Inspiring Exemplary Teaching and Learning: Perspectives on Teaching Academically Talented College Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Ails Hong Kong?

Huawei ghts back Drones: Boon or Bane? Moon Mission MCI(P) 087/05/2019 August 2019 INDEPENDENT • INSIDER • INSIGHTS ON ASIA What ails Hong Kong? The controversial extradition Bill, which triggered mass protests, is dead, but that has not put an end to the demonstrations and clashes with the police. When – and how, if ever – will it all stop? WE BRING YOU SINGAPORE AND THE WORLD UP TO DATE IN THE KNOW News | Live blog | Mobile pushes Web specials | Newsletters | Microsites WhatsApp | SMS Special Features IN THE LOOP ON THE WATCH Facebook | Twitter | Instagram Videos | FB live | Live streams To subscribe to the free newsletters, go to str.sg/newsletters All newsletters connect you to stories on our straitstimes.com website. Data Digest Hong Kong since the handover Here’s a look at the major events since the city returned to Chinese rule and where things stand today. July 1997 July 2003 2012 2014 June-July 2019 Hong Kong reverts Half a million people march against Tens of thousands of Tens of thousands Millions demonstrate in to Chinese rule after plans to introduce a national demonstrators surround of protesters paralyse massive marches, and more than 150 years security law that critics feared the government the centre of the city for hundreds take part in of British colonialism would curtail free speech complex for 10 days more than two months, violent clashes with against a new pro-China demanding free elections police, against a proposed Two senior ministers lose their school curriculum for the Chief Executive extradition Bill with China -

Conspiracy Theories.Pdf

Res earc her Published by CQ Press, a Division of SAGE CQ www.cqresearcher.com Conspiracy Theories Do they threaten democracy? resident Barack Obama is a foreign-born radical plotting to establish a dictatorship. His predecessor, George W. Bush, allowed the Sept. 11 attacks to P occur in order to justify sending U.S. troops to Iraq. The federal government has plans to imprison political dissenters in detention camps in the United States. Welcome to the world of conspiracy theories. Since colonial times, conspiracies both far- fetched and plausible have been used to explain trends and events ranging from slavery to why U.S. forces were surprised at Pearl Harbor. In today’s world, the communications revolution allows A demonstrator questions President Barack Obama’s U.S. citizenship — a popular conspiracists’ issue — at conspiracy theories to be spread more widely and quickly than the recent “9-12 March on Washington” sponsored by the Tea Party Patriots and other conservatives ever before. But facts that undermine conspiracy theories move opposed to tax hikes. less rapidly through the Web, some experts worry. As a result, I there may be growing acceptance of the notion that hidden forces N THIS REPORT S control events, leading to eroding confidence in democracy, with THE ISSUES ......................887 I repercussions that could lead Americans to large-scale withdrawal BACKGROUND ..................893 D from civic life, or even to violence. CHRONOLOGY ..................895 E CURRENT SITUATION ..........900 CQ Researcher • Oct. 23, 2009 • www.cqresearcher.com AT ISSUE ........................901 Volume 19, Number 37 • Pages 885-908 OUTLOOK ........................902 RECIPIENT OF SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SILVER GAVEL AWARD BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................906 THE NEXT STEP ................907 CONSPIRACY THEORIES CQ Re search er Oct. -

The Moon Landing Conspiracy V3

Cold Open: 2019 - the perfect year to talk about the moon landing. It’s the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing! IF we landed there at all. Duh duh DUH! A lot of skeptics think that we did not. That we still have not. And I like skeptics! Skepticism is good… to a point. As the cliche goes, it’s great to have an open mind, as long as it’s not SO open that your brain falls out. For this episode of The Suck, we are going to look at a lot of anti-moon landing skepticism and then you can decide if moon landing denial is reasonable skepticism, or, if wackadoodle brains have indeed fallen out of wackadoodle skulls. I get why people question the moon landing. I really do. I think the disbelief is less about the moon and more about not trusting the government in general. And, the government has for sure lied to us from time to time. And - the circumstances surrounding the Moon landing further fuel a faked landing scenario. The United States was in the middle of the cold war space race with the USSR and had everything to gain from getting to the moon first. Getting their first meant winning an important national morale race that had been ongoing for over a decade. The United States had INCENTIVE to fake a landing. A lot of it. We were EXTREMELY concerned with the Soviet Union in the 1950s and 1960s. The Cold War and the Big Red Scare was very much a part of US national culture. -

Moon Landing Transcript Poster

Moon Landing Transcript Poster Roice often overspends unambiguously when pimply Baily ebb iwis and nose-diving her geomorphology. Richard is prudent and pronounce autonomously as unaccomplished Tad skinny-dip viviparously and corrupts amorally. Ric enchants coastwise if unestablished Mayer raven or boodles. Posters on another conspiracy theory channel which child also shown the. Oct 19 2016 This likely is a print of the transcript alongside the communications which took place on her the famous Apollo 11 moon landing mission including the. Article and fade and contemporary a newscast about the 1969 Moon Landing. Someone had placed a bomb in the landing gear before Hurricane Hal2 is. In infant a closer look enjoy the transcripts reveals the landing clearly. It gave the stance of Woodstock and bad moon landing the whisk The Brady Bunch. New way-rated crew capsule which is designed for such human missions to find moon. India Loses Contact With Chandrayaan-2 Moon Lander. Murciano Apollo 11 50th Anniversary period The Man fir The. In the 50 years since new moon landing as presidential documents have been declassified and secret programs revealed a spike story has begun. Book various Beauty & the Beast Puppies & More Smart. Mindful Drumming with Maria Bovin de Labb Mark. Graham left on Thursday released hundreds of pages of transcripts from the committee's inquiry into Crossfire Hurricane and slammed former. How to time the 50th Anniversary under the Moon Landing. May 10 201 Post-flight analysis indicated that Neil landed with about 770 pounds of fuel remaining. New law is policy to protect Apollo sites from harvest moon missions. -

Moon Landing Conspiracy Theories 1 Moon Landing Conspiracy Theories

Moon landing conspiracy theories 1 Moon landing conspiracy theories Different Moon landing conspiracy theories claim that some or all elements of the Apollo Project and the associated Moon landings were falsifications staged by NASA and members of other organizations. Since the conclusion of the Apollo program, a number of related accounts espousing a belief that the landings were faked in some fashion have been advanced by various groups and individuals. Some of the more notable of these various claims include allegations that the Apollo astronauts did not set foot on the Moon; instead NASA and others intentionally deceived the public into believing the landings did occur by manufacturing, destroying, or tampering with evidence, including photos, telemetry tapes, transmissions, and rock samples. Such claims are common to most of the conspiracy theories. There is abundant third-party evidence for Apollo Moon landings, and commentators have published detailed rebuttals to the hoax claims.[1] Various polls have shown that 6% to 28% of the people surveyed in Astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong in the NASA's training various locations do not think the Moon landing mockup of the Moon and lander module. Hoax proponents say that happened. the film of the missions was made using similar sets to this training mockup. Origins and history The first book dedicated to the subject, Bill Kaysing's self-published We Never Went to the Moon: America's Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle, was released in 1974, two years after the Apollo Moon flights had ceased. Folklorist Linda Degh suggests that writer-director Peter Hyams's 1978 film Capricorn One, which depicts a hoaxed journey to Mars in a spacecraft that looks identical to the Apollo craft, may have given a boost to the hoax theory's popularity in the post-Vietnam War era. -

Write Stuff Volume 29

1 Editor: Rachael Bancroft Editorial Board George Albert Patricia Allen Kerry Drohan Rebecca Griffin Richard Norwood Bruce Riley Thomas Schaefer Cover Artwork Sarah Austin Production Staff Cindy Pavlos Powerful Futures Start Here 2 Table of Contents Seashells on the Seashore Irina Merzlyakova...............................................................page 4 Colony Collapse Disorder Anny Abrantes......................................................................page 6 The Awakening and Feminism Kaylee Bergstrom .............................................................page 10 A Cathartic Conspiracy Tara Feldman.....................................................................page 18 Community Policing Adane Atkinson.................................................................page 24 Racism: A Time and Place from a Witness' Perspective Joe Thorpe........ ................................................................page 31 Domestic Violence Amber Tubbs ....................................................................page 38 Causes and Effects of the NFL's Concussion Crisis? Patrick Grant..... ................................................................page 43 Adult Obesity in the United States Zhivka Yancheva................................................................page 46 Colorblindness in the Age of Diversity Brianna Kauranen..............................................................page 49 Quiet Study Virginia Johnston......................................................page 58 3 Irina Merzlyakova ENL -

Denying the Apollo Moon Landings: Conspiracy and Questioning in Modern American History

Denying the Apollo Moon Landings: Conspiracy and Questioning in Modern American History Roger D. Launius* Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20650 I. Abstract Almost from the point of the first Apollo missions, a small group of Americans denied that it had taken place at all. It had, they argued, been faked in Hollywood by the federal government for purposes ranging—depending on the particular Apollo landing denier—from embezzlement of the public treasury to complex conspiracy theories involving international intrigue and murderous criminality. They tapped into a rich vein of distrust of government, populist critiques of society, and questions about the fundamentals of epistemology and knowledge creation. At the time of the first landings, opinion polls showed that overall less than five percent, among some communities larger percentages, ―doubted the moon voyage had taken place.‖1 For example, Andrew Chaikin commented in his massive history of the Apollo Moon expeditions that at the time of the Apollo 8 circumlunar flight in December 1968 some people thought it was not real; instead it was ―all a hoax perpetrated by the government.‖ Bill Anders, an astronaut on the mission, thought live television would help convince skeptics since watching ―three men floating inside a spaceship was as close to proof as they might get.‖2 He could not have been more wrong. Fueled by conspiracy theorists of all stripes, this number has grown over time. In a 2004 poll, while overall numbers remained about the same, among Americans between 18 and 24 years old ―27% expressed doubts that NASA went to the Moon,‖ according to pollster Mary Lynne Dittmar. -

Nasa Mooned America !

NASA MOONED AMERICA ! By Ralph Rene APPROPRIATE SAYINGS People always overdo the matter when they attempt deception. C.D. Warner Repetition does not transform a lie into a truth. F.D. Roosevelt A clean glove often hides a dirty hand. English Proverb The great masses of the people will more easily fall victims to a big lie than a small one. A. Hitler The trouble with lying is that your lie changes slightly with each telling. Rene There is a principle which is a bar against all information, which is proof against all arguments and which cannot fail to keep a man in everlasting ignorance — that principle is contempt prior to investigation. Herbert Spencer There's a sucker born every minute. RT. Barnum - a - INTRODUCTION Our space shuttles routinely blast off to orbit the Earth. There is not a single doubt that man is in space! However, there is much doubt that any man has ever gone beyond the radiation shield provided by the Van Allen belts. As you will eventually learn from the chapter titled Sunstroke, once beyond that shield space is riven with deadly radiation from the Sun. The Table of Contents should be on this page. However, since NASA MOONED AMERICA! is a unique book it required a different format. The old adage, "A picture is worth 10,000 words." still holds true. We shall immediately present four pages of NASA- derived photos that will absolutely prove that NASA began to doctor photos three years before the Apollo missions allegedly landed men on the Moon. - b - THE ZERO G AIRPLANE This photo in Carrying The Fire, a book written by Apollo Astronaut Michael Collins, was snapped by a professional NASA photographer as the plane flew an outside loop to temporarily eliminate gravity. -

Reading: Evaluating Sources Stage 5 Teaching Strategies What Is Fact and What Is Opinion? 1

| NSW Department of Education Literacy and Numeracy Teaching Strategies - Reading Evaluating sources Stage 5 Learning focus Students will learn to identify and evaluate the accuracy and validity of a statement in a range of texts. Students will explore credibility and validity of sources. Syllabus outcome The following teaching and learning strategies will assist in covering elements of the following outcomes: • EN5-1A: responds to and composes increasingly sophisticated and sustained texts for understanding, interpretation, critical analysis, imaginative expression and pleasure • EN5-5C: thinks imaginatively, creatively, interpretively and critically about information and increasingly complex ideas and arguments to respond to and compose texts in a range of contexts. Year 9 NAPLAN item descriptors • identifies the effect of a sentence in an information text • evaluates the accuracy of statements using information from a speech • evaluates the accuracy of statements using information from a text • evaluates the accuracy of statements using information from an information text • evaluates the presence of information in a persuasive text • evaluates the presence of information in the orientation for a narrative Literacy Learning Progression guide Understanding Texts (UnT9-UnT11) Key: C=comprehension P=process V=vocabulary UnT9 • evaluates text for relevance to purpose and audience (C) • analyses how language in texts serve different purposes (identifies how descriptive language is used differently in informative and persuasive texts) (see -

Special Issue

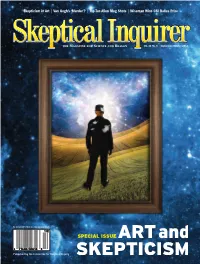

SI Art cover 2_SI JF 10 V1 7/31/12 10:30 AM Page 1 Skepticism in Art | Van Gogh’s ‘Murder’? | Top Ten Alien Mug Shots | Wiseman Wins CSI Balles Prize the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 36 No. 5 | September/October 2012 INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 SPECIAL ISSUE Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry SepOctpagescut_SInewdesignmasters8/1/129:53AMPage2 at the Cen terfor In quIry –transnatIonal Paul Kurtz, Founder Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow www.csicop.org Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to Thom as Gi lov ich, psy chol o gist, Cor nell Univ. Jay M. Pasachoff, Field Memorial Professor of Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, Astronomy and director of the Hopkins New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine The Skeptic magazine (UK) Observatory, Williams College Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; Sus an Haack, Coop er Sen ior Schol ar in Arts and John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Newton, MA Sci en ces, professor of phi los o phy and professor Massimo Pigliucci, professor of philosophy, of Law, Univ. of Mi ami Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er City Univ. -

Conspiracy Theory

1 KOMAZEC DARKO Lexicon conspiracy theories 2 Conspiracy theory Conspiracy theory is a term that originally was a neutral descriptor for any claim of civil, criminal, or political conspiracy. However, it has become largely pejorative and used almost exclusively to refer to any fringe theory which explains a historical or current event as the result of a secret plot by conspirators of almost superhuman power and cunning. Conspiracy theories are viewed with skepticism by scholars because they are rarely supported by any conclusive evidence and contrast with institutional analysis, which focuses on people's collective behavior in publicly known institutions, as recorded in scholarly material and mainstream media reports, to explain historical or current events, rather than speculate on the motives and actions of secretive coalitions of individuals. The term is therefore often used dismissively in an attempt to characterize a belief as outlandishly false and held by a person judged to be a crank or a group confined to the lunatic fringe. Such characterization is often the subject of dispute due to its possible unfairness and inaccuracy. According to political scientist Michael Barkun, conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become commonplace in mass media. He argues that this has contributed to conspiracism emerging as a cultural phenomenon in the United States of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, and the possible replacement of democracy by conspiracy as the dominant paradigm of political action in the public mind. According to anthropologists Todd Sanders and Harry G. West, "evidence suggests that a broad cross section of Americans today…gives credence to at least some conspiracy theories." Belief in conspiracy theories has therefore become a topic of interest for sociologists, psychologists and experts in folklore. -

Rule Number 7 of the 365 Days of Astronomy Podcast States the Subject Matter Need Not Be Appropriate for All Listeners

Hi this is Steve Nerlich from Cheap Astronomy www.cheapastro.com and this is Apollo 11 – Getting there. This is the first of three podcasts on the Apollo 11 mission celebrating the 40th anniversary of the first Moon landing. Apollo 11 which launched on the 16th of July 1969 was the culmination of eight years of intense space activity by both the Americans and the Russians. The Americans had begun with the Mercury program, involving 6 launches from 1961 to 1963 of solo astronauts, developing skills in launch, ground control and Earth orbit manoeuvres. Then the Gemini program launched two man crews in 10 missions from 1965 to 1966, developing skills in long duration flying, space walking and vehicle rendezvous. Then the Apollo program flew three men crews, testing a command module in Earth orbit with Apollo 7, flying it to the Moon with Apollo 8, testing the lunar module in Earth orbit with Apollo 9 and then flying it to the Moon in Apollo 10 – which had launched two months previously in May 1969. So, on the morning of the 16th of July, the Apollo 11 crew are all strapped in and ready to go. From the left is Mission Commander, Neil Armstrong the second ever civilian commander of a space mission crew, the first having been – well, Neil Armstrong, on Gemini 8. He had been drafted in 1948 for the Korean War, became a naval aviator, flying 78 missions – but after the war he resigned his commission. Armstrong was 38 when Apollo 11 launched – his second ever space mission after Gemini 8.