Aalborg Universitet Local Food for International Tourists Explorative Studies of Perceptions of Networking and Interactions in T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the SKIVE AREA

TIPS FOR WALKING AND CYCLING TRIPS ADRENALINE KICKS AND MOMENTS NEW IN THE AREA? SAFE ENVIRONMENT OF PEACE Guide to the SKIVE AREA A HUB FOR GREEN ACTION PURE LIFE BECOME PART OF THE COMMUNITY SKIVE IN FIGURES EXPLORE THE AREA SKIVE MUNICIPALITY PAGE 03 Welcome to the PURE LIFE WELCOME TO THE SKIVE AREA The Skive Area is a special place to live. It lets you lead a greener life – both via its unique countryside and leading position in terms of climate-friendly solutions. Strong communities, good schools and an active business com- SKIVE munity are some of the elements that characterise the area. In the Skive Area you will find desirable residences and building sites which will form a basis for your everyday life here. The urban development project BigBlue Skive is priming Skive for a more climate-friendly future and uniting the city on both sides of the picturesque river. And finally, development projects AREA in the rural areas are creating a framework for new strong communities. No matter where you choose to live, you will always be close to nature with green woods, wide heathlands and THE LIMFJORD that is never more than 12 kilometres away, as the crow flies. The area is connected geographically by the surrounding fjord. And with a 199-kilometre stretch of coast (that is more than four metres for each resident) and six active harbours, the Skive Area provides ample opportunity for you to fulfil your dream of living by or close to the sea. �⟶ STRETCH OF COAST AREA 199 kilometres 684km2 With more than four metres of coast for each resident This results in a pop- and six active harbours, the area provides ample op- ulation density of 67 portunity for you to fulfil your dream of living by the sea. -

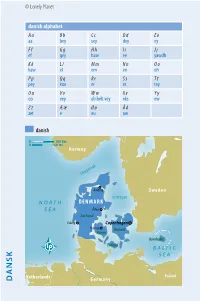

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Oversigt Over Retskredsnumre

Oversigt over retskredsnumre I forbindelse med retskredsreformen, der trådte i kraft den 1. januar 2007, ændredes retskredsenes numre. Retskredsnummeret er det samme som myndighedskoden på www.tinglysning.dk. De nye retskredsnumre er følgende: Retskreds nr. 1 – Retten i Hjørring Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten i Aalborg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Randers Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Aarhus Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Viborg Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Holstebro Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Herning Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Horsens Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Kolding Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Esbjerg Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Sønderborg Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Odense Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Svendborg Retskreds nr. 14 – Retten i Nykøbing Falster Retskreds nr. 15 – Retten i Næstved Retskreds nr. 16 – Retten i Holbæk Retskreds nr. 17 – Retten i Roskilde Retskreds nr. 18 – Retten i Hillerød Retskreds nr. 19 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. 20 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 21 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 22 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 23 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 24 – Retten på Bornholm Indtil 1. januar 2007 havde retskredsene følende numre: Retskreds nr. 1 – Københavns Byret Retskreds nr. 2 – Retten på Frederiksberg Retskreds nr. 3 – Retten i Gentofte Retskreds nr. 4 – Retten i Lyngby Retskreds nr. 5 – Retten i Gladsaxe Retskreds nr. 6 – Retten i Ballerup Retskreds nr. 7 – Retten i Hvidovre Retskreds nr. 8 – Retten i Rødovre Retskreds nr. 9 – Retten i Glostrup Retskreds nr. 10 – Retten i Brøndbyerne Retskreds nr. 11 – Retten i Taastrup Retskreds nr. 12 – Retten i Tårnby Retskreds nr. 13 – Retten i Helsingør Retskreds nr. -

TAL OG FAKTA Udviklingstræk

Udvalget for Landdistrikter og Øer 2014-15 ULØ Alm.del Bilag 22 Offentligt Sammen gør vi en forskel TAL OG FAKTA Udviklingstræk Jammerbugt Kommune har ca. 38.300 ind- Jammerbugtens land mellem hav og fjord byggere. Jammerbugt Kommune dækker et er præget af havet, fjorden og grænseflader areal på 863 km2. mellem Thy og Vendsyssel og nærheden til Jammerbugt Kommune er en lang kommu- Aalborg. ne. Fra Vust i vest til Ingstrup i nord/øst er De naturgivne forhold har på forskellig cirka 60 kilometer. Kommunen er dog ingen måde påvirket udviklingen i forskellige steder mere end 20 km bred – fra fjord til hav. tidsperioder. Der er kæmpet mange kam- pe om jorden, vandet, vinden - og selv om sandflugt, inddæmninger og læplantnin- Løkken- Vrå ger overvejende hører fortiden til, skal vi i Brønderslev Jammerbugt Kommune fortsat være op- mærksomme på ændringer i klimaet og den måde, hvorpå de kan komme til at påvirke Pandrup Aabybro os i de kommende årtier. Jammerbugt Kommune ligger godt placeret Fjerritslev Brovst tæt på Aalborg. Virksomheder og borgere lever på mange måder af den positive ud- Aalborg vikling, som Aalborg gennemgår som ”Nord- Nibe danmarks Vækstdynamo”. Løgstør 45.000 0 -19 år 20 - 64 år 65 år og over Generelt giver demografien, kompetenceniveau- et og udviklingen på arbejdsmarkedet en række 40.000 udfordringer: • Befolkningen bliver ældre og mange trækker 35.000 sig ud af arbejdsmarkedet i de kommende år • Pendlingen øges ud af kommunen og borge- re pendler over større afstande 30.000 • Der er behov for uddannelse og kompetenceløft • Der er færre jobs til ufaglærte 25.000 • Vi har – som andre – en for stor gruppe bor- gere, der ikke er i arbejde 20.000 Befolkningstallet ligger på 38.300 indbyggere, og vi ser at vi bliver flere ældre og flere flytter mod de større byer. -

The Good Experiences

- Welcome to the good experiences In Denmark, there are 408 campsites with motorhome sites with all the required facilities. The 408 campsites are spread out all over Denmark, so you are never further than approx. 20 km from the nearest motorhome site, no matter where you are in the country. You can arrive at a motorhome site at any time of the day or night. The basic facility offered by a motorhome site is an even, stable pitch on which to park the motorhome. You then have the option of paying for electricity, access to a toilet and shower, filling your water tank with clean water and emptying your waste tank. The cost of staying at one of the many motorhome sites varies from site to site. Some motorhome sites, for example, charge an hourly rate of DKK 8 for the basic pitch, while others charge DKK 100 for the period from 8 pm to 10 am for the basic pitch. The 408 campsites with motorhome sites allow you to experience everything Denmark has to offer as a country. You can visit old towns and cities and experience the unique nature such as Møns Klint, Skagen, Bornholm or Thy National Park, the beaches on the west coast, the Baltic and the Kattegat or farm shops selling local produce. Motorhome Guide Denmark welcomes you to wonderful experiences. Page 1 of 10 Address Place Zip City Phone Region Haregade 23 3720 Aakirkeby 56975551 Bornholm Klynevej 6 Balka 3730 Neksø 56488074 Bornholm Duegårdsvej 2 Dueodde 3730 Nexø 56488149 Bornholm Skrokkegårdsvej 17 Dueodde 3730 Nexø 20146849 Bornholm Sydskovvej 9 3740 Svaneke 56496363 Bornholm Melsted Langgade 45 3760 Gudhjem 56485071 Bornholm Borrelyngvej 43 3770 Allinge 56480574 Bornholm Sandlinien 5 Sandvig 3770 Allinge 56480447 Bornholm Poppelvej 2 Sandkaas 3770 Allinge 56480441 Bornholm Fælledvej 30 3790 Hasle 56945300 Bornholm Odensevej 102 5260 Odense S. -

Connecting Øresund Kattegat Skagerrak Cooperation Projects in Interreg IV A

ConneCting Øresund Kattegat SkagerraK Cooperation projeCts in interreg iV a 1 CONTeNT INTRODUCTION 3 PROgRamme aRea 4 PROgRamme PRIORITIes 5 NUmbeR Of PROjeCTs aPPROveD 6 PROjeCT aReas 6 fINaNCIal OveRvIew 7 maRITIme IssUes 8 HealTH CaRe IssUes 10 INfRasTRUCTURe, TRaNsPORT aND PlaNNINg 12 bUsINess DevelOPmeNT aND eNTRePReNeURsHIP 14 TOURIsm aND bRaNDINg 16 safeTy IssUes 18 skIlls aND labOUR maRkeT 20 PROjeCT lIsT 22 CONTaCT INfORmaTION 34 2 INTRODUCTION a short story about the programme With this brochure we want to give you some highlights We have furthermore gathered a list of all our 59 approved from the Interreg IV A Oresund–Kattegat–Skagerrak pro- full-scale projects to date. From this list you can see that gramme, a programme involving Sweden, Denmark and the projects cover a variety of topics, involve many actors Norway. The aim with this programme is to encourage and and plan to develop a range of solutions and models to ben- support cross-border co-operation in the southwestern efit the Oresund–Kattegat–Skagerrak area. part of Scandinavia. The programme area shares many of The brochure is developed by the joint technical secre- the same problems and challenges. By working together tariat. The brochure covers a period from March 2008 to and exchanging knowledge and experiences a sustainable June 2010. and balanced future will be secured for the whole region. It is our hope that the brochure shows the diversity in Funding from the European Regional Development Fund the project portfolio as well as the possibilities of cross- is one of the important means to enhance this development border cooperation within the framework of an EU-pro- and to encourage partners to work across the border. -

Kortlægning Af Sommerhusområder I Danmark – Med Særligt Henblik På Affaldshåndtering

Kortlægning af sommerhusområder i Danmark – med særligt henblik på affaldshåndtering Fase 1 i projektet ”Effektiv kommunikation - om affaldshåndtering - i sommerhusområder” Udarbejdet for Miljøstyrelsen Titel: Forfattere: Kortlægning af sommerhusområder i Danmark – med Carl Henrik Marcussen, Center for Regional- og særligt henblik på affaldshåndtering Turismeforskning Hans-Christian Holmstrand, Bornholms Affaldsbehandling (BOFA) / Aalborg Universitet Udgiver: Center for Regional og Turismeforskning Stenbrudsvej 55 3730 Nexø År: November 2015 ISBN: 978-87-916-7743-4 (PDF) Indhold Forord ....................................................................................................................... 6 Resume ..................................................................................................................... 7 Summary................................................................................................................... 9 1. Indledning ........................................................................................................ 11 2. Oversigt over sommerhuse og disses anvendelse i de danske landsdele og kommuner ....................................................................................................... 12 2.1 Intro – til oversigtskapitlet baseret på sekundære datakilder ............................................ 12 2.2 Resume af oversigtskapitlet - baseret på foreliggende datakilder ...................................... 12 2.3 Kommenterede tabeller og figurer - oversigtskapitlet -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

We Want You Magazine.Pdf

We Want You 2 City of Aalborg - We Want You City of Aalborg - We Want You 3 We Want You Some cities are huge, dynamic metropolises. Some towns are small and quaint. Others, like Aalborg, are exactly like in the story of Goldi- locks and the Three Bears: just right. In Aalborg, it is truly our expe- in population and workforce, as rience that one size fits all. From thousands of new students and our huge shopping centres to our workers join us every year, result- peaceful harbour front, from our ing in a demographic trend that is pulsating night life to the stillness rendering Aalborg younger of our parks, from our buzzing air- and younger. port to our safe, clean and attrac- tive residential areas - Aalborg has This development is influencing a place to suit any mood. many aspects of life in Aalborg and almost every part of the city Why the sales pitch? Because we where building sites are the visible want you to join our workforce. proof; industrial sites are trans- Your talents and skills are needed formed into homes and offices for in our vibrant business com- knowledge based businesses. munity, in our many public and private companies and organisa- Welcome to our rapidly growing tions. Whatever your profession, city. Whether you’re one of the we’re sure that you’re just right many new citizens in Aalborg or for Aalborg. just considering moving here, know that you are very welcome Judging by Aalborg’s demo- and that you have much to look graphic evolution, you would think forward to. -

Finding the Land of Opportunity Intergenerational Mobility in Denmark

Finding the Land of Opportunity Intergenerational Mobility in Denmark Jesper Eriksen Department of Business and Management Aalborg University 178,866 characters with spaces - 74.5 pages May 31, 2018 Abstract Denne afhandling omhandler lige muligheder inden for intergenerationel mobilitet i en dansk kontekst. Afhandlingen forholder sig til spørgsmålet, “Er lighed i muligheder påvirket af lokalområder i Danmark?”. Jeg besvarer forskningsspørgsmålet ved at undersøge tre under- spørgsmål: (1) “Hvad karakteriserer den geografiske fordeling af muligheder i Danmark?”, (2) “Hvorfor kunne bestemte grupper, defineret ved geografi, forventes at opleve højere eller lavere mobilitet? Hvilken rolle spiller lokalområde karakteristika som forklarende variabel i forhold til lige muligheder?”, og (3) “Hvad er effekten af at flytte fra ét lokal område til et andet for lige muligheder for flyttende familier?“. Først opstiller jeg et teoretisk grundlag for at kunne diskutere lighed i muligheder, som filosofisk begreb, i relation til gængse mål for lighed i muligheder: intergenerationel mobilitet. Jeg påviser, at det ikke er muligt at vurdere, hvorvidt lighed i muligheder påvirkes ud fra nogen af de tre teorier ved alene at undersøge mobilitetsmål. For at besvare forskningsspørgsmålet kræves der information om, hvordan lokalområder kausalt påvirker intergenerationel mobilitet. For at besvare første underspørgsmål beskriver jeg grundlæggende træk i litteraturen om in- tergenerational mobilitet, samt den metodiske literatur om intergenerationel mobilitetsmål. Datagrundlaget for besvarelsen er dansk registerdata for perioden 1980-2012, som tillader kobling af børn og forældre, samt måling af samlet indkomst før skat. Ved at allokere børn født mellem 1973-1975 til de kommuner, som primært vokser op i, fra de er 7-15 viser jeg, at der er substantiel variation i intergenerationel mobilitet på tværs af danske kommuner. -

Coastal Living in Denmark

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Coastal living in Denmark © Daniel Overbeck - VisitNordsjælland To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. The land of endless beaches In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders that we at VisitDenmark are particularly proud of is our nature. Denmark has wonderful beaches open to everyone, and nowhere in the nation are you ever more than 50km from the coast. s. 2 © Jill Christina Hansen To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video Introduction • Denmark’s currency is the Danish Kroner Odense • Tipping is not required Zealand • Most Danes speak fluent English Funen • Denmark is of the happiest countries in the world and Copenhagen is one of the world’s most liveable cities • Denmark is home of ‘Hygge’, New Nordic Cuisine, and LEGO® • Denmark is easily combined with other Nordic countries • Denmark is a safe country • Denmark is perfect for all types of travelers (family, romantic, nature, bicyclist dream, history/Vikings/Royalty) • Denmark has a population of 5.7 million people s. -

Fosdalen Og Langdalen Lerup Kirke Skærer Dalen Sig Ned I Lien

Fosdalen Hederne Fosdalen er et af Hanherreds mest kendte udflugtssteder. Fra plateauet ved Især i Fosdal Plantage er der mange Velkommen til Fosdalen og Langdalen Lerup Kirke skærer dalen sig ned i Lien. Der er flere rastepladser i området, men smukke hedestrækninger, som er for- vil man gå igennem dalen kan det anbefales at starte på pladsen ved kirken. blev et utilplantede. Der er tale om ind- Fosdalen og dens omgivelser har været søgt af mennesker for sit hel- Ganske nær kirken udspringer Vor Frue Kilde, en gammel helligkilde, som landsheder med en række karakteristiske bredende vand i hvert fald siden tidlig middelalder. Måske er det den for- gennem århund reder søgtes af syge på Jomfru Marias fødselsdag, den arter som hedelyng, ene, blåbær, tytte- nemmelse af at træde i forfædrenes fodspor, der giver området sin sær- 8. september. Det gav anledning til det store Lerup Kildemarked, som imid- bær og hede-melbærris. lige virkning og føjer en ekstra dimension til naturens mangfoldighed og lertid udartede til handel, dans, druk og slagsmål. Præsten klagede i 1585 til På de to bakkedrag, som adskilles af landskabets skønhed. Børglumsbispen over ”grov uskikkelighed”, og markedet blev flyttet. I den øvre Lilledal, vokser mængder af planten hønse - Hensyn til naturen. På grund af de særlige naturmæssige forhold er Fosdalen og Langdalen del af Fosdalen vandrer man under et tag af frodig løvskov med fuglesang fra bær, og bevæger man sig op på grav- både, Fosdal og Langdal Plantager udpeget som særligt beskyttede sko- oven og bækkens rislen i dalbunden. Længst nede, hvor dalen er mere åben, er højene, belønnes man med en storslået ve.