When Was Biton?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Foran (Order #10809442) Everyman Unchained: Fighters

Michael Foran (Order #10809442) Everyman Unchained: Fighters Authors: Alexander Augunas Cover Artist: Jacob Blackmon Cover Design: Alexander Augunas Interior Art: Jacob Blackmon Editor: Luis Loza DESIGNATION OF PRODUCT IDENTITY All company names, logos, and artwork, images, graphics, illustrations, trade dress, and graphic design elements and proper names are designated as Product Identity. Any rules, mechanics, illustrations, or other items previously designated as Open Game Content elsewhere or which are in the public domain are not included in this declaration DECLARATION OF OPEN GAME CONTENT All content not designated as Product Identity is declared Open Game Content as de- scribed in Section 1(d) of the Open Game License Version 1.0a. Compatibility with the PATHFINDER ROLEPLAYING GAME requires the PATHFINDER ROLEPLAYING GAME from Paizo Inc.. See http://paizo.com/pathfinderRPG for more information on the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. Paizo Inc. does not guarantee compatibility, and does not endorse this product. Pathfinder is a registered trademark of Paizo Inc., and the PATHFINDER ROLEPLAYING GAME and the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Compatibility Logo are trademarks of Paizo Inc., and are used under the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Compatibility License. See http:// paizo.com/pathfinderRPG/compatibility for more information on the compatibility li- cense. Everyman Unchained: Fighters © 2016 by Everyman Gaming, LLC. ABOUT EVERYMAN GAMING, LLC Everyman Gaming began as the blog of Alexander Augunas in January 2014, where he wrote about Pathfinder Roleplaying Game tips, tricks, and techniques for both players and GMs. In May of 2014, Alex began talks with the Know Direction Network about bringing his blog to their site under the name Guidance. -

Military Engineering 5-6 Syllabus

Fairfax Collegiate 703 481-3080 · www.FairfaxCollegiate.com Military Engineering 5-6 Syllabus Course Goals 1 Physics Concepts and Applications Students learn the basics of physics, including Newton’s laws and projectile motion. They will apply this knowledge through the construction of miniature catapult structures and subsequent analysis of their functions. 2 History of Engineering Design Students learn about the progression of military and ballistics technology starting in the ancient era up until the end of the Middle Ages. Students will identify the context that these engineering breakthroughs arose from, and recognize the evolution of this technology as part of the engineering design process. 3 Design, Fabrication, and Testing Students work in small teams to build and test their projects, including identifying issues and troubleshooting as they arise. Students will demonstrate their understanding of this process through the design, prototyping, testing, and execution of an original catapult design. Course Topics 1 Ancient Era Siege Weapons 1.1 Brief History of Siege Warfare 1.2 Basic Physics 2 The Birth of Siege Warfare 2.1 Ancient Greece 2.2 Projectile Motion 3 Viking Siege! 3.1 History of the Vikings 3.2 Building with Triangles 4 Alexander the Great and Torsion Catapults Fairfax Collegiate · Have Fun and Learn! · For Rising Grades 3 to 12 4.1 The Conquests of Alexander the Great 4.2 The Torsion Spring and Lithobolos 5 The Romans 6 Julius Caesar 7 The Crusades 8 The Middle Ages 9 Castle Siege Course Schedule Day 1 Introduction and Ice Breaker Students learn about the course, their instructor, and each other. -

GURPS Low-Tech, 1St Printing

Covering the Paleolithic to the Age of Sail, GURPS Low-Tech is your guide to TL0-4 equipment for historical adventurers, modern survivalists, post-apocalypse survivors, and time travelers. It surveys current historical and archaeological research to present accurate gear, including: • Weapons. Stone axes, steel blades, muskets, and heavy weapons (from catapults to cannon) to grant a fighting edge whether you face bears, phalanxes, or high-seas pirates. • Armor. Pick coverage, quality, and materials (even exotica like jade!) to suit your budget, and then calculate protection, weight, impact on stealth, and more. • Transportation. Travel aids such as skis and floats; riding gear for horses, camels, and elephants; and vehicles ranging from oxcarts and rafts to war wagons and low-tech submarines. • Survival Gear. Simple tools and local materials to let you find your way, stay warm and dry, and feed yourself in the wilderness. • Tools. Everything you need to gather basic resources, craft finished goods, work in the literate professions, spy, or thieve. • Medicine. Treat illness and injury with herbs, acupuncture, and surgery. GURPS Low-Tech requires the GURPS Basic Set, Fourth Edition. The information on real-world equipment is useful for any campaign set prior to 1730, as well as historical fantasy. By William H. Stoddard, with Peter Dell’Orto, Dan Howard, and Matt Riggsby Edited by Sean Punch Cover Art by Bob Stevlic Illustrated by Alan Azez, Eric J. Carter, Igor Fiorentini, Angela Lowry, Matthew Meyer, Rod Reis, and Bob Stevlic 1ST EDITION, 1ST PRINTING PUBLISHED DECEMBER 2010 ISBN 978-1-55634-802-0 Printed in $29.99 SJG 01-0108 the USA Written by WILLIAM H. -

Adventurer Conqueror King System © 2011–2012 Autarch

TM Game Design by ALEXANDER MACRIS with TAVIS ALLISON and GREG TITO RULES FOR ROLEPLAYING IN A WORLD OF SWORDS, SORCERY, AND STRONGHOLDS FIRST EDITION Adventurer Conqueror King System © 2011–2012 Autarch. The Auran Empire™ and all proper names, dialogue, plots, storylines, locations, and characters relating thereto are copyright 2011 by Alexander Macris and used by Autarch™ under license. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the written permission of the copyright owners. Autarch™, Adventure Conqueror King™, Adventurer Conqueror King System™, and ACKS™ are trademarks of Autarch™. Auran Empire™ is a trademark of Alexander Macris and used by Autarch™ under license. Adventurer Conqueror King System is distributed to the hobby, toy, and comic trade in the United States by Game Salute LLC. This product is a work of fiction. Any similarity to actual people, organizations, places, or events is purely coincidental. Printed in the USA. ISBN 978-0-9849832-0-9 AUT1003.20120131.431 www.autarch.co CREDITS Lead Designer: Alexander Macris Graphic Design: Carrie Keymel Greg Lincoln Additional Design: Tavis Allison Greg Tito Intern: Chris Newman Development: Alexander Macris Kickstarter Support: Chris Hagerty Tavis Allison Timothy Hutchings Greg Tito Event Support: Tavis Allison Editing: Tshilaba Verite Ryan Browning Jonathan Steinhauer Ezra Claverie Paul Vermeren Chris Hagerty Paul Hughes Art: Ryan Browning -

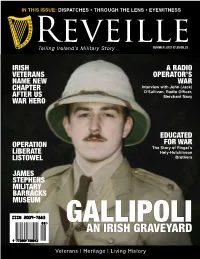

An Irish Graveyard

IN THIS ISSUE: DISPATCHES THROUGH THE LENS EYEWITNESS ReveilleSUMMER 2015 €7.50/£6.25 Telling Ireland’s Military Story IRISH A RADIO VETERANS OPERATOR’S NAME NEW WAR Interview with John (Jack) CHAPTER O‘Sullivan, Radio Officer, AFTER US Merchant Navy WAR HERO EDUCATED FOR WAR OPERATION The Story of Fingal’s LIBERATE Hely-Hutchinson LISTOWEL Brothers JAMES STEPHENS MILITARY BARRACKS 2009788012-08.epsMUSEUM NBW=80 B=20 GALLIPOLIAN IRISH GRAVEYARD Veterans | Heritage | Living History IN THIS ISSUE Editor’s Note Publisher: Reveille Publications Ltd. primary school student from Celbridge PO Box 1078 Maynooth recently educated me on Belgium refugees Co. Kildare who came to my home town during World War I. As a student of history I was somewhat ISSN Print- ISSN 2009-7883 Aembarrassed about having no prior knowledge of this Digital- ISSN 2009-7891 piece of local history. The joy of history is learning more. Editor The Belgian Refugees Committee was established in October 1914 as part of the Wesley Bourke British response to the flow of civilian refugees coming from Belgium. From October [email protected] 1914 Ireland took in Belgian refugees, primarily from Antwerp. The initial effort was Photographic Editor coordinated by an entirely voluntary committee before being taken over by the Local Billy Galligan [email protected] Government Board. An article on the UCD History Hub website details the reception and treatment of the refugees by the Irish committee. The chair of the committee Sub-Editor Colm Delaney was a member of the small pre-war Belgium-Irish community, a Mrs. Helen Fowle. Her connections and ability to speak Flemish was a badly needed asset in dealing Subscriptions with the refugees. -

Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 230 August, 2012 Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD) by Lucas Christopoulos Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. We do, however, strongly recommend that prospective authors consult our style guidelines at www.sino-platonic.org/stylesheet.doc. -

Ancient Greek Artillery Technology

Ancient Greek Artillery Technology from Catapults to the Architronio Canon Michael Lahanas Αρχαία όπλα : καταπέλτες – βαλλίστρες ”Archimedes,” said Lucius, “we know that without your war machinery Syracuse wouldn’t have held out for a month; as it is, we’ve had a rough two years because of them. Don’t think we soldiers don’t appreciate that. They’re superb machines. My congratulations.” Archimedes waved his hand. “Please, they’re nothing really. Ordinary hurling mechanisms—mere toys, that’s all. Scientifically, they have little value. Karel Capek, Apocryphal Tales Bows (the first machine invented by man?) were used at least since 8000 BC according to cave paintings in 'les Dogues' (Castellón, France). Probably bows were invented much earlier (around 20000 BC). The word Catapult comes from the Greek words kata and peltes. (Kata means downward and peltes describes a small shield ). Catapult means therefore shield piercer. Catapults were first invented about 400 BC in the Greek town Syracus under Dionysios I (c. 432-367 BC). The Greek engineers first constructed a comparatively small machine, the gastraphetes (belly-bow), a version of a crossbow. The gastraphetes is a large bow mounted on a case, one end of which rested on the belly of the person using it. When the demands of war required a faster, stronger weapon, the device was enlarged, and a winch pull-back system and base were added. Technology of Catapults (belopoietic from belos (arrow or it is better to say a bolt) and poiw make) was a key part of ancient mechanics, a branch of mathematics that also included fortification building, statics, and pneumatics. -

The Catapult: a History by Tracey E. Rihll Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2007

The Catapult: A History by Tracey E. Rihll Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2007. Pp. xxv + 381. ISBN 978--1--59416-- 035--6.Cloth $29.95 Reviewed by Serafina Cuomo Birkbeck College [email protected] Ancient catapults would appear to be an immensely popular topic. A quick Google search reveals the existence of sites that sell catapult- making kits, and of the alarmingly-named ‘The Hurl’ (‘a worldwide community of catapult enthusiasts pursuing the art, history, science and engineering of hurling’!).1 In contrast, there is relatively little scholarly literature on the subject, and the best recent studies have come out in German or Italian.2 Thus, for years, the main point of reference for English speakers has been the work of E. W. Marsden [1969, 1971]. Now the publication of Tracey Rihll’s book has finally provided an update that is both authoritative and widely accessible. Rihll’s account is organized chronologically. Unlike most ac- counts that focus on the bow as an obvious precursor, she starts the pre-history of the catapult by describing in her first chapter the bow and sling—the rationale for this will emerge later. Chapter 1 sets the tone for the rest of the book in more than one way: Rihll focuses on the older, more ‘primitive’ weapons, because she will argue through- out that newer technologies did not displace older ones. Moreover, the way in which she describes the sling and bow, by paying atten- tion both to the materials used and to actual deployment and effects in a military setting (what could one actually do with a sling? How accurately could one hit a target, and with how much force? How would slingers fit in with their differently-equipped co-fighters?), mir- rors her description of catapults later. -

Macedonian Cavalry

Durham E-Theses The army of Alexander the great English, Stephen How to cite: English, Stephen (2002) The army of Alexander the great, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4162/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The Army of Alexander the Great Stephen English The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Submitted for degree of M.A Department of Classics and Ancient History University of Durham 2002 0 MAY 2003 J2oox( Stephen English The Army of Alexander the Great Submitted for degree of M. A. Department of Classics, University of Durham 2002 Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to be an examination of the army of Alexander the Great, concentrating upon questions of organization and equipment. -

Copyright Frontiergaming 2020 Contents

Sample file COPYRIGHT FRONTIERGAMING 2020 CONTENTS Introduction Page 1 Weapon Profiles Page 13 Setting the Scene Page 2 Weapon List Page 14 Introduction to Gameplay Page 3 Weapon List (Continued) Page 15 Actions Per Turn Page 4 Weapon List (Continued) Page 16 Taking Actions Weapon Creation Page 17 Renown Page 5 Weapon Upgrades Dice Rolls Page 6 Armour, The Defense Rating Page 18 Social Interaction Armour Profiles Page 19 Stealth And The Sneak Skill Armour List Page 20 Attacking From Sneak Page 7 Armour List (Continued) Page 21 Technical Skills Supplies And Equipment Page 22 Looting In-Game Inventory Environmental Investigation Supplies And Equipment List Page 23 Healing And Medicine Page 8 Axioms Page 24 The Healing Chart The Pragmatist Page 25 Combat Page 9 The Gnostic Page 26 Close Combat The Savant Page 27 Thrown Weapons and Objects Aspects Page 28 Dodge, Parry Or Block Sky Traits And Abilities Page 29-30 Damage And Wounding Page 10 Sea Traits And Abilities Page 31-32 Base Wounding Table Land Traits And Abilities Page 33-34 Focused Strikes, Aimed Shots Page 11 Heart Traits And Abilities Page 35-36 AdditionalSample Wounds War Traits And Abilities filePage 37-38 Weaponry Page 12 Underworld Traits, Abilities Page 39-40 Weapons In Gameplay Character Creation Page 41-48 CONTENTS Continued Experience Record Page 48 Storyteller’s Guide Page 51 Wounding Chart Page 49 Creating For Storytellers Page 52 Status Generating Weapons Additional Character Info Generating Armour Character Sheet Page 50 Generating NPCs Page 53 Forged In The Crucible: -

PDF Download Ancient Roman Technology Ebook

ANCIENT ROMAN TECHNOLOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Amelie Von Zumbusch | 24 pages | 15 Jul 2013 | PowerKids Press | 9781477708934 | English | United States BBC - History - Ancient History in depth: Discovering Roman Technology And it was the immunes , a group of highly trained specialists who were specifically employed to maintain the logistical and medical sustenance of the legions. Ranging from doctors, engineers to architects, these men were exempt from the hard labor duties of the rank-and-file soldiers, while also earning more than them — thus hinting at the presumed crucial nature of their jobs. Pertaining to the Roman medical professionals, their dedicated battlefield surgery units were instrumental in the use of innovative contraptions like hemostatic tourniquets and arterial surgical clamps to curb blood loss. Taking all of these factors into account, combined with better diet, the Roman soldiers possibly tended to live longer than their civilian counterparts, thus alluding the efficiency of the ancient Roman doctors and surgeons. While the core ballista mechanism was probably developed by the ancient Greeks by 5th century BC in forms like oxybeles and gastraphetes , there is no doubt that the Romans advanced the practical scope of such fascinating weapon systems, along with their deployment and usage on ancient battlefields. The so-named carroballista was an extension of the similar manuballista technology, but its difference lied in its advantage of maneuverability. In essence, the weapon system was developed as a cart-mounted ballista, thus entailing a type of mobile field artillery. ArcheoArt has described the weapon in some details, based on the reconstruction of Michael Lewis —. The caroballista: a powerful descendent of the Roman ballistae and catapultae. -

The Belly of the Bow Free

FREE THE BELLY OF THE BOW PDF K. J. Parker | 528 pages | 01 May 2003 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781857239607 | English | London, United Kingdom Bow shape - Wikipedia In archerythe shape of the bow is usually taken to be the view from the side. It is the product of the complex relationship of material stressesdesigned by a bowyer. This shape, viewing the limbs, is designed to take into account the construction materials, the performance required, and the intended use of the bow. There are many different kinds of bow shapes. However, most fall into three main categories: straight, recurve and compound. Straight and recurve are considered traditional bows. If a limb is 'straight' its effective length remains the same as the bow is drawn. That is, the string goes directly to the nock in the strung braced position. The materials must withstand these stresses, store the energy, and rapidly give back that energy efficiently. Many bows, especially traditional self bowsare made approximately straight in side-view profile. Longbows as used by English Archers in the Middle Ages at such battles as Crecy and Agincourt were straight limb bows. A recurve bow has tips that curve away from the archer when the bow is strung. The Belly of the Bow definition, the difference between recurve and other bows is that the string touches a section of the limb when the bow is strung. When the limb is recurved tip of limb away from the archerthe string touches the limb before it gets to the nock. The effective length of the limb, as the draw commences, is therefore shorter.