Sharon Francis Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin of the Maryland Ornithological Society, Inc. SEPTEMBER

ISSN 047-9725 September–December 2003 MARYLAND BIRDLIFE Bulletin of the Maryland Ornithological Society, Inc. SEPTEMBER–DECEMBER 2003 VOLUME 59 NUMBERS 3–4 MARYLAND ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY, INC. Cylburn Mansion, 495 Greenspring Ave., Baltimore, Maryland 2209 STATE OFFICERS FOR JUNE 2003 TO JUNE 2004 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL President: Paul Zucker, 283 Huntsman Way, Potomac, MD 20854 (30-279-7896) Vice President: Janet Millenson, 0500 Falls Road, Potomac, MD 20854 (30-983-9337) Treasurer: Shiras Guion,8007 Martown Road, Laurel, MD 20723 (30-490-0444) Secretary: Janet Shields, 305 Fountain Head Rd, Hagerstown 2742 (30-46-709) Past Pres.: Karen Morley, 279 N. Calvert St., Baltimore, MD 228 (40-235-400) STATE DIRECTORS Allegany: * Barbara Gaffney Howard: * Kurt Schwarz Mary-Jo Betts Anne Arundel: * Paul Speyser Karen Darcy Linda Baker Darius Ecker Al Haury Kent: * Peter Mann Baltimore: * Peter Webb Walter Ellison Jeanne Bowman Mary Chetelat Montgomery: * Sam Freiberg Helene Gardel Don Messersmith John Landers Don Simonson Rick Sussman Caroline: * Bill Scudder Ann Weeks Danny Poet Patuxent: * Frederick Fallon Carroll: * Amy Hoffman Chandler Robbins Roxann Yeager Talbot: * Mark Scallion Cecil: * Rick Lee Shirley Bailey Marcia Watson-Whitmyre William Novak Frederick: * David Smith Tri-County: * Samuel Dyke Michael Welch Elizabeth Pitney Harford: * Jean Wheeler Washington Co.: * Judy Lilga Thomas Congersky Ann Mitchell Randy Robertson *Chapter President Active Membership: $0.00 plus chapter dues Life: $400.00 (4 annual installments) Household: $5.00 plus chapter dues Junior (under 8): $5.00 plus chapter Sustaining: $25.00 plus chapter dues Cover: Pied-billed Grebe, March 1989. Photo by Luther C. Goldman. September–December 2003 MARYLAND BIRDLIFE 3 VOLUME 59 SEPTEMBER–DECEMBER 2003 NUMBERS 3–4 Late NESTING Dates IN Maryland: PINE WARBLER, Northern Parula AND BLUE-Gray Gnatcatcher JAY M. -

Sharon Francis Oral History Interview I, 9/5/80, by Dorothy Pierce Mcsweeney, Internet Copy, LBJ Library

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION The LBJ Library Oral History Collection is composed primarily of interviews conducted for the Library by the University of Texas Oral History Project and the LBJ Library Oral History Project. In addition, some interviews were done for the Library under the auspices of the National Archives and the White House during the Johnson administration. Some of the Library's many oral history transcripts are available on the INTERNET. Individuals whose interviews appear on the INTERNET may have other interviews available on paper at the LBJ Library. Transcripts of oral history interviews may be consulted at the Library or lending copies may be borrowed by writing to the Interlibrary Loan Archivist, LBJ Library, 2313 Red River Street, Austin, Texas, 78705. SHARON FRANCIS ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW I PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, Sharon Francis Oral History Interview I, 9/5/80, by Dorothy Pierce McSweeney, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Diskette from the LBJ Library: Transcript, Sharon Francis Oral History Interview I, 9/5/80, by Dorothy Pierce McSweeney, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY Legal Agreement Pertaining to the Oral History Interviews of Sharon Francis In accordance with the provisions of Chapter 21 of Title 44, United States Code and subject to the terms and conditions hereinafter set forth, I, Sharon Francis of Charlestown, New Hampshire do hereby give, donate and convey to the United States of America all my rights, title and interest in the tape recordings and transcripts of the personal interviews conducted on May 20, June 4, June 27, and August 20, 1969 in Washington, D.C. -

A Community Approach to Managing Manure in the Buffalo River

Section 319 Success Stories Volume III: The Successful Implementation of the Clean Water Act’s Section 319 Nonpoint Source Pollution Program Section 319 Success Stories Volume III: The Successful Implementation of the Clean Water Act’s Section 319 Nonpoint Source Pollution Program For copies of this document, contact: National Service Center for Environmental Publications Phone: 1-800-490-9198 Fax: 513-489-8695 web: www.epa.gov/ncepihom or visit the web at: www.epa.gov/owow/nps United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water 4503F Washington, DC 20460 EPA 841-S-01-001 February 2002 Section 319 Success Stories Volume III: The Successful Implementation of the Clean Water Act’s Section 319 Nonpoint Source Pollution Program United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water Washington, DC Contents Section 319 Success Stories: 1 The Successful Implementation of the Clean Water Act’s Section 319 Nonpoint Source Pollution Program ALABAMA Flint Creek Watershed Project: 7 Multiagency Effort Results in Water Quality Improvements Tuscumbia-Fort Payne Aquifer Protection Program: 8 Multiagency, Cooperative Approach Protects Aquifer ALASKA Restoration Work on the Kenai: 10 Section 319 Funds Are Key to Youth Restoration Corps’s Success Road and Stream Crossing Project in Tongass National Forest: 11 New Data Help Identify Needed Fish Habitat Restoration AMERICAN SAMOA Nu’uuli Pala Lagoon Restoration Project: 12 Efforts Spread to Other Island Villages ARIZONA Restoration in Nutrioso Creek: 13 Successful Results Beginning to Show -

Read Application

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Regist er Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Kingman Park Historic District________________________________ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multip le property listing: Spingarn, Browne, Young, Phelps Educational Campus; Spingarn High School; Langston Golf Course and Langston Dwellings ______________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Western Boundary Line is 200-800 Blk 19th Street NE; Eastern Boundary Line is the Anacostia River along Oklahoma Avenue NE; Northern Boundary Line is 19th- 22nd Street & Maryland Avenue NE; Southern Boundary Line is East Capitol Street at 19th- 22nd Street NE. City or town: Washington, DC__________ State: ____DC________ County: ____________ Not For Publicatio n: Vicinity: ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

DC Citizen Science Water Quality Monitoring Report 2 0 2 0 Table of Contents Dear Friends of the River

WAter DC Citizen Science Water Quality Monitoring Report 2 0 2 0 Table of Contents Dear Friends of the River, On behalf of Anacostia Riverkeeper, I am pleased to share with you our first Annual DC Citizen Science Volunteer Water Quality Report on Bacteria in District Waters. This report focuses on 2020 water quality results from all three District watersheds: the Anacostia River, Potomac River, and Rock Creek. The water quality data we collected is critical for understanding the health of the Anacostia River and District waters; as it serves as a gauge for safe recreation potential as well as a continuing assessment of efforts in the Methodology District of Columbia to improve the overall health of 7 our streams and waterways. As a volunteer program, we are dependent on those who offer time out of their daily schedule to work 8 Anacostia River with us and care for the water quality. With extreme gratitude, we would like to thank all our volunteers and staff for the dedication, professionalism, and enthusiasm to execute this program and to provide high quality data to the public. Additionally, support 10 Potomac River from our partner organizations was crucial to running this program, so we would like to extend an additional thanks to staff at Audubon Naturalist Society, Potomac Riverkeeper, and Rock Creek 12 Rock Creek Conservancy. We hope you find this annual report a good guide to learning more about our local DC waterways. We believe that clean water is a benefit everyone should experience, one that starts with consistent and 14 Discussion publicly available water quality data. -

Careers Start Here

Careers start here. Perhaps never before in the history of America has the importance of education been so much in the forefront. President Obama, in his first state-of-the-union address, called for every American to complete at least one year MCC’s Mission of college. The mission of Mohave Community College is to serve students and The American Council on Education has created a communities by providing an national project called Solutions for Our Future to environment for educational increase awareness of the need for America to improve excellence, innovation and the quality of education and raise the level of education so that this country can awareness. better compete in the global market. MCC’s Goal At MCC we salute you for your interest in higher education. Your time spent with us Mohave Community College strives will improve your life, your earning power and the long-term health of well-being of to provide high quality, affordable your family – even if you haven’t started a family yet. and accessible higher education to all who seek it. As a community college, MCC serves people of all ages and with many different goals. MCC can be your first step toward a bachelor’s, master’s or doctorate degree. Reaching out to serve all of Core academic classes at MCC transfer seamlessly to more than a dozen universities Mohave County and neighboring offering both traditional and online degrees. communities, Mohave Community College’s district covers more than Students who complete an associate of arts, business or science at MCC are 13,000 square miles and includes automatically accepted at our state universities – and with university admission such sites as the Colorado River and requirements getting more stringent, that can be a marked advantage for students. -

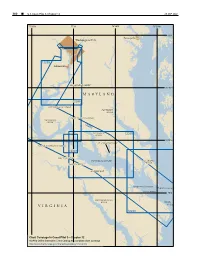

M a R Y L a N D V I R G I N

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 26 SEP 2021 77°20'W 77°W 76°40'W 76°20'W 39°N Annapolis Washington D.C. 12289 Alexandria PISCATAWAY CREEK 38°40'N MARYLAND 12288 MATTAWOMAN CREEK PATUXENT RIVER PORT TOBACCO RIVER NANJEMOY CREEK 12285 WICOMICO 12286 RIVER 38°20'N ST. CLEMENTS BAY UPPER MACHODOC CREEK 12287 MATTOX CREEK POTOMAC RIVER ST. MARYS RIVER POPES CREEK NOMINI BAY YEOCOMICO RIVER Point Lookout COAN RIVER 38°N RAPPAHANNOCK RIVER Smith VIRGINIA Point 12233 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 3—Chapter 12 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 3, Chapter 12 ¢ 301 Chesapeake Bay, Potomac River (1) This chapter describes the Potomac River and the above the mouth; thence the controlling depth through numerous tributaries that empty into it; included are the dredged cuts is about 18 feet to Hains Point. The Coan, St. Marys, Yeocomico, Wicomico and Anacostia channels are maintained at or near project depths. For Rivers. Also described are the ports of Washington, DC, detailed channel information and minimum depths as and Alexandria and several smaller ports and landings on reported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), these waterways. use NOAA Electronic Navigational Charts. Surveys and (2) channel condition reports are available through a USACE COLREGS Demarcation Lines hydrographic survey website listed in Appendix A. (3) The lines established for Chesapeake Bay are (12) described in 33 CFR 80.510, chapter 2. Anchorages (13) Vessels bound up or down the river anchor anywhere (4) ENCs - US5VA22M, US5VA27M, US5MD41M, near the channel where the bottom is soft; vessels US5MD43M, US5MD44M, US4MD40M, US5MD40M sometimes anchor in Cornfield Harbor or St. -

Site for Airport Area Sought

5 Hurt in Crash Site for Airport Horse Racing Brings Maryland Alexandria Tax $5,095,324 Revenue in Year Pofoifllt >y tti* Associated Press Bowie Havre de Group on paid $1,054,656; Pr6m odeheof Labrador Crash Of Two Autos In Less Settled ANNAPOLIS, Dec. 13.—Controllei Grace, $1,059,503; Bel Air. $153,535; On Businesses. James J. Lacy announced yesterdaj Cumberland. $103,847; Hagerstown, State revenues from horse racing $99,571: Marlboro, $124,002. and Ti- 1947 totaled $5,095,324. monium, $125,815. Incidental fees Sees GoalN. of during Sixteenth Street Area Because of the new law taxing brought in $9,173. to the To Be Sought racing, there were no comparable According law, Baltimore Revised figures available, but Mr. Lacy said City and the counties will receive Woman's Head $2,396,094 of Planners Eliminate receipts during the fall meets were the total, the Fair Council to Get Plan Pollution Control Board, and the above expectations. $245,978, general Goes Lake fund, $2,453,251. A Through Kingman Isle, Under the law, Baltimore and the $72,280 refund Basing Levies on for 1946 overpayment at Pimlico Steps Under counties receive 50 per cent of the Way Windshield 2 Other Possibilities was paid by the State. revenues at mile tracks—divided on Gross Receipts Under the new legislation, the To Clean River A 23-year-old woman was In a population basis—and the State': By Nelson M. major tracks now pay a $1,000 daily A new Alexandria business ta: "fair” condition today after a head- Shepard general fund gets the rest. -

Model Selection and Justification Technical Memorandum

Technical Memorandum Model Selection and Justification Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................1 2. Purpose ....................................................................................................................................................1 3. Technical Approach................................................................................................................................ 2 4. Results and Discussion .........................................................................................................................15 Analysis References .................................................................................................................................................. …17 Attachments .................................................................................................................................................. 19 Comprehensive Baseline Comprehensive – , 2014 , December 22 December Consolidated TMDL Implementation Plan Implementation TMDL Consolidated Technical Memorandum: Model Selection and Justification List of Tables Table 1: Modeling Approach used in Mainstem Waterbodies for MS4 Areas ............................................... 4 Table 2: Modeling Approach used in Tributary Waterbodies for MS4 Areas ................................................ 4 Table 3: Modeling Approach used in Other Waterbodies for MS4 Areas ..................................................... -

Candidate Sites CANDIDATE SITES

33 Candidate Sites CANDIDATE SITES Candidate sites were evaluated by applying the specific urban design, economic, With Prime Sites listed first, the 100 candidate sites are: transportation, and environmental criteria defined in Section 3 (for Site Evaluation Criteria, see the technical master plan material, posted on NCPC’s website at www. Candidate Memorial and Museum Sites ncpc.gov). The following Prime Site evaluations were conducted based both on site reconnaissance and using data obtained from NCPC and other sources. No. General Location/Description In addition to these 20 prime sites, 80 additional sites are considered within this mas- Note: Sites #1 through 20 represent the Prime Sites ter plan. Those additional sites are included at the end of the Prime Site evaluations 1 Memorial Avenue at George Washington Memorial Parkway and provide overview assessments of each site's potential to accommodate future (west of Memorial Bridge ) memorials and museums. 2 E Street expressway interchange on the east side of the Kennedy Center 3 Intersection of Maryland and Independence Avenues, SW The diagram below illustrates the approximate location of the 20 Prime Sites within (between 4th and 6th Streets) the master plan framework's Waterfront Crescent, Monumental Corridors, and 4 Kingman Island (Anacostia River) Commemorative Focus Areas. 5 Freedom Plaza on Pennsylvania Avenue, NW between 13th -14th Streets 6 Potomac River waterfront on Rock Creek Parkway (south of the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge) 7 East Capitol Street east of 19th Street (north -

Index 1972 Articles

i GRIST INDEX 1972 ARTICLES page page page ACCIDENTS Do it yourself environmental Litter pick up. Reflectors used in prevention of handbook 66 an aid to 14 deer-auto aceidents 3 Drinking fountain from tree stump 4 Wildlife-auto 3 Drum competition 53,68 Adapter, fasten 2-prong adapter to appliance .... 30 MARKER, barrier 72 Aeration, bottom water out 71 Medium has a message 61 Aerosol can safety 55 ELECTRIC paint mixer 72 Mosquito "thermometer" 3 AM transmitting devices the medium Electrically, on being charged 63 Motor watchmen 68 has a message 61 Engraver modification for copy Anchors, scratchless, quite 50 enlarging 41 Archery, fun but dangerous 45 Environmental study areas 24 Ash trays, portable, featherweight 21 Environmental education NAME plates, Automatic sewage sampling 29 Environmental handbook 66 salvage broken 31 Automatic motor watchmen 68 Expand concept of environmental National Parks Centennial Axes, pulaskis 21 education 26 1872-1972 1.12 Environmental effects of off-road National Recreation & Park Asso., vehicles 2 Grist Awards 69 Eutrophication, bottom water out 71 Noise pollution 2 Non-slip treading for vehicles 10 BARRIER marker 72 Bears, safe release of 16 Biological waste systems 56 Birds, housing project for the 41 FUSES, Blasting caps, on being charged 63 Charge for electricity by fuse size 57 Boating, learn at home 46 Film programs, ON-THE-RUN roadside litter catch 5 Boating safety reminders 47 useful tips for 41 Order out of chaos in the pickup 22 Body splint, one-man application 47 Fire danger-dry grass, pine -

Our Unfair Share 3

Our Unfair Share 3: Race & Pollution in Washington, D.C. African American Environmentalist Association 2000 The African American Environmentalist Association (AAEA), founded in 1985, is dedicated to protecting the environment, enhancing the human ecology, promoting the efficient use of natural resources and increasing African American participation in the environmental movement. AAEA is one of the nation's oldest African American-led environmental organizations. AAEA’s main goals are to deliver environmental information and services directly into the black community. AAEA works to clean up neighborhoods by implementing toxics education, energy, water and clean air programs. AAEA includes an African American point of view in environmental policy decision-making. AAEA resolves environmental racism and environmental justice issues through the application of practical environmental solutions. Our Unfair Share 3: Race and Pollution in Washington, D.C. Author Norris McDonald President Sulaiman Mahdi Contributing Editor Research Assistant Pamela Pittman Administrative Assistant Pamela Jones Editing Red Letter Group, Inc Editing Assistance Ronald Taylor Contributing Scientists Dr. Felix Nwoke Dr. Gustave Jackson © 2000 by the African American Environmentalist Association. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the African American Environmentalist Association. Funding for his report was provided by a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Environmental Justice and Friends of AAEA. The views, recommendations and opinions expressed in this report are those of the African American Environmentalist Association and do not necessarily reflect the views, recommendations or opinions of the U.S.