Cooperation Between the European Union and European Mini-States – Possible Scenarios for Future Closer and Enhanced Integration with the European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of the European Tax Havens

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Maftei, Loredana Article An Overview of the European Tax Havens CES Working Papers Provided in Cooperation with: Centre for European Studies, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University Suggested Citation: Maftei, Loredana (2013) : An Overview of the European Tax Havens, CES Working Papers, ISSN 2067-7693, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iasi, Centre for European Studies, Iasi, Vol. 5, Iss. 1, pp. 41-50 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/198228 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu AN OVERVIEW OF THE EUROPEAN TAX HAVENS Loredana Maftei* Abstract: In the actual context of economic globalization, tax havens represent a significant obstacle for global governments seeking to increase their fiscal incomes and a source of polarization of income and wealth. -

MR BONAVENTURA MONACO VIENNA MAY 14Th

MONACO ECONOMIC OUTLINE A Unique Economic Model > Tuesday, May 14th 2019 MONEGASQUES’ SINGULARITIES 2 KM2 > 37 308 Second smallest INHABITANTS country +5% 1297 POLITICAL STABILITY 139 > 8 378 NATIONALITIES CITIZENSHIPS 22% MONEGASQUES’ SINGULARITIES MONACO ECONOMIC MODEL ENGAGEMENT 1 International strategic partnerships 2 Develop expertise / Maintain Diversity / Liberal Approach to Business 3 Sustainable development the economy’s core ENVIRONNEMENT ECONOMIC GOWTHMODELECONOMIC Carbon Neutrality 0% by 2050 PILAR # 1: INTERNATIONAL STRATEGIG PARTNERSHIPS INTERNATIONAL TRADE 2 988 M € 52% GDP INT. REPRESENTATION GLOBAL PRESENCE ONU / € / OECD > 130 Intergovernmental agreements > 120 diplomatic relations A sovereignty linked to the world A strategic location with great commercial potential European Union 510 million consumers Mediterranean Basin 272 million consumers Africa Monaco st 1 commercial partner apart from Europe FOREIGN TRADE: 2000 EXPORTS 1500 1436,3 EXPORTATIONS 1355,5 • 73,7% Europe 1208,2 • 13,5% Africa 921,5 • 7,3% Asia 1000 872,2 842,2 866,2 753,2 • 4% America IMPORTATIONS • 1,6% Near & Far 500 East 119 IMPORTS 0 TRADE BALANCE 2014 2015 2016 2017 • 80% Europe • 9,4% Asia -366 • -500 -434 6,6% America -570,1 • 3,4% Africa • 0.5% Near &Far East -1000 Foreign trade- balance of trade in M € - Period 2014-2017 Sources: IMSEE – edition 2018 / Directorate-General of Customs and Indirect Taxes (France) PILAR # 2: COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE • Rising knowhow in niche markets • Fostering diversification • Maintaining Balance INNOVATION Sectors of the Monegasque economy (as % of GDP) A diversified and balanced model within a liberal environment ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT TOWARD INNOVATION IT +12% and still the best to come… STARTUP PROGRAM SMART PRINICPALITY INNOVATION AND DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION • Promote innovation, • Promote quality of life, • Create jobs and catalyze economic growth, • Deliver a new cycle of economic prosperity, • Strengthen local competitiveness. -

The United Nations' Political Aversion to the European Microstates

UN-WELCOME: The United Nations’ Political Aversion to the European Microstates -- A Thesis -- Submitted to the University of Michigan, in partial fulfillment for the degree of HONORS BACHELOR OF ARTS Department Of Political Science Stephen R. Snyder MARCH 2010 “Elephants… hate the mouse worst of living creatures, and if they see one merely touch the fodder placed in their stall they refuse it with disgust.” -Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 77 AD Acknowledgments Though only one name can appear on the author’s line, there are many people whose support and help made this thesis possible and without whom, I would be nowhere. First, I must thank my family. As a child, my mother and father would try to stump me with a difficult math and geography question before tucking me into bed each night (and a few times they succeeded!). Thank you for giving birth to my fascination in all things international. Without you, none of this would have been possible. Second, I must thank a set of distinguished professors. Professor Mika LaVaque-Manty, thank you for giving me a chance to prove myself, even though I was a sophomore and studying abroad did not fit with the traditional path of thesis writers; thank you again for encouraging us all to think outside the box. My adviser, Professor Jenna Bednar, thank you for your enthusiastic interest in my thesis and having the vision to see what needed to be accentuated to pull a strong thesis out from the weeds. Professor Andrei Markovits, thank you for your commitment to your students’ work; I still believe in those words of the Moroccan scholar and will always appreciate your frank advice. -

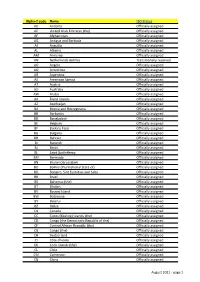

RA List of ISIN Prefixes August 2021

Alpha-2 code Name ISO Status AD Andorra Officially assigned AE United Arab Emirates (the) Officially assigned AF Afghanistan Officially assigned AG Antigua and Barbuda Officially assigned AI Anguilla Officially assigned AL Albania Officially assigned AM Armenia Officially assigned AN Netherlands Antilles Transitionally reserved AO Angola Officially assigned AQ Antarctica Officially assigned AR Argentina Officially assigned AS American Samoa Officially assigned AT Austria Officially assigned AU Australia Officially assigned AW Aruba Officially assigned AX Åland Islands Officially assigned AZ Azerbaijan Officially assigned BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Officially assigned BB Barbados Officially assigned BD Bangladesh Officially assigned BE Belgium Officially assigned BF Burkina Faso Officially assigned BG Bulgaria Officially assigned BH Bahrain Officially assigned BI Burundi Officially assigned BJ Benin Officially assigned BL Saint Barthélemy Officially assigned BM Bermuda Officially assigned BN Brunei Darussalam Officially assigned BO Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Officially assigned BQ Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba Officially assigned BR Brazil Officially assigned BS Bahamas (the) Officially assigned BT Bhutan Officially assigned BV Bouvet Island Officially assigned BW Botswana Officially assigned BY Belarus Officially assigned BZ Belize Officially assigned CA Canada Officially assigned CC Cocos (Keeling) Islands (the) Officially assigned CD Congo (the Democratic Republic of the) Officially assigned CF Central African Republic (the) -

San Marino Legal E

Study on Homophobia, Transphobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Legal Report: San Marino 1 Disclaimer: This report was drafted by independent experts and is published for information purposes only. Any views or opinions expressed in the report are those of the author and do not represent or engage the Council of Europe or the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. 1 This report is based on Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino , University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010. The latter report is attached to this report. Table of Contents A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 B. FINDINGS 3 B.1. Overall legal framework 3 B.2. Freedom of Assembly, Association and Expression 10 B.3. Hate crime - hate speech 10 B.4. Family issues 13 B.5. Asylum and subsidiary protection 16 B.6. Education 17 B.7. Employment 18 B.8. Health 20 B.9. Housing and Access to goods and services 21 B.10. Media 22 B.11. Transgender issues 23 Annex 1: List of relevant national laws 27 Annex 2: Report of Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino, University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010 31 A. Executive Summary 1. The Statutes "Leges Statuae Reipublicae Sancti Marini" that came into force in 1600 and the Laws that reform such Statutes represented the written source for excellence of the Sammarinese legal system. -

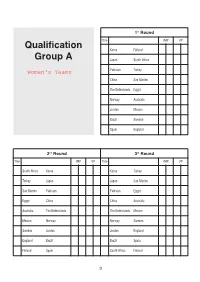

WBF Wroclaw 2016 Schedule Open

1st Round TbleIMP VP Qualification Korea Finland Group A Japan South Africa Pakistan Turkey China San Marino The Netherlands Egypt Norway Australia Jordan Mexico Brazil Sweden Spain England 2nd Round 3rd Round TbleIMP VP TbleIMP VP South Africa Korea Korea Turkey Turkey Japan Japan San Marino San Marino Pakistan Pakistan Egypt Egypt China China Australia Australia The Netherlands The Netherlands Mexico Mexico Norway Norway Sweden Sweden Jordan Jordan England England Brazil Brazil Spain Finland Spain South Africa Finland 3 4th Round 5th Round TbleIMP VP TbleIMP VP San Marino Korea Korea Egypt Egypt Japan Japan Australia Australia Pakistan Pakistan Mexico Mexico China China Sweden Sweden The Netherlands The Netherlands England England Norway Norway Spain Spain Jordan Jordan Brazil Finland Brazil San Marino South Africa South Africa Turkey Turkey Finland 6th Round 7th Round TbleIMP VP TbleIMP VP Australia Korea Korea Mexico Mexico Japan Japan Sweden Sweden Pakistan Pakistan England England China China Spain Spain The Netherlands The Netherlands Brazil Brazil Norway Norway Jordan Finland Jordan Australia South Africa South Africa Egypt Egypt Turkey Turkey San Marino San Marino Finland 4 8th Round 9th Round TbleIMP VP TbleIMP VP Sweden Korea Korea England England Japan Japan Spain Spain Pakistan Pakistan Brazil Brazil China China Jordan Jordan The Netherlands The Netherlands Norway Finland Norway Sweden South Africa South Africa Mexico Mexico Turkey Turkey Australia Australia San Marino San Marino Egypt Egypt Finland 10th Round 11th Round -

No. 1 Demography and Health in Eastern Europe and Eurasia

Working Paper Series on the Transition Countries No. 1 DEMOGRAPHY AND HEALTH IN EASTERN EUROPE AND EURASIA Ayo Heinegg Robyn Melzig James Pickett and Ron Sprout June 2005 Program Office Bureau for Europe & Eurasia U.S. Agency for International Development 1 Demography and Health in Eastern Europe and Eurasia Ayo Heinegg Academy for Educational Development Email: [email protected] Robyn Melzig U.S. Agency for International Development, Washington DC Email: [email protected] James Pickett U.S. Agency for International Development, Washington DC Email: [email protected] Ron Sprout U.S. Agency for International Development, Washington DC Email: [email protected] Abstract: Eastern Europe and Eurasia is the only region worldwide experiencing a contraction in population, which stems from both a natural decrease in the population (i.e., crude death rates exceeding crude birth rates) and emigration. The highest crude death rates in the world are found among the transition countries; so too the lowest fertility rates. This study analyzes these trends and attempts to assess some of the underlying health factors behind them. The report also examines the evidence regarding migration patterns, both political aspects (including trends in refugees and internally displaced persons) and economic aspects (including remittances, urbanization, and brain drain). 2 USAID/E&E/PO Working Paper Series on the Transition Countries September 2006 No.1 Demography and Health (June 2005) No.2 Education (October 2005) No.3 Economic Reforms, Democracy, and Growth (November 2005) No.4 Monitoring Country Progress in 2006 (September 2006) No.5 Domestic Disparities (forthcoming) No.6 Labor Markets (forthcoming) No.7 Global Economic Integration (forthcoming) The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in these working papers are entirely those of the authors. -

Andorra's Constitution of 1993

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:54 constituteproject.org Andorra's Constitution of 1993 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:54 Table of contents Preamble . 5 TITLE I: SOVEREIGNTY OF ANDORRA . 5 Article 1 . 5 Article 2 . 5 Article 3 . 5 TITLE II: RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS . 6 Chapter I: General principles . 6 Chapter II: Andorran nationality . 6 Chapter III: The fundamental rights of the person and public freedoms . 6 Chapter IV: Political rights of Andorran nationals . 9 Chapter V: Rights, and economic, social and cultural principles. 9 Chapter VI: Duties of Andorran nationals and of aliens . 11 Chapter VII: Guarantees of rights and freedoms . 11 TITLE III: THE COPRINCES . 12 Article 43 . 12 Article 44 . 12 Article 45 . 12 Article 46 . 13 Article 47 . 14 Article 48 . 14 Article 49 . 14 TITLE IV: THE GENERAL COUNCIL . 14 Article 50 . 14 Chapter I: Organization of the General Council . 14 Chapter II: Legislative procedure . 16 Chapter III: International treaties . 17 Chapter IV: Relations of the General Council with the Government . 18 TITLE V: THE GOVERNMENT . 19 Article 72 . 19 Article 73 . 19 Article 74 . 20 Article 75 . 20 Article 76 . 20 Article 77 . 20 Article 78 . 20 TITLE VI: TERRITORIAL STRUCTURE . 20 Andorra 1993 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:54 Article 79 . 20 Article 80 . 20 Article 81 . 21 Article 82 . 21 Article 83 . 22 Article 84 . 22 TITLE VII: JUSTICE . 22 Article 85 . -

Automatic Exchange of Information: Status of Commitments

As of 27 September 2021 AUTOMATIC EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION (AEOI): STATUS OF COMMITMENTS1 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES IN 2017 (49) Anguilla, Argentina, Belgium, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Bulgaria, Cayman Islands, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus2, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Finland, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Guernsey, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Isle of Man, Italy, Jersey, Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Montserrat, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Seychelles, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Turks and Caicos Islands, United Kingdom JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2018 (51) Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan3, The Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, China, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Curacao, Dominica4, Greenland, Grenada, Hong Kong (China), Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Lebanon, Macau (China), Malaysia, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Monaco, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue4, Pakistan3, Panama, Qatar, Russia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Sint Maarten4, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago4, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Vanuatu JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2019 (2) Ghana3, Kuwait5 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2020 (3) Nigeria3, Oman5, Peru3 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2021 (3) Albania3, 7, Ecuador3, Kazakhstan6 -

Report Card: Andorra

Report card Andorra Contents Page Obesity prevalence 2 Overweight/obesity by age 3 Insufficient physical activity 4 Estimated per capita fruit intake 7 Estimated per-capita processed meat intake 8 Estimated per capita whole grains intake 9 Raised blood pressure 10 Raised cholesterol 13 Raised fasting blood glucose 16 Diabetes prevalence 18 1 Obesity prevalence Adults, 2017-2018 Obesity Overweight 50 40 30 % 20 10 0 Adults Men Women Survey type: Measured Age: 18-75 Sample size: 850 Area covered: National References: 2a ENQUESTA NUTRICIONAL D’ANDORRA (ENA 2017-2018). Government of Andorra. Available at https://www.govern.ad/salut/item/download/856_fffdd95ca999812abc80e030626d6f7d (last accessed 09.09.20) Unless otherwise noted, overweight refers to a BMI between 25kg and 29.9kg/m², obesity refers to a BMI greater than 30kg/m². 2 Overweight/obesity by age Adults, 2017-2018 Obesity Overweight 70 60 50 40 % 30 20 10 0 Men Women Men Women Men Women Men Women Age 18-24 Age 25-44 Age 45-64 Age 65-74 Age 65-75 Survey type: Measured Sample size: 850 Area covered: National References: 2a ENQUESTA NUTRICIONAL D’ANDORRA (ENA 2017-2018). Government of Andorra. Available at https://www.govern.ad/salut/item/download/856_fffdd95ca999812abc80e030626d6f7d (last accessed 09.09.20) Unless otherwise noted, overweight refers to a BMI between 25kg and 29.9kg/m², obesity refers to a BMI greater than 30kg/m². 3 Cyprus Portugal Germany Malta Italy (18)30357-7 Serbia 109X Bulgaria Hungary Andorra Greece United Kingdom http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2214- Belgium Romania Slovakia Ireland Poland Slovenia Estonia Norway Czech Republic Croatia Turkey Austria 4 Latvia France Denmark Luxembourg Kazakhstan Netherlands Spain Lithuania Bosnia & Herzegovina Switzerland Sweden Armenia Ukraine Uzbekistan analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. -

An Analysis of Five European Microstates

Geoforum, Vol. 6, pp. 187-204, 1975. Pergamon Press Ltd. Printed in Great Britain The Plight of the Lilliputians: an Analysis of Five European Microstates Honor6 M. CATUDAL, Jr., Collegeville, Minn.” Summary: The mini- or microstate is an important but little studied phenomenon in political geography. This article seeks to redress the balance and give these entities some of the attention they deserve. In general, five microstates are examined; all are located in Western Europe-Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican. The degree to which each is autonomous in its internal affairs is thoroughly explored. And the extent to which each has control over its external relations is investigated. Disadvantages stemming from its small size strike at the heart of the ministate problem. And they have forced these nations to adopt practices which should be of use to large states. Zusammenfassung: Dem Zwergstaat hat die politische Geographie wenig Beachtung geschenkt. Urn diese Liicke zu verengen, werden hier fiinf Zwergstaaten im westlichen Europa untersucht: Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, San Marino und der Vatikan. Das Ma13der inneren und lul3eren Autonomie wird griindlich untersucht. Die Kleinheit hat die Zwargstaaten zu Anpassungsformen gezwungen, die such fiir groRe Staaten van Bedeutung sein k8nnten. R&sum& Les Etats nains n’ont g&e fait I’objet d’Btudes de geographic politique. Afin de combler cette lacune, cinq mini-Etats sent examines ici; il s’agit de I’Andorre, du Liechtenstein, de Monaco, de Saint-Marin et du Vatican. Dans quelle mesure ces Etats disposent-ils de l’autonomie interne at ont-ils le contrble de leurs relations extirieures. -

Flash Reports on Labour Law November 2019 Summary and Country Reports

Flash Reports on Labour Law November 2019 Summary and country reports Written by The European Centre of Expertise (ECE), based on reports submitted by the Network of Labour Law Experts November 2019 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Unit B.2 – Working Conditions Contact: Marie LAGUARRIGUE E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels Flash Report 11/2019 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s). The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person/organisation acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of any information contained in this publication. This publication has received financial support from the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation "EaSI" (2014-2020). For further information please consult: http://ec.europa.eu/social/easi. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019 ISBN ABC 12345678 DOI 987654321 © European Union, 2019 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.