In This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999/6 Layout

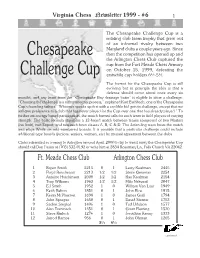

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

FM ALISA MELEKHINA Is Currently Balancing Her Law and Chess Careers. Inside, She Interviews Three Other Lifelong Chess Players Wrestling with a Similar Dilemma

NAKAMURA WINS GIBRALTAR / SO FINISHES SECOND AT TATA STEEL APRIL 2015 Career Crossroads FM ALISA MELEKHINA is currently balancing her law and chess careers. Inside, she interviews three other lifelong chess players wrestling with a similar dilemma. IFC_Layout 1 3/11/2015 6:02 PM Page 1 OIFC_pg1_Layout 1 3/11/2015 7:11 PM Page 1 World’s biggest open tournament! 43rd annual WORLD OPEN Hyatt Regency Crystal City, near D.C. 9rounds,June30-July5,July1-5,2-5or3-5 $210,000 Guaranteed Prizes! Master class prizes raised by $10,000 GM & IM norms possible, mixed doubles prizes, GM lectures & analysis! VISIT OUR NATION’S CAPITAL SPECIAL FEATURES! 4) Provisional (under 26 games) prize The World Open completes a three 1) Schedule options. 5-day is most limits in U2000 & below. year run in the Washington area before popular, 4-day and 3-day save time & 5) Unrated not allowed in U1200 returning to Philadelphia in 2016. money.New,leisurely6-dayhas three1- though U1800;$1000 limit in U2000. $99 rooms, valet parking $6 (if full, round days. Open plays 5-day only. 6) Mixed Doubles: $3000-1500-700- about $7-15 nearby), free airport shuttle. 2) GM & IM norms possible in Open. 500-300 for male/female teams. Fr e e s hutt l e to DC Metro, minutes NOTECHANGE:Mas ters can now play for 7) International 6/26-30: FIDE norms from Washington’s historic attractions! both norms & large class prizes! possible, warm up for main event. Als o 8sections:Open,U2200,U2000, 3) Prize limit $2000 if post-event manyside events. -

Sample Pages

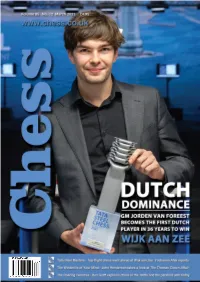

01-01 Cover -March 2021_Layout 1 17/02/2021 17:19 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/02/2021 09:47 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial....................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcolm Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...Jorden van Foreest.......................................................7 Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine We catch up with the man of the moment after Wijk aan Zee Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Website: www.chess.co.uk Dutch Dominance.................................................................................................8 The Tata Steel Masters went ahead. Yochanan Afek reports Subscription Rates: United Kingdom How Good is Your Chess?..............................................................................18 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 Daniel King presents one of the games of Wijk,Wojtaszek-Caruana 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 3 year (36 issues) £125 Up in the Air ........................................................................................................21 Europe There’s been drama aplenty in the Champions Chess Tour 1 year (12 issues) £60 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Howell’s Hastings Haul ...................................................................................24 3 year (36 issues) £165 David Howell ran -

Bulletin Round 6 -08.08.14

Bulletin Round 6 -08.08.14 That Carlsen black magic Blitz and “Media chess attention playing is a tool to seals get people to chess” Photos: Daniel Skog, COT 2014 (Carlsen and Seals) / David Martinez, chess24 (Gelfand) Chess Olympiad Tromsø 2014 – Bulletin Round 6– 08.08.14 Fabiano Caruana and Magnus Carlsen before the start of round 6 Photo: David Llada / COT2014 That Carlsen black magic Norway 1 entertained the home fans with a clean 3-1 over Italy, and with Magnus Carlsen performing some of his patented minimalist magic to defeat a major rival. GM Kjetil Lie put the Norwegians ahead with the kind of robust aggression typical of his best form on board four, and the teams traded wins on boards two and three. All eyes were fixed on the Caruana-Carlsen clash, where Magnus presumably pulled off an opening surprise by adopting the offbeat variation that he himself had faced as White against Nikola Djukic of Montenegro in round three. By GM Jonathan Tisdall Caruana appeared to gain a small but comfortable Caruana is number 3 in the world and someone advantage in a queenless middlegame, but as I've lost against a few times, so it feels incredibly Carlsen has shown so many times before, the good to beat him. quieter the position, the deadlier he is. In typically hypnotic fashion, the position steadily swung On top board Azerbaijan continues to set the Carlsen's way, and suddenly all of White's pawns pace, clinching another match victory thanks to were falling like overripe fruit. Carlsen's pleasure two wins with the white pieces, Mamedyarov with today's work was obvious, as he stopped to beating Jobava in a bare-knuckle brawl, and with high-five colleague Jon Ludvig Hammer on his GM Rauf Mamedov nailing GM Gaioz Nigalidze way into the NRK TV studio. -

SHMS-64 Nuevo Campeón Ruso Por Equipos El SHMS-64 Se Impuso En

SHMS-64 nuevo campeón ruso por equipos El SHMS-64 se impuso en el Campeonato Absoluto por Equipos, o Premier, celebrado del 12 al 23 de abril, en Olginka, Krasnodar. El torneo sigue siendo la prueba de clubes más fuerte del mundo, aunque este año tuvo varios equipos más débiles que lo habitual; participaron 12 equipos de 6 tableros titulares y dos suplentes; había cinco equipos aspirantes al primer lugar. El SHMS-64 (2.704 puntos de Elo Promedio), logró 20 puntos, fruto de 9 triunfos y 2 empates, estuvo integrado por Boris Gelfand (ISR), Wang Hao (CHI), Fabiano Caruana (ITA, 8 puntos de 10, 2852 de rating performance ), Anish Giri (NED), Alexander Riazantsev (RUS), Vladimir Potkin (RUS), Boris Grachev (RUS), y el otro puntal junto a Caruana, Evgeniy Najer (RUS, 8½ de 10 y 2.801 de rating performance ) Con la misma puntuación finalizó el Tomsk–400, con 2.686 de Elo Promedio, fue superado por sólo medio punto de desempate, estuvo compuesto por Ruslan Ponomariov (UKR, 7½ de 10 y 2.828 de rating performance ), Alexander Motylev (RUS, 7½ de 10 y 2.800 de rating performance ), Alexander Areshchenko (RUS), Ernesto Inarkiev (RUS), Viktor Bologan (MOL), Denis Khismatullin (RUS) y el jugador de mejor rendimiento del torneo, Igor Kurnosov, (RUS, 8 ½ de 9 y 2.893 de rating performance ) En términos individuales los mejores fueron, además de los citados, el ruso Alexey Dreev con 2.837 de rating performance . En el 12º Campeonato Ruso Femenino, que tuvo 8 equipos, el empate en el primer puesto fue triple, entre el SHSM–RSCU, que se impuso por tercer desempate, el Giprorechtrans y el ABC. -

Learning Long-Term Chess Strategies from Databases

Mach Learn (2006) 63:329–340 DOI 10.1007/s10994-006-6747-7 TECHNICAL NOTE Learning long-term chess strategies from databases Aleksander Sadikov · Ivan Bratko Received: March 10, 2005 / Revised: December 14, 2005 / Accepted: December 21, 2005 / Published online: 28 March 2006 Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2006 Abstract We propose an approach to the learning of long-term plans for playing chess endgames. We assume that a computer-generated database for an endgame is available, such as the king and rook vs. king, or king and queen vs. king and rook endgame. For each position in the endgame, the database gives the “value” of the position in terms of the minimum number of moves needed by the stronger side to win given that both sides play optimally. We propose a method for automatically dividing the endgame into stages characterised by different objectives of play. For each stage of such a game plan, a stage- specific evaluation function is induced, to be used by minimax search when playing the endgame. We aim at learning playing strategies that give good insight into the principles of playing specific endgames. Games played by these strategies should resemble human expert’s play in achieving goals and subgoals reliably, but not necessarily as quickly as possible. Keywords Machine learning . Computer chess . Long-term Strategy . Chess endgames . Chess databases 1. Introduction The standard approach used in chess playing programs relies on the minimax principle, efficiently implemented by alpha-beta algorithm, plus a heuristic evaluation function. This approach has proved to work particularly well in situations in which short-term tactics are prevalent, when evaluation function can easily recognise within the search horizon the con- sequences of good or bad moves. -

NEWSLETTER 158 (May 29, 2014)

NEWSLETTER 158 (May 29, 2014) ECU PRESIDENT SILVIO DANAILOV MEETS WITH THE PRESIDENT OF THE ITALIAN CHESS FEDERATION, MR. GIANPIETRO PAGNONCELLI On 21st of May, 2014 in Milan, the ECU President Silvio Danailov met with the Presidеnt of the Italian Chess Federation, Mr. Gianpietro Pagnoncelli. In a pleasant conversation at the office of the Italian Chess Federation they discussed the work done by Silvio Danailov and his team during the last 4 years. Silvio Danailov expressed his special thanks to Mr. Pagnoncelli for his great contribution in mobilization of the Italian members of the European Parliament during the campaign for adoption of the ECU program “Chess in School”. As we have already informed you the Italian MEP, Mr. Mario Mauro, was among the most active deputies, who supported the efforts of Mr. Danailov. Both Presidents discussed also the new joint project between ECU and UNESCO, “Chess as UNESCO intangible world heritage”. Silvio Danailov proposed one member of the commission, which will be responsible for this topic, to be elected by the Italian Chess Federation. Mr. Pagnoncelli said that this will be decided on the next ICF Board meeting. ECU President congrtulated Mr. Gianpietro Pagnoncelli for his sucessful 10-year career as President of the Italian Chess Federation, at the beginning of which Italy had just 2 grandmasters. Now ICF can be proud with 11 GMs, one of them, Fabiano Caruana is currently No 5 in the world. Silvio Danailov congratulated Mr. Pagnoncelli also for the acceptance of the ICF for a member of the Italian Olympic Committee rightly aloud. This achievement happened for the first time in the history of chess. -

British Knockout: Adams, Howell, Jones & Mcshane

PRESS RELEASE For immediate release BRITISH KNOCKOUT: ADAMS, HOWELL, JONES & MCSHANE INTO SEMIS England top 4 Mickey Adams, David Howell, Gawain Jones and Luke McShane all negotiate their way through a tough quarter-final stage to qualify for the British Knockout Championship semi-finals. David Howell triumphs eventually over IM Ravi Haria in a rapid playoff, despite almost coming to grief in the first Classical game. Semi-Finals pit Adams vs McShane and Howell vs Jones. Live coverage of the Semi-Final matches, starting Tuesday at 11:00 UTC, is available on the London Chess Classic website. LONDON (December 10, 2018) – Despite valiant efforts from the underdogs in the British Knockout, England Olympiad team members Mickey Adams, David Howell, Gawain Jones and Luke McShane all managed to win their Quarter-Final matches – although not without a struggle. Qtr Fina1 1 1 2 3 4 A Simon Williams 2466 ½ 0 - - - ½ Mickey Adams 2706 ½ 1 - - - 1½ Qtr Fina1 2 1 2 3 4 A David Howell 2697 ½ ½ 1 1 - 3 Ravi Haria 2436 ½ ½ 0 0 - 1 Qtr Fina1 3 1 2 3 4 A Gawain Jones 2683 1 ½ - - - 1½ Alan Merry 2429 0 ½ - - - ½ Qtr Fina1 4 1 2 3 4 A Jonathan Hawkins 2579 ½ 0 - - - ½ Luke McShane 2667 ½ 1 - - - 1½ David Howell had the closest shave of all the top seeds, only managing to qualify for the Semi-Finals after winning a nail-biting playoff match 2-0 against IM Ravi Haria. Elsewhere, Mickey Adams enjoyed a convincing victory in Game 2 of his match, after putting GM Simon Williams’s central king position under pressure in a double-edged Sicilian Richter-Rauzer. -

On March 30, 2010, Mozambique Issued 6 Stamps (Scott: 1993) That

On March 30, 2010, Mozambique issued 6 stamps (Scott: 1993) that pays tribute to the following chess players: Garry Kasparov, Vasily Smyslov, Anatoly Karpov, Viswanathan Anand, Bobby Fischer and Veselin Topalov. Vladimir Kramnik is featured in the sheet selvage. On March 30, 2010, Mozambique issued a souvenir sheet (Scott: 1993) with a single high denomination stamp, which pays tribute to chess great Vasily Smyslov (1921-2010). On March 30, 2010, Mozambique issued 6 stamps (Scott: 1992) which features the following female chess champions: Antoaneta Stefanova, Pia Cramling, Viktorija Cmilyte, Xu Yuhua, Alexandra Kosteniuk, Judit Polgar and, in the sheet selvage, Zhu Chen. On March 30, 2010, Mozambique issued a souvenir sheet (Scott: 2019) which features chess champion Alexandra Kosteniuk on the high denomination stamp and, in the sheet selvage, Zhu Chen. In 2010, Bulgaria issued a souvenir sheet commemorating the Anand-Topalov match. In 2010, Georgia issued a chess stamp. (Michel 586) In 2010, Nagormo-Karabakh issued stamps on children’s books, one including chess. In 2010, Togo issued 2 chess stamps. (Michel 3629/3+B) In 2010, Nepal issued its first chess commemorative cover and postmark, commemorating the 1st Lalitpur Cup International Open Rating Chess Tournament in July, 2010. On November 30, 2010, Mozambique issued 4 stamps (Scott: 2105) that paid tribute to Vasily Smyslov (1921-2010). On November 30, 2010, Mozambique issued a souvenir sheet (Scott: 2117) in tribute to Vasily Smyslov (1921-2010). In 2010, Lithuania issued a commemorative chess stamp in honor of Vladas Mikenas (1910- 1992). He was an International Master and chess journalist. In 2010, Armenia issued a stamp depicting Henrik Kasparyan and correspondence chess. -

Rapport D'activités 2015/2016

RAPPORT D’ACTIVITE 2015-2016 Rapport annuel d’activité 2015/2016 de la Ligue Corse des Echecs Lega Corsa di Scacchi- Ligue Corse des Echecs Tél 04 95 31 59 15 2, rue du Commandant Lherminier www.corse-echecs.corsica Télécopie 04 95 32 52 42 20200 Bastia [email protected] Table des matières Table des matières PRESENTATION ET BILAN DE L’ANNÉE _________________________________________ 1 AFFILIATIONS ET LICENCES __________________________________________________ 5 ORGANISATION ET STRUCTURE _____________________________________________ 18 COMPETITIONS SPORTIVES _________________________________________________ 24 COMMUNICATION ET PUBLICATION ___________________________________________ 62 ACTIVITES INSTITUTIONNELLES DE LA LIGUE __________________________________ 69 PRESENCE DE LA LIGUE AU SEIN DE LA SOCIETE INSULAIRE ____________________ 72 PRESENCE DE LA LIGUE SUR LA SCENE NATIONALE ET INTERNATIONALE _________ 81 LA FORMATION ____________________________________________________________ 86 ELITE ET COMPETITION : A SCOLA DI L’ECCELLENZA ___________________________ 95 LES ECHECS EN MILIEU SCOLAIRE __________________________________________ 118 LES EVENEMENTIELS DE LA LIGUE __________________________________________ 149 CONTACTS : LE BUREAU ___________________________________________________ 179 INFORMATIONS SUR L’ASSOCIATION ________________________________________ 179 Pg. 01 Rapport annuel d’activité 2015/2016 de la Ligue Corse des Echecs PRESENTATION ET BILAN DE L’ANNÉE Depuis sa création en 1998, la Ligue Corse s'investit pour développer les échecs sur tout le territoire. Elle compte aurd’hui plus de 7 900 affiliés dont la grande majoritée sont des jeunes de moins de 16 ans. Il y a en Corse 45 000 jeunes de 6 à 21 ans qui savent jouer aux échecs. La Ligue Corse est engagée dans une démarche moderne qui s'appuie sur les vertus socio-éducatives des Échecs. Elle est pour un élargissement considérable de la base de la pyramide échiquéenne. -

Kasparov's Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM

California Chess Journal Volume 20, Number 2 April 1st 2004 $4.50 Kasparov’s Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM Scrambles to Build 25 Deep Blues! Past Vs Future Special Issue • Young Fischer Fires Up S.F. • Fischer commentates 4 Boyscouts • Building your “Super Computer” • Building Fischer’s Dream House • Raise $500 playing chess! • Fischer Articles Galore! California Chess Journal Table of Con tents 2004 Cal Chess Scholastic Championships The annual scholastic tourney finishes in Santa Clara.......................................................3 FISCHER AND THE DEEP BLUE Editor: Eric Hicks Contributors: Daren Dillinger A miracle has happened in the Phillipines!......................................................................4 FM Eric Schiller IM John Donaldson Why Every Chess Player Needs a Computer Photographers: Richard Shorman Some titles speak for themselves......................................................................................5 Historical Consul: Kerry Lawless Founding Editor: Hans Poschmann Building Your Chess Dream Machine Some helpful hints when shopping for a silicon chess opponent........................................6 CalChess Board Young Fischer in San Francisco 1957 A complet accounting of an untold story that happened here in the bay area...................12 President: Elizabeth Shaughnessy Vice-President: Josh Bowman 1957 Fischer Game Spotlight Treasurer: Richard Peterson One game from the tournament commentated move by move.........................................16 Members at -

Armenia Gana El Campeonato Mundial De Ajedrez Por Equipos

Image not found or type unknown www.juventudrebelde.cu Image not found or type unknown Levon Aronian, número tres del ranking mundial, defendió el primer tablero de Armenia. Autor: FIDE Publicado: 21/09/2017 | 05:02 pm Armenia gana el campeonato mundial de ajedrez por equipos Los armenios, monarcas olímpicos en 2006 y 2008, volvieron por sus fueros en este torneo que reunió a las mejores selecciones del orbe en Ningbo, China Publicado: Miércoles 27 julio 2011 | 10:43:08 am. Publicado por: Juventud Rebelde Un empate frente a Ucrania en la última ronda le bastó a los armenios para ganar invictos con 14 puntos el campeonato mundial de ajedrez por equipos, que concluyó este martes en Ningbo, China. El evento reunió a nueve de las diez primeras selecciones del ranking universal y solo faltó Francia (número tres del escalafón), cuyo lugar fue ocupado por Egipto (45). Con un remate de cuatro victorias en las últimas cuatro rondas, China ocupó el segundo lugar con 13 unidades, seguida por Ucrania (12). Así se completó el podio. Mientras, el favorito equipo de Rusia cayó a la cuarta plaza con diez puntos, tras su derrota final frente a la escuadra india (perdieron Nepomniachtchi y Svidler). Hungría y Estados Unidos se ubicaron a continuación con el mismo acumulado. Después finalizaron Azerbaiján (nueve rayas), India (7), Israel (5) y Egipto (0), por ese orden. Individualmente, el Gran Maestro chino Wang Hao (2718) se llevó la medalla de oro en el primer tablero y su compatriota Wang Yue (2709) reinó en el segundo. Los restantes premios fueron para el ruso Ian Nepomniachtchi (2711) en la tercera mesa y el ucraniano Alexander Areshchenko (2682) en la cuarta.