Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Arguments

ORAL ARGUMENTS MINUTES OF THE PUBLIC SI'ITINGS held or the Peace Palace, The Hague, from 4 ro 26 Jurre 1973 FlRST PUBLIC SITTING (4 VI 73, 3 p.m.) Present: Presidenr LACHS;Vice-Presideitf AMMOUN;J~~dges FORSTER, GROS, BENGZON,PETRÉN, ONYEAMA, IGNACIO-PINTO, DE CASTRO,MOROZOV, JIMÉNEZ DE ARÉCHAGA,SIR Humphrey WALDOCK,NAGEKORA SINGE, RUDA; Ji~dge ad hoc Sir Muhammad ZAFRULLAKHAN; Regisrrar AOUARONE. Also preseitt: Far tlre Covernnlenr of Pokisran: H.E. Mr. J. G. Kharas, Ambassadorof Pakistan to IheNetherlands, as Agent; Mr. S. T. Joshua, Secretary of Embassy, as Deputy-Agent; Mr. Yahya Bakhtiar, Attorney-General of Pakistan. as Clrief Counsel; Mr. Zahid Said, Deputy Legal Adviser, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Govern- ment of Pakistan, as Cowtsel. PAKISTANI PRISONERS OF WAR OPENING OF THE ORAL PROCEEDLNGS The PRESIDENT: The Court meets today to consider the request for the indication of interim measures of protection, under Article 41 of the Statute of the Court and Article 66 of the 1972 Rules of Court, filed by the Government of Pakistan on II May 1973, in the case concerning the Trial of Pakistani Prisoners of War, brought by Pakistan against India. The proceedings in this case were begun by an Application by the Govern- ment of Pakistan, filed in the Registry of the Court on 11 May 1973'. The Application founds the jurisdiction of the Court on Article IX of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948, generally known as "the~ ~ Genocide~ Convention". -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

Talking Pictures TV Highlights for Week Beginning Mon 21St December 2020 SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Christmas Week

Talking Pictures TV Highlights for week beginning www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Mon 21st December 2020 SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Christmas Week Monday 21st December 7:25am Tuesday 22nd December 4:20pm Escape By Night (1953) Man on the Run (1949) Crime. Director: John Gilling. Crime Drama. Director: Lawrence Stars: Bonar Colleano, Sid James, Huntington. Stars: Valentine Dyall, Andrew Ray, Ted Ray, Simone Silva. Derek Farr and Leslie Perrins. Having An ace reporter with a drinking deserted the army, Peter Burdon is problem tracks a gangster on the run. continually on the run. Monday 21st December 9am and Tuesday 22nd December 6:50pm Wednesday 23rd December 4:30pm The Night My Number Came Up Stars, Cars & Guitars (1955) Talking Christmas – Mystery. Director: Leslie Norman. a Talking Pictures TV Exclusive! Stars: Michael Redgrave, Sheila Sim, Singer Tony Hadley, legendary Denholm Elliott and Alexander Knox. rock guitarist Jim Cregan and The fate of a military aircraft may broadcaster Alex Dyke bring their depend on a prophetic nightmare. Stars, Cars, Guitars show to Talking Tuesday 22nd December 9pm Pictures TV for a Christmas special. Shout at the Devil (1976) They’re joined by guests Marty and War. Director: Peter R. Hunt. Kim Wilde, Suzi Quatro and Mike Read Stars: Lee Marvin, Roger Moore, for a nostalgic look back at Christmas Barbara Parkins, Ian Holm, in the fifties and sixties as well as live Reinhard Kolldehoff. An American performances and festive fun. ex-military man and a British aristocrat are partners in the ivory Monday 21st December 12:15pm trade. On the eve of World War I, and Christmas Eve 6:10am they join battle against a German Scrooge (1935) Commander and his men. -

Capital Punishment : Public Opinion and Abolition in Great Britain During the Twentieth Century Carol A

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 8-1982 Capital punishment : public opinion and abolition in Great Britain during the twentieth century Carol A. Ransone Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Ransone, Carol A., "Capital punishment : public opinion and abolition in Great Britain during the twentieth century" (1982). Master's Theses. Paper 882. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: PUBLIC OPINION AND ABOLITION IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE TWENTIETH CENTURY BY CAROL ANN RANSONE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR THE.DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AUGUST 1982 LIBRARY ~ UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND VIRGINIA CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: PUBLIC OPINION AND ABOLITION IN GREAT BRITAIN DURING THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by CAROL ANN RANSONE Approved by TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE e I I I e I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I iii Chapter I. BRIEF HISTORY OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT AND PUBLIC OPINION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Early Laws Requiring Capital Punishment Reform Movememt in the Nineteenth Century Initial Attempts to Abolish the Death Penalty Public Opinion in the 1920's Formation of Reform Organizations Abolition Efforts Following World War II Position Taken by Prominent Personalities Efforts to Abolish Capital Punishment in the 1950's Change Brought by Homicide Act of 1957 Statistics Relative to Murder _ Introduction of Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Bill II. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY This biography aims to list the major sources of information about the history of the British Liberal, Social Democrat and Liberal Democrat parties. It concentrates on published books. Some references are made to archival sources for major figures but a guide to archive sources can be found elsewhere on the website and the books listed will guide towards collections of articles. It is organised in four sections: § The philosophic and policy background § The history of the party and Liberal governments § Elections § Biographies and autobiographies of leading party members The list does not attempt to be comprehensive but most of the major works included in this list will contain references to other relevant works. Those new to the subject are referred to our shorter reading list for an introduction to the subject. Unless otherwise indicated, the place of publication is usually London. THE PHILOSOPHIC AND POLICY BACKGROUND GENERAL R Bellamy, Liberalism and Modern Society: An Historic Argument, (Cambridge University Press, 1992) Duncan Brack and Tony Little (eds) Great Liberal Speeches (Politico’s Publishing, 2001) Duncan Brack & Robert Ingham (eds) Dictionary of Liberal Quotations (Politico’s Publishing, 1999) Alan Bullock (ed), The Liberal Tradition from Fox to Keynes, (Oxford University Press, 1967). Robert Eccleshall (ed) British Liberalism: Liberal thought from the 1640s to 1980s (Longman, 1986) S Maccoby (ed), The English Radical Tradition 1763-1914, (1952) Conrad Russell An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Liberalism (Duckworth, -

The Parliament (No. 2) Bill: Victim of the Labour

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL The Parliament (No. 2) Bill: Victim of the Labour Party's Constitutional Conservatism? being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Lavi David Green B.A. (Hons), M.A. September 2019 That a major bill to remove hereditary peers, and to reconstitute the basis of membership for the upper House, should have received all-party endorsement, been introduced as a Government bill, received a comfortable majority at second reading, then been abandoned in committee, was remarkable. Donald Shell1 The idea of reducing its powers was, in a vague kind of way, official Labour policy. What I was primarily concerned with, however, was to place its composition on a rational footing. Such a project, one might think, would commend itself to all Liberals and Socialists, if it involved eliminating or at least much reducing the hereditary element … In fact, the position was, from the beginning and throughout, much more complex. Lord Longford2 1 D. Shell (2006) ‘Parliamentary Reform’ in P. Dorey (ed.) The Labour Governments 1964–1970, Lon- don: Routledge, p.168 2 F. Longford (1974) The Grain of Wheat, London: Collins, pp.33-4 ABSTRACT This thesis assesses the failure of the UK House of Commons to pass an item of legislation: the Parliament (No. 2) Bill 1968. The Bill was an attempt by the Labour Government 1964- 70 at wholesale reform of the House of Lords. Government bills would normally pass without difficulty, but this Bill had to be withdrawn by the Government at the Committee Stage in the Commons. -

BRITISH COUNTERINSURGENCY in CYPRUS, ADEN, and NORTHERN IRELAND Brian Drohan a Dissertation Submitted to the Facu

RIGHTS AT WAR: BRITISH COUNTERINSURGENCY IN CYPRUS, ADEN, AND NORTHERN IRELAND Brian Drohan A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Susan D. Pennybacker Wayne E. Lee Klaus Larres Cemil Aydin Michael C. Morgan © 2016 Brian Drohan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Brian Drohan: Rights at War: British Counterinsurgency in Cyprus, Aden, and Northern Ireland (Under the direction of Susan D. Pennybacker) This study analyzes the role of human rights activism during three post-1945 British counterinsurgency campaigns in Cyprus (1955-1959), Aden (1963-1967), and the Northern Ireland “Troubles” (emphasizing 1969-1976). Based on material gathered from 15 archives in four countries as well as oral history records and personal papers, this study demonstrates that human rights activism shaped British operational decisions during each of these conflicts. Activists mobilized ideas of human rights to restrain counterinsurgency violence by defining certain British actions as illegal or morally unjustifiable. Although British forces often prevented activists from restraining state violence, activists forced government officials and military commanders to develop new ways of covering up human rights abuses. Focusing the analytical lens on activists and the officials with whom they interacted places rights activists on the counterinsurgency “battlefield” -

1 Hp0103 Roy Ward Baker

HP0103 ROY WARD BAKER – Transcript. COPYRIGHT ACTT HISTORY PROJECT 1989 DATE 5th, 12th, 19th, 26th, October and 6th November 1989. A further recording dated 16th October 1996 is also included towards the end of this transcript. Roy Fowler suggests this was as a result of his regular lunches with Roy Ward Baker, at which they decided that some matters covered needed further detail. [DS 2017] Interviewer Roy Fowler [RF]. This transcript is not verbatim. SIDE 1 TAPE 1 RF: When and where were you born? RWB: London in 1916 in Hornsey. RF: Did your family have any connection with the business you ultimately entered? RWB: None whatsoever, no history of it in the family. RF: Was it an ambition on your part or was it an accidental entry eventually into films? How did you come into the business? RWB: I was fairly lucky in that I knew exactly what I wanted to do or at least I thought I did. At the age of something like fourteen I’d had rather a chequered upbringing in an educa- tional sense and lived in a lot of different places. I had been taken to see silent movies when I was a child It was obviously premature because usually I was carried out in scream- ing hysterics. There was one famous one called The Chess Player which was very dramatic and German and all that. I had no feeling for films. I had seen one or two Charlie Chaplin films which people showed at children's parties in those days on a 16mm projector. -

Liberal Post-War By-Elections the Inverness Turning Point

LIBERAL POST-WAR BY-ELECTIONS THE INVERNESS TURNING POINT The by-election HE 1951 election is widely broad front of 475 in 1950, inevi- accepted as the low point tably meant a drastic reduction victories at Torrington in Liberal general elec- in the total number of votes in 1958 and Orpington tion performance. It cast for the party. The Liberals’ saw the party’s lowest share of the vote collapsed to in 1962 confirmed Tshare of the total vote, lowest 2.5 per cent, down from 9.1 per that the Liberal Party’s number of candidates and a fall cent in 1950. The party polled in the number of MPs elected only 730,556 votes, compared to recovery from its to its lowest level at a general 2,621,548 in 1950. election.1 At the following gen- The most high-profile casu- low point of the 1951 eral election in 1955 the average alty among the Liberal MPs at general election – only share of the vote per Liberal the 1951 election was the party’s candidate increased slightly, to Deputy Leader, Megan Lloyd about a hundrded 15.1 per cent from 14.7 per cent. George, who lost Anglesey to candidates, only six Fewer deposits were lost in 1955, Labour by 595 votes, after hav- despite an increase of one in ing represented the constitu- of whom were elected the number of candidates. All ency without a break since 1929. – was under way. But six Liberal MPs who fought the Emrys Roberts lost Merioneth, 1955 election were returned – the also to Labour. -

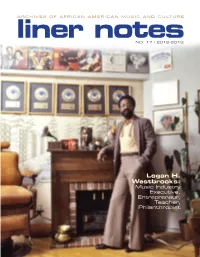

Liner Notes, No. 17

ARCHIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC AND CULTURE liner notes NO. 17 / 2012-2013 Logan H. Westbrooks: Music Industry Executive, Entrepreneur, Teacher, Philanthropist aaamc liner notes 17 121712.indd 1 12/21/12 10:52 AM aaamc mission From the Desk of the Director The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, preservation, and Since 2010, the AAAMC has been (sub-distributors or wholesalers), while dissemination of materials for involved in a documentation and oral record retail outlets, management and the purpose of research and history project that preserves the legacy concert promotion agencies, music study of African American of African American pioneers who industry publications, and other music and culture. established and became executives of related businesses proliferated. African www.indiana.edu/~aaamc black music divisions at major record Americans also purchased radio and companies, as well as others who have television stations and expanded local driven the success of independent and syndicated programs featuring record companies specializing in black music. Operating as a collective, black music. This project builds upon these entrepreneurs, along with their Table of Contents research I began in the early 1980s while white counterparts, moved black music attending conventions of the Black from the racial margins of society into From the Desk of Music Association, Jack the Rapper, and the mainstream, which contributed the Director ..................... 2 Black Radio Exclusive, which featured to the growth of a multibillion dollar seminars on a range of related topics. industry. Kenny Gamble, chairman In the Vault: These conventions and my interviews of Philadelphia International Records with industry pioneers (available as part and co-founder of the Black Music Recent Donations ............ -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 NOV/DEC 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 NOV/DEC 2020 Virgin 445 You can call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hello everyone and welcome to all our new supporters who bought the fantastic TPTV 2021 calendar – welcome to the Talking Pictures TV & Renown Pictures monthly newsletter, the largest free club supporting film and TV history! Talking of calendars – we have just a few left, so please do get your orders in quick as ‘Every Home Should Have One’ and they really do help us, plus they make the perfect gift for film buffs! This month we bring you a very special limited edition DVD release of SCROOGE (1951), with the wonderful Alastair Sim CBE, (in our opinion the best Scrooge on film), with optional subtitles for the very first time! It’s a 2-DVD special edition for Dickens’ 150th anniversary. Included on the discs are the original 1951 theatrical trailer and Scrooge (1935) with Seymour Hicks. It’s limited stock with a special price of just £15 with free UK postage (more details over the page). Keeping the Scrooge theme in mind, I’ve made some delightful exclusive baubles, see page 8, perfect for those ‘Bah Humbugs’ (I’m sure we all know one!)… By popular request, I’ve also made some cufflinks this month, see pages 26-27 for the designs. We have a host of special offers to help you with gifting this year, so I do hope you find something of interest. Look out for the BFI 2-DVD box set Stop! Look! Listen! on page 14, featuring nostalgic films on road safety. -

Robert Hartford-Davis and British Exploitation Cinema of the 1960S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository Corrupted, Tormented and Damned: Reframing British Exploitation Cinema and The films of Robert Hartford-Davis This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Michael Ahmed, M.A., B.A. PhD University of East Anglia Faculty of Film and Television Studies January 2013 Abstract The American exploitation film functioned as an alternative to mainstream Hollywood cinema, and served as a way of introducing to audiences shocking, controversial themes, as well as narratives that major American studios were reluctant to explore. Whereas American exploitation cinema developed in parallel to mainstream Hollywood, exploitation cinema in Britain has no such historical equivalent. Furthermore, the definition of exploitation, in terms of the British industry, is currently used to describe (according to the Encyclopedia of British Film) either poor quality sex comedies from the 1970s, a handful of horror films, or as a loosely fixed generic description dependent upon prevailing critical or academic orthodoxies. However, exploitation was a term used by the British industry in the 1960s to describe a wide-ranging and eclectic variety of films – these films included, ―kitchen-sink dramas‖, comedies, musicals, westerns, as well as many films from Continental Europe and Scandinavia. Therefore, the current description of an exploitation film in Britain has changed a great deal from its original meaning.