Sappho: ]Fragments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sappho of Lesbos [Born C

Sappho of Lesbos [born c. 612 B.C.] Know the following people, places, and terms: Aphrodite (=Kypris [refers to her sanctuary on Cyprus], =Cytherea [refers to her sanctuary on Cythera]) Eros, Aphrodite's son (sometimes known as Boy, Love or Cupid) Helen, wife of Menelaus, abducted by Paris to Troy Artemis, sister of Phoebus Apollo, goddess of the hunt Hector, greatest of the Trojan warriors, son of King Priam Andromache, Hector's wife Sardis, a town in Lydia, the area of Asia Minor across from Lesbos choriamb: − ∪ ∪ − Sapphic meter: three hendecasyllabic lines − ∪ − x | − ∪ ∪ − | ∪ − − followed by an Adonean − ∪ ∪ − | − 1. What is Sappho's world like? With whom does she associate and care for? What recurring images do we find in Sappho's poetry? In short, what did she value? 2. How is Aphrodite portrayed? Playful? Serious? Powerful? What were her powers? attributes? How does Sappho's view of Aphrodite compare with Homer's and Hesiod's? Whose view do you prefer? 3. What is Sappho's attitude toward love? Does Sappho's portrayal of Aphrodite (her theory of love, if you will) correspond to her actual relationships (i.e. the practice of love)? 4. What kind of relationship did Sappho have with her hetairai , "female companions"? Was it physical as well as emotional? Was there an intellectual component? If you were to speculate, what were the reasons for Sappho's attachment to her companions? What evidence is there that Sappho's hetairai were attracted to her? Is there any evidence in her poems of the erastes-eromenos relationship that we see in classical Athens? 5. -

Lawyers in Willa Cather's Fiction, Nebraska Lawyer

Lawyers in Willa Cather’s Fiction: The Good, The Bad and The Really Ugly by Laurie Smith Camp Cather Homestead near Red Cloud NE uch of the world knows Nebraska through the literature of If Nebraska’s preeminent lawyer and legal scholar fared so poorly in Willa Cather.1 Because her characters were often based on Cather’s estimation, what did she think of other members of the bar? Mthe Nebraskans she encountered in her early years,2 her books and stories invite us to see ourselves as others see us— The Good: whether we like it or not. In “A Lost Lady,”4 Judge Pommeroy was a modest and conscientious Roscoe Pound didn’t like it one bit when Cather excoriated him as a lawyer in the mythical town of Sweetwater, Nebraska. Pommeroy pompous bully in an 1894 ”character study” published by the advised his client, Captain Daniel Forrester,5 during Forrester’s University of Nebraska. She said: “He loves to take rather weak- prosperous years, and helped him to meet all his legal and moral minded persons and browbeat them, argue them down, Latin them obligations when the depression of the 1890's closed banks and col- into a corner, and botany them into a shapeless mass.”3 lapsed investments. Pommeroy appealed to the integrity of his clients, guided them by example, and encouraged them to respect Laurie Smith Camp has served as the rights of others. He agonized about the decline of ethical stan- Nebraska’s deputy attorney general dards in the Nebraska legal profession, and advised his own nephew for criminal matters since 1995. -

Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic

SOFIA COPPOLA AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AN APPEALING AESTHETIC by LEILA OZERAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of Cinema Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Leila Ozeran for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cinema Studies to be taken June 2016 Title: Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic Approved: r--~ ~ Professor Priscilla Pena Ovalle This thesis grew out of an interest in the films of female directors, producers, and writers and the substantially lower opportunities for such filmmakers in Hollywood and Independent film. The particular look and atmosphere which Sofia Coppola is able to compose in her five films is a point of interest and a viable course of study. This project uses her fifth and latest film, Bling Ring (2013), to showcase Coppola's merits as a filmmaker at the intersection of box office and critical appeal. I first describe the current filmmaking landscape in terms of gender. Using studies by Dr. Martha Lauzen from San Diego State University and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media to illustrate the statistical lack of a female presence in creative film roles and also why it is important to have women represented in above-the-line positions. Then I used close readings of Bling Ring to analyze formal aspects of Sofia Coppola's filmmaking style namely her use of distinct color palettes, provocative soundtracks, car shots, and tableaus. Third and lastly I went on to describe the sociocultural aspects of Coppola's interpretation of the "Sling Ring." The way the film explores the relationships between characters, portrays parents as absent or misguided, and through film form shows the pervasiveness of celebrity culture, Sofia Coppola has given Bling Ring has a central ii message, substance, and meaning: glamorous contemporary celebrity culture can have dangerous consequences on unchecked youth. -

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

The Role of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr. 1 Keith Stanley

The Rôle of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr.1 Stanley, Keith Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Winter 1976; 17, 4; ProQuest pg. 305 The Role of Aphrodite in Sappho Fr. 1 Keith Stanley APPHO'S Hymn to Aphrodite, standing so near to the beginning of Sour evidence for the religious and poetic traditions it embodies, remains a locus of disagreement about the function of the goddess in the poem and the degree of seriousness intended by Sappho's plea for her help. Wilamowitz thought sparrows' wings unsuited to the task of drawing Aphrodite's chariot, and proposed that Sappho's report of her epiphany described a vision experienced ovap, not v7rap.l Archibald Cameron ventured further, suggesting that the description of Aphrodite's flight was couched not in the language of "the real religious tradition of epiphany and its effect on mortals" but was "Homeric and conventional"; and that the vision was not, therefore, the record of a genuine religious experience, but derived rather from "the bright world of Homer's fancy."2 Thus he judged the tone of the ode to be one of seriousness tempered by "a vein of prettiness and almost of playfulness" and concluded that there was no special ur gency in Sappho's petition itself. While more recent opinion has tended to regard the episode as a poetic fiction which serves to 'mythologize' a genuine emotion, Sir Denys Page has not only maintained that Aphrodite's descent is a "flight of fancy, with much detail irrelevant to her present theme," but argued further that the poem as a whole is a lightly ironic melange of passion and self-mockery.3 Despite a con- 1 Sappho und Simonides (Berlin 1913) 45, with Der Glaube der Hellenen 3 II (Basel 1959) 109; so also J. -

Select Epigrams from the Greek Anthology

SELECT EPIGRAMS FROM THE GREEK ANTHOLOGY J. W. MACKAIL∗ Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. PREPARER’S NOTE This book was published in 1890 by Longmans, Green, and Co., London; and New York: 15 East 16th Street. The epigrams in the book are given both in Greek and in English. This text includes only the English. Where Greek is present in short citations, it has been given here in transliterated form and marked with brackets. A chapter of Notes on the translations has also been omitted. eti pou proima leuxoia Meleager in /Anth. Pal./ iv. 1. Dim now and soil’d, Like the soil’d tissue of white violets Left, freshly gather’d, on their native bank. M. Arnold, /Sohrab and Rustum/. PREFACE The purpose of this book is to present a complete collection, subject to certain definitions and exceptions which will be mentioned later, of all the best extant Greek Epigrams. Although many epigrams not given here have in different ways a special interest of their own, none, it is hoped, have been excluded which are of the first excellence in any style. But, while it would be easy to agree on three-fourths of the matter to be included in such a scope, perhaps hardly any two persons would be in exact accordance with regard to the rest; with many pieces which lie on the border line of excellence, the decision must be made on a balance of very slight considerations, and becomes in the end one rather of personal taste than of any fixed principle. For the Greek Anthology proper, use has chiefly been made of the two ∗PDF created by pdfbooks.co.za 1 great works of Jacobs, -

Female Improvisational Poets: Challenges and Achievements in the Twentieth Century

FEMALE .... improvisational - ,I: t -,· POETS ...~1 Challenges and Achievements in the Twentieth Century In December 2009, 14,500 people met at the Bilbao Exhibi tion Centre in the Basque Country to attend an improvised poetry contest.Forty-four poets took part in the 2009 literary tournament, and eight of them made it to the final. After a long day of literary competition, Maialen Lujanbio won and received the award: a big black txapela or Basque beret. That day the Basques achieved a triple triumph. First, thou sands of people had gathered for an entire day to follow a lite rary contest, and many more had attended the event via the web all over the world. Second, all these people had followed this event entirely in Basque, a language that had been prohi bited for decades during the harsh years of the Francoist dic tatorship.And third, Lujanbio had become the first woman to win the championship in the history of the Basques. After being crowned with the txapela, Lujanbio stepped up to the microphone and sung a bertso or improvised poem refe rring to the struggle of the Basques for their language and the struggle of Basque women for their rights. It was a unique moment in the history of an ancient nation that counts its past in tens of millennia: I remember the laundry that grandmothers of earlier times carried on the cushion [ on their heads J I remember the grandmother of old times and today's mothers and daughters.... • pr .. Center for Basque Studies # avisatiana University of Nevada, Reno ISBN 978-1-949805-04-8 90000 9 781949 805048 ■ .~--- t _:~A) Conference Papers Series No. -

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy By Daniel Christopher Walin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald J. Mastronarde Professor Kathleen McCarthy Professor Emily Mackil Spring 2012 1 Abstract Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy by Daniel Christopher Walin Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation examines the often surprising role of the slave characters of Greek Old Comedy in sexual humor, building on work I began in my 2009 Classical Quarterly article ("An Aristophanic Slave: Peace 819–1126"). The slave characters of New and Roman comedy have long been the subject of productive scholarly interest; slave characters in Old Comedy, by contrast, have received relatively little attention (the sole extensive study being Stefanis 1980). Yet a closer look at the ancestors of the later, more familiar comic slaves offers new perspectives on Greek attitudes toward sex and social status, as well as what an Athenian audience expected from and enjoyed in Old Comedy. Moreover, my arguments about how to read several passages involving slave characters, if accepted, will have larger implications for our interpretation of individual plays. The first chapter sets the stage for the discussion of "sexually presumptive" slave characters by treating the idea of sexual relations between slaves and free women in Greek literature generally and Old Comedy in particular. I first examine the various (non-comic) treatments of this theme in Greek historiography, then its exploitation for comic effect in the fifth mimiamb of Herodas and in Machon's Chreiai. -

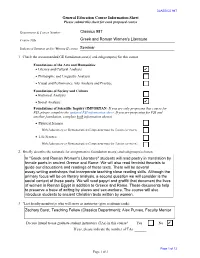

CLASSICS 98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please Submit This Sheet for Each Proposed Course

CLASSICS 98T General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Course Title Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities ñ Literary and Cultural Analysis ñ Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis ñ Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice Foundations of Society and Culture ñ Historical Analysis ñ Social Analysis Foundations of Scientific Inquiry (IMPORTAN: If you are only proposing this course for FSI, please complete the updated FSI information sheet. If you are proposing for FSI and another foundation, complete both information sheets) ñ Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) ñ Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs Page 1 of 12 Page 1 of 3 CLASSICS 98T 4. Indicate when do you anticipate teaching this course over the next three years: 2018-19 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2019-20 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 2020-21 Fall Winter Spring Enrollment Enrollment Enrollment 5. GE Course Units Is this an existing course that has been modified for inclusion in the new GE? Yes No If yes, provide a brief explanation of what has changed: Present Number of Units: Proposed Number of Units: 6. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has baan rapmducad from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from tha originalor copy submitiad. Thus, soma thesis and dissertation copies are in typawritar taca, while others may be from any type of computer printer. Tha quality of this reproduction Is dependant upon tha quality of tha copy subm itiad. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality iHustretions and photographs, print blaadthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can advarsaiy affect reproduction. In ttie unlikely event that the author did not serxl UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the delation. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from ieft to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quaiity 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Laaming 300 North Zaeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI’ TRANSATLANTIC DIALOGUES: POETRY OF ELIZABETH BISHOP AND WISLAWA SZYMBORSKA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Malgorzata J. Gabrys, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved By: Professor Jcredith Herrin, Adviser Professor Jim Phelan Adviser Professor Jessica Prinz Èbgfish Graduate Program UMI Number 9982562 UMI* UMI Micrororm9982562 Copyright 2000 by Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company. -

Here Walking Fossil Robert A

The Anticipation Hugo Committee is pleased to provide a detailed list of nominees for the 2009 Science Fiction and Fantasy Achievement Awards (the Hugos), and the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer (Sponsored by Dell Magazines). Each category is delineated to five nominees, per the WSFS Constitution. Also provided are the number of ballots with nominations, the total number of nominations and the number of unique nominations in each category. Novel The Last Centurion John Ringo 8 Once Upon a Time Philip Pullman 10 Ballots 639; Nominations: 1990; Unique: 335 The Mirrored Heavens David Williams 8 in the North Slow Train to Arcturus Dave Freer 7 To Hie from Far Cilenia Karl Schroeder 9 Little Brother Cory Doctorow 129 Hunter’s Run Martin Dozois Abraham 7 Pinocchio Walter Jon Williams 9 Anathem Neal Stephenson 93 Inside Straight George R. R. Martin 7 Utere Nihill Non Extra John Scalzi 9 The Graveyard Book Neil Gaiman 82 The Ashes of Worlds Kevin J Anderson 7 Quiritationem Suis Saturn’s Children Charles Stross 74 Gentleman Takes Sarah A Hoyt 7 Harvest James Van Pelt 9 Zoe’s Tale John Scalzi 54 a Chance The Inferior Peadar O’Guilin 7 Cenotaxis Sean Williams 9 Matter Iain M. Banks 49 Staked J.F. Lewis 7 In the Forests of Jay Lake 8 Nation Terry Pratchett 46 Graceling Kristin Cashore 6 the Night An Autumn War Daniel Abraham 46 Small Favor Jim Butcher 6 Black Petals Michael Moorcock 8 Implied Spaces Walter Jon Williams 45 Emissaries From Adam-Troy Castro 6 Political Science by Walton (Bud) Simons 7 Pirate Sun Karl Schroeder 41 the Dead & Ian Tregillis Half a Crown Jo Walton 38 A World Too Near Kay Kenyon 6 Mystery Hill Alex Irvine 7 Valley of Day-Glo Nick Dichario 35 Slanted Jack Mark L. -

Los Campos Literario Y De Poder En El Virreinato Del Perú: Los Escritos De Juan Del Valle Y Caviedes (1645-1697)

Los campos literario y de poder en el virreinato del Perú: Los escritos de Juan del Valle y Caviedes (1645-1697) A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures of the College of Arts and Sciences by Estela R. Roy-Alvarado M.A University of Northern Iowa November 2012 Committee Chair: Carlos M. Gutiérrez, Ph.D. ii Abstract This dissertation brings a new approach to Valle y Caviedes studies by using the theory of professional fields proposed by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, in conjunction with Norbert Elias’ work on court societies. Caviedes is considered the most significant satiric writer in the viceroyalty of Peru. His literary career is a crucial contribution to the Peruvian literary field of the 17th century and poses a particular interest regarding the relationship between the literary field and the field of power. My research focuses on Caviedes’ position in the colonial literary field as well as on his interaction with the colonial field of power in the viceroyalty of Peru in the 1600s. The origins of the colonial literary field coincided with a moment of cultural splendor in the metropolis and received the influence of the Spanish Golden Age transforming it into a literature that manifests its own concerns and interests. The viceroys, who sponsored poetic communities and academies, brought Spanish court culture to America. Accordingly, my work studies the relations between the writer and the court, as well as the cultural interaction between the viceroyalty and the metropolis.