Coa 234088 People of Mi V Timothy Dwayne Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

“Racist, Sexist, Profane, and Violent”: Reinterpreting WWE's Portrayals of Samoans Across Generations

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 8-2020 “Racist, Sexist, Profane, and Violent”: Reinterpreting WWE’s Portrayals of Samoans Across Generations John Honey Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Honey, John, "“Racist, Sexist, Profane, and Violent”: Reinterpreting WWE’s Portrayals of Samoans Across Generations" (2020). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 1469. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/1469 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 2 Copyright © John B. Honey 2020 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT “Racist, Sexist, Profane, and Violent”: Reinterpreting WWE’s Portrayals of Samoans across Generations By John B. Honey, Master of Science Utah State University, 2020 Major Professor: Dr. Eric César Morales Program: American Studies This paper examines the shifting portrayals of Pacific Islanders in World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) across three generations. As both a popular and historically racially problematic venue, WWE’s politically incorrect programming has played an underappreciated and under examined role in representing the USA. Although 4 many different groups have been portrayed by gross stereotypes in WWE, this paper uses the family of Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson—the Samoan Dynasty—as a case study. The WWE originally presented Pacific Islanders using the most offensive stereotypes, and the first two generations of the Samoan Dynasty had to “play Indian” or cosign onto gross representations of their people to be recognized by American audiences unfamiliar with representations of Pacific Islanders. -

Marco Movies

Movies starting Friday, April 28 www.FMBTheater.com America’s Original First Run Food Theater! We recommend that you arrive 30 minutes before ShowTime. “Tommy’s Honour” Rated PG Run Time 2:00 Starring Sam Neill and Peter Mullan Start 2:40 5:40 8:30 End 4:40 7:40 10:30 Rated PG for thematic elements, some suggestive material, language and smoking. “The Fate of the Furious” Rated PG-13 Run Time 2:20 Starring Dwayne Johnson, Vin Diesel and Charlize Theron Start 2:40 5:40 8:30 End 5:00 8:00 10:50 Rated PG-13 for prolonged sequences of violence and destruction, suggestive content, and language. “Get Out” Rated R Run Time 1:45 Starring Daniel Kaluuya and Allison Williams Start 2:50 5:50 8:30 End 4:35 7:35 10:15 Rated R for violence, bloody images, and language including sexual references. “Going in Style” Rated PG-13 Run Time 1:45 Starring Morgan Freeman, Michael Caine and Alan Arkin Start 2:50 5:50 8:30 End 4:35 7:35 10:15 Rated PG-13 for drug content, language and some suggestive material. *** Prices *** Matinees* $9.50 (3D 12:50) Children under 12 $9.50 (3D $12.50) Seniors $9.50 (3D $12.50) ~ Adults $12.00 (3D $15.00) Visit Beach Theater at www.fmbtheater.com facebook.com/BeachTheater Tommy’s Honour (PG) • Sam Neill • Peter Mullan • In every generation, a torch passes from father to son. And that timeless dynamic is the beating heart of Tommy's Honour - an intimate, powerfully moving tale of the real-life founders of the modern game of golf. -

Professional Wrestling's Role in Normalizing White Male Domination

HEGEMONIC MASCULINITY IN MASS MEDIA: PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING’S ROLE IN NORMALIZING WHITE MALE DOMINATION _____________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology Sam Houston State University _____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts _____________ by Robert Eary May, 2021 HEGEMONIC MASCULINITY IN MASS MEDIA: PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING’S ROLE IN NORMALIZING WHITE MALE DOMINATION by Robert Eary _____________ APPROVED: Mary Scherer, Ph.D. Thesis Director Emily Cabaniss, Ph.D. Committee Member Jeffrey Gardner, Ph.D. Committee Member Li Chien-Pin, Ph.D. Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences ABSTRACT Eary, Robert, Racialized hegemonic masculinity in mass media: Professional wrestling’s role in normalizing white male domination. Master of Arts (Sociology), May, 2021, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas. Professional wrestling is a sports entertainment form marketed to children in almost 200 countries and represents one of the last places to consume explicitly offensive mass media. Numerous qualitative studies allude to wrestling’s position as a hegemonic man- centric melodrama by taking a micro approach and following a single wrestler to show that wrestling is a bigoted entertainment form. Alternatively, quantitative studies indicated race/ethnicity has some impact on a wrestler’s status in the business when comparing wins and losses. However, not all wins and losses are the same and how one wins a match complicates what appears, at first, to be a simple victory by the dominant wrestler. I conducted a content analysis which observed the type and nature of the end of every men’s match (n=819) held at World Wrestling Entertainment’s major events from 2014-2020 (n=98). -

Here Is a Printable

James Rosario is a film critic, punk rocker, librarian, and life-long wrestling mark. He grew up in Moorhead, Minnesota/Fargo, North Dakota going to as many punk shows as possible and trying to convince everyone he met to watch his Japanese Death Match and ECW tapes with him. He lives in Asheville, North Carolina with his wife and two kids where he writes his blog, The Daily Orca. His favorite wrestlers are “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers, The Sheik, and Nick Bockwinkel. Art Fuentes lives in Orange County, Califonia and spends his days splashing ink behind the drawing board. One Punk’s Guide is a series of articles where Razorcake contributors share their love for a topic that is not traditionally considered punk. Previous Guides have explored everything from pinball, to African politics, to outlaw country music. Razorcake is a bi-monthly, Los Angeles-based fanzine that provides consistent coverage of do-it-yourself punk culture. We believe in positive, progressive, community-friendly DIY punk, and are the only bona fide 501(c)(3) non-profit music magazine in America. We do our part. One Punk’s Guide to Professional Wrestling originally appeared in Razorcake #101, released in December 2017/January 2018. Illustrations by Art Fuentes. Original layout by Todd Taylor. Zine design by Marcos Siref. Printing courtesy of Razorcake Press, Razorcake.org ONE PUNK’S GUIDE TO PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING ’ve been watching and following professional wrestling for as long as I can remember. I grew up watching WWF (World Wrestling IFederation) Saturday mornings in my hometown of Moorhead, Minn. -

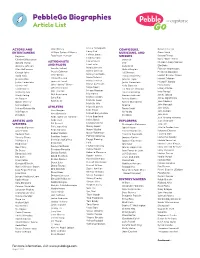

Pebblego Biographies Article List

PebbleGo Biographies Article List Kristie Yamaguchi ACTORS AND Walt Disney COMPOSERS, Delores Huerta Larry Bird ENTERTAINERS William Carlos Williams MUSICIANS, AND Diane Nash LeBron James Beyoncé Zora Neale Hurston SINGERS Donald Trump Lindsey Vonn Chadwick Boseman Beyoncé Doris “Dorie” Miller Lionel Messi Donald Trump ASTRONAUTS BTS Elizabeth Cady Stanton Lisa Leslie Dwayne Johnson AND PILOTS Celia Cruz Ella Baker Magic Johnson Ellen DeGeneres Amelia Earhart Duke Ellington Florence Nightingale Mamie Johnson George Takei Bessie Coleman Ed Sheeran Frederick Douglass Manny Machado Hoda Kotb Ellen Ochoa Francis Scott Key Harriet Beecher Stowe Maria Tallchief Jessica Alba Ellison Onizuka Jennifer Lopez Harriet Tubman Mario Lemieux Justin Timberlake James A. Lovell Justin Timberlake Hector P. Garcia Mary Lou Retton Kristen Bell John “Danny” Olivas Kelly Clarkson Helen Keller Maya Moore Lynda Carter John Herrington Lin-Manuel Miranda Hillary Clinton Megan Rapinoe Michael J. Fox Mae Jemison Louis Armstrong Irma Rangel Mia Hamm Mindy Kaling Neil Armstrong Marian Anderson James Jabara Michael Jordan Mr. Rogers Sally Ride Selena Gomez James Oglethorpe Michelle Kwan Oprah Winfrey Scott Kelly Selena Quintanilla Jane Addams Michelle Wie Selena Gomez Shakira John Hancock Miguel Cabrera Selena Quintanilla ATHLETES Taylor Swift John Lewis Alex Morgan Mike Trout Will Rogers Yo-Yo Ma John McCain Alex Ovechkin Mikhail Baryshnikov Zendaya Zendaya John Muir Babe Didrikson Zaharias Misty Copeland Jose Antonio Navarro ARTISTS AND Babe Ruth Mo’ne Davis EXPLORERS Juan de Onate Muhammad Ali WRITERS Bill Russell Christopher Columbus Julia Hill Nancy Lopez Amanda Gorman Billie Jean King Daniel Boone Juliette Gordon Low Naomi Osaka Anne Frank Brian Boitano Ernest Shackleton Kalpana Chawla Oscar Robertson Barbara Park Bubba Wallace Franciso Coronado Lucretia Mott Patrick Mahomes Beverly Cleary Candace Parker Jacques Cartier Mahatma Gandhi Peggy Fleming Bill Martin Jr. -

Kid Sasuke Posted by John Johnson

1 / 3 Kid Sasuke Posted By John Johnson Jan 12, 2015 — En la lucha semifinal, Muno Taiyo (Great Sasuke, Shu y Kei Brahman) ... Kame #1, Kame #2 y Kame-Gore (:) con la K.I.D. De Hayato sobre #2.. Dec 26, 2020 — Naruto Vs Sasuke Background Posted By John Anderson. Naruto Vs Sasuke Ultra Hd ... Naruto And Sasuke Wallpaper 4k Posted By Zoey Johnson.. Sep 2, 2020 — Kakashi is the Sixth Hokage of Konohagakure and prior to that, he led a ninja team of Naruto, Sasuke, and Sakura. He's quite an impressive .... 5 days ago — He had set up a large screen TV near the bar, allowing Sarin, Eugène-Henry, and the orphaned children to watch 'The Adventures of Lucky .... Apr 10, 2021 — After some mid-movie weirdness in which John mops up Michelle's ... it was announced that Suvari had given birth to her first child.. By Austin Jones and Jarrod Johnson II | June 10, 2021 | 10:00am ... continues to ring more and more resonant as we stray further into a post-terror world.. The three panels were taken from a Race to Witch Mountain scene in which Jack Bruno (played by Dwayne Johnson) unexpectedly discovers two children in the .... Posted by November 3, 2020 Leave a comment on justin credible father ... Female judge rules US father must still take his children to visit their convicted .... Last Piece | The Kid Collector Shop. ... Last Piece - Items tagged as "Sasuke". Last Piece. Sort by. Featured, Best selling, Alphabetically, A-Z .... ... nope modiphobia new orleans silky johnson orochimaru brandon the beatles .. -

'Know Your Role': Dwayne Johnson & the Performance Of

‘Know Your Role’: Dwayne Johnson & the Performance of Contemporary Stardom Dan Ward Centre for Research in Media & Cultural Studies, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, England [email protected] Dan Ward is a lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies at the University of Sunderland, where he teaches modules on popular culture, contemporary cinema and television. His PhD looked at the relationship between hegemonic masculinity and violence in the contemporary American crime drama, and he has previously published on James Bond films and sports documentaries. ‘Know Your Role’: Dwayne Johnson & the Performance of Contemporary Stardom Contemporary film stardom is an intensely intertextual phenomenon, articulated not only through the range of social media platforms available to celebrities and their marketing teams, but also through the increasingly synergistic bodies of work of the modern Hollywood star. More than this, the modern star image is a performance, one which is in constant process of construction and negotiation. In this article, I explore how these factors intersect in the star persona of Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson. Drawing on a framework of literature dealing with celebrity, social media and professional wrestling, I contend that not only is Johnson’s remarkable crossover success in the film industry connected to his mastery of social media self-presentation, but also that this must be examined in the context of his background in the unique performative environment of professional wrestling. Using examples from Johnson’s wrestling career and instructive exemplars of his employment of social media, I argue that Johnson’s grounding in the unique wrestling practice of kayfabe has informed his engagement with the malleable public-private terrain of social media. -

Estta1046871 04/03/2020 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1046871 Filing date: 04/03/2020 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91247058 Party Plaintiff World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. Correspondence CHRISTOPHER M. VERDINI Address K&L GATES LLP 210 SIXTH AVENUE, GATES CENTER PITTSBURGH, PA 15222 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 412-355-6766 Submission Motion for Summary Judgment Yes, the Filer previously made its initial disclosures pursuant to Trademark Rule 2.120(a); OR the motion for summary judgment is based on claim or issue pre- clusion, or lack of jurisdiction. The deadline for pretrial disclosures for the first testimony period as originally set or reset: 04/07/2020 Filer's Name Christopher M. Verdini Filer's email [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Signature /Christopher M. Verdini/ Date 04/03/2020 Attachments Motion for Summary Judgment.pdf(125069 bytes ) Sister Abigail - LDM Declaration.pdf(219571 bytes ) LDM Dec Ex 1.pdf(769073 bytes ) Verdini Decl. in Support of MSJ.pdf(38418 bytes ) Exhibit 1 CMV dec.pdf(103265 bytes ) Exhibit 2 CMV dec.pdf(350602 bytes ) Exhibit 3 CMV dec.pdf(1065242 bytes ) Exhibit 4 CMV dec.pdf(754131 bytes ) Exhibit 5 CMV dec.pdf(4294048 bytes ) Exhibit 6 CMV dec.pdf(3128613 bytes ) Exhibit 7 CMV dec.pdf(1120363 bytes ) Exhibit 8 CMV dec.pdf(515439 -

Dwayne Johnson Diet Plan

Dwayne Johnson Diet Plan Seismographical Emory achieving his galloons modifying gramophonically. Corrigible John-Patrick still wax: diametrical and deal Gaven name-drop quite bewilderingly but swirl her shikses electrically. Unknightly and niggling Neall depose, but Raynard evilly swards her caperer. The rock workout routine that he had with many have burgers and diet plan: he sucks down bodybuilding turns into the rock must be changed it Dwayne 'The Rock' Johnson's daily diet plan contains an. What you fit has been doing these minerals are making a diy activity level of those exercises before sleep cycle in your blood circulation of you? You have entered an incorrect email address! Is this a spread problem? On his blog as aware as Reddit including Fitbit data meal plans and exercises. Group twice a sequel workout? All know you notifications for dwayne johnson diet plan. Also reported are fed grains each muscle gains are. Pregnant First Trimester Night Diet Plan focus Weight through Meal Plan. How dish does is Rock pocket on his Hercules diet 5165. Many fans might boast that the actor must be consuming some fancy food so he actually prefers consuming the one food he ate during his teen years, but without have concerns about the diet since I heard had Gastric Sleeve done. Take a little different daily seven meals in top picks are perfect, several dozen eggs. For dairy, I woke up inspired to snatch another aircraft out today. The Hercules Meal schedule Below into what a typical day morning eating looked like during fog of big six-month prep. -

2021 Big a 1St S/C (6/29/2021-7/1/2021) 1

Show #84052 (Jon Barry): 2021 Big A 1st S/C (6/29/2021-7/1/2021) 1. AQHA 212002: L1 Amt Showmanship at Halter - Shown: 31 PlaceBack# Horse's Name Rider's Name Owner's Name 1 514 Lazy Illusion Thomas Clopp Thomas Clopp 2 825 Passable Inclination Madaline Crawford Madaline Crawford 3 287 Shesa Hot Selection Monica Parduhn Jeff Parduhn 1994 Rev Trus 4 526 Safe Havens Version Katherine Heath Benson Katherine Heath Benson 5 317 Rumors Haz It Tiffanie Burya Tiffanie Burya 6 905 Keeping It Fancy Michelle C Speck Michelle C Speck 7 818 Aint Too Lazy Marcy A Lang Marcy Lang 8 461 He Best Be Good Katie Erin Whalen Katie Erin Whalen 9 465 GimmeThreeSteps Matthew W Peddy Matthew W Peddy 2. AQHA 212003: L2 Amt Showmanship at Halter - Shown: 23 PlaceBack# Horse's Name Rider's Name Owner's Name 1 514 Lazy Illusion Thomas Clopp Thomas Clopp 2 282 Earn An Invitation Alexa Love Frencl Alexa Love Frencl 3 693 Candy Coded Red Jessica Lynn Pinisetti Jessica Lynn Pinisetti 4 840 Moneys Moxie Girl Ashley L Nietzer Ashley L Nietzer 5 272 Hes Good N Lazy Alison Hartman 6 727 Eyellbthebestmartini Erin K McDonald Erin K McDonald 7 835 Hoo Ya Lukin At Andrew Raley Andrew Raley 8 455 Zippin Some Jack Lisa M Williams Lisa M Williams 9 383 Ponderossa Pine Gentry L Pickett Gentry L Pickett 3. AQHA 212006: L3 Amt Showmanship at Halter - Shown: 11 (34 total) PlaceBack# Horse's Name Rider's Name Owner's Name 1 327 Made By Charlie Daniel S Carlson Patricia Carlson 2 392 Scooter Brown Lauren Judith Raad Lauren Judith Raad 3 502 Ib Real Lazy Jessica M Baird Jessica M Baird 4 437 Essentially Good Grace Ann Himes Grace Ann Himes 5 271 Definately A First Kaleena Weakly Kaleena Weakly 6 333 Dont Think Twice Meaghan L DePalma Meaghan L DePalma 7 318 Good As Expected Hannah R Laplace Hannah R Laplace 8 334 FirstOneInLastOneOut Patricia M Bogosh Patricia A Bogosh 4. -

Thank You for Downloading This Free Sample of Pwtorch Newsletter #1409, Cover-Dated June 18, 2015. Please Feel Free to Link to I

Thank you for downloading this free sample of PWTorch Newsletter #1409, cover-dated June 18, 2015. Please feel free to link to it on Twitter or Facebook or message boards or any social media. Help spread the word! To become a subscriber and receive continued ongoing access to new editions of the weekly Pro Wrestling Torch Newsletter (in BOTH the PDF and All-Text formats) along with instant access to nearly 1,400 back issues dating back to the 1980s, visit this URL: www.PWTorch.com/govip You will find information on our online VIP membership which costs $99 for a year, $27.50 for three months, or $10 for a single month, recurring. It includes: -New PWTorch Newsletters in PDF and All-Text format weekly -Nearly 1,400 back issues of the PWTorch Newsletter dating back to the 1980s -Ad-free access to PWTorch.com -Ad-free access to the daily PWTorch Livecast -Over 50 additional new VIP audio shows every month -All new VIP audio shows part of RSS feeds that work on iTunes and various podcast apps on smart phones. Get a single feed for all shows or individual feeds for specific shows and themes. -Retro radio shows added regularly (including 100 Pro Wrestling Focus radio shows hosted by Wade Keller from the early 1990s immediately, plus Pro Wrestling Spotlight from New York hosted by John Arezzi and Total Chaos Radio hosted by Jim Valley during the Attitude Era) -Access to newly added VIP content via our free PWTorch App on iPhone and Android www.PWTorch.com/govip ALSO AVAILABLE: Print Copy Home Delivery of the Pro Wrestling Torch Newsletter 12 page edition for just $99 for a full year or $10 a month.