Munich Security Report 2017 Post-Truth, Post-West, Post-Order?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers

January 2016 Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France, Daniele Fattibene Defence Budgets and Cooperation in Europe: Developments, Trends and Drivers Edited by Alessandro Marrone, Olivier De France and Daniele Fattibene Contributors: Bengt-Göran Bergstrand, FOI Marie-Louise Chagnaud, SWP Olivier De France, IRIS Thanos Dokos, ELIAMEP Daniele Fattibene, IAI Niklas Granholm, FOI John Louth, RUSI Alessandro Marrone, IAI Jean-Pierre Maulny, IRIS Francesca Monaco, IAI Paola Sartori, IAI Torben Schütz, SWP Marcin Terlikowski, PISM 1 Index Executive summary ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 List of abbreviations --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Chapter 1 - Defence spending in Europe in 2016 --------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.1 Bucking an old trend ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.2 Three scenarios ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 1.3 National data and analysis ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.1 Central and Eastern Europe -------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.3.2 Nordic region -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Coast Guard Connection

VOL 2, No . 4, WINTER 2019 A quarterly newsletter for retired senior leaders COAST GUARD from the U.S. Coast Guard providing a focused sampling of current events and service initiatives. The product can be repurposed for a wider CONNECTION audience as necessary. The product is collated and championed by CG-0923. Introduction Thank you for your continued interest in Coast Guard Connection. We appreciate and encourage the strong engagement of our retired senior leaders and fellow Coast Guard stakeholders. Your interest and advocacy are critical to our Service’s continued success. Earlier in February, we hosted a very successful Retired Senior Leadership Conference at Coast Guard Headquarters. Approximately 40 attendees—including the 21st and 24th Commandants—joined us for a day of discussion on the current state of your Coast Guard. The conversations were n Coast Guard CAPT Greg Fuller, Sector Humboldt Bay commander, lively and informative, with great dialogue between our current Rep. Jared Huffman (CA-2), CAPT James Pruett, 11th District chief of senior leader cohort and our retired senior leaders. We took staff, and Mayor Susan Seaman of Eureka, CA, (from left to right) pose the opportunity to recognize the leadership and impact of as they re-designate Eureka a Coast Guard City, Feb. 22, 2019 in Eureka. (U.S. Coast Guard) RADM Cari Thomas (USCG, Ret.) for her incredible work with Coast Guard Mutual Assistance (CGMA) during the 35-day On Friday, March 29, we join the rest of the nation in honoring government furlough. CGMA provided more than $8.4M in National Vietnam War Veterans Day. -

IS DEMOCRACY in TROUBLE? According to Many Scholars, Modern Liberal Democracy Has Advanced in Waves

IS DEMOCRACY IN TROUBLE? According to many scholars, modern liberal democracy has advanced in waves. But liberal democracy has also had its set- backs. Some argue that it is in trouble in the world today, and that the young millennial generation is losing faith in it. FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2017 Source: Freedom in the World 2017 This map was prepared by Freedom House, an independent organization that monitors and advocates for democratic government around the globe. According to this map, how free is your country? Which areas of the world appear to be the most free? Which appear to be the least free? (Freedom House) Since the American and French revolutions, there authoritarian leaders like Russia’s Vladimir Putin. have been three major waves of liberal democracies. Freedom House has rated countries “free,” “partly After each of the first two waves, authoritarian regimes free,” and “not free” for more than 70 years. Its Free- like those of Mussolini and Hitler arose. dom in the World report for 2016 identified 67 coun- A third wave of democracy began in the world in the tries with net declines in democratic rights and civil mid-1970s. It speeded up when the Soviet Union and the liberties. Only 36 countries had made gains. This nations it controlled in Eastern Europe collapsed. Liberal marked the 11th straight year that declines outnum- democracies were 25 percent of the world’s countries in bered gains in this category. 1975 but surged to 45 percent in 2000. The big news in the Freedom House report was that Many believed liberal democracy was on a perma- “free” countries (i.e., liberal democracies) dominated the nent upward trend. -

Symbolae Europaeae

SYMBOLAE EUROPAEAE POLITECHNIKA KOSZALIŃSKA SYMBOLAE EUROPAEAE STUDIA HUMANISTYCZNE POLITECHNIKI KOSZALIŃSKIEJ nr 8 Filozofia, historia, język i literatura, nauki o polityce KOSZALIN 2015 ISSN 1896-8945 Komitet Redakcyjny Bolesław Andrzejewski (przewodniczący) Zbigniew Danielewicz Małgorzata Sikora-Gaca (sekretarz) Redaktor statystyczny Urszula Kosowska Przewodniczący Uczelnianej Rady Wydawniczej Mirosław Maliński Projekt okładki Agnieszka Bil Skład, łamanie Karolina Ziobro © Copyright by Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Politechniki Koszalińskiej Koszalin 2015 WYDAWNICTWO UCZELNIANE POLITECHNIKI KOSZALIŃSKIEJ 75-620 Koszalin, ul. Racławicka 15-17 —————————————————————————————————— Koszalin 2015, wyd. I, ark. wyd. …, format B-5, nakład 100 egz. Druk Spis treści FILOZOFIA BOLESŁAW ANDRZEJEWSKI Komunikacyjne aspekty filozofii chrześcijańskiej w średniowieczu .................. 7 ZBIGNIEW DANIELEWICZ Leszka Kołakowskiego apologia Jezusa w kulturze Europy ............................ 19 MAGDALENA FILIPIAK Status konsensualnej koncepcji prawdy w komunikacyjnym projekcie filozofii Karla-Otto Apla ............................................................................................... 33 HISTORIA BOGUSŁAW POLAK Biskup Józef Gawlina wobec powstań śląskich i wielkopolskiego 1918-1921 ....................................................................................................... 45 MICHAŁ POLAK, KATARZYNA POLAK Działalność Polskiego Komitetu Ruchu Europejskiego na rzecz sprawy polskiej w latach 1964-1978 ........................................................................................ -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6"X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing theUMI World’s Information since 1938 300 North Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820321 Operational art and the German command system in World War I Meyer, Bradley John, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1088 by Meyer, Bradley John. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. ZeebRd. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 OPERATIONAL ART AND THE GERMAN COMMAND SYSTEM IN WORLD WAR I DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Bradley J. -

The Two Faces of Populism: Between Authoritarian and Democratic Populism

German Law Journal (2019), 20, pp. 390–400 doi:10.1017/glj.2019.20 ARTICLE The two faces of populism: Between authoritarian and democratic populism Bojan Bugaric* (Received 18 February 2019; accepted 20 February 2019) Abstract Populism is Janus-faced; simultaneously facing different directions. There is not a single form of populism, but rather a variety of different forms, each with profoundly different political consequences. Despite the current hegemony of authoritarian populism, a much different sort of populism is also possible: Democratic and anti-establishment populism, which combines elements of liberal and democratic convic- tions. Without understanding the political economy of the populist revolt, it is difficult to understand the true roots of populism, and consequently, to devise an appropriate democratic alternative to populism. Keywords: authoritarian populism; democratic populism; Karl Polanyi; political economy of populism A. Introduction There is a tendency in current constitutional thinking to reduce populism to a single set of universal elements. These theories juxtapose populism with constitutionalism and argue that pop- ulism is by definition antithetical to constitutionalism.1 Populism, according to this view, under- mines the very substance of constitutional (liberal) democracy. By attacking the core elements of constitutional democracy, such as independent courts, free media, civil rights and fair electoral rules, populism by necessity degenerates into one or another form of non-democratic and authori- tarian order. In this article, I argue that such an approach is not only historically inaccurate but also norma- tively flawed. There are historical examples of different forms of populism, like the New Deal in the US, which did not degenerate into authoritarianism and which actually helped the American democracy to survive the Big Depression of the 1930s. -

How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss

The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money by Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss A Special Report presented by The Interpreter, a project of the Institute of Modern Russia imrussia.org interpretermag.com The Institute of Modern Russia (IMR) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy organization—a think tank based in New York. IMR’s mission is to foster democratic and economic development in Russia through research, advocacy, public events, and grant-making. We are committed to strengthening respect for human rights, the rule of law, and civil society in Russia. Our goal is to promote a principles- based approach to US-Russia relations and Russia’s integration into the community of democracies. The Interpreter is a daily online journal dedicated primarily to translating media from the Russian press and blogosphere into English and reporting on events inside Russia and in countries directly impacted by Russia’s foreign policy. Conceived as a kind of “Inopressa in reverse,” The Interpreter aspires to dismantle the language barrier that separates journalists, Russia analysts, policymakers, diplomats and interested laymen in the English-speaking world from the debates, scandals, intrigues and political developments taking place in the Russian Federation. CONTENTS Introductions ...................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................... 6 Background ........................................................................ -

Technological Revolution, Democratic Recession and Climate Change: the Limits of Law in a Changing World

TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION, DEMOCRATIC RECESSION AND CLIMATE CHANGE: THE LIMITS OF LAW IN A CHANGING WORLD Luís Roberto Barroso Senior Fellow, Carr Center for Human Rights Policy Justice, Brazilian Supreme Court CARR CENTER DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Discussion Paper 2019-009 For Academic Citation: Luís Roberto Barroso. Technological Revolution, Democratic Recession and Climate Change: The Limits of Law in a Changing World. CCDP 2019-009. September 2019. The views expressed in Carr Center Discussion Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Harvard Kennedy School or of Harvard University. Discussion Papers have not undergone formal review and approval. Such papers are included in this series to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Technological Revolution, Democratic Recession and Climate Change: The Limits of Law in a Changing World About the Author Luís Roberto Barroso is a Senior Fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. He is a Justice at the Brazilian Supreme Court and a Law Professor at Rio de Janeiro State University. He holds a Master’s degree in Law from Yale Law School (LLM), and a Doctor’s degree (SJD) from the Rio de Janeiro State University. He was a Visiting Scholar at Harvard Law School in 2011 and has been Visiting Professor at different universities in Brazil and other countries. Carr Center for Human Rights Policy Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.carrcenter.hks.harvard.edu Copyright 2019 Discussion Paper September 2019 Table of Contents TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION, DEMOCRATIC RECESSION AND CLIMATE CHANGE: THE LIMITS OF LAW IN A CHANGING WORLD ..................................................................................................................................... -

Military Tribunal, Indictments

MILITARY TRIBUNALS Case No. 12 THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA -against- WILHELM' VON LEEB, HUGO SPERRLE, GEORG KARL FRIEDRICH-WILHELM VON KUECHLER, JOHANNES BLASKOWITZ, HERMANN HOTH, HANS REINHARDT. HANS VON SALMUTH, KARL HOL LIDT, .OTTO SCHNmWIND,. KARL VON ROQUES, HERMANN REINECKE., WALTERWARLIMONT, OTTO WOEHLER;. and RUDOLF LEHMANN. Defendants OFFICE OF MILITARY GOVERNMENT FOR GERMANY (US) NORNBERG 1947 • PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ TABLE OF CONTENTS - Page INTRODUCTORY 1 COUNT ONE-CRIMES AGAINST PEACE 6 A Austria 'and Czechoslovakia 7 B. Poland, France and The United Kingdom 9 C. Denmark and Norway 10 D. Belgium, The Netherland.; and Luxembourg 11 E. Yugoslavia and Greece 14 F. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics 17 G. The United states of America 20 . , COUNT TWO-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST ENEMY BELLIGERENTS AND PRISONERS OF WAR 21 A: The "Commissar" Order , 22 B. The "Commando" Order . 23 C, Prohibited Labor of Prisoners of Wal 24 D. Murder and III Treatment of Prisoners of War 25 . COUNT THREE-WAR CRIMES AND CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: CRIMES AGAINST CIVILIANS 27 A Deportation and Enslavement of Civilians . 29 B. Plunder of Public and Private Property, Wanton Destruc tion, and Devastation not Justified by Military Necessity. 31 C. Murder, III Treatment and Persecution 'of Civilian Popu- lations . 32 COUNT FOUR-COMMON PLAN OR CONSPIRACY 39 APPENDIX A-STATEMENT OF MILITARY POSITIONS HELD BY THE DEFENDANTS AND CO-PARTICIPANTS 40 2 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/c6a171/ INDICTMENT -

The Bridge Between Contemporary and Future Strategic Thinking for the Global Military Helicopter Community

presents the 16th annual: Main Conference: 31 January-1 February 2017 Post-Conference Focus Day: 2 February 2017 London, UK THE BRIDGE BETWEEN CONTEMPORARY AND FUTURE STRATEGIC THINKING FOR THE GLOBAL MILITARY HELICOPTER COMMUNITY THE 2017 INTERNATIONAL SPEAKER PANEL INCLUDES: Major General Richard Felton Major General Leon N Thurgood Major General Andreas Marlow Commander Deputy for Acquisition and Systems Commander, Rapid Forces Division Joint Helicopter Command Management, U.S. Office of the Assistant German Army Secretary of the Army (Acquisition, Logistics and Technology) Major General Khalil Dar Lieutenant General Baldev Raj Mahat Major General Antonio Bettelli General Officer Commanding Chief of the General Staff Commander Pakistan Army Aviation Command Nepalese Army Italian Army Aviation Sponsored By: Dear Colleague, 2017 SPEAKERS: Lieutenant General Baldev Raj Mahat Chief of the General Staff, Nepalese Army I am delighted to invite you to the upcoming International Major General Richard Felton Military Helicopter conference, to be held in London from 31st Commander, Joint Helicopter Command nd January-2 February 2017. Now in its 16th year, the conference Major General Leon N Thurgood will gather practitioners, providers and subject-matter experts Deputy for Acquisition and Systems Management Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army from across the rotary and broader defence communities to (Acquisition, Logistics and Technology) take an in-depth, critical view of the current and future role and Major General Khalil Dar capabilities of military helicopters. General Officer Commanding, Army Aviation Command Since our last meeting in January, Heads of State and Major General Andreas Marlow Commander, Government of the member countries of NATO met in Warsaw Rapid Forces Division, German Army to set out common strategic objectives and measure existing Major General Antonio Bettelli Commander, Italian Army Aviation and emerging threats for the years ahead. -

MAY 2015 Marianne Giambrone, Editor Volume 26 Issue 5

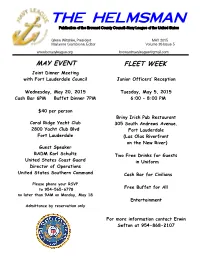

THE HELMSMAN Publication of the Broward County Council—Navy League of the United States Glenn Wiltshire, President MAY 2015 Marianne Giambrone, Editor Volume 26 Issue 5 www.bcnavyleague.org [email protected] MAY EVENT FLEET WEEK Joint Dinner Meeting with Fort Lauderdale Council Junior Officers’ Reception Wednesday, May 20, 2015 Tuesday, May 5, 2015 Cash Bar 6PM Buffet Dinner 7PM 6:00 – 8:00 PM $40 per person Briny Irish Pub Restaurant Coral Ridge Yacht Club 305 South Andrews Avenue. 2800 Yacht Club Blvd Fort Lauderdale Fort Lauderdale (Las Olas Riverfront on the New River) Guest Speaker RADM Karl Schultz Two Free Drinks for Guests United States Coast Guard in Uniform Director of Operations United States Southern Command Cash Bar for Civilians Please phone your RSVP to 954-565-6778 Free Buffet for All no later than 9AM on Monday, May 18 Entertainment Admittance by reservation only For more information contact Erwin Sefton at 954-868-2107 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Fleet Week 2015 is almost here, with the open- of the unit. Some of us will be back there on ing welcoming event at the Hard Rock Hotel and May 1st to attend the Seventh Coast Guard Dis- Casino on May 4, 2015. Volunteers are still need- trict Change of Command Ceremony and Retire- ed to assist with tours, special events, etc., so go ment Ceremony for RADM Jake Korn, who has online to register as a volunteer at been a strong supporter of the Navy League dur- www.browardnavydaysinc.org. Shelley Beck is co- ing his two years as District Commander. -

Peter Pomerantsev. This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality

Peter Pomerantsev. This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality. New York: Public Affairs, 2019. Reviewed by: Mariia Shuvalova Source: Kyiv-Mohyla Humanities Journal 7 (2020): 263–265 Published by: National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy http://kmhj.ukma.edu.ua/ Peter Pomerantsev This In Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality New York: Public Affairs, 2019. 236 pp. ISBN 978-1-5417-6211-4 Reviewed by Mariia Shuvalova This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality, beginning with a scene on an Odesa beach and ending with rethinking the history of Chernivtsi, received much attention when published. The book was reviewed in The Guardian, The New York Times, The Economist, The Financial Times, The Irish Times, The Telegraph, Foreign Affairs, The London School of Economics Book Review, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. In the period of a year the book was translated into Ukrainian, Estonian, and Spanish. A trigger for public attention is the book’s topic. The author investigates information campaigns aiming to reduce, suppress, or crash democratic processes in the contemporary world. Although this topic has been broadly discussed, the book is distinguished by an insider’s perspective, its style, and its intention to grasp the large-scale phenomena behind the information wars. Propaganda and censorship are intertwined with the author’s personal and professional life. Kyiv- born Peter Pomerantsev currently lives in London. His family, repeatedly persecuted by the Soviet government, moved to Germany in the late 1970s, then to the UK. Pomerantsev worked in the media sphere for almost 20 years, including a decade of producing TV shows and broadcast programs in Moscow.