Propensity Score Matched Analysis of Mechanical Vs. Bioprosthetic Valve Replacement in Patients with Previous Stroke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Website : the Bank Website

Website : http://newmaps.twse.com.tw The Bank Website : http://www.landbank.com.tw Time of Publication : July 2018 Spokesman Name: He,Ying-Ming Title: Executive Vice President Tel: (02)2348-3366 E-Mail: [email protected] First Substitute Spokesman Name: Chu,Yu-Feng Title: Executive Vice President Tel: (02) 2348-3686 E-Mail: [email protected] Second Substitute Spokesman Name: Huang,Cheng-Ching Title: Executive Vice President Tel: (02) 2348-3555 E-Mail: [email protected] Address &Tel of the bank’s head office and Branches(please refer to’’ Directory of Head Office and Branches’’) Credit rating agencies Name: Moody’s Investors Service Address: 24/F One Pacific Place 88 Queensway Admiralty, Hong Kong. Tel: (852)3758-1330 Fax: (852)3758-1631 Web Site: http://www.moodys.com Name: Standard & Poor’s Corp. Address: Unit 6901, level 69, International Commerce Centre 1 Austin Road West Kowloon, Hong Kong Tel: (852)2841-1030 Fax: (852)2537-6005 Web Site: http://www.standardandpoors.com Name: Taiwan Ratings Corporation Address: 49F., No7, Sec.5, Xinyi Rd., Xinyi Dist., Taipei City 11049, Taiwan (R.O.C) Tel: (886)2-8722-5800 Fax: (886)2-8722-5879 Web Site: http://www.taiwanratings.com Stock transfer agency Name: Secretariat land bank of Taiwan Co., Ltd. Address: 3F, No.53, Huaining St. Zhongzheng Dist., Taipei City 10046, Taiwan(R,O,C) Tel: (886)2-2348-3456 Fax: (886)2-2375-7023 Web Site: http://www.landbank.com.tw Certified Publick Accountants of financial statements for the past year Name of attesting CPAs: Gau,Wey-Chuan, Mei,Ynan-Chen Name of Accounting Firm: KPMG Addres: 68F., No.7, Sec.5 ,Xinyi Rd., Xinyi Dist., Taipei City 11049, Taiwan (R.O.C) Tel: (886)2-8101-6666 Fax: (886)2-8101-6667 Web Site: http://www.kpmg.com.tw The Bank’s Website: http://www.landbank.com.tw Website: http://newmaps.twse.com.tw The Bank Website: http://www.landbank.com.tw Time of Publication: July 2018 Land Bank of Taiwan Annual Report 2017 Publisher: Land Bank of Taiwan Co., Ltd. -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Relative Timing of Human Migration and Land-Cover and Land-Use Change — An Evaluation of Northern Taiwan from 1990 to 2015 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8t5432st Author Shih, Hsiao-chien Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SAN DIEGO STATE UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The Relative Timing of Human Migration and Land-Cover and Land-Use Change — An Evaluation of Northern Taiwan from 1990 to 2015 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Hsiao-chien Shih Committee in charge: Professor Douglas A. Stow, Chair Professor John R. Weeks Professor Dar A. Roberts Professor Konstadinos G. Goulias June 2020 The dissertation of Hsiao-chien Shih is approved. ____________________________________________ Konstadinos G. Goulias ____________________________________________ Dar A. Roberts ____________________________________________ John R. Weeks ____________________________________________ Douglas A. Stow, Committee Chair May 2020 The Relative Timing of Human Migration and Land-Cover and Land-Use Change — An Evaluation of Northern Taiwan from 1990 to 2015 Copyright © 2020 by Hsiao-chien Shih iii Dedicated to my grandparents, my mother, and Yi-ting. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study was funded by Yin Chin Foundation of U.S.A., STUF United Fund Inc., the Long Jen-Yi Travel fund, William & Vivian Finch Scholarship, and a doctoral stipend through San Diego State University. I would like to thank for the committee members of my dissertation, Drs. Stow, Weeks, Roberts, and Goulias along with other professors. -

12891-017-1768-X

Chen et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2017) 18:410 DOI 10.1186/s12891-017-1768-x RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access The relationship between preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification scores and functional recovery following hip-fracture surgery Li-Huan Chen1,2, Jersey Liang3,4, Min-Chi Chen5, Chi-Chuan Wu6, Huey-Shinn Cheng7, Hsiu-Ho Wang1 and Yea-Ing Lotus Shyu6,8,9,10* Abstract Background: Little is known about the relationship of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification scores (ASA scores) on patient outcomes following hip fracture surgery in Asian countries. Therefore, this study explored the association of patients’ preoperative ASA scores on trajectories of recovery in physical functioning and health outcomes during the first year following postoperative discharge for older adults with hip-fracture surgery in Taiwan. Methods: The data for this study was generated from three prior studies. Participants (N = 226) were older hip-fracture patients from an observational study (n = 86) and two clinical trials (n =61andn = 79). Participants were recruited from the trauma wards of one medical center in northern Taiwan and data was collected prior to discharge and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after hospital discharge. Participants were grouped as ASA class 1–2 (50.5%; ASA Class 1, n =7;ASA Class 2, n = 107) and ASA class 3 (49.5%, n = 112). Measures for mortality, service utilization, activities of daily living (ADL), measured by the Chinese Barthel Index, and health related quality of life, measured by Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36, were assessed for the two groups. -

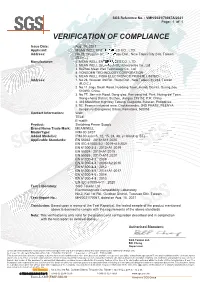

EMC Certificate

SGS Reference No. : VMH/2021/70047A/2021 Page: 1 of 1 VERIFICATION OF COMPLIANCE Issue Date: Aug. 16, 2021 Applicant: MEAN WELL ENTERPRISES CO., LTD. Address: No.28, Wuquan 3rd Rd., Wugu Dist., New Taipei City 248, Taiwan (R.O.C.) Manufacturer: 1. MEAN WELL ENTERPRISES CO., LTD. 2. MEAN WELL (GUANGZHOU) Electronics Co., Ltd 3. SuZhou Mean Well Technology Co., Ltd. 4. YONGDEN TECHNOLOGY CORPORATION 5. MEAN WELL INDIA ELECTRONICS PRIVATE LIMITED Address: 1. No.28, Wuquan 3rd Rd., Wugu Dist., New Taipei City 248, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 2. No.11 Jingu South Road, Huadong Town, Huadu District, Guangzhou 510890, China. 3. No.77, Jian-min Road, Dong-qiao, Pan-yang Ind. Park, Huang-dai Town, Xiang-cheng District, Suzhou, Jiangsu 215152, P.R. China 4. 345 MacArthur HighWay Tabang, Guiguinto, Bulacan, Philippines 5. 9C, Peenya industrial area, Chokkasandra, 2ND PHASE, PEENYA Bengaluru (Bangalore) Urban, Karnataka, 560058 Contact Information: Web: TEL#: E-mail#: Product: Switching Power Supply Brand Name/Trade Mark: MEANWELL Model/Type: IRM-30-24ST Added Model(s): IRM-30-xy(x=5, 12, 15, 24, 48; y= blank or ST) Applicable Standards: EN 55032 : 2015+A11:2020 EN IEC 61000-3-2 : 2019+A1:2021 EN 61000-3-3 : 2013+A1:2019 EN 55024 : 2010+A1:2015 EN 55035 : 2017+A11:2020 EN 61000-4-2 : 2009 EN 61000-4-3 : 2006+A2:2010 EN 61000-4-4 : 2012 EN 61000-4-5 : 2014+A1:2017 EN 61000-4-6 : 2014 EN 61000-4-8 : 2010 EN IEC 61000-4-11 : 2020 Test Laboratory: SGS Taiwan Ltd. -

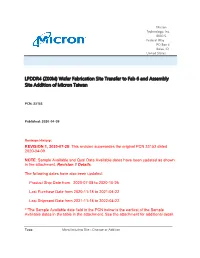

LPDDR4 (Z00M) Wafer Fabrication Site Transfer to Fab 6 and Assembly Site Addition of Micron Taiwan

Micron Technology, Inc. 8000 S. Federal Way PO Box 6 Boise, ID United States LPDDR4 (Z00M) Wafer Fabrication Site Transfer to Fab 6 and Assembly Site Addition of Micron Taiwan PCN: 33153 Published: 2020-04-09 Revision History: REVISION 1, 2020-07-28: This revision supersedes the original PCN 33153 dated 2020-04-09. NOTE: Sample Available and Qual Data Available dates have been updated as shown in the attachment, Revision 1 Details. The following dates have also been updated: Product Ship Date from 2020-07-08 to 2020-10-26 Last Purchase Date from 2020-11-18 to 2021-04-22 Last Shipment Date from 2021-11-18 to 2022-04-22. **The Sample Available date field in the PCN below is the earliest of the Sample Available dates in the table in the attachment. See the attachment for additional detail. Type: Manufacturing Site - Change or Addition Description: LPDDR4 (Z00M) wafer fabrication will transfer to Micron’s Fab 6 site with sample availability according to the listed package type and temperature grade below. An additional assembly site, Micron Taiwan, will be added during this fabrication site change. Samples will be made available with Fab 6 Z00M using both PTI Taiwan and Micron Taiwan assembly sites. Current Sites: Micron Technology Taiwan, Inc (Fab 11), 667, Fuhsing 3rd Rd Hwa-Ya Technology Park, Guishan District, Taoyuan, Taiwan Powertech Technology Inc, No.10, Datong Rd; Hsinchu Industrial Park; Hukou; Hsinchu, 30352; Taiwan Advanced Semiconductor Engineering Inc, 26 Chin 3rd Road, Kaohsiung, Taiwan New Sites: Micron Technology, Inc. (Fab 6), 9600 Godwin Dr, Manassas, Virginia Micron Memory Taiwan Co, Ltd., No.88 Houke South Road, Houli District, Central Taiwan Science Park, Taichung City, Taiwan R.O.C. -

Quinolone and Organophosphorus Insecticide Residues in Bivalves and Their Associated Risks in Taiwan

molecules Article Quinolone and Organophosphorus Insecticide Residues in Bivalves and Their Associated Risks in Taiwan 1, 2, 1 3 4 Ching-Feng Wu y , Ching-Hung Chen y, Ching-Yang Wu , Chen-Si Lin , Yao-Chi Su , Ching-Fen Wu 4, Hsiao-Pei Tsai 5,6, Pei-Shan Fan 4, Chang-Hui Yeh 4, Wei-Cheng Yang 3,* and Geng-Ruei Chang 4,5,6,* 1 Division of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Department of Surgery, Chang Gung University, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, 5 Fuxing Street., Guishan District, Taoyuan 33305, Taiwan; [email protected] (C.-F.W.); [email protected] (C.-Y.W.) 2 Department of Anesthesiology, Show Chwan Memorial Hospital, 1 Section, 542 Chung-Shan Road, Changhua 50008, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 Department of Veterinary Medicine, School of Veterinary Medicine, National Taiwan University, 4 Section. 1 Roosevelt Road, Taipei 10617, Taiwan; [email protected] 4 Department of Veterinary Medicine, National Chiayi University, 580 Xinmin Road, Chiayi 60054, Taiwan; [email protected] (Y.-C.S.); [email protected] (C.-F.W.); [email protected] (P.-S.F.); [email protected] (C.-H.Y.) 5 College of Veterinary Medicine, Veterinary Teaching Hospital, National Chiayi University, 580 Xinmin Road, Chiayi 60054, Taiwan; [email protected] 6 Ph.D. Program of Agriculture Science, National Chiayi University, 300 Syuefu Road, Chiayi 60004, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] (W.-C.Y.); [email protected] (G.-R.C.); Tel.: +886-2-33663871 (W.-C.Y.); +886-5-2732946 (G.-R.C.) These authors contributed equally to this work. -

2021.08.05.21261532V1.Full.Pdf

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.05.21261532; this version posted August 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . 1 Title Page 2 Safety and Immunogenicity of CpG 1018 and Aluminium Hydroxide-Adjuvanted 3 SARS-CoV-2 S-2P Protein Vaccine MVC-COV1901: A Large-Scale Double-Blind, 4 Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Trial 5 6 Hsieh Szu-Min, M.D.1, Ming-Che Liu, M.D.,2,3, Yen-Hsu Chen, M.D.,4,5, Wen-Sen Lee, 7 M.D.6,7, Shinn-Jang Hwang, Prof8, Shu-Hsing Cheng, M.D.,9,10, Wen-Chien Ko, Prof.11,12, 8 Kao-Pin Hwang, M.D.13, Ning-Chi Wang, M.D.14, Yu-Lin Lee, M.D.15,16, Yi-Ling Lin, 9 Ph.D.17,18, Shin-Ru Shih, Ph.D.19, ChungGuei Huang, Ph.D.19,20, Chun-Che Liao, Ph.D.17, 10 Jian-Jong Liang, Ph.D.17, Chih-Shin Chang, PhD.18, Charles Chen, adj. Prof.21,22, Chia En 11 Lien, M.D.21,23, I-Chen Tai, M.D.*21, Tzou-Yien Lin, Prof.*24,25 12 13 1. Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan 14 University Hospital and College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan 15 (R.O.C.) 16 2. Clinical Research Centre, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan (R.O.C.) 17 3. -

SCOPE CERTIFICATE Scope Certificate Number: 20-317993

IDFL LABORATORY AND INSTITUTE SCOPE CERTIFICATE Scope Certificate Number: 20-317993 IDFL declares that ZIG SHENG INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. LICENSE NUMBER 007426 No. 60, Dongwanshou Rd., Guishan District Taoyuan City, Taiwan 333025 Taiwan has been inspected and assessed according to the Global Recycled Standard (GRS) - Version 4.0 - and that products of the categories as mentioned below (and further specified in the appendix) conform with this standard. Product Categories: Processed Materials (PC0035), Dyed Yarns (PC0029), Greige Yarns (PC0030) Processing steps / activities carried out under the responsibility of the above-mentioned company for the certified products: Texturing(PR0027) , Spinning(PR0027) , Trading(PR0030) , Compounding(PR0034) This Certificate is valid until: 16 Apr. 2022 Place and Date of Issue Stamp of Issuing Body Taipei, 16 Apr. 2021 IDFL License No: GRS-IDFL-19 Wilford Lieber, CEO IDFL Laboratory and Institute 4F. No. 163 Wun Hua Rd. Sec. 2 Banqiao District, New Taipei City This Certificate of Compliance provides no proof that any goods delivered by its holder are Global Recycled Standard (GRS) certified. Proof of Global Recycled Standard (GRS) certification of goods delivered is provided by a valid Transaction Certificate (TC) covering them. The issuing body can withdraw this certificate before it expires if the declared compliance is no longer guaranteed. This electronically issued document is the valid original version. Scan QR Code to verify certificate. Appendix to Certificate No.: 20-317993 ZIG SHENG INDUSTRIAL CO., -

Reconstructing Foveola by Foveolar Internal Limiting Membrane Non

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Reconstructing Foveola by Foveolar Internal Limiting Membrane Non- Peeling and Tissue Repositioning for Lamellar Hole-Related Epiretinal Proliferation Tzyy-Chang Ho1*, Allen Yi-Lun Ho4 & Muh-Shy Chen1,2,3 Diferences in the pathogenesis and clinical characteristics between lamellar macular hole (LMH) with and without LMH-associated epiretinal proliferation (LHEP) can have surgical implications. This study investigated the efects of treating LHEP by foveolar internal limiting membrane (ILM) non-peeling and epiretinal proliferative (EP) tissue repositioning on visual acuity and foveolar architecture. Consecutive patients with LHEP treated at our institution were enrolled. The eyes were divided into a conventional total ILM peeling group (group 1, n = 11) and a foveolar ILM non-peeling group (group 2, n = 22). In group 2, a doughnut-shaped ILM was peeled, leaving a 400-μm-diameter ILM without elevated margin over the foveola after EP tissue repositioning. The EP tissue was elevated, trimmed, and inverted into the LMH. Postoperatively, the LMH was sealed in all eyes in group 2, with signifcantly better best- corrected visual acuity (−0.26 vs −0.10 logMAR; p = 0.002). A smaller retinal defect (p = 0.003), a more restored ellipsoid zone (p = 0.002), and a more smooth foveal depression (p < 0.001) were achieved in group 2. Foveolar ILM non-peeling and EP tissue repositioning sealed the LMH, released the tangential traction, and achieved better visual acuity. The presumed foveolar architecture may be reconstructed surgically. LMH with LHEP could have a combined degenerative and tractional mechanism. Pang et al.1 classifed lamellar macular hole (LMH) into two types according to the fndings on optical coherence tomography (OCT) as (1) associated with a high refectivity epiretinal membrane (ERM) compared with the surface of the retina and (2) lamellar hole-associated epiretinal proliferation (LHEP) of homogenous medium refectivity. -

TAIWAN Capital Markets Q3 2020

M A R K E T B E AT TAIWAN Capital Markets Q3 2020 YoY Investment Market Surged in Q3, With TSMC Expanding in Tainan Science Park Chg Investment in Q3 totaled NT$71.2 billion, up 406.9% q-o-q and up 242.4% on the same quarter last year. Investment volume for the Q1 to Q3 2020 period has now exceeded the full year total volume for 2019. Transactions were concentrated in Taipei City, Taoyuan City and Tainan City, together 98.7B +137% accounting for 76.6% of the total investment volume in Q3. YTD Investment Volume (NTD) Local buyers dominated the market in the quarter, with the biggest deal in Q3, and for the year to date, being Fubon Life Insurance’s acquisition of the Sunworld Dynasty Hotel for NT$25.5 billion. TSMC continued preparations for operational expansion in the quarter, acquiring three factories at 71.2B +242% Q3 Investment Volume (NTD) Tainan Science Park for NT$9.4 billion, adding to their Q2 acquisition, for a total investment of more than NT$10 billion. 49 +81% Investment Buyers Target Industrial Offices and Warehouses Q3 Deals Owner occupier buyers remained the primary market purchasers in Q3, although investment buyers targeted a variety of real estate sectors in the quarter. Notable deals included Fubon Life Insurance‘s acquisition of the Sunworld Dynasty Hotel for NT$25.5 billion, while Genyi Construction took Sampo’s previous warehouse in Guishan District, Taoyuan, for NT$1.8 billion; and Chunghwa Post and Fengshin Steel separately acquired ownership shares in Farglory U-Town for NT$389 million and NT$327 million respectively. -

Danggui Buxue Tang Inhibits 2, 4-Dinitrochlorobenzene: Induced

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2015, Article ID 672891, 10 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/672891 Research Article Danggui Buxue Tang Inhibits 2,4-Dinitrochlorobenzene: Induced Atopic Dermatitis in Mice Li-Wen Fang,1 Chao-Chun Cheng,2,3 Tzann-Shun Hwang,4 Wen-Chung Huang,5,6 Chian-Jiun Liou,7 Wen-Chyuan Chen,8 and Shu-Ju Wu2,6 1 Department of Nutrition, I-Shou University, Yanchao District, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan 2Department of Nutrition and Health Sciences, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Guishan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan 3Nutritional Science Department, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, Taiwan 4Graduate Institute of Biotechnology, Chinese Culture University, Yang-Ming-Shan, Taipei, Taiwan 5Graduate Institute of Health Industry Technology, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Guishan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan 6Research Center for Industry of Human Ecology, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Guishan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan 7Department of Nursing, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Guishan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan 8Center for General Education, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Guishan District, Taoyuan City, Taiwan Correspondence should be addressed to Shu-Ju Wu; [email protected] Received 1 January 2015; Accepted 19 February 2015 Academic Editor: Xiu-Min Li Copyright © 2015 Li-Wen Fang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Danggui Buxue Tang (DBT) is a herbal decoction that has been used in Chinese medicine to enhance qi and blood circulation. -

Sigma's 30Th International Nursing Research

Sigma's 30th International Nursing Research Congress Effects of Elderly Simulated Experience Course on Knowledge, Attitude, and Willingness of Care in Clinical Teachers Shu Hua Kao V, MSN1 Tzu-Hsin Huang, MSN2 Kuei Ru Chou, Professor, PhD, RN3 Jeng Wang, PhD4 Yun Fan Yang, BN1 Su In Hsieh5 Yun Fan Chou, MSN1 (1)Nursing Department, Taoyuan Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan, Taiwan (2)Nursing Department, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Taoyuan, Taiwan, Taoyuan City, Taiwan (3)College of Nursing, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan (4)Department of Geriatric Care and Management, Chang-Gung University of Science & Technology, Tao-Yau, Taiwan (5)Department of Geriatric Care and Management, Chang-Gung University of Science & Technology, Tao-Yau,, Department of Geriatric Care and Management, Chang-Gung University of Science & Technology, Tao-Yau,, Taiwan, Taiwan Purpose: 1. To understand the current situation of nursing teachers' aging knowledge, attitudes and willingness to care for the elderly.2. To explore the differences in the knowledge, attitudes and willingness to care for the elderly before and after the intervention of the Elderly Simulated Experience Program. Methods: In this study, the pre-experimental study was carried out. The experimental group was involved in the intervention program of the Elderly Simulated Experience Course. To facilitate the sampling of a district from Taoyuan City Hospital Nursing Department of clinical nursing teachers. The "Aging Knowledge of the Elderly", "Assessment of the Elderly Personality", "Care for the Elderly", before and after the course of the course, and the sixth week after the intervention. Simulate Experience Course Satisfaction "and" Reflection History ". During the case: from September 1, 2017 to November 30, 2017, there were 42 experimental groups and 54 control groups.