The Persistence of Torture: Explaining Coercive Interrogation in America's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law Release Date: April 23, 2018

Release Date: April 23, 2018 CERL Report on The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law Release Date: April 23, 2018 CERL Report on The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law I. Introduction On January 25, 2017, President Trump repeated his belief that torture works1 and reaffirmed his commitment to restore the use of harsh interrogation of detainees in American custody.2 That same day, CBS News released a draft Trump administration executive order that would order the Intelligence Community (IC) and Department of Defense (DoD) to review the legality of torture and potentially revise the Army Field Manual to allow harsh interrogations.3 On March 13, 2018, the President nominated Mike Pompeo to replace Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State, and Gina Haspel to replace Mr. Pompeo as Director of the CIA. Mr. Pompeo has made public statements in support of torture, most notably in response to the Senate Intelligence Committee’s 2014 report on the CIA’s use of torture on post-9/11 detainees,4 though his position appears to have altered somewhat by the time of his confirmation hearing for Director of the CIA, and Ms. Haspel’s history at black site Cat’s Eye in Thailand is controversial, particularly regarding her oversight of the torture of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri5 as well as her role in the destruction of video tapes documenting the CIA’s use of enhanced interrogation techniques.6 In light of these actions, President Trump appears to be signaling his support for legalizing the Bush-era techniques applied to detainees arrested and interrogated during the war on terror. -

Freedom Or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 Spring 2005 Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Hannibal Travis, Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq, 3 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 1 (2005). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of Law Volume 3 (Spring 2005) Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights FREEDOM OR THEOCRACY?: CONSTITUTIONALISM IN AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ By Hannibal Travis* “Afghans are victims of the games superpowers once played: their war was once our war, and collectively we bear responsibility.”1 “In the approved version of the [Afghan] constitution, Article 3 was amended to read, ‘In Afghanistan, no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.’ … This very significant clause basically gives the official and nonofficial religious leaders in Afghanistan sway over every action that they might deem contrary to their beliefs, which by extension and within the Afghan cultural context, could be regarded as -

Global War on Terror

SADAT MACRO 9/14/2009 8:38:06 PM A PRESUMPTION OF GUILT: THE UNLAWFUL ENEMY COMBATANT AND THE U.S. WAR ON TERROR * LEILA NADYA SADAT I. INTRODUCTION Since the advent of the so-called “Global War on Terror,” the United States of America has responded to the crimes carried out on American soil that day by using or threatening to use military force against Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Pakistan. The resulting projection of American military power resulted in the overthrow of two governments – the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, the fate of which remains uncertain, and Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq – and “war talk” ebbs and flows with respect to the other countries on the U.S. government’s “most wanted” list. As I have written elsewhere, the Bush administration employed a legal framework to conduct these military operations that was highly dubious – and hypocritical – arguing, on the one hand, that the United States was on a war footing with terrorists but that, on the other hand, because terrorists are so-called “unlawful enemy combatants,” they were not entitled to the protections of the laws of war as regards their detention and treatment.1 The creation of this euphemistic and novel term – the “unlawful enemy combatant” – has bewitched the media and even distinguished justices of the United States Supreme Court. It has been employed to suggest that the prisoners captured in this “war” are not entitled to “normal” legal protections, but should instead be subjected to a régime d’exception – an extraordinary regime—created de novo by the Executive branch (until it was blessed by Congress in the Military * Henry H. -

Open Hearing: Nomination of Gina Haspel to Be the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

S. HRG. 115–302 OPEN HEARING: NOMINATION OF GINA HASPEL TO BE THE DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY HEARING BEFORE THE SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION WEDNESDAY, MAY 9, 2018 Printed for the use of the Select Committee on Intelligence ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 30–119 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 VerDate Sep 11 2014 14:25 Aug 20, 2018 Jkt 030925 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\30119.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE [Established by S. Res. 400, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.] RICHARD BURR, North Carolina, Chairman MARK R. WARNER, Virginia, Vice Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARCO RUBIO, Florida RON WYDEN, Oregon SUSAN COLLINS, Maine MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico ROY BLUNT, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma JOE MANCHIN III, West Virginia TOM COTTON, Arkansas KAMALA HARRIS, California JOHN CORNYN, Texas MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky, Ex Officio CHUCK SCHUMER, New York, Ex Officio JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Ex Officio JACK REED, Rhode Island, Ex Officio CHRIS JOYNER, Staff Director MICHAEL CASEY, Minority Staff Director KELSEY STROUD BAILEY, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 14:25 Aug 20, 2018 Jkt 030925 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\30119.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER CONTENTS MAY 9, 2018 OPENING STATEMENTS Burr, Hon. Richard, Chairman, a U.S. Senator from North Carolina ................ 1 Warner, Mark R., Vice Chairman, a U.S. Senator from Virginia ........................ 3 WITNESSES Chambliss, Saxby, former U.S. -

Table of Contents

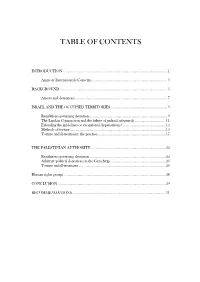

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 Amnesty International's Concerns ..................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 Arrests and detentions ........................................................................................................ 7 ISRAEL AND THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES ................................................................ 9 Regulations governing detention ........................................................................................ 9 The Landau Commission and the failure of judicial safeguards ................................. 11 Extending the guidelines or exceptional dispensations? ................................................ 14 Methods of torture ............................................................................................................ 15 Torture and ill-treatment: the practice ............................................................................. 17 THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 22 Regulations governing detention ...................................................................................... 22 Arbitrary political detentions in the Gaza Strip .............................................................. -

Introduction

1 Introduction Intelligence collection is one of the earliest recorded organized human activ- ities, along with war. The earliest writing about intelligence collection dates from the seventh and sixth centuries BCE: Caleb the spy in the Book of Numbers and The Art of War by Sun Tzu. It is striking that two cultures, ancient Hebrew and Chinese, geographically remote from one another and undoubtedly unknown to one another, should both discuss the importance of intelligence collection at roughly the same time in an early part of human history. But the precept is elementary at its core—information confers power. Whoever is best at gathering (and exploiting) relevant information tends to win. In the twenty-fi rst century, the U.S. Intelligencedistribute Community (IC) is premier in its capabilities for doing both. Collection in the IC generally refers to fi ve ordisciplines (or sources): Open Source Intelligence (OSINT), Human Intelligence (HUMINT), Signals Intel- ligence (SIGINT), Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT), and Measurement and Signature Intelligence (MASINT). A great deal of mystery and myth surrounds the subject of those sources and the capabilities and uses implied. And many popular perceptions are far afi eld from reality. That is why we have written this book. Our intentionpost, is to give readers an approachable but detailed picture of U.S. intelligence collection capabilities. To that end, each chapter follows a similar construct. We discuss the unique origin and history of the INT, or intelligence collection discipline, which is important to under- stand in terms of both its development and how it is used today. We discuss the types of intelligencecopy, issues that each INT is best suited for and those for which it is of little help. -

Six Questions for Jane Mayer, Author of the Dark Side

Six Questions for Jane Mayer, Author of The Dark Side By Scott Horton, HARPER’S, July, 2008 In a series of gripping articles, Jane Mayer has chronicled the Bush Administration’s grim and furtive dealings with torture and has exposed both the individuals within the administration who “made it happen” (a group that starts with Vice President Cheney and his chief of staff, David Addington), the team of psychologists who put together the palette of techniques, and the Fox television program “24,” which was developed to help sell it to the American public. In a new book, The Dark Side, Mayer puts together the major conclusions from her articles and fills in a number of important gaps. Most significantly, we learn the details on the torture techniques and the drama behind the fierce and lingering struggle within the administration over torture, and we learn that many within the administration recognized the potential criminal accountability they faced over these torture tactics and moved frantically to protect themselves from possible future prosecution. I put six questions to Jane Mayer on the subject of her book, The Dark Side. 1. Reports have circulated for some time that the Red Cross examination of the CIA’s highly coercive interrogation regime—what President Bush likes to call “The Program”—concluded that it was “tantamount to torture.” But you write that the Red Cross categorically described the program as “torture.” The Red Cross is notoriously tight-lipped about its reports, and you do not cite your source or even note that you examined the report. Do you believe that the threat of criminal prosecution drove the Bush Administration’s crafting of the Military Commissions Act? Whether anyone involved in the Bush Administration’s interrogation and detention program will be prosecuted is as much a political question as a legal one. -

The Abu Ghraib Convictions: a Miscarriage of Justice

Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal Volume 32 Article 4 9-1-2013 The Abu Ghraib Convictions: A Miscarriage of Justice Robert Bejesky Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Robert Bejesky, The Abu Ghraib Convictions: A Miscarriage of Justice, 32 Buff. Envtl. L.J. 103 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/bpilj/vol32/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Public Interest Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ABU GHRAIB CONVICTIONS: A MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE ROBERT BEJESKYt I. INTRODUCTION ..................... ..... 104 II. IRAQI DETENTIONS ...............................107 A. Dragnet Detentions During the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq.........................107 B. Legal Authority to Detain .............. ..... 111 C. The Abuse at Abu Ghraib .................... 116 D. Chain of Command at Abu Ghraib ..... ........ 119 III. BASIS FOR CRIMINAL CULPABILITY ..... ..... 138 A. Chain of Command ....................... 138 B. Systemic Influences ....................... 140 C. Reduced Rights of Military Personnel and Obedience to Authority ................ ..... 143 D. Interrogator Directives ................ .... -

Confidentiality Complications

Confidentiality Complications: How new rules, technologies and corporate practices affect the reporter’s privilege and further demonstrate the need for a federal shield law The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press June 2007 Lucy A. Dalglish, Esq. Gregg P. Leslie, Esq. Elizabeth J. Soja, Esq. 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 Arlington, Virginia 22209 (703) 807-2100 Executive Summary The corporate structure of the news media has created new obstacles, both financial and practical, for journalists who must keep promises of confidentiality. Information that once existed only in a reporter’s notebook can now be accessed by companies that have obligations not only to their reporters, but to their shareholders, their other employees, and the public. Additionally, in the wake of an unprecedented settlement in the Wen Ho Lee Privacy Act case, parties can target news media corporations not just for their access to a reporter’s information, but also for their deep pockets. The potential for conflicts of interest is staggering, but the primary concerns of The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press are that: • because of the 21st-century newsroom’s reliance on technology, corporations now have access to notes, correspondence and work-product information that before only existed in a reporter’s notebook; • the new federal “e-discovery” court rules allow litigants to discover vastly more information than a printed page – or even a saved e-mail – would provide during litigation; • while reporters generally only have responsibilities to themselves, -

Dueling Absurdities

Dueling Delusions: Terrorism and Counterterrorism in the United States Since 9/11 John Mueller Ohio State University and Cato Institute Mark G. Stewart University of Newcastle November 9, 2011 Prepared for presentation at the Program on International Security Policy University of Chicago, November 15, 2011 John Mueller Senior Research Scientist, Mershon Center for International Security Studies Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43201, United States Cato Senior Fellow, Cato Institute 1000 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20001, United States polisci.osu.edu/faculty/jmueller +1 614 247-6007 [email protected] Mark G. Stewart Australian Research Council Professorial Fellow Professor and Director, Centre for Infrastructure Performance and Reliability The University of Newcastle New South Wales, 2308, Australia www.newcastle.edu.au/research-centre/cipar/staff/mark-stewart.html +61 2 49216027 [email protected] ABSTRACT: A preliminary, if rather lengthy, set of ruminations on our ten years, and counting, of absurdity and delusion on the terrorism issue. It seems increasingly likely that the reaction to the terrorism attacks of September 11, 2001, was massively disproportionate to the real threat al- Qaeda has ever actually presented either as an international menace or as an inspiration or model to homegrown amateurs. But the terrorism/counterterrorism saga trudges determinedly, doggedly, and anti-climactically onward: people profess fear of another attack, funds continue to be expended irresponsibly, and killing continues, all in the name of the fabled tragedy of 9/11. A warning: the paper includes reference to the Wizard of Oz and to The Emperor’s New Clothes and may not be suitable for all audiences. -

![Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0418/download-music-for-free-in-work-even-though-it-gains-access-to-it-680418.webp)

Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It

Vol. 54 No. 3 NIEMAN REPORTS Fall 2000 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 4 Narrative Journalism 5 Narrative Journalism Comes of Age BY MARK KRAMER 9 Exploring Relationships Across Racial Lines BY GERALD BOYD 11 The False Dichotomy and Narrative Journalism BY ROY PETER CLARK 13 The Verdict Is in the 112th Paragraph BY THOMAS FRENCH 16 ‘Just Write What Happened.’ BY WILLIAM F. WOO 18 The State of Narrative Nonfiction Writing ROBERT VARE 20 Talking About Narrative Journalism A PANEL OF JOURNALISTS 23 ‘Narrative Writing Looked Easy.’ BY RICHARD READ 25 Narrative Journalism Goes Multimedia BY MARK BOWDEN 29 Weaving Storytelling Into Breaking News BY RICK BRAGG 31 The Perils of Lunch With Sharon Stone BY ANTHONY DECURTIS 33 Lulling Viewers Into a State of Complicity BY TED KOPPEL 34 Sticky Storytelling BY ROBERT KRULWICH 35 Has the Camera’s Eye Replaced the Writer’s Descriptive Hand? MICHAEL KELLY 37 Narrative Storytelling in a Drive-By Medium BY CAROLYN MUNGO 39 Combining Narrative With Analysis BY LAURA SESSIONS STEPP 42 Literary Nonfiction Constructs a Narrative Foundation BY MADELEINE BLAIS 43 Me and the System: The Personal Essay and Health Policy BY FITZHUGH MULLAN 45 Photojournalism 46 Photographs BY JAMES NACHTWEY 48 The Unbearable Weight of Witness BY MICHELE MCDONALD 49 Photographers Can’t Hide Behind Their Cameras BY STEVE NORTHUP 51 Do Images of War Need Justification? BY PHILIP CAPUTO Cover photo: A Muslim man begs for his life as he is taken prisoner by Arkan’s Tigers during the first battle for Bosnia in March 1992. -

Law Enforcement Intelligence: a Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies

David L. Carter, Ph.D. School of Criminal Justice Michigan State University Law Enforcement Intelligence: A Guide for State, Local, and Tribal Law Enforcement Agencies November 2004 David L. Carter, Ph.D. This project was supported by Cooperative Agreement #2003-CK-WX-0455 by the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. Points of view or opinions contained in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or Michigan State University. Preface The world of law enforcement intelligence has changed dramatically since September 11, 2001. State, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies have been tasked with a variety of new responsibilities; intelligence is just one. In addition, the intelligence discipline has evolved significantly in recent years. As these various trends have merged, increasing numbers of American law enforcement agencies have begun to explore, and sometimes embrace, the intelligence function. This guide is intended to help them in this process. The guide is directed primarily toward state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies of all sizes that need to develop or reinvigorate their intelligence function. Rather than being a manual to teach a person how to be an intelligence analyst, it is directed toward that manager, supervisor, or officer who is assigned to create an intelligence function. It is intended to provide ideas, definitions, concepts, policies, and resources. It is a primer- a place to start on a new managerial journey. Every effort was made to incorporate the state of the art in law enforcement intelligence: Intelligence-Led Policing, the National Criminal Intelligence Sharing Plan, the FBI Intelligence Program, the array of new intelligence activities occurring in the Department of Homeland Security, community policing, and various other significant developments in the reengineered arena of intelligence.