ROSEGOLESTAN Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Bahman Jalali1

11 Interview with Bahman Jalali1 By Catherine David2 Catherine David: Among all the Muslim countries, it seems that it was in Iran where photography was first developed immediately after its invention – and was most inventive. Bahman Jalali: Yes, it arrived in Iran just eight years after its invention. Invention is one thing, what about collecting? When did collecting photographs beyond family albums begin in Iran? When did gathering, studying and curating for archives and museum exhibitions begin? When did these images gain value? And when do the first photography collections date back to? The problem in Iran is that every time a new regime is established after any political change or revolution – and it has been this way since the emperor Cyrus – it has always tried to destroy any evidence of previous rulers. The paintings in Esfahan at Chehel Sotoon3 (Forty Pillars) have five or six layers on top of each other, each person painting their own version on top of the last. In Iran, there is outrage at the previous system. Photography grew during the Qajar era until Ahmad Shah Qajar,4 and then Reza Shah5 of the Pahlavi dynasty. Reza Shah held a grudge against the Qajars and so during the Pahlavi reign anything from the Qajar era was forbidden. It is said that Reza Shah trampled over fifteen thousand glass [photographic] plates in one day at the Golestan Palace,6 shattering them all. Before the 1979 revolution, there was only one book in print by Badri Atabai, with a few photographs from the Qajar era. Every other photography book has been printed since the revolution, including the late Dr Zoka’s7 book, the Afshar book, and Semsar’s book, all printed after the revolution8. -

Rokni Haerizadeh in Conversation with Sohrab Mohebbi

gather his followers and they would all read Rokni Haerizadeh poetry and drink and dance. When there were in conversation with electricity cuts, it would all happen by Sohrab Mohebbi candlelight. Those houses were part of an interior life that was so different from life outside. Sohrab: I feel like we shouldn’t talk about Tehran. Do you think we can talk about Tehran S: Yeah, your house represented that kind of today? interior life. It was more than just a place to party. Rokni: No, I don’t really think so. R: Right, it gave you relative freedom as S: We can’t, right? an artsy kid, in the way art can. It gave you the option to not be a player and to be R: I mean, what’s the point of talking about a little different. We were working toward it? It makes us sound like delusional old building something new, confronting and men.... It’s been so long since the two of us responding to society, being rebels, anar- have had a conversation in the first place. chists.... It also allowed us to exist We’ve both spent so much time trying to break uniquely as a group. There was this inside away from what we once were. What can those joke between us. Imagine you’re at a gather- memories do for us now? What good are they ing, and all of a sudden you go up to someone other than being very personal? Maybe what and whisper in his ear, “You see that guy we can talk about is the fact that we lived over there? He’s not my brother. -

Iran Business Guide

Contents Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines The Islamic Republic of IRAN BUSINESS GUIDE Edition 2011 By: Ramin Salehkhoo PB Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines Iran Business Guide 1 Contents Publishing House of the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines Iran Business Guide Edition 2011 Writer: Ramin Salehkhoo Assisted by: Afrashteh Khademnia Designer: Mahboobeh Asgharpour Publisher: Nab Negar First Edition Printing:June 2011 Printing: Ramtin ISBN: 978-964-905541-1 Price: 90000 Rls. Website: www.iccim.ir E-mail: [email protected] Add.: No. 175, Taleghani Ave., Tehran-Iran Tel.: +9821 88825112, 88308327 Fax: + 9821 88810524 All rights reserved 2 Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines Iran Business Guide 3 Contents Acknowledgments The First edition of this book would not have been possible had it not been for the support of a number of friends and colleagues of the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines, without whose cooperation, support and valuable contributions this edition would not have been possible. In particular, the Chamber would like to thank Mrs. M. Asgharpour for the excellent job in putting this edition together and Dr. A. Dorostkar for his unwavering support . The author would also like to thank his family for their support, and Mrs. A. Khademia for her excellent assistance. Lastly, the whole team wishes to thank H.E. Dr. M. Nahavandian for his inspiration and guidance. Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines June 2011 2 Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries & Mines Iran Business Guide 3 -

KGE Prostitute Tate Press Release2 14.11.17.Pages

Kaveh Golestan Estate Press Release: Kaveh Golestan at Tate Modern Kaveh Golestan at Tate Modern Kaveh Golestan Estate Vali Mahlouji / Archaeology of the Final Decade Kaveh Golestan Estate and Vali Mahlouji / Archaeology of the Final Decade (AOTFD) are delighted to announce the opening of a room at Tate Modern dedicated to Kaveh Golestan, featuring twenty vintage silver gelatin prints from the Prostitute series (1975-77). AOTFD’s curatorial and documentary material from Recreating the Citadel is displayed alongside the photographs. The display marks the first time in its history that Tate Modern has dedicated a room in its permanent collection to an Iranian artist for a period of a year. The Prostitute series had only ever been publicly exhibited for two weeks in 1978 until they were unearthed by Vali Mahlouji and exhibited at Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam (2014); Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (2014); MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, Rome (2014-15); and Photo London (2015). AOTFD has also placed works by Kaveh Golestan at Musée d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). The curatorial and documentary materials discovered by AOTFD via Recreating the Citadel has shed new light upon historical facts about Tehran's former red light district, from its formation in the 1920s to its torching and subsequent forced destruction by religious decree in 1979. Notes for Editors Biography - Kaveh Golestan (1950-2003) Kaveh Golestan was an important and prolific Iranian pioneer of documentary photography. His photographic practice has hugely informed the work of future generations of Iranian artists, but until now remained seriously over-looked by institutions inside and outside of his home country. -

Modernism in Iran:1958-1978 Colin Browne & Pantea Haghighi

In conversation: Modernism in Iran:1958-1978 Colin Browne & Pantea Haghighi Pantea Haghighi and Colin Browne met on June 20, 2018 to discuss Modernism in Iran: 1958-1978, which ran from January 26 to May 5, 2018 at Griffin Art Projects in North Vancouver, BC. Colin Browne: I’m speaking with Pantea Haghighi, owner and curator of Republic Gallery in Vancouver, BC, about an exhibition she organized recently entitled Modernism in Iran: 1958-1978. Would you be willing to describe it for us, along with your intentions? Pantea Haghighi: Sure. The exhibition featured works by Mohammad Ehsai, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, Mansour Ghandriz, Farideh Lashai, Sirak Melkonian, Bahman Mohasses, Faramarz Pilaram, Behjat Sadr, Parviz Tanavoli, Mohsen Vaziri-Moghaddam, and Charles Zenderoudi. These artists played an important role in establishing Modernism in Iran during the cultural renaissance that occurred between 1958 and 1978. In Iran, their work is referred to as Late Modernism. I decided to divide the gallery in half. On one side I placed the work of those artists who were exploring their national artistic identity, returning to old Persian motifs in order to identify with Modernism. On the other side, I placed the work of artists who were heavily influenced by Western art. When you entered the room, you were immediately aware of the two different expressions of Iranian Modernism. CB: I want to ask about the show, but let’s frst talk about what might be called Early Modernism in Iran. PH: Early Modernism dates from around 1940, when the School of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran opened. -

Art Abstrait & Contemporain

Art abstrait & contemporain - Drouot - Richelieu, salle 4, mercredi 11 juin 2014 Index des ArtIstes Dino ABIDINE 182 à 187 Gérard GASIOROWSKI 301 John NAPPER 96 Valentin AFANASSIEV 203 Jacques GERMAIN 65 Devrim NEJAD 163 à 166 Angel ALONSO 123 et 124 Léon GISCHIA 47 Leopoldo NOVOA 105 Antonio-Henrique AMARAL 110 Raymonde GODIN 97 et 98 Miguel OCAMPO 112 à 116 Willy ANTHOONS 136 Henri GOETZ 50 à 52 et 69 à 71 Ebrahim OLFAT 242 et 243 Farid AOUAD 244 et 245 GROUPE IRWIN 227 à 229 ORAZI 130 et 131 Avni ARBAS 188 Raymond HAINS 288 et 289 Carlos PAEZ-VILARO 106 et 107 ARMAN 291 à 293 Etienne HAJDU 224 Véra PAGAVA 204 Nasser ASSAR 237 Jean HéLION 49 Tseng-Ying PANG 262 Ragheb AYAD 235 Robert HELMAN 89 Max PAPART 76 André BEAUDIN 1 à 20 Charlotte HENSCHEL 133 Carl-Henning PEDERSEN 138 Abdallaha BENANTEUR 233 et 234 Daniel HUMAIR 303 Dario PEREZ-FLORES 108 Antonio BERNI 111 Ferit ISCAN 167 à 179 Henri Ernst PFEIFFER 134 Roger BEZOMBES 279 et 280 Zeki Faik IZER 192 Jean PIAUBERT 85 à 87 Roger BISSIèRE 57 Jean JANSEM 277 Alkis PIERRAKOS 150 à 156 Albert BITRAN 68 Dahai JIANG 261 Edgard PILLET 67 Francisco BORES 118 à 122 Ömer KALESI 180 Mario PRASSINOS 157 Bahman BOROJENI 240 et 241 Paul KALLOS 221 à 223 Bernard QUENTIN 63 Christine BOUMEESTER 60 Ida KARSKAYA 202 REINHOUD 137 Huguette CALAND 247 Théo KERG 143 Suzanne ROGER 21 à 45 Manuel CARGALEIRO 125 Eugène de KERMADEC 46 Behjat SADR 238 et 239 Moshé CASTEL 253 Ladislas KIJNO 64 Jean-Joseph SANFOURCHE 268 à 276 César Baldiccini dit CéSAR 290 Sigismond KOLOS-VARY 225 Maurice-Elie SARTHOU 77 et -

Longing to Return and Spaces of Belonging

TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS SERIAL B, HUMANIORA, 374 LONGING TO RETURN AND SPACES OF BELONGING. IRAQIS’ NARRATIVES IN HELSINKI AND ROME By Vanja La Vecchia-Mikkola TURUN YLIOPISTO UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Turku 2013 Department of Social Research/Sociology Faculty of Social Sciences University of Turku Turku, Finland Supervised by: Suvi Keskinen Östen Wahlbeck University of Helsinki University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland Helsinki, Finland Reviewed by: Marja Tiilikainen Marko Juntunen University of Helsinki University of Tampere Helsinki, Finland Helsinki, Finland Opponent: Professor Minoo Alinia Uppsala University Uppsala, Sweden ISBN 978-951-29-5594-7 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987 Acknowledgments First of all, I wish to express my initial appreciation to all the people from Iraq who contributed to this study. I will always remember the time spent with them as enriching and enjoyable experience, not only as a researcher but also as a human being. I am extremely grateful to my two PhD supervisors: Östen Wahlbeck and Suvi Keskinen, who have invested time and efforts in reading and providing feedback to the thesis. Östen, you have been an important mentor for me during these years. Thanks for your support and your patience. Your critical suggestions and valuable insights have been fundamental for this study. Suvi, thanks for your inspiring comments and continuous encouragement. Your help allows me to grow as a research scientist during this amazing journey. I am also deeply indebted to many people who contributed to the different steps of this thesis. I am grateful to both reviewers Marja Tiilikainen and Marko Juntunen, for their time, dedication and valuable comments. -

Kunsthalle Zürich Limmatstrasse 270 CH–8005 Zürich Ramin

Ramin Haerizadeh / Rokni Haerizadeh / Hesam Rahmanian Slice A Slanted Arc Into Dry Paper Sky** 21.02.–17.05.2015 Al Barsha Street in Dubai is where the three Iranian artists Ramin Haerizadeh (*1975), Rokni Haerizadeh (*1978) and Hesam Rahmanian (*1980) currently live. It is an extraordinary villa full of things, a studio, a stage, a film set and movie theatre; it is a cabinet of curiosity, a test site-cum-monastery, an academy-cum-pleasure dome. The house informs their art as it results from both collective and individual endeavor—something that becomes immediately palpable when one steps into their exhibition at Kunsthalle Zürich. Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian work both individually and in collaboration, but do not form a collective. Their art translates into multiple forms — films, installations, artworks and exhibitions—and often evolves around friends, other artists or people they meet by chance. This includes Iranian artist Niyaz Azadikhah and her sister, a DJ, Nesa Azadikhah, Iranian sculptor Bita Fayyazi, polyglot writer Nazli Ghassemi, American artist Lonnie Holley, gallery manager Minnie McIntyre, Iranian graphic designer and artist Iman Raad, Maaziar Sadr, who works for a telecommunications company in the Emirates, Tamil friends Edward St and Indrani Sirisena. Sometimes these people occupy central roles, sometimes they are marginal, but in either case they bring with them a reality that interrupts the trio’s universe and language, and channels their—and our—attention in unexpected territories. Another important strategy in their practice is the inclusion of various artistic worlds that are as respectfully acknowledged as they are shamelessly appropriated and adapted. -

Protest Visual Arts in Iran from the 1953 Coup to the 1979 Islamic Revolution

International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 2020, 9, 285-299 285 Protest Visual Arts in Iran from the 1953 Coup to the 1979 Islamic Revolution Hoda Zabolinezhad1,* and Parisa Shad Qazvini2 1Phd in Visual Arts from University of Strasbourg, Post-Doc Researcher at Alzahra University of Tehran 2Assisstant Professor at Faculty of Arts, University of Alzahra of Tehran, Iran Abstract: There have been conducted a few numbers of researches with protest-related subjects in visual arts in a span between the two major unrests, the 1953 Coup and the 1979 Islamic Revolution. This study tries to investigate how the works of Iranian visual artists demonstrate their reactions to the 1953 Coup and progresses towards modernization that occurred after the White Revolution of Shāh in 1963. The advent of the protest concept has coincided with the presence of Modern and Contemporary art in Iran when the country was occupied by allies during the Second World War. The 1953 Coup was a significant protest event that motivated some of the artists to react against the monarchy’s intention. Although, poets, authors, journalists, and writers of plays were pioneer to combat dictatorship, the greatest modernist artists of that time, impressed by the events after the 1953 Coup, just used their art as rebellious manifest against the governors. Keywords: Iranian Visual Artists, Pahlavi, Political Freedom, Persian Protest Literature, the Shāh. INTRODUCTION Abrahamian 2018). The Iranian visual arts affected unconstructively by Pahlavi I (1926-1942) contradictory The authors decided to investigate the subject of approaches. By opening of Fine Arts School, which protest artworks because it is almost novel and has became after a while Fine Arts Faculty of the University addressed by the minority of other researchers so far. -

Master's Degree in Economics and Management of Arts and Cultural

Master’s Degree in Economics and Management of Arts and Cultural Activities Final Thesis Contemporary Iranian Art: Emerging Interest in Iranian Art in the International Art Markets and the Reception, Production and Assessment of Iranian Contemporary Art in the International Sphere Supervisor Prof. Cristina Tonghini Graduand Darya Shojai Kaveh 870809 Academic Year 2018 / 2019 Table of Contents Introduction i Acknowledgements vii Chapter One | Historical and political background of Iran from the 20th Century to the 21st Century 1 Introduction 1 1.1 | The Reza Shah Era (1921-2941) 4 1.2 | The Mohammed Reza Shah Era (1941-1979) 12 1.3 | The Islamic Republic of Iran (1979-now) 27 Chapter Two | Tracing the evolution of Iranian art through the 20th and 21st Centuries 35 2.1 | From Kamal ol-Molk to Reza Shah Pahlavi (1880-1940): The beginning of Modern Iranian Art 35 2.2 | Art under Reza Shah Pahlavi (1921-1941) 40 2.3 | Modernisation and Westernisation under Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (1941-1979) 44 2.4 | Art under the Islamic Revolution and the New Millennium (1979-now) 52 Chapter Three | The Art Market for Contemporary Art and the Role of Iran in the Middle East 60 3.1 | Definition of the market for fine arts 60 3.2 | 1980s - 1990s: Emerging countries in the art market and the value of art 60 3.3 | Methodology 66 3.4 | Analysis of the art market: a comparison of Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Tehran Auction 69 3.4.1 | The art market in 2009 and 2010 71 3.4.2 | The art market in 2011 and 2012 77 3.4.3 | The art market in 2013 and 2014 85 3.4.4 | The art market in 2015 and 2016 92 3.4.5 | The art market in 2017 and 2018 98 3.4.6 | The art market in 2019 106 Conclusions 110 Bibliography 116 List of Images 126 Introduction In the last decade, the global fine arts market has grown with unprecedented speed, swiftly recovering from the 2008 financial crisis that enveloped the world’s economy. -

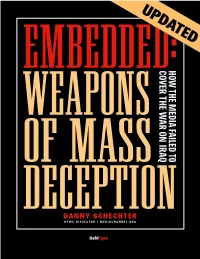

Weapons of Mass Deception

UPDATED. EMBEDDEDCOVER THE WAR ON IRAQ HOW THE TO MEDIA FAILED . WEAPONS OF MASS DECEPTIONDANNY SCHECHTER NEWS DISSECTOR / MEDIACHANNEL.ORG ColdType WHAT THE CRITICS SAID This is the best book to date about how the media covered the second Gulf War or maybe miscovered the second war. Mr. Schecchter on a day to day basis analysed media coverage. He found the most arresting, interesting , controversial, stupid reports and has got them all in this book for an excellent assessment of the media performance of this war. He is very negative about the media coverage and you read this book and you see why he is so negative about it. I recommend it." – Peter Arnett “In this compelling inquiry, Danny Schechter vividly captures two wars: the one observed by embedded journalists and some who chose not to follow that path, and the “carefully planned, tightly controlled and brilliantly executed media war that was fought alongside it,” a war that was scarcely covered or explained, he rightly reminds us. That crucial failure is addressed with great skill and insight in this careful and comprehensive study, which teaches lessons we ignore at our peril.” – Noam Chomsky. “Once again, Danny Schechter, has the goods on the Powers The Be. This time, he’s caught America’s press puppies in delecto, “embed” with the Pentagon. Schechter tells the tawdry tale of the affair between officialdom and the news boys – who, instead of covering the war, covered it up. How was it that in the reporting on the ‘liberation’ of the people of Iraq, we saw the liberatees only from the gunhole of a moving Abrams tank? Schechter explains this later, lubricious twist, in the creation of the frightening new Military-Entertainment Complex.” – Greg Palast, BBC reporter and author, “The Best Democracy Money Can Buy.” "I'm your biggest fan in Iraq. -

Press Release: Recreating the Citadel at Tate Modern

Archaeology of the Final Decade Press Release: Recreating the Citadel at Tate Modern Press Release: Recreating the Citadel at Tate Modern by Archaeology of the Final Decade Archaeology of the Final Decade (AOTFD) is delighted to announce the opening of a room dedicated to Recreating the Citadel: Prostitute (1975-77) at Tate Modern, featuring Kaveh Golestan’s photographic work alongside research materials uncovered by AOTFD. Following the recent acquisition of these materials by the museum, they will be displayed in parallel for the next twelve months within the museum’s permanent collection. The display marks the first time in the museum’s history that a room of the permanent collection has been dedicated to an Iranian artist. Tate’s recent acquisition of twenty vintage prints from Golestan’s Prostitute series comes on the back of recent travelling exhibitions of Recreating the Citadel, curated by AOTFD, at Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam, Musée d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, MAXXI Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo (Rome), and Photo London (Somerset House). Tate’s acquisition follows similar purchases of Golestan’s work by Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Founded by Vali Mahlouji in 2010, Archaeology of the Final Decade is a curatorial and educational platform which identifies, investigates and re-circulates significant cultural and artistic materials that have remained obscure, under-exposed, endangered, or in some instances destroyed. A core aim of AOTFD is the reintegration of these materials into cultural memory, counteracting the damages of censorship and historical erasure.