych, Cicha, Grunwaldzka, Gruszki,Kilińskiego, J.Kochanowskiego, Kołłątaja, Kościuszki, Krasińskiego, Legionów, Lwowska od nr 1-70,3-go Maja,Mickiewicza, Nadbrzeżna, Narutowicza, Okrzei, Piaskowa, Piekarska, Piłsudskiego, Plażowa, Polna, Mikołaja Reja, Rejtana, Reymonta, Rybacka, Rynek, Sanowa, Sienkiewicza, Słoneczna, Słowackiego, Sobieskiego, Spisówka, Strażacka, Szopena, Zachariasiewicza,Zamknięta, Zasanie, Zarzecze, Zielona, Stefana Żeromskiego, Sportowa, Akacjowa, Dolna, Królowej Jadwigi, Jagodowa, Jana.Pawła II, Jesienna, Kasztanowa, Kolejowa, Letnia, Młynarska, Hanki Sawickiej Tysiąclecia, Wietrzna, Wiosenna, Wiśniowa, Zimowa, Złota Góra, osiedle Jagiełły Informacje dotyczące realizacji planu działania priorytetowego dla rejonu nr 1 mł. -

Harmonogram Odbioru Odpadów Komunalnych Z Terenu Gminy Radymno W 2018 R

Harmonogram odbioru odpadów komunalnych z terenu Gminy Radymno w 2018 r. Zbiórka odpadów zmieszanych w poszczególnych miesiącach Lp. Miejscowość I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII OSTRÓW (od DK-4 do końca) 4 za 2 1 8 5 5 14 11 9 6 3 12 10 1 ZAMOJSCE, ZABŁOTCE 16 15 22 19 19 28 25 23 20 17 26 24 ( co drugi poniedziałek ) 30 29 3 2 KORCZOWA, ŁAZY, MOSZCZANY 9 6 6 15 12 10 7 4 13 13 2 17 16 ( co drugi wtorek) 23 20 20 29 26 24 21 18 27 21 za 25 30 za 1.05 30 2 za 3 4 OSTRÓW (od początku do DK-4) 11 8 8 5 14 12 9 6 15 13 3 17 18 (co drugi czwartek) 25 22 22 19 28 26 23 20 29 27 30 za 31 31 za 1.11 1 2 SKOŁOSZÓW 12 9 9 6 4 13 10 7 5 14 4 15 16 (co drugi piątek) 26 23 23 20 18 27 24 21 19 28 29 30 5 za 1 2 3 DUŃKOWICE, MŁYNY, PIASKI 12 12 9 7 4 13 10 8 5 5 15 16 17 (co drugi poniedziałek) 26 26 23 21 18 27 24 22 19 29 30 31 2 3 BUDZYŃ, ŚWIĘTE 13 13 10 8 5 14 11 9 6 4 6 16 17 (co drugi wtorek) 27 27 24 22 19 28 25 23 20 18 30 31 3 1 SOŚNICA 14 14 11 9 6 4 12 10 7 5 7 17 17 za 15 (co druga środa) 28 28 25 23 20 18 26 24 21 19 31 29 GRABOWIEC, MICHAŁÓWKA, 1 2 4 1 12 10 7 5 13 11 8 6 8 NIENOWICE, SOŚNICA-BRZEG 15 16 18 15 26 24 21 19 27 25 22 20 (co drugi czwartek) 29 30 CHOTYNIEC, CHAŁUPKI 2 3 CHOTYNIECKIE, ZAŁAZIE, ZALESKA 5 2 13 11 8 6 14 12 9 7 9 16 17 WOLA 19 16 27 25 22 20 28 26 23 21 30 31 (co drugi piątek) Wójt Gminy Radymno informuje, iż wywozem odpadów komunalnych w 2018 r. -

Prognoza Oddziaływania Na Środowisko Strategii Rozwoju Powiatu Przeworskiego Na Lata 2014 – 2020

Prognoza oddziaływania na środowisko Strategii Rozwoju Powiatu Przeworskiego na lata 2014 – 2020 Opracowanie: „4ECO” Projektowanie w Ochronie Środowiska Maciej Majer 43-400 Cieszyn, ul. Ogrodowa 4 (Stowarzyszenie Wspierania Inicjatyw Gospodarczych DELTA PARTNER 43-400 Cieszyn, ul. Zamkowa 3A/1) Rzeszów, grudzień 2014 r. Prognoza oddziaływania dla Strategii Rozwoju Powiatu Przeworskiego na lata 2014-2020 Spis treści 1. Przedmiot opracowania .............................................................................................................. 7 2. Podstawy formalno–prawne opracowania ................................................................................. 8 3. Cel i zakres merytoryczny opracowania ................................................................................... 12 4. Metody pracy i materiały źródłowe .......................................................................................... 14 4.1. Wykorzystane materiały źródłowe .................................................................................... 14 4.2. Metoda opracowania ......................................................................................................... 15 5. Charakterystyka poszczególnych elementów środowiska przyrodniczego i ich powiązań ..... 17 5.1. Położenie, użytkowanie i zagospodarowanie terenu ....................................................... 17 5.2. Geomorfologia ................................................................................................................... 19 5.3. Budowa geologiczna -

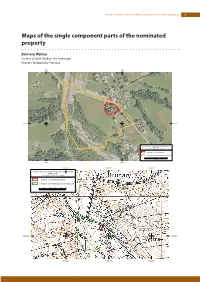

Maps of the Single Component Parts of the Nominated Property

WOODEN TSERKVAS OF THE CARPATHIAN REGION IN POLAND AND UKRAINE 9 Maps of the single component parts of the nominated property Brunary Wyżne Tserkva of Saint Michael the Archangel Poland / Małopolskie Province 21°01'40" 21°02'00" 49°32'00" 49°32'00" Wooden Tserkvas of Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine Brunary WyĪne Tserkva of St. Michael the Archangel boundary of the nominated property boundary of the nominated property's buffer zone 0306090120 Meters 21°01'40" 21°02'00" 21°01'40" 21°02'00" 21°02'20" Wooden Tserkvas of Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine Brunary WyĪne Tserkva of St. Michael the Archangel boundary of the nominated property boundary of the nominated property's buffer zone 0 50 100 150 200 250 Meters 49°32'00" 49°32'00" 21°01'40" 21°02'00" 21°02'20" 10 WOODEN TSERKVAS OF THE CARPATHIAN REGION IN POLAND AND UKRAINE Chotyniec Tserkva of the Birth of the Blessed Virgin Mary Poland / Podkarpackie Province 23°00'00" 23°00'20" 49°57'20" 49°57'20" Wooden Tserkvas of Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine Chotyniec Tserkva of the Brith of the Blessed Virgin Mary boundary of the nominated property boundary of the nominated property's buffer zone 49°57'00" 49°57'00" 0 25 50 75 100 125 Meters 23°00'00" 23°00'20" 22°59'40" 23°00'00" 23°00'20" Wooden Tserkvas of Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine Chotyniec Tserkva of the Brith of the Blessed Virgin Mary 49°57'20" 49°57'20" boundary of the nominated property boundary of the nominated property's buffer zone 0 40 80 120 160 200 Meters 49°57'00" 49°57'00" WOODEN TSERKVAS OF THE CARPATHIAN REGION IN POLAND AND UKRAINE 11 Drohobych Tserkva of Saint George Ukraine / Lviv Region 12 WOODEN TSERKVAS OF THE CARPATHIAN REGION IN POLAND AND UKRAINE Kwiatoń Tserkva of Saint Paraskeva Poland / Małopolskie Province 21°10'20" 21°10'40" 21°11'00" 49°30'00" 49°30'00" Wooden Tserkvas of Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine KwiatoĔ Tserkva of St. -

Unesco - World Heritage in Poland

UNESCO - WORLD HERITAGE IN POLAND Anna K Ola Cz Emilia S Auschwitz Birkenau Auschwitz was first constructed to hold Polish political prisoners, who began to arrive in May 1940. The first extermination of prisoners took place in September 1941, and Auschwitz Birkenau went on to become a major site of the Nazi Final Solution to the Jewish Question. From early 1942 until late 1944, transport trains delivered Jews to the camp's gas chambers from all over German-occupied Europe, where they were killed en masse with the pesticide Zyklon B. An estimated 1.3 million people were sent to the camp, of whom at least 1.1 million died. Around 90 percent of those killed were Jewish; approximately 1 in 6 Jews killed in the Holocaust died at the camp. Others deported to Auschwitz included 150,000 Poles, 23,000 Romani and Sinti, 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war, 400 Jehovah's Witnesses, and tens of thousands of others of diverse nationalities, including an unknown number of homosexuals. Many of those not killed in the gas chambers died of starvation, forced labor, infectious diseases, individual executions, and medical experiments. Castle of the Teutonic Order in Malbork Located in the Polish town of Malbork, is the largest castle in the world measured by land area.It was originally built by the Teutonic Knights, a German Roman Catholic religious order of crusaders, in a form of an Ordensburg fortress. The Order named it Marienburg(Mary's Castle). The town which grew around it was also named Marienburg. In 1466, both castle and town became part of Royal Prussia, a province of Poland. -

Streszczenie Raport A-4 Radymno-Korczowa 1 Sekcja Lipiec

Streszczenie raportu o oddziaływaniu na środowisko Autostrada A-4 Rzeszów – Korczowa na odcinku: Radymno (bez w ęzła) – Korczowa – długo ści 22 km (od km 647+455,82 do km 668+837,65) – zadanie II Sekcja 1 – od km 647+455,82 do km 664+300,00 SPIS TRE ŚCI 1. WST ĘP .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. CEL I ZAKRES OPRACOWANIA .................................................................................................................. 4 1.2. IDENTYFIKACJA PRZEDSI ĘWZI ĘCIA .......................................................................................................... 5 1.3. CEL REALIZACJI PRZEDSIĘWZI ĘCIA .......................................................................................................... 5 1.4. KWALIFIKACJA FORMALNA PRZEDSI ĘWZI ĘCIA ......................................................................................... 5 1.5. PODSTAWA OPRACOWANIA ...................................................................................................................... 6 1.6. PRZYJ ĘTE METODY OCENY , WSKAZANE TRUDNO ŚCI ................................................................................ 6 1.7. PRZEBIEG INWESTYCJI WZGL ĘDEM OBOWI ĄZUJ ĄCYCH DOKUMENTÓW PLANISTYCZNYCH ....................... 7 2. OPIS PRZEDSI ĘWZI ĘCIA I WARUNKI WYKORZYSTANIA TERENU W FAZIE BUDOWY I EKSPLOATACJI........................................................................................................................................................ -

POLAND UNESCO World Heritage Sites ISBN 978-83-8010-008-4

POLAND UNESCO World Heritage Sites ISBN 978-83-8010-008-4 www.poland.travel EN UNESCO Sites 1 UNESCO World Heritage Sites UNESCO Sites 3 Poland’s Contribution to the World’s Natural and Cultural Heritage Malbork Travelling across Poland can be an exceptional journey through unique treasures of history and nature. This country impresses with as many as fourteen out of nearly a thousand sites included Puszcza on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Toruń Białowieska Warszawa esides the historical centres of Kraków and Toruń attracting visitors with cen- Park Mużakowski Bturies-old buildings, there is also the Old Town in Warsaw. Poland’s capital city moved Wrocław UNESCO experts because of its scale of recon- Jawor struction work that was unprecedented in the Zamość Świdnica history of humankind. A medieval castle in Tarnowskie Góry Radruż Malbork is also included on the prestigious list. Kraków Chotyniec It is the world’s largest building made of brick. Auschwitz-Birkenau Binarowa Wieliczka Poland attracts visitors with extraordinary gar- Kalwaria Zebrzydowska Bochnia Owczary Blizne Brunary Lipnica Murowana Haczów dens, the most valuable wooden temples, church- Wy żne Sękowa Dębno Podhalańskie Kwiatoń Turzańsk es and tserkvas – testimony to the artistry of old Powroźnik Smolnik craftsmen and religious sites still bustling with life. The country is proud of a ground-break- Baltic Coast, Warmia and Masuria ing work of architecture – the Centennial Hall Central and Eastern Poland in Wrocław. The Auschwitz-Birkenau German Southern Poland Nazi Concentration and Extermination Camp (1940-1945) is a very special site. Białowieża Lower Silesia and Wielkopolska Forest is a complex of primeval forests which is unique in the whole of Europe.