Balto-Fennic Mythological Names of Baltic Origin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book the Song of the Winns: Vol. 1: the Secret of the Ginger Mice

THE SONG OF THE WINNS: VOL. 1: THE SECRET OF THE GINGER MICE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Frances Watts,Dr. David Francis | 304 pages | 24 Apr 2012 | Running Press | 9780762444106 | English | Philadelphia, United States The Song of the Winns: Vol. 1: The Secret of the Ginger Mice PDF Book Pine-roots were the oldest houses, And the earliest pots were stone ones. Contents: It's no fun to be a lion; the land of the caterpillars; the spider and the fly; the little duck who was very pleased with himself; the big brown bear; the woodchuck; the tiger; the camel; a hot day; the kangaroo; the skunk and the sea gull; from one to ten; the procupine and the badgers; the elephant buys a horse; day; night; the sick sparrow; I see you, little yellow wasps; the fox, the weasel, and the little chicken; the bear went o-ver the mountain; the little black hen; the cottontail and the jack rabbit; the gray squirrel; the elephant; the bear; the greedy kitten and the wise little birds; the goose and the rabbit; the lion; the duck; the hippopotamu; the pig; the funny little mouse. Wherefore do you drive so rashly, And arrive at home so madly? The bride remembers with tears that she is now quitting her dear birthplace for the rest of her life, and says farewell to all While he saw the trees had flourished, And the saplings sprouted bravely, Yet had Jumala's tree, the oak-tree, Not struck down its root and sprouted. On the stone of joy he sat him, On the stone of song he rested, Sang an hour, and sang a second, And again he sang a third time: Thus reversed his words of magic, And dissolved the spell completely. -

”Yksin Syntyi Väinämöinen”

0 ”Yksin syntyi Väinämöinen” Tarkastelussa Kalevalan Maailmansyntyruno Maaret Peltonen Kirjallisuuden kandidaatintutkielma Taiteiden ja kulttuurintutkimuksen laitos Jyväskylän yliopisto Ohjaaja: Anna Helle Opponentti: Hannamari Kilpeläinen Kevät 2016 1 SISÄLTÖ 1 Johdanto ................................................................................................. 2 2 Kalevalan synty ...................................................................................... 3 2.1 Runolaulajat ........................................................................................ 4 2.2 Runolaulajan maailma ......................................................................... 6 3 Myytit ja Kalevala .................................................................................. 6 4 Aineiston kuvaus ja analyysi ................................................................. 9 4.1 Aineiston kuvaus ................................................................................. 9 4.2 Aineiston analyysi ............................................................................... 11 5 Johtopäätökset ..................................................................................... 16 6 Päätäntö ................................................................................................ 17 Lähteet 2 1 Johdanto Tutkin kirjallisuuden kandidaatin tutkielmassani Kalevalan ja Raamatun välistä suhdetta ja yhteyttä. Etenen Kalevalan tutkimisessa myyttien kautta Raamattuun. Mielenkiintoni Kalevalan ja Raamatun väliseen yhteyteen on -

Visits to Tuonela Ne of the Many Mythologies Which Have Had an In

ne of the many mythologies which have had an in fluence on Tolkien's work was the Kalevala, the 22000- line poem recounting the adventures of a group of Fin nish heroes. It has many characteristics peculiar to itself and is quite different from, for example, Greek or Germanic mythology. It would take too long to dis cuss this difference, but the prominent role of women (particularly mothers) throughout the book may be no ted, as well as the fact that the heroes and the style are 'low-brow', as Tolkien described them, as opposed to the 'high-brow' heroes common in other mytholog- les visits to Tuonela (Hades) are fairly frequent; and magic and shape-change- ing play a large part in the epic. Another notable feature which the Kaleva la shares with QS is that it is a collection of separate, but interrelated, tales of heroes, with the central theme of war against Pohjola, the dreary North, running through the whole epic, and individual themes in the separate tales. However, it must be appreciated that QS, despite the many influences clearly traceable behind it, is, as Carpenter reminds us, essentially origin al; influences are subtle, and often similar incidents may occur in both books, but be employed in different circumstances, or be used in QS simply as a ba sis for a tale which Tolkien would elaborate on and change. Ibis is notice able even in the tale of Turin (based on the tale of Kullervo), in which the Finnish influence is strongest. I will give a brief synopsis of the Kullervo tale, to show that although Tolkien used the story, he varied it, added to it, changed its style (which cannot really be appreciated without reading the or iginal ), and moulded it to his own use. -

Laura Stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion

laura stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion Studia Fennica Folkloristica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Laura Stark Peasants, Pilgrims, and Sacred Promises Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion Finnish Literature Society • Helsinki 3 Studia Fennica Folkloristica 11 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via Helsinki University Library. © 2002 Laura Stark and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International. A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-366-9 (Print) ISBN 978-951-746-578-6 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-766-9 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 1235-1946 (Studia Fennica Folkloristica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sff.11 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. -

Helgenforteljingane Si Rolle I Tidleg Jødedom, Kristendom Og Islam

Det velges mellom: RELV202/302 The Religions and Mythologies of the Baltic Finns og RELV202/302: Hagiografiar - Helgenforteljingane si rolle i tidleg jødedom, kristendom og islam RELV202/302 The Religions and Mythologies of the Baltic Finns Course literature Books (can be borrowed at the University Library or bought by the student) The Kalevala (Oxford World’s Classics). Translated by Keith Bosley. Oxford 2009: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-53886-7. Or a translation of the Kalevala into your own language; some examples: Kalevala [Danish]. [Transl. by] Ferdinand Ohrt. Copenhagen 1985 and later: Reitzel. Le Kalevala [French]. [Transl. by] Gabriel Rebourcet. Paris 2010: Gallimard, coll. Quarto. Kalevala [German]. [Transl. by] Lore Fromm & Hans Fromm. Wiesbaden 2005: Marix Verlag. Kalevala [Norwegian]. [Transl. by] Albert Lange Fliflet. Oslo 1999: Aschehoug. El Kalevala [Spanish]. [Transl. by] juan Bautista Bergua. Madrid 1999: Ediciones Ibéricas. Kalevala [Swedish]. [Transl. by] Lars Huldén & Mats Huldén. Stockholm 2018: Atlantis. (For a full list of translations, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Kalevala_translations) NB! Only songs 1–15, 39–49. Pentikäinen, Juha. 1999. Kalevala Mythology. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33661-9 (pbk). 296 pp. Siikala, Anna-Leena. 2002. Mythic Images and Shamanism: A Perspective on Kalevala Poetry. Helsinki: Suomalainen tiedeakademia / Finnish Academy of Science and Letters. ISBN 951-41-0902-3 (pbk). 423 pp. Book chapters – can be ordered from litteraturkiosken.uib Finnish Folk Poetry-Epic: An Anthology in Finnish and English (Publications of the Finnish Literature Society 329). Helsinki 1977: Finnish Literature Society. ISBN 951-717-087-4. Only the following pages: 83–92 (Creation), 98 (Smith), 102–109 (Singing match), 183–190 (The spell), 191–195 (Tuonela), 195–199 (Sun and moon), 212–220 (Lemminkäinen), 281–282 (Lähtö), 315–320 (St. -

Finnish Studies

Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 23 Number 1 November 2019 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-7328298-1-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458, Box 2146, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hilary-Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Tim Frandy, Assistant Professor, Western Kentucky University Daniel Grimley, Professor, Oxford University Titus Hjelm, Associate Professor, University of Helsinki Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Johanna Laakso, Professor, University of Vienna Jason Lavery, Professor, Oklahoma State University James P. Leary, Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, University of Helsinki Jussi Nuorteva, Director General, The National Archives of Finland Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury Beth L. -

And Estonian Kalev

Scandinavian Kalf and Estonian Kalev HILDEGARD MUST OLD ICELANDIC SAGAStell us about several prominent :men who bore the name Kalfr, Kalfr, etc.1 The Old Swedish form was written as Kalf or Kalv2 and was a fairly common name in Viking-age Scandinavia. An older form of the same name is probably kaulfR which is found on a runic stone (the Skarby stone). On the basis of this form it is believed that the name developed from an earlier *Kaoulfr which goes back to Proto-Norse *KapwulfaR. It is then a compound as are most of old Scandinavian anthroponyms. The second ele- ment of it is the native word for "wolf," ON"ulfr, OSw. ulv (cf. OE, OS wulf, OHG wolf, Goth. wulfs, from PGmc. *wulfaz). The first component, however, is most likely a name element borrowed from Celtic, cf. Old Irish cath "battle, fight." It is contained in the Old Irish name Cathal which occurred in Iceland also, viz. as Kaoall. The native Germ.anic equivalents of OIr. cath, which go back to PGmc. hapu-, also occurred in personal names (e.g., as a mono- thematic Old Norse divine name Hr;or), and the runic HapuwulfR, ON Hr;lfr and Halfr, OE Heaouwulf, OHG Haduwolf, Hadulf are exact Germanic correspondences of the hybrid Kalfr, Kalfr < *Kaoulfr. However, counterparts of the compound containing the Old Irish stem existed also in other Germanic languages: Oeadwulf in Old English, and Kathwulf in Old High German. 3 1 For the variants see E. H. Lind, Nor8k-i8liind8ka dopnamn och fingerade namn fran medeltiden (Uppsala and Leipzig, 1905-15), e. -

The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot's Kalevala

Oral Tradition, 8/2 (1993): 247-288 From Maria to Marjatta: The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala1 Thomas DuBois The question of Elias Lönnrot’s role in shaping the texts that became his Kalevala has stirred such frequent and vehement debate in international folkloristic circles that even persons with only a passing interest in the subject of Finnish folklore have been drawn to the question. Perhaps the notion of academic fraud in particular intrigues those of us engaged in the profession of scholarship.2 And although anyone who studies Lönnrot’s life and endeavors will discover a man of utmost integrity, it remains difficult to reconcile the extensiveness of Lönnrot’s textual emendations with his stated desire to recover and present the ancient epic traditions of the Finnish people. In part, the enormity of Lönnrot’s project contributes to the failure of scholars writing for an international audience to pursue any analysis beyond broad generalizations about the author’s methods of compilation, 1 Research for this study was funded in part by a grant from the Graduate School Research Fund of the University of Washington, Seattle. 2 Comparetti (1898) made it clear in this early study of Finnish folk poetry that the Kalevala bore only partial resemblance to its source poems, a fact that had become widely acknowledged within Finnish folkoristic circles by that time. The nationalist interests of Lönnrot were examined by a number of international scholars during the following century, although Lönnrot’s fairly conservative views on Finnish nationalism became equated at times with the more strident tone of the turn of the century, when the Kalevala was made an inspiration and catalyst for political change (Mead 1962; Wilson 1976; Cocchiara 1981:268-70; Turunen 1982). -

Saami Religion

Edited by Tore Ahlbäck Saami Religion SCRIPTA INSTITUTI DONNERIANI ABOENSIS XII SAAMI RELIGION Based on Papers read at the Symposium on Saami Religion held at Åbo, Finland, on the 16th-18th of August 1984 Edited by TORE AHLBÄCK Distributed by ALMQVIST & WIKSELL INTERNATIONAL, STOCKHOLM/SWEDEN Saami Religion Saami Religion BASED ON PAPERS READ AT THE SYMPOSIUM ON SAAMI RELIGION HELD AT ÅBO, FINLAND, ON THE 16TH-18TH OF AUGUST 1984 Edited by TORE AHLBÄCK PUBLISHED BY THE DONNER INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH IN ÅBO/FINLANDRELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL HISTORY DISTRIBUTED BY ALMQVIST & WIKSELL INTERNATIONAL STOCKHOLM/SWEDEN ISBN 91-22-00863-2 Printed in Sweden by Almqvist & Wiksell Tryckeri, Uppsala 1987 Reproduction from a painting by Carl Gunne, 1968 To Professor Carl-Martin Edsman on the occasion of his seventififth birthday 26 July 1986 Contents Editorial note 9 CARL-MARTIN EDSMAN Opening Address at the Symposium on Saami religion arranged by the Donner Institute 16-18 August 1984 13 ROLF KJELLSTRÖM On the continuity of old Saami religion 24 PHEBE FJELLSTRÖM Cultural- and traditional-ecological perspectives in Saami religion 34 OLAVI KORHONEN Einige Termini der lappischen Mythologie im sprachgeographischen Licht 46 INGER ZACHRISSON Sjiele sacrifices, Odin treasures and Saami graves? 61 OLOF PETTERSSON t Old Nordic and Christian elements in Saami ideas about the realm of the dead 69 SIV NORLANDER-UNSGAARD On time-reckoning in old Saami culture 81 ØRNULV VORREN Sacrificial sites, types and function 94 ÅKE HULTKRANTZ On beliefs in non-shamanic guardian spirits among the Saamis 110 JUHA Y. PENTIKÄINEN The Saami shamanic drum in Rome 124 BO LÖNNQVIST Schamanentrachten in Sibirien 150 BO LUNDMARK Rijkuo-Maja and Silbo-Gåmmoe - towards the question of female shamanism in the Saami area 158 CARL F. -

The Role of the Kalevala in Finnish Culture and Politics URPO VENTO Finnish Literature Society, Finland

Nordic Journal of African Studies 1(2): 82–93 (1992) The Role of the Kalevala in Finnish Culture and Politics URPO VENTO Finnish Literature Society, Finland The question has frequently been asked: would Finland exist as a nation state without Lönnrot's Kalevala? There is no need to answer this, but perhaps we may assume that sooner or later someone would have written the books which would have formed the necessary building material for the national identity of the Finns. During the mid 1980s, when the 150th anniversary of the Kalevala was being celebrated in Finland, several international seminars were held and thousands of pages of research and articles were published. At that time some studies appeared in which the birth of the nation state was examined from a pan-European perspective. SMALL NATION STATES "The nation state - an independent political unit whose people share a common language and believe they have a common cultural heritage - is essentially a nineteenth-century invention, based on eighteenth-century philosophy, and which became a reality for the most part in either the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. The circumstances in which this process took place were for the most part marked by the decline of great empires whose centralised sources of power and antiquated methods of administrations prevented an effective response to economic and social change, and better education, with all the aspirations for freedom of thought and political action that accompany such changes." Thus said Professor Michael Branch (University of London) at a conference on the literatures of the Uralic peoples held in Finland in the summer of 1991. -

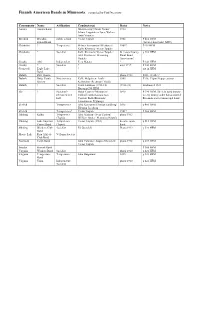

Finnish American Bands in Minnesota, Compiled by Paul Niemisto

Finnish American Bands in Minnesota, compiled by Paul Niemisto Community Name Affiliation Conductor(s) Dates Notes Aurora Aurora Band Miettinen(sp?)/Matti Niemi/ 1910 Jalmar Laupiainen/ Isaac Walma/ Antti Viitanen. Biwabik Biwabik public school Victor Taipale 1902 P 482 HFM School Band (1st in school band MN?) Chisholm ? Temperence Helmer hermanson/ Miettunen/ 1904? P494 HFM Kalle Kleimola/ Victor Taipale Chisholm ? Socialist Kalle Kleimola/ Victor Taipale/ St Louis County p 498 HFM Alex Koivunen/ Hemming Rural Band Hautala Association? Crosby Ahti Independent Eero Matara ? P 141 HFM Crosby ? Socialist ? after 1917 P 141 HFM Cromwell Eagle Lake ? not in HFM Band Duluth SSO Osasto photo 1913 P243, cl+trb+7 Duluth Nuija Youth Nuorisoseura Kalle Holpainen/ Louhi/ 1905 P246, Viipuri/Lappeenranta Society Kellosalmi/ Beckman/ Yrjölä Duluth ? Socialist Frank Lindroos (1913-18) (1913-18) Lindroos d 1923 Bio on p 298 HFM Ely ? Socialist?- Oskar Castren/ Miettunen/ 1890 P 390 HFM, The Ely band history rehearsed in S Farihoff/ Erkki Laitala/Jack is very murky/ other bands started/ hall Castren/ Kalle Kleimola/ Kleemols started municipal band Liimatainen/ Pyylampi Eveleth Termperence Alex Koivunen/ Herman Lindberg/ 1895 p 466 HFM Filemon Jacobson Eveleth Termperence? Victor Taipale 1901? P 466 HFM Hibbing Kaiku Temperence Alex Mattson/ Oscar Castren/ photo 1913 (Tapio) William Ahola/ Hemming Hautala Hibbing Lake Superior Temperence Victor Taipale (1901) became town p 512 HFM Cornet Band (Tapio) band Hibbing Workers Club Socialist Ed Grondahl Photo 1912 p 521 HFM Band Moose Lake Raju Athletic Vellamo Society Club Band Naswauk Town Band John Colander/ August Miettinen/ photo 1912 p 607 HFM Victor Taipale Soudan Finnish Band P 366 HFM Virginia Workers Band Socialist photo 1910 p 421 HFM Virginia Temperance Temperance John Haapasaari 1895 p 422 HFM Band Virginia Yrinä Independent/ photo 1910 p 422 HFM Socialist . -

Web Fact Sheets

Jaakko Mäntyjärvi ================= Kosijat (2001) The suitors 0. Intro 1. Aurinko (The Sun) 2. Kuu (The Moon) 3. Pohjantähti (The North Star) Ensemble :: Kokoonpano 4xS 4xA 4xT 4xB (16) Duration :: Kesto 20 min Publisher :: Kustantaja Sulasol S775 Text :: Teksti Kanteletar FI Commissioned by :: Tilaaja The Esoterics, Seattle (Washington), USA Premiere :: Kantaesitys The Esoterics / Eric Banks Seattle xi.2001 About Finnish folk poetry Suomettaren kosijat on siitä mielenkiintoinen teksti, että se on Serious interest in ancient Finnish folk kutakuinkin ainoa suomalainen kansanruno, poetry emerged in the early 19th century jossa aurinko ja kuu käsitellään with the development of the National erillisinä. Yleensä ne esiintyvät aina Romantic movement in Finland. This is not parina (”ei päivä paista eikä kuu to say that the oral tradition was kumota”). Niinpä tämä teksti sopi unfamiliar to scholars before that; for erinomaisesti tilaukseen, jonka Eric example, Henrik Gabriel Porthan (1739- Banks esitti minulle Corkin 1804) brought Finnish history-writing, kansainvälisellä kuorofestivaalilla study of mythology and folk poetry and toukokuussa 2000. Hänen kuoronsa (The other humanistic sciences to an Esoterics) tulevan vuoden konserttisarjan international level and sparked public teemana oli aurinko, kuu ja tähdet. Se, interest in what later came to be known miksi hän sitten halusi kuorolleen 20- as Kalevala poetry and Finnish mythology. minuuttisen teoksen suomeksi, on edelleen minulle arvoitus, mutta erittäin hyvin he Finland had become an autonomous Grand tehtävästä selviytyivät. Duchy in the Russian Empire in 1809, having been part of the Kingdom of Sweden Suomalaisille esittäjille ja kuulijoille before that, and this contributed in no on päivänselvää, missä määrin tämä teos small way to the National Romantic nojaa kalevalaiseen perinteeseen.