Do Bad Boys Finish First? an Investigation of a Lay Theory of Heterosexual Women's Mate Preferences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of English Taboo Words in Movie Bad Boys 2

AN ANALYSIS OF ENGLISH TABOO WORDS IN MOVIE BAD BOYS 2 SKRIPSI Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Pendidikan (S.Pd) English Education Program By: DINA AULIANI NPM : 1602050019 FACULTY OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF NORTH SUMATERA 2020 ABSTRACT Auliani, Dina. 1602050019. “An Analysis of English Taboo Words in Movie Bad Boy 2”. Skripsi: English Education Program of Faculty Teacher Training and Education, University of Muhammadiyah Sumatera Utara. Medan. 2020 The research with the types and function of taboo words in movie Bad Boys 2. The objectives of the research was to analyze the type and function of taboo words in movie Bad Boys 2. The data were analyzed by identifying types and function taboo words in movie Bad Boys 2 taken from the script of dialogues Bad Boys 2. This study used descriptive qualitative method. All taboo words consisted of ephitet, obscenity, vulgarity and profanity appeared in the movie. The four kinds of taboo words applied in movie Bad Boys 2 were the total words taboo in the movie were 32, ephitets were 7 (22%), propanity were 12 (37%), vulgarity were 5 (16%), and obscenity were 8 times (25%). The most dominant kinds of taboo words used in movie Bad Boys 2 were propanity with 12 (37%). There were four functions of taboo words applied in movie Bad Boys 2. The total function of taboo words were 32, to show contempt was 17 (53%), to draw attention to oneself was 8 appeared (25%), to be provocative was 5 appeared (16%) and to muck authority with 2 appeared (6%). -

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide Represents the Most Requested Songs at Weddings and Parties

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide represents the most requested songs at Weddings and Parties. Please circle songs you like and cross out the ones you don’t. You can also write-in additional requests on the back page! WEDDING SONGS ALL TIME PARTY FAVORITES CEREMONY MUSIC CELEBRATION THE TWIST HERE COMES THE BRIDE WE’RE HAVIN’ A PARTY SHOUT GOOD FEELIN’ HOLIDAY THE WEDDING MARCH IN THE MOOD YMCA FATHER OF THE BRIDE OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL BACK IN TIME INTRODUCTION MUSIC IT TAKES TWO STAYIN ALIVE ST. ELMOS FIRE, A NIGHT TO REMEMBER, RUNAROUND SUE MEN IN BLACK WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU RAPPERS DELIGHT GET READY FOR THIS, HERE COMES THE BRIDE BROWN EYED GIRL MAMBO #5 (DISCO VERSION), ROCKY THEME, LOVE & GETTIN’ JIGGY WITH IT LIVIN, LA VIDA LOCA MARRIAGE, JEFFERSONS THEME, BANG BANG EVERYBODY DANCE NOW WE LIKE TO PARTY OH WHAT A NIGHT HOT IN HERE BRIDE WITH FATHER DADDY’S LITTLE GIRL, I LOVED HER FIRST, DADDY’S HANDS, FATHER’S EYES, BUTTERFLY GROUP DANCES KISSES, HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY, HERO, I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, IF I COULD WRITE A SONG, CHICKEN DANCE ALLEY CAT CONGA LINE ELECTRIC SLIDE MORE, ONE IN A MILLION, THROUGH THE HANDS UP HOKEY POKEY YEARS, TIME IN A BOTTLE, UNFORGETTABLE, NEW YORK NEW YORK WALTZ WIND BENEATH MY WINGS, YOU LIGHT UP MY TANGO YMCA LIFE, YOU’RE THE INSPIRATION LINDY MAMBO #5BAD GROOM WITH MOTHER CUPID SHUFFLE STROLL YOU RAISE ME UP, TIMES OF MY LIFE, SPECIAL DOLLAR WINE DANCE MACERENA ANGEL, HOLDING BACK THE YEARS, YOU AND CHA CHA SLIDE COTTON EYED JOE ME AGAINST THE WORLD, CLOSE TO YOU, MR. -

Growing up in Confinement in Twentyfirst Century Memoirs And

Closet Children: Growing Up in Confinement in TwentyFirst Century Memoirs and Fiction XiaoFang Chi s1046209 25 June 2015 Word count: 19,557 MA Thesis Literary Studies: English Literature and Culture Leiden University Supervisor and first reader: Dr. Michael Newton Second reader: Prof. dr. Peter Liebregts ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to examine cases and stories about children who grew up in confinement. I will explore the importance of attachment in the cases of children who grew up in captivity, and the socioemotional aspects of what it means to be human, by analysing their narratives. Through our cultural obsession with these children, we must not forget the trauma they have endured and by listening to their voices we can better understand their trauma and possible ways to heal from it. Firstly, I will be looking at some notable and historical cases of children who grew up in confinement. Through these cases, I explore some of the devastating effects a life of confinement can have on children, such as the trauma and developmental delay it causes. Next, I will analyze two memoirs by kidnap victims: 3,096 Days (2010) by Natascha Kampusch and A Stolen Life: A Memoir (2011) by Jaycee Dugard. I will look at the healing effect of trauma narratives and investigate the fascination of readers with this genre. Lastly, I will analyze two novels about growing up in confinement, Room (2010) by Emma Donoghue and The Boy from the Basement (2006) by Susan Shaw, and explore the reading they can offer as works of fiction. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

End Of Year Charts 1995 CHART #1995000 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Gangsta's Paradise In The Summertime No Need To Argue Tuesday Night Music Club 1 Coolio 21 Shaggy 1 The Cranberries 21 Sheryl Crow Last week 0 / 0 weeks MCA/BMG Last week 0 / 0 weeks VIRGIN Last week 0 / 0 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 0 / 0 weeks A&M/POLYGRAM Waterfalls Scream Cracked Rear View Frog Stomp 2 TLC 22 Michael Jackson 2 Hootie & The Blowfish 22 Silverchair Last week 0 / 0 weeks BMG Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks WARNER Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Boombastic One Sweet Day Forrest Gump OST Bizarre Fruit 3 Shaggy 23 Mariah Carey & Boyz II Men 3 Various 23 M People Last week 0 / 0 weeks VIRGIN Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks BMG Fantasy U Will Know Dookie Daydream 4 Mariah Carey 24 BMU 4 Green Day 24 Mariah Carey Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks POLYGRAM Last week 0 / 0 weeks WARNER Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Cotton Eye Joe I Can Love You Like That History: Purple 5 Rednex 25 All 4 One 5 Michael Jackson 25 Stone Temple Pilots Last week 0 / 0 weeks BMG Last week 0 / 0 weeks WARNER Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks WARNER How Deep Is Your Love Runaway The Colour Of My Love Greatest Hits 6 Portrait 26 Janet Jackson 6 Celine Dion 26 Bruce Springsteen Last week 0 / 0 weeks EMI Last week 0 / 0 weeks MERCURY/POLYGRAM Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY Last week 0 / 0 weeks SONY I've Got A Little Something For You Have You Ever Really Loved A Wom.. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

How America Went Haywire

Have Smartphones Why Women Bully Destroyed a Each Other at Work Generation? p. 58 BY OLGA KHAZAN Conspiracy Theories. Fake News. Magical Thinking. How America Went Haywire By Kurt Andersen The Rise of the Violent Left Jane Austen Is Everything The Whitest Music Ever John le Carré Goes SEPTEMBER 2017 Back Into the Cold THEATLANTIC.COM 0917_Cover [Print].indd 1 7/19/2017 1:57:09 PM TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 CODE: FILE: DESCRIPTION: 29A-008875-25C-PBC-17-238F.indd PBC-17-238F TAKE A BREAK BEFORE TAKING ONTHEWORLD ABREAKBEFORETAKING TAKE PUB/POST: The Atlantic -9/17issue(Due TheAtlantic SAP #: #: WORKORDER PRODUCTION: AP.AP PBC.17020.K.011 AP.AP al_stacked_l_18in_wide_cmyk.psd Art: D.Hanson AP17006A_003C_EarlyCheckIn_SWOP3.tif 008875 BLEED: TRIM: LIVE: (CMYK; 3881 ppi; Up toDate) (CMYK; 3881ppi;Up 15.25” x10” 15.75”x10.5” 16”x10.75” (CMYK; 908 ppi; Up toDate), (CMYK; 908ppi;Up 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps (Up toDate), (Up AP- American Express-RegMark-4C.ai AP- AmericanExpress-RegMark-4C.ai (Up toDate), (Up sbs_fr_chg_plat_met- at americanexpress.com/exploreplatinum at PlatinumMembership Business of theworld Explore FineHotelsandResorts. hand-picked 975 atover head your andclear early Arrive TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

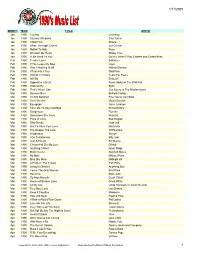

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

No More Mr. Nice Guy: Effects of Salient Motives on Women’S Mate

NO MORE MR. NICE GUY: EFFECTS OF SALIENT MOTIVES ON WOMEN’S MATE PREFERENCES by CHRISTOPER JAMES HOLLAND Bachelor of Arts, 2013 Knox College Galesburg, Illinois Masters of Science, 2016 Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the College of Science and Engineering Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research is the culmination of years of hard work and dedication on the part of many people. Many thanks to my advisor, Dr. Charles G. Lord, who’s continued feedback and advice was invaluable throughout the life of this research, from the start with ideas and hypotheses, to the end with paper drafts and editing. I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Charles Lord, Dr. Sarah Hill, Dr. Uma Tauber, Dr. Timothy Barth, and Dr. David Cross for their valuable input and support throughout the dissertation process. An especially deserving commendation goes out to Dr. Gary Bohem who agreed to sit on my committee on short notice to ensure my committee was adequately staffed for the defense. Lastly, thanks to my research assistants, Leslie Nolan, Tori Ludvigaria, Jacqui Faber, Ashley Mcfeeley, Serena V., Murphy Marx, Raylee Starnes, Nicholas Jones, and Elyssa Johnson for helping organize and run countless study sessions to collect the necessary data. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………….ii List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………..v List of Tables…………………………………………………….…………………………...…...v -

Sweet 16 Hot List

Sweet 16 Hot List Song Artist Happy Pharrell Best Day of My Life American Authors Run Run Run Talk Dirty to Me Jason Derulo Timber Pitbull Demons & Radioactive Imagine Dragons Dark Horse Katy Perry Find You Zedd Pumping Blood NoNoNo Animals Martin Garrix Empire State of Mind Jay Z The Monster Eminem Blurred Lines We found Love Rihanna/Calvin Love Me Again John Newman Dare You Hardwell Don't Say Goodnight Hot Chella Rae All Night Icona Pop Wild Heart The Vamps Tennis Court & Royals Lorde Songs by Coldplay Counting Stars One Republic Get Lucky Daft punk Sexy Back Justin Timberland Ain't it Fun Paramore City of Angels 30 Seconds Walking on a Dream Empire of the Sun If I loose Myself One Republic (w/Allesso mix) Every Teardrop is a Waterfall mix Coldplay & Swedish Mafia Hey Ho The Lumineers Turbulence Laidback Luke Steve Aoki Lil Jon Pursuit of Happiness Steve Aoki Heads will roll Yeah yeah yeah's A-trak remix Mercy Kanye West Crazy in love Beyonce and Jay-z Pop that Rick Ross, Lil Wayne, Drake Reason Nervo & Hook N Sling All night longer Sammy Adams Timber Ke$ha, Pitbull Alive Krewella Teach me how to dougie Cali Swag District Aye ladies Travis Porter #GETITRIGHT Miley Cyrus We can't stop Miley Cyrus Lip gloss Lil mama Turn down for what Laidback Luke Get low Lil Jon Shots LMFAO We found love Rihanna Hypnotize Biggie Smalls Scream and Shout Cupid Shuffle Wobble Hips Don’t Lie Sexy and I know it International Love Whistle Best Love Song Chris Brown Single Ladies Danza Kuduro Can’t Hold Us Kiss You One direction Don’t You worry Child Don’t -

77/Kid JIWW MOVING up WITHOUT MOVING ON...The Tour (Now in Progress), Their Experiencesin' Media Community on Ft

Late -Breaking News and Inflammati. Music Director. LORI has been the station's promo- sample of the Fall 1994 survey in Anchorage...yes tions assistant, and will continue hosting afternoon that's Alaska!According to a memo issued by BAUMGARTNER'S "BAD BOYS" SET FOR WORK! drive. Congratulations LORI! ARBITRON, it was determined that 6 diaries, which were returned from Anchorage County, were in Before he's even had the chance to try out the After a brief hiatus following her departure from fact returned from just two households.In addi- executive wash -room, newly appointed Sr. GIANT, MIA KLEIN joins the staff at PLATINUM tion, the memo goes on to state that these two V.P/PROMOTION for the WORK Group, Burt MUSIC. households "may have been influenced by media - Baumgartner is set to launch the label's inaugural related individuals." These "media related individ- project."BAD BOYS" (the soundtrack to the WHAT GOES AROUND COMES AROUND...Just a uals"it was discovered, are employed at upcoming COLUMBIA PICTURES film release of the few years ago, no station seemed safe from a for- KWHL/THE WHALE.Station G.M.. DENNIS same name) features a stellar line-up of today's mat switch to Country. Now it's Country stations BOOKEY admits that a former part-timer did agree hottest R&B and hip -hop artists, including WORK and programmers facing format flips.NewCity's (in violation of media affiliation rules) to accept Group's DIANA KING, WARREN G., 2PAC, INI Young Country KDIL/THE ARMADILLO, San four diaries when screened by ARBITRON. -

Hong Kong Martial Arts Films

GENDER, IDENTITY AND INFLUENCE: HONG KONG MARTIAL ARTS FILMS Gilbert Gerard Castillo, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2002 Approved: Donald E. Staples, Major Professor Harry Benshoff, Committee Member Harold Tanner, Committee Member Ben Levin, Graduate Coordinator of the Department of Radio, TV and Film Alan B. Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, TV and Film C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Castillo, Gilbert Gerard, Gender, Identity, and Influence: Hong Kong Martial Arts Films. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2002, 78 pp., references, 64 titles. This project is an examination of the Hong Kong film industry, focusing on the years leading up to the handover of Hong Kong to communist China. The influence of classical Chinese culture on gender representation in martial arts films is examined in order to formulate an understanding of how these films use gender issues to negotiate a sense of cultural identity in the face of unprecedented political change. In particular, the films of Hong Kong action stars Michelle Yeoh and Brigitte Lin are studied within a feminist and cultural studies framework for indications of identity formation through the highlighting of gender issues. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank the members of my committee all of whom gave me valuable suggestions and insights. I would also like to extend a special thank you to Dr. Staples who never failed to give me encouragement and always made me feel like a valuable member of our academic community.