Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Education Professional Experience

CURRICULUM VITAE Name : Nicolas Demertzis Date/Place of Birth : 1958, Athens Citizenship : Greek Home Address : 3 Ikarias street, Agios Stefanos, 14565, Greece Work Address : Faculty of Communication and Media Studies, University of Athens 5, Stadiou st. Athens, 105 62 (tel. +30 210 3689414) National Centre for Social Research 9, Kratinou & Athinas, 105 52, Athens, Greece tel. + 30 210 7491678 email: [email protected], [email protected] Family status: Married, father of one. Url: http://www.media.uoa.gr/people/demertzis Education 1976-1980 B.A. First Class Honour in Political Science: Panteios Graduate School of Political Sciences, Athens 1981-1986 Ph.D. in Sociology : University of Lund, Sweden [Supervisor: R. Eyerman, Examiners: J. Israel, G. Therborn, Thesis Opponent: Z. Bauman] Professional Experience 1989 - 1992 Lecturer in Political Science, Panteion University, Athens 1992 - 1996 Assistant Professor in Political Sociology and Communication, University of Athens 1996 – 2002 Associate Professor in Political Sociology and Communication, University of Athens 2002-present Professor in Political Sociology and Communication, University of Athens 1999-2004 Adjunct Professor in Diplomacy, Foreign Policy and the Media, National School of Public Administration, Athens. 2004-2010 Member of the Interim Committee of the Cyprus University of Technology [CUT], Limassol (www.cut.ac.cy). 2007-2010 Founder and Interim Chairman of the Department of Communication and Internet Studies at CUT. 2007-2010 Interim Dean of the School of Applied Arts and Communication of the Cyprus University of Technology. 2010- present President of the Administrators Board of the Greek State Scholarships Foundation (www.iky.gr). Professional Services 1 1992 - present Member of the Editorial Board of the Greek Political Science Review. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae of Yanis Varoufakis 1. Personal information Place and date of birth: Athens, 24 March 1961 Nationality: Greek and Australian E'mail: [email protected] and [email protected] 2. Educational Background Doctorate: University of Essex, Department of Economics, 1987, PhD in Economics; Title: Optimisation and Strikes; Description: A statistical investigation of competing time series, cross-section, econometric, parametric and game theoretical models of industrial strikes based on USA and UK data. The data sets used were of two forms: macroeconomic (aggregate). and panel data. Supervisor: Professor Monojit Chatterji (currently at Dundee University) Examiners: Professors David Ulph (University of Bristol) and Anthony Shorrocks (University of Essex). Masters: University of Birmingham, Department of Mathematical Statistics, 1982, MSc in Mathematical Statistics Specialisation: Time series, statistical inference, statistical theory, stochastic processes, limited dependent variable estimation, maximum likelihood estimation, non-parametric statistics. Bachelor: University of Essex, School of Mathematical Studies, 1981, BA(Hons) Mathematical Economics High School Moraitis School, Athens, Greece 1 3. Academic positions Primary position January 2013 – Visiting Professor, Lyndon B. Johnson Graduate School of Public Affairs, University of Texas, Austin, USA September 2006 – Professor of Economic Theory, Faculty of Economic Sciences, University of Athens, Athens, Greece September 2000 to September 2006 Associate Professor of Economic -

Educating the Whole Person? the Case of Athens College, 1940-1990

Educating the whole person? The case of Athens College, 1940-1990 Polyanthi Giannakopoulou-Tsigkou Institute of Education, University of London A thesis submitted for the Degree of EdD September 2012 Abstract This thesis is a historical study of the growth and development of Athens College, a primary/secondary educational institution in Greece, during the period 1940-1990. Athens College, a private, non-profit institution, was founded in 1925 as a boys' school aiming to offer education for the whole person. The research explores critically the ways in which historical, political, socio-economic and cultural factors affected the evolution of Athens College during the period 1940-1990 and its impact on students' further studies and careers. This case study seeks to unfold aspects of education in a Greek school, and reach a better understanding of education and factors that affect it and interact with it. A mixed methods approach is used: document analysis, interviews with Athens College alumni and former teachers, analysis of student records providing data related to students' achievements, their family socio-economic 'origins' and their post-Athens College 'destinations'. The study focuses in particular on the learners at the School, and the kinds of learning that took place within this institution over half a century. Athens College, although under the control of a centralised educational system, has resisted the weaknesses of Greek schooling. Seeking to establish educational ideals associated with education of the whole person, excellence, meritocracy and equality of opportunity and embracing progressive curricula and pedagogies, it has been successful in taking its students towards university studies and careers. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Assistant Professor Eleni Zervogianni

CURRICULUM VITAE Assistant Professor Eleni Zervogianni (April 2018) I. PERSONAL INFORMATION & CONTACT DETAILS Birthplace and date Athens, Greece, 7 May 1978 Nationality Greek Affiliation Law School of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Thessaloniki University Campus, 541 24 Thessaloniki, Greece Telephone +30 2310 991175 Emails [email protected] II. STUDIES March 2006 Ph.D. in Civil Law from the University of Athens. Topic: ‘The Restoration of the Status Quo Ante as a Mode of Compensation’ Grade: Excellent (unanimously) Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. M. Stathopoulos. Nov 2001-July ‘Marie Curie Fellowship’ at the Institute of Law and Economics 2002 of the University of Hamburg. October 2001 ‘European Master in Law and Economics’, University of Hamburg, with distinction (average mark 8.41/10), ranked 3rd out of 64 students September 2000 Law Degree from the University of Athens Grade: ‘Very good’ ( 8.29/10) June 1996 High School Diploma from the ‘Moraitis School’ Grade: ‘Excellent’ (19,2 /20) III. HONOURS & SCHOLARSHIPS July 1- Aug. 31, 2009 Scholarship for Post-doctoral research from the Max-Planck- & Feb. 1-15, 2010 Institute for Foreign and Private International Law (Hamburg) June 1 - July 31, 2008 Van Calker Scholarship for research in the Swiss Institute of Comparative Law in Lausanne. Sept. 1- Nov. 30, 2004 Konrad-Zweigert Scholarship for research in the Max-Planck- Institute for Foreign and Private International Law (Hamburg) Oct. 2003 - Feb. 2006 Ph.D. Scholarship from Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation. Oct. 2003 - Feb. 2006 Honorary Ph.D. Scholarship (without financial support) from the 1 Hellenic State Scholarships Foundation. -

Download CHOICE State of the Art Study

State of the art analysis of existing initiatives, best practices and attitudes towards STE(A)M in educational contexts D2.3 State of the Art Study CHOICE Increasing Young People’s Motivation to Choose STEM Careers Through an Innovative Cross-Disciplinary STE(A)M Approach to Education WP2 - State of the art analysis of existing initiatives, best practices and attitudes towards STE(A)M in educational contexts D2.3 State of the Art Study 612849-EPP-1-2019-1-IT-EPPKA3-PI-FORWARD EUROTraining www.eurotraining.gr The European Commission's support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 The EU and National European Contexts .......................................................................................................... 4 Background Information................................................................................................................................ 5 EU policy and civil society position ................................................................................................................ 5 Desk-based research results ........................................................................................................................... -

Victoria Saporta CV

Victoria Saporta E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION October 1993 – October 1997 Ph.D. in Economics Faculty of Economics and Politics, University of Cambridge Title of thesis: Essays in Market Microstructure October 1990 – June 1991 M.Phil in Finance Faculty of Economics and Politics, University of Cambridge Degree Result: Distinction October 1987 – June 1990 B.Sc (Econ) in Mathematical Economics and Econometrics Department of Economics, London School of Economics and Political Science Degree Result: Part I: First, Part II: 2:1 October 1974 – July 1987 Diploma of Higher Education (Apolytirion) Moraitis School, Athens, Greece Grade point average: 19.2/20 (Class Prize) EMPLOYMENT Since June 2014 Bank of England and Prudential Regulatory Authority Director, Financial Policy Responsible for directing the work of two divisions with around 100 full-time equivalent staff with responsibility for developing and delivering prudential policy for both the Board of the Prudential Regulatory Authority (PRA) and the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee – the two statutory bodies with responsibility for microprudential and macroprudential policy respectively in the UK - on capital resources, leverage, liquidity, credit risk, market risk and operational risk for both PRA-authorised banks and insurance firms. Responsible for leading the research efforts of almost 200 staff to support and shape the PRA’s and the Bank’s medium term policy agenda. Member of the PRA’s Executive Committee – the executive body responsible for managing the PRA - and a member of the PRA’s Supervisory, Risk and Policy Committee with executive responsibility for policy decision-making as delegated by PRA Board. July 2009-June 2014 Bank of England, Prudential Policy Division, Financial Stability Head of Division leading a division of 30 full-time equivalent staff within Financial Stability of the Bank of England with responsibility for developing and delivering the post-crisis prudential policy reform agenda of the Bank of England. -

Copy of CV AK Spotify

Antigoni Katsantoni +44 7407274108 | [email protected] | LinkedIn | Portfolio Profile An ambitious and hard-working BSc Management student at the University of Bath, with extensive internship experience in marketing, public relations and media. Also a student radio presenter, with an immense passion for music, who loves working with others, and is reliable, insightful, and exceptionally creative. Education 2018 - 2022 (Expected) UNIVERSITY OF BATH, BSc Management Four-year, thick sandwich degree with an industrial placement in the penultimate year of study. Relevant Modules: Strategic Marketing Communications, Principles of Marketing, Information Systems and Technology, Project Management, Brand Management. Year 1 average: 68%, Year 2 average: 69.2% 2012 - 2018 Moraitis School (Greece), International Baccalaureate Diploma Overall grade 37/45 and Academic Distinction Higher Level subjects: Business Management, Mathematics, English Language & Literature Greek Gymnasium (Middle School) final grade: 19.85/20 Full academic scholarship for all of secondary school Received an Honorary Distinction for my volunteering actions throughout secondary school. Relevant Experience August 2020 - November 2020 PR & INFLUENCE TRAINEE, Ogilvy Greece Working on the accounts of Sakis Rouvas (Greek artist), IKEA and Loumidis Papagalos (Greek coffee brand) My responsibilities included drafting the artist's social media schedule, creating proposals for corporate sponsorships, writing press releases, creating monthly PR reports, monitoring press clippings, measuring KPIs, copywriting influencers' posts and assisting with other administrative tasks. September 2020 - Present INTERNATIONAL MUSIC OFFICER, Student Music Network UK Establishing relationships with international labels, in order to source and distribute music across our network of all student radio stations in the U.K., as well as to further promote and arrange interviews with promising artists. -

Byron College World Scholar's Cup Champions

VOLUME 2, ISSUE 3 MARCH 2019 NEWSLETTER Byron College World Scholar’s Cup Champions Byron College Volume 2, Issue 3 — March 2019 APPLICATIONS NOW OPEN OXFORD GLOBAL SUMMIT FOR YOUNG LEADERS 2019 at Byron College 1-5th July Byron College has taken the initiative to bring to Greece a core group of world class Oxford University post-doctoral research fellows and professors to create a unique educational opportunity for ambitious pupils aged 15-18. The Oxford Global Summit for Young Leaders is aimed at teaching the skills, and providing the mentors and guidance, to challenge and teach design thinking for creative and practical real-world problem solving. OGSYL summer summit will bring together some of the brightest young minds in Greece, and from around the globe, to participate in a challenging life-changing experience. Participants will be assigned to one of four ‘colleges’ intended to represent the college system at the University of Oxford itself. During the summit, students will collaborate and compete on projects and activities that complement seminars and lectures. All course material is original material that has been created for the Summit. Pupils will be inspired and motivated to become the leaders of tomorrow through their interactions with some of the greatest mentors of today. Throughout the summit pupils will be applying their intellect to the most salient issues in our society resulting in the transformation from a group of bright, talented individuals into a team of critical thinking analytical problem-solvers. The Eureka Moment: Can we create it on purpose? The Experience • Group work to identify solutions to a major global challenge that society faces today. -

159 Athena Katsanevaki CHROMATICISM

Athena Katsanevaki Chromaticism – a theoretical construction or… Athena Katsanevaki CHROMATICISM – A THEORETICAL CONSTRUCTION OR A PRACTICAL TRANSFORMATION? Abstract: Chromaticism is a phenomenon which is shared by different musical cultu- res. In the Balkans it is evident both in ecclesiastical and traditional music. In an- tiquity it was attested by ancient Greek writers and was described in theory. It is also apparent in different forms in ancient Greek musical fragments. Nevertheless it is disputed whether it represents a theoretical form (genus) or reflects a musical practice and its formation. Apart from any theoretical analysis of ancient Greek testimony, ethnomusicology can contribute to an explanation by classification and interpretation of various forms in which chromaticism is found in the Balkans. In Northwestern Greece many different forms can offer us various melodic paths that, if followed by vocal or instrumental musical practice, result in special chromatic melodic move- ments. Such movements reveal the genesis of tense chromatic and actually reveal some implications about the differences between the two chromatic shades (tense and soft) in traditional and ecclesiastical music. Keywords: chromatic, hemitonic pentatonic, anhemitonic pentatonic, the Balkans, Nikriz. Introduction In Northwestern Greece a chromatic element is found in traditional melodies. These melodies, using purely pentatonic tunings, present an alteration of a tone on top of the tetrachord. This chromatic element is usually not presented as a clear chromaticism. It is considered to be a practice which colors the melodies. In this system found in Northwestern Greece the chromatic element is attested in many ways as a flexible practice which becomes stabilized and concludes a musical structure. -

Department of Early Childhood Education

DEPARTMENT OF EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF THESSALY CURRICULUM VITAE MARIA TSOUVALA Athens, December 2015 1 CONTENTS 1. PERSONAL INFORMATION 2. EDUCATION.................................................................................................................3 Graduate and Undergraduate Studies Professional Dance Studies Dance Techniques Dance Seminars Other courses related to dance Scholarships Foreign Languages 3. TEACHING EXPERIENCES..........................................................................................5 University of Thessaly Responsibilities in the University of Thessaly In Higher Education (as adjunct Lecturer) Professional Dance Schools Professional Drama Schools Secondary Education Primary Education Other Educational Organizations Dance Seminars 4. ARTISTIC WORK..........................................................................................................12 Contemporary Dance Group Metakinesis Choreographing / Performing Choreographies in Dance Schools and University Departments Choreography / Kinesiology in the Theater Director of Studies / Artistic Director Membership in Artistic Associations 5. RESEARCH-PUBLICATIONS .....................................................................................14 Ph.D. Thesis M.A. Thesis M.Ed. Thesis Articles in Peer Reviewed Journals Articles in Collective Volumes Book Reviews Articles in Art Journals with Editorial Board Dance Reviews Educational Material for the Greek Open University Research Experiences- Projects Presentations in Congresses-Conferences -

2017 Admissions Cycle

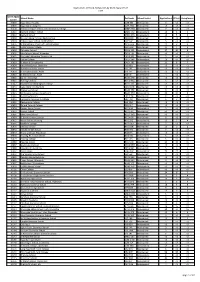

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2017 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 7 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 13 6 5 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 5 5 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 5 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 11 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 17 4 3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 10 8 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 21 8 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 4 <3 <3 10040 Garth Hill College RG42 2AD Maintained <3 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU -

Europass Curriculum Vitae

Europass Curriculum Vitae Personal information First name(s) / Surname(s) Andreas VASSILOPOULOS Address(es) Aristonikou 20-22, 116 36, Mets, Athens - Greece Telephone(s) +30 2102224595 Mobile: +30 6977575320 E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Nationality Greek Date of birth March 03, 1975 Gender Male Desired employment / Occupational Working Experience Dates September 2013 – present Occupation of position held Member of the Managerial team of the Moraitis Primary School (IB) Main activities and responsibilities - Monitor the implementation of the National Legislation in the Primary School - Coordinate the Programme of extra-curricular/sports activities offered in the afternoon (15:30- 16:45) - Coordinate Mathematics teaching in the Primary School (Monitoring the Implementation of the National Curriculum) - Draft the Timetable of the Primary School - Collect, Monitor and Analyze data concerning student achievement Name and address of employer The Moraitis School (www.moraitis-school.com) Papanastasiou & Ag. Dimitriou, 154 52, P. Psyhico Type of business or sector Private School Dates October 2016 – present Occupation of position held Visiting Lecturer (Master in Higher Education Policy: Theory and Praxis) Main activities and responsibilities - Teaching and theses supervision University of Patras, Department of Primary Education (http://mahep.upatras.gr/) Name and address of employer University Type of business or sector Dates September 2017 – Occupation of position held Educator (KEDIVIM – UNIVERSITY OF PATRAS) Main