IWMI-Tata Partners' Meet Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portrait of Population Gujarat

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 A PORTRAIT . 01" POPULATION GUJARAT OIRf:CTORA IE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS GUJARAT, AHMADABAD 67' 61' 72' ~ ________~N~' ________~7r5' __, BOUNOAilIES: INT£RNAT~NAL""." ... STATE/UNIONTERRITORY GUJARAT ~STR~L .... TALUKA .. ... 25' 21' ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS 1991 A Kms,Q 30 60 90 I2OKms, ~1iIIi H=+ I I I 24' 23' ,,, .APITIl tOISTRICTllElDQUARTERI rnu OTAlUKAHEAOQUARTERl IDAMAN! DIU) WH~REYER THE NAME OF ADISTRICT / rAlU~A DIFFERS fRe'ITSHEiOQUARTERI TOWN NA'E, THE FORMER APPEARS \IIlfHIN BRAl:~E'5, ~!, Alil'i~ rr~E OANGS), RIt.JPIPlA INANDOOI ~ __~~ ______L___ ____ ~ ____ -L__ _____J ________ J_ ____ ~_J __"---- __~------~~ 67'[~'oIGreetlwlcn 68' 61' 70' II' 11' 73' 74' CONTENTS PAGE FOREWORD XV PREFACE XVII A<.XNOWLEDGEMEl' rs XIX FJGUR.Es AT A GLANCE. XXI CHMTERI I INntODUcnON 1 n HOW MANY ARE WE? 15 m VILLAG~ DWELLERS AND TOWN DWELLERS 101 IV ARE THE NUMBER OF MEN AND WOMEN BALANCED? 147 V HOW MANY OF US CAN. READ AND WRITE ? 178 VI lANGUAGES WE SPEAK 219 VB REUGION WE FOLLOW 237 vm SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES 263 IX HOW MANYOF US WORK? 290 X FEknLfIY LEVELS AND TRENDS 317 XI MOVEMENT OF PEOPLE 346 XU SUMMARY 366 LIST OF STATEMENTS Statement Cllapter II Page II. 1 Grouping of districts by population size in 19 ranges descending order 11.2 The area and Population of all States and Union 23 Territories and their percentage to total national area and population II. 3 Distribution of talukas of Kacbcbb district by 28 population size ranges 11.4 Distribution of talukas of Janmagar district by 30 population size ranges II. -

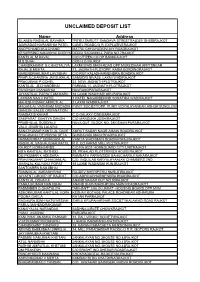

Unclaimed Deposit List

UNCLAIMED DEPOSIT LIST Name Address SILABEN RASIKLAL BAVARIA "PITRU SMRUTI" SANGAVA STREETRAJDEV SHERIRAJKOT JAMNADAS NARANBHAI PATEL CANEL ROADC/O R. EXPLASIVERAJKOT ANOPCHAND MULCHAND MATRU CHHAYADIGVIJAY ROADRAJKOT KESARISING NANJIBHAI DODIYA DODIA SADANMILL PARA NO.7RAJKOT KANTILAL M RAVAL C/O CITIZEN CO.OP.BANKRAJKOT M S SHAH CCB.H.O.RAJKOT CHANDRAKANT G CHHOTALIYA LAXMI WADI MAIN ROAD OPP MURLIDHAR APPTSNEAR RAJAL B MEHTA 13, JAGNATH PLOTOPP. KADIA BORDINGRAJKOT NARENDRAKUMAR LAVJIBHAI C/O RUP KALADHARMENDRA ROADRAJKOT PRAFULCHANDRA JAYSUKHLAL SAMUDRI NIVAS5, LAXMI WADIRAJKOT PRAGJIBHAI P GOHEL 22. NEW JAGNATH PLOTRAJKOT KANTILAL JECHANDBHAI PARIMAL11, JAGNATH PLOTRAJKOT RAYDHAN CHANABHAI NAVRANGPARARAJKOT JAYANTILAL PARSOTAM MARU 18 LAXMI WADIHARI KRUPARAJKOT LAXMAN NAGJI PATEL 1 PATEL NAGARBEHIND SORATHIA WADIRAJKOT MAHESHKUMAR AMRUTLAL 2 LAXMI WADIRAJKOT MAGANLAL VASHRAM MODASIA PUNIT SOCIETYOPP. PUNIT VIDYALAYANEAR ASHOK BUNGLOW GANESH SALES ORGANATION RAMDAS B KAHAR C.O GALAXY CINEMARAJKOT SAMPARAT SAHITYA SANGH C/O MANSUKH JOSHIRAJKOT PRABHULAL BUDDHAJI NAVA QUT. BLOCK NO. 28KISHAN PARARAJKOT VALJI JIVABHIA LALKIYA SANATKUMAR KANTILAL DAVE AMRUT SADAR NAGR AMAIN ROADRAJKOT BHAGWANJI DEVSIBHAI SETA GUNDAVADI MAIN ROADRAJKOT HASMUKHRAY CHHAGANLAL VANIYA WADI MAIN ROADNATRAJRAJKOT RASIKLAL VAGHAJIBHAI PATEL R.K. CO.KAPAD MILL PLOTRAJKOT RAJKOT HOMEGARDS C/O RAJKOT HOMEGUARD CITY UNITRAJKOT NITA KANTILAL RATHOD 29, PRHALAD PLOTTRIVEDI HOUSERAJKOT DILIPKUMAR K ADESARA RAMNATH PARAINSIDE BAHUCHARAJI NAKARAJKOT PRAVINKUMAR CHHAGANLAL -

2010-2011 Printing.Pmd

Ace Software Exports Ltd. CORPORATE INFORMATION Board of Directors: Vikram B. Sanghani Joint Managing Director Sanjay H. Dhamsania Joint Managing Director Dharmsibhai R. Vadaliya Independent Director Vimal L. Kalaria Independent Director Pratik C. Dadhania Independent Director Company Secretary: N. I. Thomas Secretarial Consultants M/s. MJP Associates, Practising Company Secretaries Rajkot Statutory Auditors: M/s. Kalaria & Sampat, Chartered Accountants, Rajkot Bankers Bank of Baroda HDFC Bank Ltd. Axis Bank Ltd. Registered Office: 801 – Everest Commercial Complex, Opp. Shashtri Maidan, Rajkot – 360 001, Gujarat, India 22 Ace Software Exports Ltd. NOTICE Notes: 1. A member entitle to attend and vote at the meeting is entitled to Notice is hereby given that the Seventeenth Annual General Meeting appoint a proxy to attend and vote instead of himself and such of the Members of Ace Software Exports Limited will be held on proxy need not be a member of the company. The proxies to be th Thursday, 29 September, 2011 at 11:00 am at the Regd. Office of effective should be deposited at the registered office of the the Company situated at 801, Everest Commercial Complex, Opp. company not later than 48 hours before the commencement of Shastri Maidan, Rajkot – 360 001, Gujarat, India to transact the the meeting. following businesses: 2. Corporate Members intending to send their authorized representative to attend the Meeting are requested to send a Ordinary Business: certified true copy of the Board Resolution authorizing their 1. To received, consider and adopt the Audited Balance Sheet as representative to attend and vote on their behalf at the meeting. -

The SSR Based Linkage Map Construction and Identification of Qtls for Blast (Pyricularia Grisea) Resistance in Pearl Millet (Pen

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; 7(2): 3057-3064 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2018; 7(2): 3057-3064 The SSR based linkage map construction and Received: 12-01-2018 Accepted: 14-02-2018 identification of QTLs for blast (Pyricularia grisea) resistance in pearl millet (Pennisetum Sanghani Jayeshkumar Maganlal Department of Biotechnology, glaucum (l.) r. br.) Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh, Gujarat, India AO Sanghani Sanghani Jayeshkumar Maganlal, AO Sanghani, VV Kothari, SS Raval, Department of Biotechnology, JH Kahodariya, HR Ramani, KJ Vadher, HP Gajera, BA Golakiya and Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh, Gujarat, India MK Mandavia VV Kothari Abstract Department of Biotechnology, Blast of pearl millet is one of the most important devastating diseases limiting pearl millet productivity. Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh, Gujarat, India The DNA-based marker tools facilitate better understanding of the inheritance and expression of blast. To fulfill the objectives, two pearl millet inbred parental lines viz. J – 2537 x ICMB - 95444 were SS Raval crossed to produce F1 and the F1 progenies were selfed to produce mapping population comprising of 36 Department of Biotechnology, segregating F2 progenies for generating marker data using 55 SSR out of 100 markers exhibiting clear Junagadh Agricultural University, polymorphism between parental lines. The blast screening of segregating F2 population progenies against Junagadh, Gujarat, India Blast was done at JAU, Jamnagar. R-QTL interval mapping -

The SSR Based Linkage Map Construction and Identification of Qtls for Blast (Pyricularia Grisea) Resistance in Pearl Millet (Pen

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2018; 7(2): 3057-3064 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2018; 7(2): 3057-3064 The SSR based linkage map construction and Received: 12-01-2018 Accepted: 14-02-2018 identification of QTLs for blast (Pyricularia grisea) resistance in pearl millet (Pennisetum JM Sanghani Department of Biotechnology, glaucum (l.) r. br.) Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh, Gujarat, India AO Sanghani JM Sanghani, AO Sanghani, VV Kothari, SS Raval, JH Kahodariya, HR Department of Biotechnology, Junagadh Agricultural University, Ramani, KJ Vadher, HP Gajera, BA Golakiya and MK Mandavia Junagadh, Gujarat, India Abstract VV Kothari Blast of pearl millet is one of the most important devastating diseases limiting pearl millet productivity. Department of Biotechnology, Junagadh Agricultural University, The DNA-based marker tools facilitate better understanding of the inheritance and expression of blast. Junagadh, Gujarat, India To fulfill the objectives, two pearl millet inbred parental lines viz. J – 2537 x ICMB - 95444 were crossed to produce F1 and the F1 progenies were selfed to produce mapping population comprising of 36 SS Raval segregating F2 progenies for generating marker data using 55 SSR out of 100 markers exhibiting clear Department of Biotechnology, polymorphism between parental lines. The blast screening of segregating F2 population progenies against Junagadh Agricultural University, Blast was done at JAU, Jamnagar. Junagadh, Gujarat, India R-QTL interval mapping method identified two blast QTLs on Linkage Group 1 and Linkage Group 6. JH Kahodariya This best single-QTL model detected by interval mapping on Linkage Group 1 (BRP11 marker) recorded Department of Biotechnology, a high LOD score of 8.2 and explained 46.4% phenotypic variation with map position 15.8 Linkage Junagadh Agricultural University, Group 6 (BRP37 marker) recorded a high LOD score of 1.6 and explained 36% phenotypic variation in Junagadh, Gujarat, India blast incidence among 36 F2 progenies against Pyricularia grisea pathogen. -

(CA) Satadhar Complex, Opp. Govt. Ayurvedic Hospital, Amreli

A D Ruparel Abhabhai G. Parmar Abhabhai P. Katara C/o. A. D. Rupar el & Compani New Varchraj Hotel, "Chamunda Krupa", (CA) 402, Ship apartment, Near Soni Bording, Satadhar Complex, opp. Welcome School, Girnar Darvaja, Opp. Govt. Ayurvedic Hospital, Junagadh Junagadh Amreli 9426719000 9825235273 Abhi Jain Adarsh Desai Adhyashakben A. Majmudar E-21, Akash tower, 11, Gujarat Indus trial Estate, Mayor shree (JMC), Nr Judges bunglow road, Nr. PVR Cinema, "SAMRAN" B/h. Con vent School, Bodakdev, Old chhani road Near Samir Apartment, Ahmedabad-380054 Vadodara Gandhigram 9978445229 9824453033 Junagadh Adremanbhai A. Panja Aab Shaikh / Y. N. Pandya Ajay Karkar Fruit Bazar, Mo Vegetable Narendra Mitra Makbul Shah Noble Office Market Chember 1st Floor, Nagar Road Junagadh Junagadh Kalva Chowk, 9687824151 9427242828 Junagadh 9824211858 Ajaybhai Chotai Ajaybhai Kalavadiya Ajaybhai Makadiya Nilgagan Appartmen t, Block No. 24, Rajkot Rajkot Talav Darvaja, Junagadh 9824450007 Ajaybhai Rupareliya Ajitbhai / Bharatbhai Vank Alkeshbhai F. Gundaniya Shrinathji krupa, Raviraj Group, Block No.102, B-14, Niltarang Society, Near Bus Jitendra park, Parijat Palace, Shrinath Nagar , Stand, Zanzardaroad Giriraj Main Road Junagadh Junagadh Junagadh 9925625570 9909037437 9825771581 Alpaben Unadkat Alpeshbhai Chavda Alpeshbhai Jarsaniya Sharuat Dainik, Akhbar Bhavan, Water Works Engineer , JMC 102, Dwarika Planum, Girnar Road, 37, Meera Nagar, Shashikunj Noble Estate-A, Near Ekla vya Junagadh Road School, Zanzarda Road 9825220771 Junag adh Junagadh 9426027921 9426268166 -

Unicorn Organics Limited

SANSCO SERVICES - Annual Reports Library Services - www.sansco.net UNICORN ORGANICS LIMITED UNICORN ORGANICS FOURTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT 1998 www.reportjunction.com SANSCO SERVICES - Annual Reports Library Services - www.sansco.net UNICORN ORGANICS LIMITED BOARD OF DIRECTORS ShriY.V.Pai, I.A.S. (Retd.,) Chairman (Nominee) Shri Bhanu C. Sanghani, Director Shri Bharat P. Raut, Director Shri D. Seetharamaiah, Director (Nominee) Shri Dwirek K. Raj, Director Shri G.V.S. Ramesh, Director (Nominee) upto 13.07.99 Shri Ramesh V. Shah, Director Shri Sanjay B. Sanghani, Director Shri Vinod A. Sanghani, Director upto 19.2.99 Shri Atul B. Sanghani, Managing Director ASST, COMPANY SECRETARY T.N. Kannan B.Com., A.C.S. AUDITORS Nataraja lyer& Co., Chartered Accountants 1-10-126, Ashoknagar, Hyderabad - 500 020 BANKERS State Bank of India Commercial Branch, Secunderabad - 500 003. FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS The Industrial Credit & Investment Corporation of India Ltd. Industrial Development Bank of India The Industrial Finance Corporation of India Ltd. Andhra Pradesh Industrial Development Corporation Ltd. LISTED WITH The Hyderabad Stock Exchange Ltd. The Stock Exchange, Mumbai The Stock Exchange, Ahmedabad REGISTRARS & SHARE TRANSFER AGENTS Karvy Consultants Limited 21, Avenue 4, Street No. 1, CONTENTS Banjara Hills, Notice of Meeting 2-3 Hyderabad - 500 034 Directors' Report 4-7 / REGISTERED OFFICE Auditors' Report 8-9 ^ 13/1, Rasulpura Balance Sheet 10 -AP.B. No. 2112 ^Secunderabad - 500 003 Profit & Loss Account 11 Schedule to Accounts 12-20 f PLANT Balance Sheet Abstract 21 804, Waddepally Village Warangal District Cash Flow Statement 22 Andhra Pradesh www.reportjunction.com SANSCO SERVICES - Annual Reports Library Services - www.sansco.net UNICORN ORGANICS LIMITED NOTICE SPECIAL BUSINESS: Notice is hereby given that the Fourteenth Annual 5) To consider and if thought fit, to pass with or General Meeting of the Members of the Company without modification, the following resolution as will be held on Thursday, the 30th September, 1999 an Ordinary Resolution. -

Noble Ayurved College & Research Institute

NOBLE AYURVED COLLEGE & RESEARCH INSTITUTE - JUNAGADH (GUJARAT) Details of Students Admitted in Under Graduate Course for the Year 2017 - 2018 Category Sr. No. Name of Student Father's Name Date of Birth Fee Receipt Number and Date Residential Address Govt./Management Quota % of PCB in + 10+2 (Gen./SC/ST/OBC/ Other) Opp. Narshinh School Street, Nr. 1 Ansari Mushkanbanu Gafar Gafar 11/10/1999 14592 & 25-05-2018 GQ 76.88% OBC Mullawada Kaman, Junagadh 2 Beriya Mansi Pravinbhai Pravinbhai 07/06/2000 14682 & 03-07-2018 Opp. Bus Stand, 'Gokul Dairy', Upleta GQ 85.78% OBC H-404, copper recidency, gondal road, 3 Bhalani Happy Kiritbhai Kiritbhai 30/07/2000 14632 & 07-06-2018 MQ 8045.00% General rajkot "Shivalay" 93, ambani park dabhar road 4 Bhammar Jil Desurbhai Desurbhai 30/3/2000 14668 & 26-06-2018 GQ 72.00% OBC veraval gir somnath 5 Bhatti Ridhdhiben Dipakbhai Dipakbhai 05/12/1999 14637 & 08-06-2018 vanthali, vanthali,junagadh MQ 66.22% OBC triveni nagar madhuram timbavadi 6 Bhatti Saraben Hiteshbhai Hiteshbhai 15/08/2000 14735 & 05-07-2018 GQ 65.11% OBC junagadh Shyamnagar 'D' block, near law college, 7 Bheda Kasti Nimeshbhai Nimeshbhai 04/06/00 14595 & 26-05-2018 GQ 87.55% General 80 feet road, wadhwan city, 8 Chandera Drashti Ramsibhai Ramsibhai 25/07/2000 13566 & 06-03-2018 morvad, kodinar, gir somnath GQ 57.66% OBC 9 Chavda Vanraj Babubhai Babubhai 15/04/2000 Freesheep no. 418 & 21-09-2017 Vadala,Maliya(hatina), Junagadh. GQ 81.77% SC Pipaliya nagar,k.d.street,mangrol 10 Chovatiya Riddhiben Rajeshkumar Rajeshkumar 23/03/2000 14589 & 23-05-2018 GQ 87.50% General road,keshod ,junagadh. -

Spring 2017 Commencement Program

146TH YEAR OF THE UNIVERSITY MAY 11-14 SPRING 2017 VIRGINIA POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE AND STATE UNIVERSITY 1 COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY DIGNITARIES AND INVITED SPEAKERS Timothy D. Sands, President, Virginia Tech Tyler O. Walters, Dean of University Libraries Sheryl Sandberg, Chief Operating Officer of Facebook and Founder of Muhammad R. Hajj, Associate Dean of the Graduate School LeanIn.org, Keynote Speaker, University Commencement Amy Pruden, Associate Dean of the Graduate School, and Director, Laura Lindenfeld, Director, Alan Alda Center for Communicating Interdisciplinary Graduate Education Science and Professor, School of Journalism, Stony Brook Kenneth H. Wong, Associate Dean of the Graduate School in the University, Keynote Speaker, Graduate School Commencement National Capital Region and Director of the Northern Virginia Mehul P. Sanghani, President and Chief Executive Officer, Octo Center, Introduction of the National Capital Region Faculty Consulting Group Inc., Class of 1998, Keynote Speaker, Association Speaker National Capital Region Commencement Montasir Abbas, President of the Faculty Senate, Message from the Regina E. Dugan, Vice President of Engineering, Building 8, Faculty and Commencement Marshal, Graduate School and Facebook, Classes of 1984 and 1985, Special Remarks, University Commencements University Commencement Rebecca Oswalt, Female Member-At-Large, Class of 2017, Opening John R. Lawson II, President and Chief Executive Officer of W.M. Reflections, University Commencement Jordan Company, Class of 1975, William H. Ruffner Medal Award Patrick M. Finn, President, Class of 2017, Message from the Class Recipient President, University Commencement Letitia A. Long, Chairman of the Board, Intelligence and National Allison L. Crandell, Vice President, Class of 2017, Closing Reflections, Security Alliance, Class of 1982, University Distinguished University Commencement Achievement Award Recipient Alexa Parsley, President, Student Government Association, Class of Nancy M. -

Why Did Narendra Modi Win? Investigating Whether Religious Nationalist Sentiment Was Responsible for One of the Most Significant Power Shifts in Indian History

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Student Theses Baruch College 1-1-2015 Why Did Narendra Modi Win? Investigating whether religious nationalist sentiment was responsible for one of the most significant power shifts in Indian history Abhinaya Swaminathan Baruch College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/bb_etds/59 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Acknowledgement……………………………………………………………………………………………… ii 2. Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. iii 3. List of Abbreviations and Key Terms…………………………………………………………………... iv 4. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 a. The Puzzle – Modi’s controversial rise to power…………………………………………………..…………. 3 b. The Argument – How Modi won despite, not because of, his Hindu Nationalist past..…..………….. 5 c. The Research – Literature Review and Methodology…………………………………………………………… 7 5. Incumbent Government’s Failures ………………………………………………………………….…. 11 a. Historical Context – Origins of the current coalition government…….…………………………………..……. 11 b. Policy Paralysis – UPA government’s failure to pass significant legislative measures……………….. 15 c. Impact on Modi’s Campaign – Support of the middle class and the private sector……………………………………..... 20 6. Modi’s Rise to Leadership……………………………………………………………………………......... 24 a. Historical Context Why the BJP brand had to be reshaped……………………………………………………... 24 b. Split from the old order – Discord within the leadership and the breaking of old ties…………………………. 28 c. Modi’s leadership of a new BJP – The right man for the party and the country……………………………………………. 32 7. Modi’s Campaign Strategy a. A presidential-style campaign – A contest of personalities, not parties……………………………………………………… 34 b. -

Rajkot-District-Profile.Pdf

Rajkot 1 Index 1 Rajkot: A Snapshot 2 Economy and Industry Profile 3 Industrial Locations/ Infrastructure 4 Support Infrastructure 5 Social Infrastructure 6 Tourism 7 Investment Opportunities 2 1 Rajkot : A Snapshot 3 Introduction: Rajkot § Rajkot is located in the south-west region of Gujarat Map 1: District Map of Rajkot with talukas § The district headquarter is Rajkot city –Largest city in Saurashtra and fourth largest in Gujarat state § The district has 14 talukas of which the major talukas are Rajkot, Morbi, Jetpur, Wankaner, Upleta and Dhoraji § Rajkot city is considered the economic, industrial and educational hub of the region § The district boasts of a stock exchange, which is linked with exchanges in Mumbai, Kolkata & New Delhi Maliya Morbi § Engineering and Auto ancillary industry is viewed as the growth engine of the district .Textiles and Apparels is also an Tankara emerging sector Wankaner Paddhari § Ajanta, world’s largest clock manufacturer is present in the Rajkot Lodhika district Jasdan Jam Kandorna Kotda Gondal § Focus sectors Upleta Sanghani § Engineering & electronics Dhoraji Jetpur § Textiles & apparels § Chemicals District Headquarter § Infrastructure Talukas Source : Rajkot District Collectorate, Rajkot CDP 2005-2012 4 4 Fact File 70.20ºto 71.40ºEast (Longitude) Geographical Location 20.58ºto 23.08ºNorth (Latitude) 41ºCentigrade (Maximum) Temperature 9ºCentigrade (Minimum) Average Rainfall 540 to 600 mm Rivers Bhadar, Machhand Aji Area 11203 sq. km District Headquarter Rajkot Talukas 14 Population 31,68,392 (As per Census 2001) Population Density 283 Persons per sq. km Sex Ratio 930 Females per 1000 Males Literacy Rate 74.85% Language Gujarati, Hindi and English Seismic Zone Zone III Source : Rajkot District Collectorate, Socio Economic Profile 2006-07, Gujarat Seismic Zone Map 5 5 2 Economy and Industry Profile 6 Economy and Industry Profile § The occupational pattern in Rajkot is primarily based on manufacturing and service sector. -

Post MBBS Certificate Exam May 2017 Sr

Post MBBS Certificate Exam May 2017 Sr. No. Candidate Name Institute Teachers 1 Dr. Raj Kumar Dutta Dispur Hospital Pvt. Ltd., Guwahati Dr. Brajendra Lahkar 2 Dr. Abhishek Kumarawat Medanta the Medicity, Gurgaon Dr. Yatin Mehta 3 Dr. Gagandeep Singh Medanta the Medicity, Gurgaon Dr. Yatin Mehta 4 Dr. Sunil Kumar Karhana Fortis Memorial Research Institute,Gurgaon Dr. Sandeep Dewan 5 Dr. Neha Jain Artemis Hsopital, Gurgaon Dr. Reshma Basu 6 Dr. Shashank Shekhar Shri Action Balaji Medical Institute,New Delhi Dr. Deven Juneja 7 Dr. Quadri Sayed Mustafa Max Superspeciality Hospital, Patparganj, New Delhi Dr. Y.P. Singh 8 Dr. Smarica Artemis Hsopital, Gurgaon Dr. Jeetendra Sharma 9 Dr. Ipe K Jacob Columbia Asia Referral Hospital,Bangalore Dr. Pradeep Rangappa 10 Dr. Sameer Ali Fortis Hospital Limited, Bangalore Dr. Padmakumar A.V. 11 Dr. Vasim Raja Santokba Durlabhji Memorial Hospital, Jaipur G.R. Singhvi 12 Dr. Nirmala Nalla Gopal Gowda Shanthaveri Memorial Hospital,Mysore Dr. Raghunath Aladakatti 13 Dr. Bijal Pravinbhai Oza Santokba Durlabhji Hospital,Jaipur Dr. V.K. Parasar 14 Dr. Deboraj Dey Purkayastha Fortis Healthcare Limited, Kolkata Dr. Yashesh Paliwal 15 Dr. Swarnapali Maity Rabindranth Tagore Internationl Institute,Kolkata Dr.Animesh Gupta 16 Dr. Samrat Roy Apollo Gleneagles Hospital,Kolkata Dr.Suresh Ramasubban 17 Dr. Rathi Digant Shankarlal Dr. Jivraj Mehta Smarak Health Foundation, Ahmedabad Dr. Kalpesh K. Shah 18 Dr. Maunil Jatinkumar Shah Apollo Hospital,Ahmedabad Dr. Manoj K. Singh 19 Dr. Mohammed Aasif Shahid Ali Ansari Gujarat Research & Medical Institute, Ahmedabd Dr. M. Faruk H. Memon 20 Dr. Divyesh Gordhanbhai Sanghani Dr Jivraj Mehta Smarak Health Foundation, Ahemdabad Dr Kalpesh K Shah 21 Dr.