The Evolution of the American Brewing Industry Alfred G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grub Split Greens

GREENS GRILLED CHICKEN AND BEETS SALAD - $10.95 Zero in on this uniquely-served Apple, Baby Spinach, Crumbled Goat Cheese and Pecan Salad with Strawberry Vinaigrette CLASSIC CAESAR SALAD - $10.95 Crisp Romaine Heart, Garlic Croutons, Shaved Parmigiano Reggiano, Creamy Caesar Dressing ORZO PASTA SALAD - $11.95 Turkey, Spinach, Basil, Cremini Mushrooms, Sun Dried Tomato, Chick Peas, Herbed Vinaigrette SUNSHINE SALAD - $11.95 Kale, Spinach, Red Pepper, Cucumber, Cherry Tomato, Green Beans, Carrots, Radish, Blueberry, Sunflower Seeds, Citrus Vinaigrette SPLIT PRETZEL STICK - $10.95 Fresh Baked Pretzel Served with Beer Cheese 7|10 LAYERS DIP - $12.95 Pick up this Seven-Layer Split! Refried Beans, Guacamole, Sour Cream, Salsa, Shredded Cheddar Cheese, Tomato, Black Olives and Green Onions layered up fresh and served with Tortilla Chips. SMOKED CHICKEN WINGS - $13.95 Buffalo Sauce, BBQ-Ranch, Sriracha Ketchup, Celery stick SIDEWINDER GARLIC & PARMESAN FRIES - $6.95 Wind your way into this delicious dish! Crispy French Fry Curls seasoned with our signature Garlic and Parmesan blend GRUB TATER TOTS WAFFLE SANDWICH - $14.95 No boring bread here. We smash Tater Tots on a waffle iron and sandwich in Italian-imported Rosemary Ham and Swiss Cheese then smother the whole thing in Beer Cheese. ALABAMA SMOKE - $11.95 Just as good as a turkey on the lanes! Dig into Smoked Turkey, Alabama White BBQ Sauce, Balsamic Onion Jam, Pickles, Bacon, Cheddar Cheese, Lettuce and Tomato on a Ciabatta Bun. Served with a side of Coleslaw. “THE BELLY STACK” - $14.95 Get this stack in your belly! Piles of Smoked Pulled Pork and Prime Brisket of Beef with Chipotle Aioli and Baby Spinach, served on a Ciabatta Roll. -

Vermont Beer : History of a Brewing Revolution Pdf, Epub, Ebook

VERMONT BEER : HISTORY OF A BREWING REVOLUTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kurt Staudter | 210 pages | 01 Jul 2014 | History Press Library Editions | 9781540210197 | English | none Vermont Beer : History of a Brewing Revolution PDF Book Seven Days needs your financial support! When Carri Uranga interviewed for a job at Magic Hat in , she sat across a table from Johnson and longtime general manager Steve Hood she thinks; memories made at breweries tend to be fuzzy, especially two decades later. Many of Magic Hat's offbeat offerings were home runs, though — so many, in fact, that by it was the eighth-largest craft brewery in the country. A hop shortage reportedly due to a fire in Washington state and bad storms in Germany leads to brewers to band together to solve a problem in the supply chain. Charleston: A Historic Walking Tour. Showing The event will include demos, meetings about the project, a book talk by Kurt Staudter, author of "Vermont Beer: History of a Brewing Revolution," and a 5 p. Richards, 34, with minimal brewing experience under his belt, became intrigued by ginger beer after reading about its historical connections to the spice-trade shipping days of yore. National sales figures confirm that craft customers, many of whom were weaned on 9, are moving away from regional breweries like Magic Hat and toward microbreweries — defined as breweries that produce fewer than 15, barrels per year. When the Pilgrims sailed for America, they hoped to find a place to settle where the farmland would be rich and the climate congenial. American Palate , Beer! Craft brewing is kind of like that. -

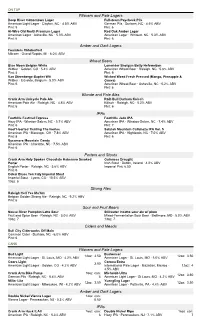

Parkside Raleigh Menubuilder Print

ON TAP Pilsners and Pale Lagers Deep River Cottontown Lager Fullsteam Paycheck Pils American Light Lager · Clayton, NC · 4.5% ABV German Pils · Durham, NC · 4.5% ABV Pint: 5 Pint: 6 Hi-Wire Old North Premium Lager Red Oak Amber Lager American Lager · Asheville, NC · 5.0% ABV American Lager · Whitsett, NC · 5.3% ABV Pint: 6 Pint: 6 Amber and Dark Lagers Founders Oktoberfest Märzen · Grand Rapids, MI · 6.0% ABV Wheat Beers Blue Moon Belgian White Lonerider Shotgun Betty Hefeweizen Witbier · Golden, CO · 5.4% ABV American Wheat Beer · Raleigh, NC · 5.8% ABV Pint: 5 Pint: 6 Van Steenberge Baptist Wit Wicked Weed Fresh Pressed (Mango, Pineapple & Witbier · Ertvelde, Belgium · 5.0% ABV Guava) Pint: 6 American Wheat Beer · Asheville, NC · 5.2% ABV Pint: 6 Blonde and Pale Ales Crank Arm Unicycle Pale Ale R&D Bull Durham Kolsch American Pale Ale · Raleigh, NC · 4.8% ABV Kölsch · Raleigh, NC · 5.2% ABV Pint: 6 Pint: 6 IPAs Foothills Festival Express Foothills Jade IPA Hazy IPA · Winston-Salem, NC · 5.7% ABV American IPA · Winston-Salem, NC · 7.4% ABV Pint: 6 Pint: 7 Hoof Hearted Tickling The Ivories Satulah Mountain Cullahaza IPA Vol. 5 American IPA · Marengo , OH · 7.8% ABV American IPA · Highlands, NC · 7.0% ABV Pint: 8 Pint: 6 Sycamore Mountain Candy American IPA · Charlotte, NC · 7.5% ABV Pint: 6 Porters and Stouts Crank Arm Holy Spokes Chocolate Habenaro Smoked Guinness Draught Porter Irish Stout · Dublin, Ireland · 4.2% ABV English Porter · Raleigh, NC · 5.6% ABV Imperial Pint: 6.50 Pint: 6 Oskar Blues Ten Fidy Imperial Stout Imperial Stout · Lyons, CO · 10.5% ABV 10oz: 5 Strong Ales Raleigh Hell Yes Ma'Am Belgian Golden Strong Ale · Raleigh, NC · 9.2% ABV Pint: 6 Sour and Fruit Beers Neuse River Pumpkin Latte Sour Stillwater Insetto sour ale w/ plum Fruit and Spice Beer · Raleigh, NC · 5.0% ABV Mixed-Fermentation Sour Beer · Baltimore, MD · 5.0% ABV 13oz: 7 13oz: 7 Ciders and Meads Bull City Ciderworks Off Main Common Cider · Durham, NC · 6.0% ABV Pint: 6 CANS Pilsners and Pale Lagers Bud Light Budweiser 12oz: 3.50 12oz: 3.50 American Light Lager · St. -

An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: the Response Based Approach

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2000 An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach Cheryl Elaine Brookshear University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine, "An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach" (2000). Theses (Historic Preservation). 364. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine (2000). An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Brookshear, Cheryl Elaine (2000). An Interpretation of the Captain Frederick Pabst Mansion: The Response Based Approach. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/364 ^mm^'^^'^ M ilj- hmi mmtmm mini mm\ m m mm UNIVERSITVy PENNSYLV\NL\ LIBRARIES AN INTERPRETATION OF THE CAPTAIN FREDERICK PABST MANSION: THE RESPONSE BASED APPROACH Cheryl Elaine Brookshear A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Facuhies of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE 2000 V^u^^ Reader MossyPh. -

The Deity's Beer List.Xls

Page 1 The Deity's Beer List.xls 1 #9 Not Quite Pale Ale Magic Hat Brewing Co Burlington, VT 2 1837 Unibroue Chambly,QC 7% 3 10th Anniversary Ale Granville Island Brewing Co. Vancouver,BC 5.5% 4 1664 de Kronenbourg Kronenbourg Brasseries Stasbourg,France 6% 5 16th Avenue Pilsner Big River Grille & Brewing Works Nashville, TN 6 1889 Lager Walkerville Brewing Co Windsor 5% 7 1892 Traditional Ale Quidi Vidi Brewing St. John,NF 5% 8 3 Monts St.Syvestre Cappel,France 8% 9 3 Peat Wheat Beer Hops Brewery Scottsdale, AZ 10 32 Inning Ale Uno Pizzeria Chicago 11 3C Extreme Double IPA Nodding Head Brewery Philadelphia, Pa. 12 46'er IPA Lake Placid Pub & Brewery Plattsburg , NY 13 55 Lager Beer Northern Breweries Ltd Sault Ste.Marie,ON 5% 14 60 Minute IPA Dogfishhead Brewing Lewes, DE 15 700 Level Beer Nodding Head Brewery Philadelphia, Pa. 16 8.6 Speciaal Bier BierBrouwerij Lieshout Statiegeld, Holland 8.6% 17 80 Shilling Ale Caledonian Brewing Edinburgh, Scotland 18 90 Minute IPA Dogfishhead Brewing Lewes, DE 19 Abbaye de Bonne-Esperance Brasserie Lefebvre SA Quenast,Belgium 8.3% 20 Abbaye de Leffe S.A. Interbrew Brussels, Belgium 6.5% 21 Abbaye de Leffe Blonde S.A. Interbrew Brussels, Belgium 6.6% 22 AbBIBCbKE Lvivske Premium Lager Lvivska Brewery, Ukraine 5.2% 23 Acadian Pilsener Acadian Brewing Co. LLC New Orleans, LA 24 Acme Brown Ale North Coast Brewing Co. Fort Bragg, CA 25 Actien~Alt-Dortmunder Actien Brauerei Dortmund,Germany 5.6% 26 Adnam's Bitter Sole Bay Brewery Southwold UK 27 Adnams Suffolk Strong Bitter (SSB) Sole Bay Brewery Southwold UK 28 Aecht Ochlenferla Rauchbier Brauerei Heller Bamberg Bamberg, Germany 4.5% 29 Aegean Hellas Beer Atalanti Brewery Atalanti,Greece 4.8% 30 Affligem Dobbel Abbey Ale N.V. -

2018 Annual Report

AB InBev annual report 2018 AB InBev - 2018 Annual Report 2018 Annual Report Shaping the future. 3 Bringing People Together for a Better World. We are building a company to last, brewing beer and building brands that will continue to bring people together for the next 100 years and beyond. Who is AB InBev? We have a passion for beer. We are constantly Dreaming big is in our DNA innovating for our Brewing the world’s most loved consumers beers, building iconic brands and Our consumer is the boss. As a creating meaningful experiences consumer-centric company, we are what energize and are relentlessly committed to inspire us. We empower innovation and exploring new our people to push the products and opportunities to boundaries of what is excite our consumers around possible. Through hard the world. work and the strength of our teams, we can achieve anything for our consumers, our people and our communities. Beer is the original social network With centuries of brewing history, we have seen countless new friendships, connections and experiences built on a shared love of beer. We connect with consumers through culturally relevant movements and the passion points of music, sports and entertainment. 8/10 Our portfolio now offers more 8 out of the 10 most than 500 brands and eight of the top 10 most valuable beer brands valuable beer brands worldwide, according to BrandZ™. worldwide according to BrandZTM. We want every experience with beer to be a positive one We work with communities, experts and industry peers to contribute to reducing the harmful use of alcohol and help ensure that consumers are empowered to make smart choices. -

A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 7-3-2018 A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 Lyndsay Danielle Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Lyndsay Danielle, "A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4497. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6381 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: The Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 by Lyndsay Danielle Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Catherine McNeur, Chair Katrine Barber Joseph Bohling Nathan McClintock Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Lyndsay Danielle Smith i Abstract For decades prior to National Prohibition, the “liquor question” received attention from various temperance, prohibition, and liquor interest groups. Between 1880 and 1920, these groups gained public interest in their own way. The liquor interests defended their industries against politicians, religious leaders, and social reformers, but ultimately failed. While current historical scholarship links the different liquor industries together, the beer industry constantly worked to distinguish itself from other alcoholic beverages. -

Big Beer Duopoly a Primer for Policymakers and Regulators

Big Beer Duopoly A Primer for Policymakers and Regulators Marin Institute Report October 2009 Marin Institute Big Beer Duopoly A Primer for Policymakers and Regulators Executive Summary While the U.S. beer industry has been consolidating at a rapid pace for years, 2008 saw the most dramatic changes in industry history to date. With the creation of two new global corporate entities, Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI) and MillerCoors, how beer is marketed and sold in this country will never be the same. Anheuser-Busch InBev is based in Belgium and largely supported and managed by Brazilian leadership, while MillerCoors is majority-controlled by SABMiller out of London. It is critical for federal and state policymakers, as well as alcohol regulators and control advocates to understand these changes and anticipate forthcoming challenges from this new duopoly. This report describes the two industry players who now control 80 percent of the U.S. beer market, and offers responses to new policy challenges that are likely to negatively impact public health and safety. The new beer duopoly brings tremendous power to ABI and MillerCoors: power that impacts Congress, the Office of the President, federal agencies, and state lawmakers and regulators. Summary of Findings • Beer industry consolidation has resulted in the concentration of corporate power and beer market control in the hands of two beer giants, Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI) and MillerCoors LLC. • The American beer industry is no longer American. Eighty percent of the U.S. beer industry is controlled by one corporation based in Belgium, and another based in England. • The mergers of ABI and MillerCoors occurred within months of each other, and both were approved much quicker than the usual merger process. -

Sheriff's Reports- Jefferson County SHERIFF's OFFICE JEFFERSON COUNTY GOLDEN, COLORAOO

Sheriff's Reports- Jefferson County SHERIFF'S OFFICE JEFFERSON COUNTY GOLDEN, COLORAOO REFERENCE: ADOLPH COORS, III, VICTD-1 X:!DNAPING DATE: FEBRUARY 9, 1960 FRCltt: 7£ . LEWIS HA\JLEY, UNDERSHERIFF I &rri ved at the scene South of Morrison t-1here Coors' car v1as being tov1ed &\·ray at approximately 4&00 P.M., this date. Upon arrh·inq at the scene, Lt. !Cechter and Captain Bray informed me of what the situation was. I looked at the ecene and saw '"here the blood spote were removed on the \!!est side of the hrid;re ;..rhere tho dirt samplos were taken and placed in a baq by Lab man, Dale Ryder. I also was sho-vm the hat and the cap and glasses that were found on the East side of the bridge. I then proceeded H-i th the Sheriff and Captain Bray to the Adolph Coors, III residence rlhereao Captain Bray and I interviel'sed Mrs. Coors in relation t o the timo that Ad Coors dep&r ted from the house that AM; wherein she replied to us he left t he house approxili!Iltely five minutes to eiqht, FebruarY 9, 1960. 11heroas Hrs. Mary Coors qave Captain Harold Bray and myself the tYPO of clothing that she remembered that Ad Coors \~as wearing on this morning; #1 - & kahki type baaeb&ll cap, a navy blue, quilted nylon, parka type coat, blue flannel pants and a pair of hiqh top shoes. We also asked if there \-Jere any guns missinq from the house. ~fuile at the house I ordered a tape recorder put on the telephone and traoo all incominq calls. -

Anheuser-Busch Inbev

Our Dream: Anheuser-Busch InBev Annual Report 2014 1 ABOUT ANHEUSER-BUSCH INBEV Best Beer Company Bringing People Together For a Better World Contents 1 Our Manifesto 2 Letter to Shareholders 6 Strong Strategic Foundation 20 Growth Driven Platforms 36 Dream-People-Culture 42 Bringing People Together For a Better World 49 Financial Report 155 Corporate Governance Statement Open the foldout for an overview of our financial performance. A nheuser-Busch InBev Annual / 2014 Report Anheuser-Busch InBev 2014 Annual Report ab-inbev.com Our Dream: Anheuser-Busch InBev Annual Report 2014 1 ABOUT ANHEUSER-BUSCH INBEV Best Beer Company Bringing People Together For a Better World Contents 1 Our Manifesto 2 Letter to Shareholders 6 Strong Strategic Foundation 20 Growth Driven Platforms 36 Dream-People-Culture 42 Bringing People Together For a Better World 49 Financial Report 155 Corporate Governance Statement Open the foldout for an overview of our financial performance. A nheuser-Busch InBev Annual / 2014 Report Anheuser-Busch InBev 2014 Annual Report ab-inbev.com Anheuser-Busch InBev Annual Report 2014 1 ABOUT ANHEUSER-BUSCH INBEV About Revenue was Focus Brand volume EBITDA grew 6.6% Normalized profit Net debt to EBITDA 47 063 million USD, increased 2.2% and to 18 542 million USD, attributable to equity was 2.27 times. Anheuser-Busch InBev an organic increase accounted for 68% of and EBITDA margin holders rose 11.7% Driving Change For of 5.9%, and our own beer volume. was up 25 basis points in nominal terms to Anheuser-Busch InBev (Euronext: ABI, NYSE: BUD) is the leading AB InBev’s dedication to heritage and quality originates from revenue/hl rose 5.3%. -

2016 Sustainability Report MULTI BINTANG INDONESIA

2016 Sustainability Report MULTI BINTANG INDONESIA 1 2 2016 Sustainability Report MULTI BINTANG INDONESIA 2016 Sustainability Report MULTI BINTANG INDONESIA 3 DAFTAR ISI Content Ikhtisar Profil perusahaan Laporan manajemen highlights company management profile report 06 Informasi bagi Pemegang 13 Visi dan Misi Kami 32 Surat dari Dewan Saham Our Vision and Mission Komisaris Information For Letter from the Board of 20 Sejarah Perusahaan Shareholders Commissioners Company Milestones 07 Kronologi Pencatatan 40 Profil Dewan Komisaris 22 Struktur Organisasi Saham Profil Board of Organization Structure Chronology of Share Commissioners Listing 25 Penghargaan 2016 48 Laporan Direksi Award Received in 2016 10 Ikhtisar Data Keuangan Report of the Board of Summary of Financial 28 Peristiwa Penting 2016 Directors Data 2016 Event Highlights 58 Profil Direksi Profile of the Board of Directors 4 2016 Sustainability Report MULTI BINTANG INDONESIA Analisa dan pembahasan manajemen Tata kelola perusahaan Laporan keuangan management's corporate financial discussion and governance statements analysis 65 Tinjauan Industri 110 Struktur Tata Kelola 140 Surat Pernyataan Anggota Industry Review GCG Structures Dewan Komisaris dan Direksi tentang Tanggung 66 Tinjauan Usaha 131 Sekretaris Perusahaan Jawab atas Laporan Tahunan Operational Review Corporate Secretary 2016 90 Tinjauan Keuangan 135 Manajemen Risiko Board of Directors and Board Financial Review Risk Management of Commissioners‘ Statement 98 Tanggung Jawab Sosial regarding the Responsibility Perusahaan -

A TIMELINE for GOLDEN, COLORADO (Revised October 2003)

A TIMELINE FOR GOLDEN, COLORADO (Revised October 2003) "When a society or a civilization perishes, one condition can always be found. They forgot where they came from." Carl Sandburg This time-line was originally created by the Golden Historic Preservation Board for the 1995 Golden community meetings concerning growth. It is intended to illustrate some of the events and thoughts that helped shape Golden. Major historical events and common day-to-day happenings that influenced the lives of the people of Golden are included. Corrections, additions, and suggestions are welcome and may be relayed to either the Historic Preservation Board or the Planning Department at 384-8097. The information concerning events in Golden was gathered from a variety of sources. Among those used were: • The Colorado Transcript • The Golden Transcript • The Rocky Mountain News • The Denver Post State of Colorado Web pages, in particular the Colorado State Archives The League of Women Voters annual reports Golden, The 19th Century: A Colorado Chronicle. Lorraine Wagenbach and Jo Ann Thistlewood. Harbinger House, Littleton, 1987 The Shining Mountains. Georgina Brown. B & B Printers, Gunnison. 1976 The 1989 Survey of Historic Buildings in Downtown Golden. R. Laurie Simmons and Christine Whitacre, Front Range Research Associates, Inc. Report on file at the City of Golden Planning and Development Department. Survey of Golden Historic Buildings. by R. Laurie Simmons and Christine Whitacre, Front Range Research Associates, Inc. Report on file at the City of Golden Planning and Development Department. Golden Survey of Historic Buildings, 1991. R. Laurie Simmons and Thomas H. Simmons. Front Range Research Associates, Inc.