Duke University Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories

Complexity in the Comic and Graphic Novel Medium: Inquiry Through Bestselling Batman Stories PAUL A. CRUTCHER DAPTATIONS OF GRAPHIC NOVELS AND COMICS FOR MAJOR MOTION pictures, TV programs, and video games in just the last five Ayears are certainly compelling, and include the X-Men, Wol- verine, Hulk, Punisher, Iron Man, Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Watchmen, 300, 30 Days of Night, Wanted, The Surrogates, Kick-Ass, The Losers, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, and more. Nevertheless, how many of the people consuming those products would visit a comic book shop, understand comics and graphic novels as sophisticated, see them as valid and significant for serious criticism and scholarship, or prefer or appreciate the medium over these film, TV, and game adaptations? Similarly, in what ways is the medium complex according to its ad- vocates, and in what ways do we see that complexity in Batman graphic novels? Recent and seminal work done to validate the comics and graphic novel medium includes Rocco Versaci’s This Book Contains Graphic Language, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics. Arguments from these and other scholars and writers suggest that significant graphic novels about the Batman, one of the most popular and iconic characters ever produced—including Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley’s Dark Knight Returns, Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum, and Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s Killing Joke—can provide unique complexity not found in prose-based novels and traditional films. The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011 r 2011, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

'Jo També Sóc Catalana' by Najat El Hachmi

Mètode Science Studies Journal ISSN: 2174-3487 [email protected] Universitat de València España Segarra, Marta MIGRANT LITERATURE. ‘JO TAMBÉ SÓC CATALANA’ BY NAJAT EL HACHMI Mètode Science Studies Journal, núm. 5, 2015, pp. 75-79 Universitat de València Valencia, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=511751360011 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MONOGRAPH MÈTODE Science Studies Journal, 5 (2015): 75-79. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.81.3146 ISSN: 2174-3487. Article received: 19/12/2013, accepted: 27/03/2014. MIGRANT LITERATURE ‘JO TAMBÉ SÓC CATALANA’ BY NAJAT EL HACHMI MARTA SEGARRA This article discusses «migrant literature» in Catalonia, looking at the particular case of Najat El Hachmi, a Catalan writer of Moroccan origin. Here we analyse her fi rst book, the auto-biographical Jo també sóc catalana (“I Am Also Catalan”) by examining how the migratory experience is expressed from a linguistic, cultural and gender perspective. We also compare her case with that of other writers, especially those belonging to the so-called «Francophone Maghreb» literature. Keywords: migrant literature, Catalan literature, Maghreb literature, Najat El Hachmi. The migratory experience, with all its social, countries but who settled in Catalonia and chose economic and, above all, emotional and psychological to write in Catalan. They could fi t into the category complexities, has become a major literary and artistic of «migrant literature», not only attending to the theme, especially in recent decades. -

Pacini, Parody and Il Pirata Alexander Weatherson

“Nell’orror di mie sciagure” Pacini, parody and Il pirata Alexander Weatherson Rivalry takes many often-disconcerting forms. In the closed and highly competitive world of the cartellone it could be bitter, occasionally desperate. Only in the hands of an inveterate tease could it be amusing. Or tragi-comic, which might in fact be a better description. That there was a huge gulf socially between Vincenzo Bellini and Giovanni Pacini is not in any doubt, the latter - in the wake of his highly publicised liaison with Pauline Bonaparte, sister of Napoleon - enjoyed the kind of notoriety that nowadays would earn him the constant attention of the media, he was a high-profile figure and positively reveled in this status. Musically too there was a gulf. On the stage since his sixteenth year he was also an exceptionally experienced composer who had enjoyed collaboration with, and the confidence of, Rossini. No further professional accolade would have been necessary during the early decades of the nineteenth century On 20 November 1826 - his account in his memoirs Le mie memorie artistiche1 is typically convoluted - Giovanni Pacini was escorted around the Conservatorio di S. Pietro a Majella of Naples by Niccolò Zingarelli the day after the resounding success of his Niobe, itself on the anniversary of the prima of his even more triumphant L’ultimo giorno di Pompei, both at the Real Teatro S.Carlo. In the Refettorio degli alunni he encountered Bellini for what seems to have been the first time2 among a crowd of other students who threw bottles and plates in the air in his honour.3 That the meeting between the concittadini did not go well, this enthusiasm notwithstanding, can be taken for granted. -

“Between Borders: Moroccan Migrations in L'últim Patriarca By

“Between Borders: Moroccan Migrations in L’últim patriarca by Najat El-Hachmi” A Lecture by Kathleen McNerney Prize-winning translator of women’s writing from Catalonia Wednesday April 24, 2019 4pm 1301 Rolfe Hall, UCLA Born in Morocco in 1979, Najat El Hachmi immigrated with her family to the Barcelona area when she was a child. She attended Catalan schools and then studied Arabic literature at the University of Barcelona. Her first book, Jo també sóc catalana (2004), is autobiographical, dealing with issues of identity and belonging in a new place. In 2008, the novel L’últim patriarca won the very prestigious Ramon Llull Prize for Catalan Literature and was soon translated into English. Mare de llet i mel is her most recent work. Kathleen McNerney is professor emerita of Spanish and Women’s Studies at West Virginia University, where she was Benedum Distinguished Scholar and Singer Professor of the Humanities. She has awarded several prizes in Catalonia for her work, including the Premi Batista i Roca from the Institut de Projecció Exterior. Her work includes Latin American, Castilian, and French literatures, but focuses on Catalan women authors. She is coeditor of Double Minorities of Spain (MLA 1994) and Visions and Revisions: Women’s Narrative in Twentieth-Century Spain (Rodopi 2008). She has also edited collections of essays on Mercè Rodoreda and is translator of stories, poetry, and four novels. Her latest publication is Silent Souls and Other Stories (MLA 2018) by Caterina Albert, which has just been awarded the translation prize by the North American Catalan Society. In her talk, McNerney will focus on Najat El Hachmi’s novels. -

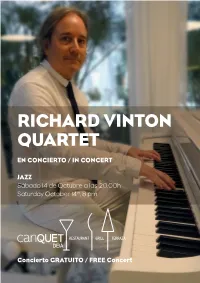

Richard Vinton Quartet

CONCIERTO GRATUITO CAN QUET ABRE A LAS 19:00 H Y EL CONCIERTO COMIENZA A LAS 20:00 H. LA COCINA ESTÁ ABIERTA DESDE LAS 19.00 H. FREE CONCERT CAN QUET OPENS AT 7 P.M. AND THE CONCERT STARTS AT 8 P.M. THE KITCHEN OPENS ON 7 P.M. RICHARD VINTON QUARTET EN CONCIERTO / IN CONCERT Ctra. Valldemossa-Deià, s/n. JAZZ 07179 - Deià - Illes Balears Sábado 14 de Octubre a las 20.00h Tel: (+34) 971 639 196 Saturday October 14th, 8 pm [email protected] www.restaurantecanquet.com @canquetdeya Abierto: Miércoles a Domingo 19:00 a 24:00 h Parking para Clientes Concierto GRATUITO / FREE Concert RICHARD VINTON piano RICHARD VINTON piano El conocido pianista, arreglista y educador nació en Florida, The well-known pianist, arranger and educator was born in Florida, USA. Apart EEUU. Aparte de sus Bachelors de Música del New England from his Music Bachelors of the New England Conservatory in Boston and his Conservatory en Boston y su Masters de Música de la University Masters of Music from the University of Miami he studied jazz piano and com- of Miami estudió jazz piano y composición en la Berklee College position at the Berklee College of Music and worked among others with the of Music y trabajó entre otros con the Mavericks y Tony Bennett. Mavericks and Tony Bennett. En Mallorca Richard ha colaborado con The Drifters (Son Amar), Richard, who lives in Mallorca since twenty years, has collaborated with The Drifters Come Fly With Me (Gran Casino Mallorca), Michelle McCain, (Son Amar), Come Fly With Me (Gran Casino Mallorca), Michelle McCain, Jaime An- Jaime Anglada, Conxa Buika, Cap Pella y la Orquestra Simfònica glada, Conxa Buika, Cap Pella and the Symphony Orchestra of the Balearic Islands. -

Humor & Classical Music

Humor & Classical Music June 29, 2020 Humor & Classical Music ● Check the Tech ● Introductions ● Humor ○ Why, When, How? ○ Historic examples ○ Oddities ○ Wrap-Up Check the Tech ● Everything working? See and hear? ● Links in the chat ● Zoom Etiquette ○ We are recording! Need to step out? Please stop video. ○ Consider SPEAKER VIEW option. ○ Please remain muted to reduce background noise. ○ Questions? Yes! In the chat, please. ○ We will have Q&A at the end. Glad you are here tonight! ● Steve Kurr ○ Middleton HS Orchestra Teacher ○ Founding Conductor - Middleton Community Orchestra ○ M.M. and doctoral work in Musicology from UW-Madison ■ Specialties in Classic Period and Orchestra Conducting ○ Continuing Ed course through UW for almost 25 years ○ Taught courses in Humor/Music and also performed it. WHAT makes humorous music so compelling? Music Emotion with a side order of analytical thinking. Humor Analytical thinking with a side order of emotion. WHY make something in music funny? 1. PARODY for humorous effect 2. PARODY for ridicule [tends toward satire] 3. Part of a humorous GENRE We will identify the WHY in each of our examples tonight. HOW is something in music made funny? MUSIC ITSELF and/or EXTRAMUSICAL ● LEVEL I: Surface ● LEVEL II: Intermediate ● LEVEL III: Deep We will identify the levels in each of our examples tonight. WHEN is something in music funny? ● Broken Expectations ● Verisimilitude ● Context Historic Examples: Our 6 Time Periods ● Medieval & Renaissance & Baroque ○ Church was primary venue, so humor had limits (Almost exclusively secular). ● Classic ○ Music was based on conventions, and exploration of those became the humor of the time. ● Romantic ○ Humor was not the prevailing emotion explored--mainly used in novelties. -

Piraten- Und Seefahrerfilm 2011

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Matthias Christen; Hans Jürgen Wulff; Lars Penning Piraten- und Seefahrerfilm 2011 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12750 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Christen, Matthias; Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Penning, Lars: Piraten- und Seefahrerfilm. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2011 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 120). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12750. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0120_11.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Piraten- und Seefahrerfilme // Medienwissenschaft/Hamburg 120, 2011 /// 1 Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 120, 2011: Piraten- und Seefahrerfilm. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Matthias Christen, Hans J. Wulff, Lars Penning. ISSN 1613-7477. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0120_11.html Letzte Änderung: 28.4.2011. Piratenfilm: Ein Dossier gentlichen Piraten trennen, die „gegen alle Flaggen“ segelten und auf eigene Rechnung Beute machten. Inhalt: Zur Einführung: Die Motivwelt des Piratenfilms / Matthi- Selbst wenn die Helden und die sehr seltenen Hel- as Christen. dinnen die Namen authentischer Piraten wie Henry Piratenfilm: Eine Biblio-Filmographie. / Hans J. Wulff. Morgan, Edward Teach oder Anne Bonny tragen und 1. Bibliographie. 2. Filmographie der Piratenfilme. ihre Geschichte sich streckenweise an verbürgte Tat- Filmographie der Seefahrerfilme / Historische Segelschif- sachen hält, haben Piratenfilme jedoch weniger mit fahrtsfilme / Lars Penning. -

El Ritmo De Las Palabras: Concha Buika

MUSIC El ritmo de las palabras: NEW YORK Concha Buika Wed, June 17, 2015 7:00 pm Venue Instituto Cervantes, 211 East 49th Street, New York, NY 10017 View map Phone: 212-308-7720 Admission Free admission, limited seating. RSVP required at [email protected] by Tuesday, June 16. More information Instituto Cervantes New York The Spanish Grammy winning artist Concha Buika will Credits ‘perform’ poems, stories and chants from her recent book, A Organized by the Consulate general of Spain in New York, Instituto los que amaron a mujeres difíciles y acabaron por soltarse. Cervantes New York and Books & Books. Born in Palma de Mallorca, Spain, as the daughter of African parents and hailed as a star in contemporary world music, jazz, flamenco, and fusion, Buika posesses a unique blend of influences as well as a remarkable voice –raw and smoky, but with a tenderness that hits right at the heart, vibrantly deploying her rich, sensual and husky instrument. In 2011, NPR listed her spellbinding sound among its 50 Great Voices, calling hers the voice of freedom. She has received multiple awards and nominations, such as Latin Grammys for Best Album and Best Production for Niña de Fuego and Best Traditional Tropical Album for El Último Trago, and she was nominated again in 2014 for Record of the Year for La Noche Más Larga and for Best Latin Jazz Album at the 2014 Grammy Awards. Book purchase necessary to attend. Book signing after the event. Embassy of Spain – Cultural Office | 2801 16th Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20009 | Tel: (202) 728-2334 View this event online: https://www.spainculture.us/city/new-york/el-ritmo-de-las-palabras-concha-buika/ Created on 09/27/2021 | Page 1 of 1. -

Estrella Morente Lead Guitarist: José Carbonell "Montoyita"

Dossier de prensa ESTRELLA MORENTE Vocalist: Estrella Morente Lead Guitarist: José Carbonell "Montoyita" Second Guitarist: José Carbonell "Monty" Palmas and Back Up Vocals: Antonio Carbonell, Ángel Gabarre, Enrique Morente Carbonell "Kiki" Percussion: Pedro Gabarre "Popo" Song MADRID TEATROS DEL CANAL – SALA ROJA THURSDAY, JUNE 9TH AT 20:30 MORENTE EN CONCIERTO After her recent appearance at the Palau de la Música in Barcelona following the death of Enrique Morente, Estrella is reappearing in Madrid with a concert that is even more laden with sensitivity if that is possible. She knows she is the worthy heir to her father’s art so now it is no longer Estrella Morente in concert but Morente in Concert. Her voice, difficult to classify, has the gift of deifying any musical register she proposes. Although strongly influenced by her father’s art, Estrella likes to include her own things: fados, coplas, sevillanas, blues, jazz… ESTRELLA can’t be described described with words. Looking at her, listening to her and feeling her is the only way to experience her art in an intimate way. Her voice vibrates between the ethereal and the earthly like a presence that mutates between reality and the beyond. All those who have the chance to spend a while in her company will never forget it for they know they have been part of an inexplicable phenomenon. Tonight she offers us the best of her art. From the subtle simplicity of the festive songs of her childhood to the depths of a yearned-for love. The full panorama of feelings, the entire range of sensations and colours – all the experiences of the woman of today, as well as the woman of long ago, are found in Estrella’s voice. -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ...............................................