RECREATING the CITADEL Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute 1975-77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Bahman Jalali1

11 Interview with Bahman Jalali1 By Catherine David2 Catherine David: Among all the Muslim countries, it seems that it was in Iran where photography was first developed immediately after its invention – and was most inventive. Bahman Jalali: Yes, it arrived in Iran just eight years after its invention. Invention is one thing, what about collecting? When did collecting photographs beyond family albums begin in Iran? When did gathering, studying and curating for archives and museum exhibitions begin? When did these images gain value? And when do the first photography collections date back to? The problem in Iran is that every time a new regime is established after any political change or revolution – and it has been this way since the emperor Cyrus – it has always tried to destroy any evidence of previous rulers. The paintings in Esfahan at Chehel Sotoon3 (Forty Pillars) have five or six layers on top of each other, each person painting their own version on top of the last. In Iran, there is outrage at the previous system. Photography grew during the Qajar era until Ahmad Shah Qajar,4 and then Reza Shah5 of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah held a grudge against the Qajars and so during the Pahlavi reign anything from the Qajar era was forbidden. It is said that Reza Shah trampled over fifteen thousand glass [photographic] plates in one day at the Golestan Palace,6 shattering them all. Before the 1979 revolution, there was only one book in print by Badri Atabai, with a few photographs from the Qajar era. Every other photography book has been printed since the revolution, including the late Dr Zoka’s7 book, the Afshar book, and Semsar’s book, all printed after the revolution8. -

Iran Business Guide

Contents Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines The Islamic Republic of IRAN BUSINESS GUIDE Edition 2011 By: Ramin Salehkhoo PB Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines Iran Business Guide 1 Contents Publishing House of the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines Iran Business Guide Edition 2011 Writer: Ramin Salehkhoo Assisted by: Afrashteh Khademnia Designer: Mahboobeh Asgharpour Publisher: Nab Negar First Edition Printing:June 2011 Printing: Ramtin ISBN: 978-964-905541-1 Price: 90000 Rls. Website: www.iccim.ir E-mail: [email protected] Add.: No. 175, Taleghani Ave., Tehran-Iran Tel.: +9821 88825112, 88308327 Fax: + 9821 88810524 All rights reserved 2 Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines Iran Business Guide 3 Contents Acknowledgments The First edition of this book would not have been possible had it not been for the support of a number of friends and colleagues of the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines, without whose cooperation, support and valuable contributions this edition would not have been possible. In particular, the Chamber would like to thank Mrs. M. Asgharpour for the excellent job in putting this edition together and Dr. A. Dorostkar for his unwavering support . The author would also like to thank his family for their support, and Mrs. A. Khademia for her excellent assistance. Lastly, the whole team wishes to thank H.E. Dr. M. Nahavandian for his inspiration and guidance. Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines June 2011 2 Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines Iran Business Guide 3 -

KGE Prostitute Tate Press Release2 14.11.17.Pages

Kaveh Golestan Estate Press Release: Kaveh Golestan at Tate Modern Kaveh Golestan at Tate Modern Kaveh Golestan Estate Vali Mahlouji / Archaeology of the Final Decade Kaveh Golestan Estate and Vali Mahlouji / Archaeology of the Final Decade (AOTFD) are delighted to announce the opening of a room at Tate Modern dedicated to Kaveh Golestan, featuring twenty vintage silver gelatin prints from the Prostitute series (1975-77). AOTFD’s curatorial and documentary material from Recreating the Citadel is displayed alongside the photographs. The display marks the first time in its history that Tate Modern has dedicated a room in its permanent collection to an Iranian artist for a period of a year. The Prostitute series had only ever been publicly exhibited for two weeks in 1978 until they were unearthed by Vali Mahlouji and exhibited at Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam (2014); Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (2014); MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome (2014-15); and Photo London (2015). AOTFD has also placed works by Kaveh Golestan at Musée d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). The curatorial and documentary materials discovered by AOTFD via Recreating the Citadel has shed new light upon historical facts about Tehran's former red light district, from its formation in the 1920s to its torching and subsequent forced destruction by religious decree in 1979. Notes for Editors Biography - Kaveh Golestan (1950-2003) Kaveh Golestan was an important and prolific Iranian pioneer of documentary photography. His photographic practice has hugely informed the work of future generations of Iranian artists, but until now remained seriously over-looked by institutions inside and outside of his home country. -

Longing to Return and Spaces of Belonging

TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS SERIAL B, HUMANIORA, 374 LONGING TO RETURN AND SPACES OF BELONGING. IRAQIS’ NARRATIVES IN HELSINKI AND ROME By Vanja La Vecchia-Mikkola TURUN YLIOPISTO UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Turku 2013 Department of Social Research/Sociology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Turku Turku, Finland Supervised by: Suvi Keskinen Östen Wahlbeck University of Helsinki University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland Helsinki, Finland Reviewed by: Marja Tiilikainen Marko Juntunen University of Helsinki University of Tampere Helsinki, Finland Helsinki, Finland Opponent: Professor Minoo Alinia Uppsala University Uppsala, Sweden ISBN 978-951-29-5594-7 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987 Acknowledgments First of all, I wish to express my initial appreciation to all the people from Iraq who contributed to this study. I will always remember the time spent with them as enriching and enjoyable experience, not only as a researcher but also as a human being. I am extremely grateful to my two PhD supervisors: Östen Wahlbeck and Suvi Keskinen, who have invested time and efforts in reading and providing feedback to the thesis. Östen, you have been an important mentor for me during these years. Thanks for your support and your patience. Your critical suggestions and valuable insights have been fundamental for this study. Suvi, thanks for your inspiring comments and continuous encouragement. Your help allows me to grow as a research scientist during this amazing journey. I am also deeply indebted to many people who contributed to the different steps of this thesis. I am grateful to both reviewers Marja Tiilikainen and Marko Juntunen, for their time, dedication and valuable comments. -

Protest Visual Arts in Iran from the 1953 Coup to the 1979 Islamic Revolution

International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 2020, 9, 285-299 285 Protest Visual Arts in Iran from the 1953 Coup to the 1979 Islamic Revolution Hoda Zabolinezhad1,* and Parisa Shad Qazvini2 1Phd in Visual Arts from University of Strasbourg, Post-Doc Researcher at Alzahra University of Tehran 2Assisstant Professor at Faculty of Arts, University of Alzahra of Tehran, Iran Abstract: There have been conducted a few numbers of researches with protest-related subjects in visual arts in a span between the two major unrests, the 1953 Coup and the 1979 Islamic Revolution. This study tries to investigate how the works of Iranian visual artists demonstrate their reactions to the 1953 Coup and progresses towards modernization that occurred after the White Revolution of Shāh in 1963. The advent of the protest concept has coincided with the presence of Modern and Contemporary art in Iran when the country was occupied by allies during the Second World War. The 1953 Coup was a significant protest event that motivated some of the artists to react against the monarchy’s intention. Although, poets, authors, journalists, and writers of plays were pioneer to combat dictatorship, the greatest modernist artists of that time, impressed by the events after the 1953 Coup, just used their art as rebellious manifest against the governors. Keywords: Iranian Visual Artists, Pahlavi, Political Freedom, Persian Protest Literature, the Shāh. INTRODUCTION Abrahamian 2018). The Iranian visual arts affected unconstructively by Pahlavi I (1926-1942) contradictory The authors decided to investigate the subject of approaches. By opening of Fine Arts School, which protest artworks because it is almost novel and has became after a while Fine Arts Faculty of the University addressed by the minority of other researchers so far. -

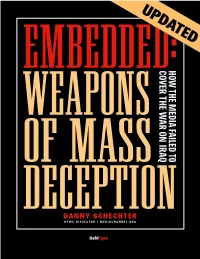

Weapons of Mass Deception

UPDATED. EMBEDDEDCOVER THE WAR ON IRAQ HOW THE TO MEDIA FAILED . WEAPONS OF MASS DECEPTIONDANNY SCHECHTER NEWS DISSECTOR / MEDIACHANNEL.ORG ColdType WHAT THE CRITICS SAID This is the best book to date about how the media covered the second Gulf War or maybe miscovered the second war. Mr. Schecchter on a day to day basis analysed media coverage. He found the most arresting, interesting , controversial, stupid reports and has got them all in this book for an excellent assessment of the media performance of this war. He is very negative about the media coverage and you read this book and you see why he is so negative about it. I recommend it." – Peter Arnett “In this compelling inquiry, Danny Schechter vividly captures two wars: the one observed by embedded journalists and some who chose not to follow that path, and the “carefully planned, tightly controlled and brilliantly executed media war that was fought alongside it,” a war that was scarcely covered or explained, he rightly reminds us. That crucial failure is addressed with great skill and insight in this careful and comprehensive study, which teaches lessons we ignore at our peril.” – Noam Chomsky. “Once again, Danny Schechter, has the goods on the Powers The Be. This time, he’s caught America’s press puppies in delecto, “embed” with the Pentagon. Schechter tells the tawdry tale of the affair between officialdom and the news boys – who, instead of covering the war, covered it up. How was it that in the reporting on the ‘liberation’ of the people of Iraq, we saw the liberatees only from the gunhole of a moving Abrams tank? Schechter explains this later, lubricious twist, in the creation of the frightening new Military-Entertainment Complex.” – Greg Palast, BBC reporter and author, “The Best Democracy Money Can Buy.” "I'm your biggest fan in Iraq. -

Press Release: Recreating the Citadel at Tate Modern

Archaeology of the Final Decade Press Release: Recreating the Citadel at Tate Modern Press Release: Recreating the Citadel at Tate Modern by Archaeology of the Final Decade Archaeology of the Final Decade (AOTFD) is delighted to announce the opening of a room dedicated to Recreating the Citadel: Prostitute (1975-77) at Tate Modern, featuring Kaveh Golestan’s photographic work alongside research materials uncovered by AOTFD. Following the recent acquisition of these materials by the museum, they will be displayed in parallel for the next twelve months within the museum’s permanent collection. The display marks the first time in the museum’s history that a room of the permanent collection has been dedicated to an Iranian artist. Tate’s recent acquisition of twenty vintage prints from Golestan’s Prostitute series comes on the back of recent travelling exhibitions of Recreating the Citadel, curated by AOTFD, at Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam, Musée d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo (Rome), and Photo London (Somerset House). Tate’s acquisition follows similar purchases of Golestan’s work by Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Founded by Vali Mahlouji in 2010, Archaeology of the Final Decade is a curatorial and educational platform which identifies, investigates and re-circulates significant cultural and artistic materials that have remained obscure, under-exposed, endangered, or in some instances destroyed. A core aim of AOTFD is the reintegration of these materials into cultural memory, counteracting the damages of censorship and historical erasure. -

Iran's War on Drugs

The Middle East Institute Policy Brief No. 3 December 2007 Iran’s War on Drugs: Holding the Line? Contents Drugs and Counter-drug Policies in Iran: A Brief Historical Excursion 1 By John Calabrese Iran and the Geometry of the Drug Trade 2 A Bleak Landscape: The Costs and Casualties 5 Executive Summary Iran’s National Drug Control Framework 7 Surging poppy cultivation in Afghanistan, besides having boosted Iran’s Regional and International Coop- significance as a drug transit state, has fuelled Iranian drug abuse and eration 13 addiction. In the words of Roberto Arbitrio, the head of the UNODC’s Tehran office, “Iran is the frontline of the war against drugs.” But hold- Continuing Challenges and Uncer- ing the line has proven exceedingly difficult and costly for Iran. To ad- tainties 16 dress this problem, Iranian officials have put in place aggressive law enforcement measures as well as progressive harm reduction interven- Concluding Thoughts 18 tions. Nevertheless, opiates smuggling persists, while abuse and addic- tion are rampant. For 60 years, the Middle East Institute has been dedicated to increasing Americans’ knowledge and understanding of the region. MEI offers program activities, media outreach, language courses, scholars and an academic journal to help achieve its goals. The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the About the Author Middle East in America and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. -

UNEDITED HISTORY Iran 1960 – 2014

UNEDITED HISTORY Iran 1960 – 2014 Sequences of modernity in Iran from 1960 to the present Over 200 works for the most part unseen in Italy, taking us through an exploration of Iran’s contemporary history from 1960 until today. A unique occasion to renew our look on this multi-layered history and culture that often attracts attention. December 11, 2014 – March 29, 2014 www.fondazionemaxxi.it Rome, 10 December 2014. Over 200 works, for the most part unseen in Italy, and more than 20 artists introducing us to more than half a century’s art and culture in Iran; a country often arousing attention and fascination while its complexities still need to be unfolded carefully. Here is the challenge raised by Unedited History. Iran 1960 – 2014, an exhibition conceived by the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, curated by Catherine David, Odile Burluraux, Morad Montazami, Narmine Sadeg, on the overall, and Vali Mahlouji for The Archaeology of the Final Decade section. The exhibition is jointly produced with MAXXI (December 11, 2014 – March 29, 2015). In the attempt to cross Iran’s modern visual culture, Unedited History offers us a renewal of our viewpoint on this country and of the preconceptions that need to be challenged through a critical approach. The premise of this historical journey does not believe in assembling and presenting a unitary history of Iranian modern art. But rather in engaging with its gaps, blind alleys and unresolved complexities, proceeding with a specific montage that holds together the contentious dimensions of a seemingly “unedited” History. -

Rouhani Declares Banking Reform to Spur Economy

Iran: Faisal’s attendance Economy minister Iran Greco-Roman wins Tehran gallery to 21112at MKO meeting signifies 4 apologizes on inflated Asian Cadet Wrestling showcase rarely-seen NATION Saudi stupidity ECONOMY salaries SPORTS Championship ART& CULTURE photos by Kaveh GGolestan WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y Newly appointed chief of staff elaborates on four-tier mission 2 12 Pages Price 10,000 Rials 38th year No.12595 Monday JULY 11, 2016 Tir 21, 1395 Shawwal 6, 1437 Iran: Faisal’s Rouhani declares banking attendance at MKO meeting signifies Saudi reform to spur economy stupidity ECONOMY TEHRAN — Banking re- Iranian calendar year, ending March 2017, to increase their ability in providing in the country’s monetary discipline, which deskform as the most impor- President Hassan Rouhani announced on domestic production units with more aims to improve the administration’s financial POLITICAL TEHRAN — An in- tant financial and monetary plan to foster Sunday. loans, Rouhani explained. transparency,” he said. deskformed source at economic growth will start in the current The plan seeks to enable banks “The banking reform plan is a turning point 4 the Iranian Foreign Ministry said on Sunday that Saudi Arabia uses ter- rorism against Muslim countries in the Middle East as an “instrument” to Mourning achieve its objectives. The comments by the Foreign Ministry source came as Prince Tur- crowds bid ki al-Faisal, Saudi Arabia’s former spy chief, attended an annual meeting of the MKO terrorist group in Paris on farewell Saturday during which he pledged to back the group. -

Derhc3bcseyinkc3b6se-Karaperde

HÜSEYİN KÖSE Mart 1970'te Gaziantep'te doğdu. 2003'te İstanbul Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi'nde Pierre Bourdieu üzerine hazırladığı teziyle doktorasını verdi. İletişimin kültürel boyutları, medya ve sinema sosyolojisi alanla rında çalışmaları bulunan Köse'nin yayımlanmış kitaplarından bazıları şunlar: Bourdieu Medyaya Karşı, Papirüs Yayınevi, İstanbul 2004; Med ya tik Pa radigma, Yirmidört Yayınevi, İstanbul 2006; Alternatif Medya , Yirmidört Yayınevi, İstanbul 2007; İletişimin Issızlaşması, Yirmidört Yayınevi, İstanbul, 2007; Medya ve Tüketim Sosyolojisi, Ayraç Yayınevi, Ankara, 2010; Medya Mahrem: Medya da Ma hremiyet Olgusu ve Tra ns paran Bir Ya şamdan Parçalar (ed.), Ayrıntı Yayınları, İstanbul, 2011; Planör Düşünce: Arkaik Dönemde ve Dijital Medya Çağında Ayla klık (ed.), Ayrıntı Yayınları, İstanbul, 2012; Eric Dacheux, Ka musal Alan (çeviri), Ayrıntı Yayınları, İstanbul, 2012. Ayrıntı: 765 Sinema Dizisi: 3 Kara Perde İran Yönetmen Sineması Üzerine Okumalar Hüseyin Köse Dizi Editörü Enis Rıza Sakızlı Düzelti Papatya Tıraşın © 2014, Hüseyin Köse Bu kitabın Türkçe yayım haklan Ayrıntı Yayınları'na aittir. Kapak Fotoğrafı Gergedan Mevsimi'nden Kapak Tasarımı Gökçe Alper Dizgi Esin Tapan Yetiş Baskı Kayhan Matbaacılık San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti. Davutpaşa Cad. Güven San. Sit. C Blok No.: 244 Topkapı!İst. Tel.: (0212) 612 31 85 Sertifika No.: 12156 Birinci Basım: İstanbul, 2014 Baskı Adedi 1000 ISBN 978-975-539-784-9 Sertifika No.: 10704 AYRINTI YAYINLARI Basım Dağıtım Tic. San. ve Ltd. Şti. Hobyar Malı. Cemal Nadir Sok. No.: 3 Cağaloğlu - İstanbul Tel.: (0212) 512 15 00 Faks: (0212) 512 15 11 www.ayrintiyayinlari.com.tr & [email protected] Derleyen Hüseyin Köse Kara Perde İran Yönetmen Sineması Üzerine Okumalar İçindekiler Önsöz ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 Birinci Perde: Sükut "Bize Bak!"/Seçil Büker ....................................................................................................................... -

Kaveh Golestan - the Citadel Foam Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam 21 March – 4 May 2014

Archaeology Agents Limited Flat 3, 57 Eaton Place, London SW1X 8DF www.archaeologyofthefinaldecade.com +447990575365 Kaveh Golestan - The Citadel Foam Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam 21 March – 4 May 2014 Kaveh Golestan - The Citadel is the first iteration of an ongoing curatorial and research project founded by Mahlouji entitled ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE FINAL DECADE. This larger project investigates cultural and artistic material which were destroyed, forgotten or under-represented and yet are historically significant from the final decade before 1979 - the pre-revolutionary moment - in Iran. By revisiting these sites of culture the project re-circulates and reincorporates the material back into cultural memory and discourse and restrospectively complexifies their compounded meanings. ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE FINAL DECADE aims to situate Golestan beyond photojournalism firmly within a museum and art historical context. Company registration Number 9825010. Registered address: Flat 3, 57 Eaton PlaCe, London SW1X 8DF, UK Kaveh Golestan (1950-2003) was an important and prolific Iranian documentary photographer and a pioneer of street photography. His photographic practice has hugely informed the work of future generations of Iranian artists but has remained seriously over-looked in Europe. Kaveh Golestan - The Citadel presents 45 vintage photographs from the series entitled Prostitute taken between 1975-1977 of women working in the Citadel of Shahr-e No, the red light district of Teheran. The photographs will be exhibited for the first time as a vintage set since 1978. Alongside the photographs, the exhibition includes original notebooks of Golestan, newspaper clippings and audio interviews relating to the area. The Citadel of Shahr-e No (literally translated as 'New Town') was an old walled neighbourhood in Tehran, which was accessed through a gate.