Rebooting an Old Script by New Means: Teledildonics—The Technological Return to the ‘Coital Imperative’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shari Cohn Sex Addiction Brochure

Shari Cohn Chat Rooms…Cybersex… Online Affairs… MSSW, LCSW, SC How many people CSAT-Certified Sex Cyber Romance… have problems with Addiction Therapist Internet Sex… Cybersex? Online Pornography… Helping Individuals, Estimates are that about 15% of people in the Couples and Families Recover United States - men and women - using the Harmless Fun? Or A Internet for sexual purposes have problems From Internet Serious Problem For You with their cybersex activities. Sex Addiction Or Someone You Know? About 9 million of these users are sexually • addicted and another 15 million use cybersex in Therapy for Internet Sex Addiction/Cybersex Addiction risky ways and show signs of compulsivity. • Therapy for Partners/Spouses and Some of these cybersex users were already Families of Sex Addicts having preexisting problems with sex addiction before they went on the Internet for sexual Research based, focused therapy helps purposes, but for others their Internet sexual people who are struggling with sexual activity was the first time they showed any addiction and compulsivity to develop the life Shari Cohn signs of sexual addiction. competencies to be successful in recovery. MSSW, LCSW, SC, CSAT Seventy percent of all Internet adult content Support and services for spouses/partners Certified Sex Addiction Therapist sites are visited during the 9-5 workday. and families of sex addicts are critical to assist healing from the negative Internet sex is very powerful and potentially consequences of sex addiction. very destructive. The comparison has been made that cybersex is like the crack cocaine of In my Certified Sex Addiction Therapist the Internet. training, I was taught by Dr. -

Sexuality Education for Mid and Later Life

Peggy Brick and Jan Lunquist New Expectations Sexuality Education for Mid and Later Life THE AUTHORS Peggy Brick, M.Ed., is a sexuality education consultant currently providing training workshops for professionals and classes for older adults on sexuality and aging. She has trained thousands of educators and health care professionals nationwide, is the author of over 40 articles on sexuality education, and was formerly chair of the Board of the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS). Jan Lunquist, M.A., is the vice president of education for Planned Parenthood Centers of West Michigan. She is certified as a sexuality educator by the American Association of Sex Educators, Counselors, and Therapists. She is also a certified family life educator and a Michigan licensed counselor. During the past 29 years, she has designed and delivered hundreds of learning experiences related to the life-affirming gift of sexuality. Cover design by Alan Barnett, Inc. Printing by McNaughton & Gunn Copyright 2003. Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036-7802. Phone: 212/819-9770. Fax: 212/819-9776. E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.siecus.org 2 New Expectations This manual is dedicated to the memory of Richard Cross, M.D. 1915-2003 “What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender before Nana came to tidy the room. “Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?” “Real isn’t how you are made,” said the Skin Horse. -

An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans in ICT Environments Volume 9, Number 1, May 2013 DOI

ISSN: 1795-6889 Volume 9, Number 1, May 2013 Volume 1, Number 2, October 2005 Päivi HäkkinenM, Editorarja Kankaanranta, in Chief Editor An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans in ICT Environments Volume 9, Number 1, May 2013 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.201501071029 Contents From the Editor in Chief: Evolving Technologies for a Variety of pp. 1–3 Human Practices Päivi Häkkinen Original Articles Creative Network Communities in the Translocal Space of Digital Networks pp. 4–21 Rasa Smite Telepresence and Sexuality: A Review and a Call to Scholars pp. 22–55 Matthew Lombard and Matthew T. Jones Evidence Against a Correlation Between Ease of Use and Actual Use pp. 56–71 of a Device in a Walk-in Virtual Environment Tarja Tiainen, Taina Kaapu, and Asko Ellman Designing a Multichannel Map Service Concept pp. 72–91 Hanna-Marika Halkosaari, L. Tiina Sarjakoski, Salu Ylirisku, and Tapani Sarjakoski Effects of Positioning Aids on Understanding the Relationship Between pp. 92–108 a Mobile Map and the Environment Juho Kässi, Christina M. Krause, Janne Kovanen, and L. Tiina Sarjakoski Human Technology: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans in ICT Environments Editor in Chief Human Technology is an interdisciplinary, scholarly Päivi Häkkinen, University of Jyväskylä, Finland journal that presents innovative, peer-reviewed articles exploring the issues and challenges Board of Editors surrounding human-technology interaction and the Jóse Cañas, University of Granada, Spain human role in all areas of our ICT-infused societies. Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Technical University Munich, Germany Human Technology is published by the Agora Center, Jim McGuigan, Loughborough University, United University of Jyväskylä and distributed without a Kingdom charge online. -

Theescapist 064.Pdf

Do I think it worked? Somewhat. and visual have been improving, becoming next sense to involve. Plus, the tactile Certainly, during the demonstrations, more and more realistic, so much so that nature gives a feeling of doing, rather people got very into the fights – they we’ve pretty much reached a point of than just watching. It makes the game Fighting with a broadsword is hard. First cheered and crowd favorites were diminishing returns, when comparing more of an experience, and isn’t there’s all the trouble of swinging a large chosen. Afterward, we got tons of financial input to visual and audio output. experience what it’s all about? steel object around with one hand, much questions: How heavy is the sword? In addition, we’ve reached a point where less one that requires two hands. And Quite. Isn’t it hard to move in the many of the games’ offerings outclass the Cheers, then add on top of this the trouble of armor? It is. Did you know that sparks hardware on the gamers’ end – graphics armor; whether you use chain mail flew from the swords? Yep. Can I have a are now only as good as a player’s HDTV, (which is silly heavy) or you use leather picture with you? Um, sure. People were if he even has one. (lighter, but a little more stiff) you just getting that this wasn’t something that really don’t know the extent to which was something you could walk off the Where does that leave us when we are until you’ve been there. -

2010 Catalog

y s a t n Fa ur Yo or F For Your Pleasure, Inc. 49 Vose Farm Road, Unit 110 Peterborough, NH 03458 FOR YOUR PLEASURE (603) 925-4397 2010 – 2011 Party Collection www.foryourpleasure.com [email protected] $3.50 About For Your Pleasure, Inc. This is an adult oriented catalog. It is not intended for minors. For Your Pleasure® began as Rainbow Resource, a New Hampshire All items in this catalog are sold as Adult Novelties only. It is the customer’s obligation to check local and state laws based company providing online and mail-order products to the adult before ordering. There is a $25.00 fee for all non-suffi cient community. Due to increasing requests for an intimate setting for fund payments. Per person shipping & handling fees are demonstrating products, lotions, novelties, etc., the wholesale home party $5.95 if shipped to a Host/Hostess with a complete show division was born. For Your Pleasure® began calling the home parties… and $8.95 if shipped individually to the customer. Exception: For Your Pleasure Parties. In 1999 For Your Pleasure® developed it’s (Canada, Alaska, Puerto Rico, APO’s and US Virgin Islands streamlined Party Plan and did away with lugging the store. This provided need to add $8.95 per person for orders shipped with a complete show to a hostess and $15.95 for individual a Work Smarter…Not Harder atmosphere for the Independent Business shipping of order). There is a 20% restocking fee on all Associates affiliated with FYP. refused orders and a $10.00 fee plus shipping for reship Charmaine Bennett, Founder, has consistently aligned For Your Pleasure for all returned shipments to FYP. -

75491 • 10Th Volume • Monthly Publication • 03 / 2016 • HOSTS of the EROTIX Awards 2016 • Strictly for Adults Only

EAN_03-16_01_Titel_EAN_00-10_01_Titel.qxd 26.02.16 14:16 Seite 1 75491 • 10th volume • monthly publication • 03 / 2016 • HOSTS OF THE EROTIX AWARDs 2016 • strictly for adults only Official media cooperation partner Feature Interview Interview Industry survey about the future of Justin Santos (Joybear Pictures) New at Nexus: Kerri Middleton eroFame page 46 page 66 page 84 EAN_03-16_02-05_Inhalt_Layout 1 26.02.16 14:19 Seite 1 EAN_03-16_02-05_Inhalt_Layout 1 26.02.16 14:19 Seite 2 CONTENT letter from the editor News: International Business News 08 Dear Ladies and Gentlemen Feature: Some of you may already have heard that the Is 2016 the year of male toys? 44 eroFame Global Trade Convention has prepared a survey to decide the future direction of the event. To Feature: Fiera Arouser for Her 48 that end, you will find a questionnaire added to this edition of EAN, giving you an opportunity to express Interview: your suggestions and wishes. Of course, you can also Wieland Hofmeister (eroFame) 50 answer the questionnaire online, for instance on the Interview: EAN Facebook page or the eroFame Facebook Manuel Martin (Lingox) 56 page. But what is this whole hubbub about? Primarily, it is about the location of eroFame. Some industry Interview: members feel that Hanover is not the perfect place Angela Lieben (Liberator) 62 for the show anymore, or they feel that another city Interview: might attract more members of the international Justin Santos (Joybear) 66 trade. Of course, eroFame has responded to these suggestions, offering several options to its exhibitors Interview: and visitors. Now it is up to the producers, distributors, Django Marecaux (Vitenza) 72 wholesalers, and retailers to decide whether the show Interview: will stay in Hanover, whether it will take place in a Miguel Capilla (Fleshlight) 78 different European metropolis once every three years, or whether the show will move to a new location Interview: altogether. -

Cyber Sex Guide to Sexual Health, Risk Awareness, Pleasure, and Well-Being

Safe(r) sexting Cyber Sex nudes online Guide work- self- shops made porn phone sex sex- camming sexy video calls Online sexual activities are part of the sexual repertoire of many people. Follow the Safe(r) Cyber Sex Guide to sexual health, risk awareness, pleasure, and well-being. The most common way of having safe(r) cybersex is to involve people you know personally and trust. FIRST THINGS FIRST • What are my intentions and expectations? Is it just fantasy play? What happens afterwards? • Do I feel comfortable showing and sharing sexual content? • Do I want to incorporate cybersex into my sexual repertoire? • Who do I want to ask for a cybersex date and under which circumstances? • Is it possible to check in with your cybersex partner(s), receive emotional aftercare, and exchange feedback afterwards? • Am I prepared to accept "No” as a possible answer? Do I feel like my “Yes / No” and expressions of concern will be heard? DATA PROTECTION • What do I want to protect and from whom? • Am I confident to take the risk of being identifiable by showing my face, piercings, tattoos, scars, birthmarks, my hair, or my home furniture? • Can I keep my background blurry or neutral? • Have I kept my real name and location private? • Do I know the people involved personally? Whether yes or no: Do I feel comfortable having cybersex with them? • Have we talked about boundaries, terms and conditions? Who should be allowed to see and have access to sexual content or images? The most efective way to protect your intimacy is to make sure you are not identifiable. -

Consensual Nonmonogamy: When Is It Right for Your Clients?

Consensual Nonmonogamy: When Is It Right for Your Clients? By Margaret Nichols Psychotherapy Networker January/February 2018 You’ve been seeing the couple sitting across from you for a little more than six months. They’ve had a sexless marriage for many years, and Joyce, the wife, is at the end of her rope. Her husband, Alex, has little or no sex drive. There’s no medical reason for this; he’s just never really been interested in sex. After years of feeling neglected, Joyce recently had an aair, with Alex’s blessing. This experience convinced her that she could no longer live without sex, so when the aair ended, the marriage was in crisis. “I love Alex,” Joyce said, “but now that I know what it’s like to be desired by someone, not to mention how good sex is, I’m not willing to give it up for the rest of my life.” Divorce would’ve been the straightforward solution, except that, aside from the issue of sex, they both agree they have a loving, meaningful, and satisfying life together as coparents, best friends, and members of a large community of friends and neighbors. They want to stay together, but after six months of failed therapeutic interventions, including sensate-focus exercises and Gottman-method interventions to break perpetual-problem gridlock, they’re at the point of separating. As their therapist, what do you do? • Help them consciously uncouple • Refer them to an EFT therapist to help them further explore their attachment issues • Advise a temporary separation, reasoning that with some space apart they can work on their sexual problems • Suggest they consider polyamory and help them accept Alex’s asexuality. -

Running Head: COMMUNICATION in POLYAMOROUS RELATIONSHIPS 1

Running head: COMMUNICATION IN POLYAMOROUS RELATIONSHIPS 1 How Communication is Used in Polyamorous Relationships Meghan Wallace A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Counselling City University of Seattle 2019 APPROVED BY Colin James Sanders, MA, RCC, PhD, Advisor, Counselling Psychology Faculty Christopher Kinman, MA, RCC, PhD (Candidate), Faculty Reader, Counselling Psychology Faculty Division of Arts and Sciences COMMUNICATION IN POLYAMOROUS RELATIONSHIPS 2 A Phenomenological Study of the Use of Communication to Maintain a Polyamorous Relationship Meghan Wallace City University of Seattle COMMUNICATION IN POLYAMOROUS RELATIONSHIPS 3 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................. 3 Abstract................................................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 Nature of the Study .......................................................................................................................7 Scholarly Context .........................................................................................................................8 Definitions ................................................................................................................................. -

The Infidelity Online Workbook

The Infidelity Online Workbook: An Effective Guide to Rebuild Your Relationship After a Cyberaffair Dr. Kimberly S. Young Director Center for Online Addiction _____________________________________________________________________________________ Copyright The Center for On-Line Addiction, P.O. Box 72, Bradford, PA 16701 http://netaddiction.com 1 1998 The Center for On-Line Addiction DEFINING VIRTUAL ADULTERY Is cybersex cheating? One must first ask, “How is adultery morally defined?” Bill Clinton would first need to know what we mean by the word “is”. Joking aside, the real issue here is how do we define infidelity. “Adultery is adultery, even if its virtual” according to Famiglia Cristiana (Christian Family), a magazine close to the Vatican. “It is just as sinful as the real thing.” The question of the morality of flirting, falling in love and perhaps betraying a spouse via the World Wide Web surfaced in the advice column of the June, 2000 issue of Italy’s largest-circulation newsweekly 1. Adultery is often based upon moral judgments rather than factual information, independently formed through social conventions, religious teachings, family upbringing, reading books, and life experiences. So before anyone can answer the question, “is cybersex cheating”, we need to first define what is meant by the term adultery and what constitutes “sex” outside of marriage? We all argue about where to draw the line. In my travels, I have found that there are levels of adultery with certain sexual acts being considered acceptable to do within a marriage while others are clearly not. For some people, flirting is acceptable but actual kissing and touching are wrong. -

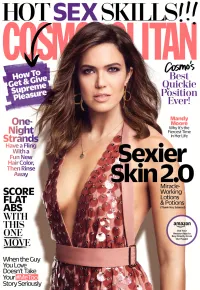

Cosmo-Le-Wand-Mar18-The-Future-Of

SEX THE future I’m sitting in the brightly lit offices of global OF sex-toy brand Fun Factory on what I hear is a rare sunny day in Bremen, Germany. Alina Eynck, 23, the was founded in 1996 by As a result, the $15 company’s newest (and two guys making dildos billion adult-toy biz is youngest) designer, is out of Play-Doh in their quickly morphing from graciously walking me kitchens.) “Men aren’t a male-dominated through the process using these products empire to an even more sex of how she designed Mr. themselves, so I don’t valuable vulva- pleasing, Boss ($95, funfactory think there’s been a lot of women-for-women HOW YOU ( ( CAN HELP .com)—a vibrator that’s thought on how the toys industry. “The demand curved specifically to interact with women’s for better products, accu- SHAPE THE stimulate a woman’s bodies or what makes rate content, and educa- FUTURE G-spot. I nod in approval us feel sexy.” That’s why tion has created a huge as she describes how she many vibes focus on two change,” explains Meika Your voice got the size, shape, things—penetration or Hollender, cofounder and as a consumer of arousing and flexibility just right. shaking hard (aka what co-CEO of the sexual- accessories Then Eynck’s boss, a man assumes feels wellness brand Sustain is a powerful Simone Kalz, 44, amazing to a woman)— Natural and author of the force…and one shows me her latest cre- and why a lot of them are new book Get on Top. -

Sexcams in a Dollhouse: Social Reproduction and the Platform Economy

Sexcams in a Dollhouse: Social Reproduction and the Platform Economy Antonia Hernández A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfllment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada July 2020 © Antonia Hernández, 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Antonia Hernandez-Salamovich Entitled: Sexcams in a Dollhouse: Social Reproduction and the Platform Economy and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy (Communication) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Richard Lachapelle External Examiner Dr. Geert Lovink External to Program Dr. Johanne Sloan Examiner Dr. Fenwick McKelvey Examiner Dr. Mark Sussman Thesis Co-Supervisor Dr. Kim Sawchuk Approved by Dr. Krista Lynes, Graduate Program Director August 25, 2020 _____________________________________________ Dr. Pascale Sicotte, Dean Faculty of Arts and Science iii ABSTRACT Sexcams in a Dollhouse: Social Reproduction and the Platform Economy Antonia Hernández, Ph. D. Concordia University, 2020 Once a peripheral phenomenon on the Web, sexcam platforms have been gaining social and eco- nomic importance, attracting millions of visitors every day. Crucial to this popularity is the tech- nical and economic model that some of those sites use. Sexcam platforms combine the practices of labor and user-generated platforms. As platforms, they mediate between users and providers, becoming the feld where those operations occur. Sexcam platforms, however, are more than inter- mediaries, and their structures incorporate and reproduce discriminatory conventions.