Barbie and Exceptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

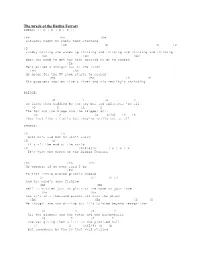

The Wreck of the Barbie Ferrari INTRO: |: D | D | D | D :|

The wreck of the Barbie Ferrari INTRO: |: D | D | D | D :| |Em |Em |Em Saturday night he comes home stinking |Em |D |D |D |D sunday morning she wakes up thinking and thinking and thinking and thinking |Em |Em |Em does she need to get the kids dressed to go to church |Em He's pulled a shotgun out of the lurch |Em |Em He heads for the TV room starts to search |Em |Em |D |D His problems swollen like a river and his reality's shrinking BRIDGE: |G D |A D He finds them huddled by the toy box and splatters 'em all |G D |A D The Ken and the midge and the skipper doll |G D |A (2/4) |B |B They look like a family but they're really not at all CHORUS: |A |A Well he's sad but he ain't sorry |A |G It ain't the end of the world |G |G(2/4)|D | D | D | D It's just the wreck of the Barbie Ferrari |Em |Em |Em He wonders if he ever said I do |Em To that little blonde plastic voodoo |D |D |D |D And his mind's gone fishing |Em |Em Well it started just as plain as the nose on your face |Em |Em now it's in a thousand pieces all over the place |Em |Em |D |D He thought she was driving but it's twisted beyond recognition |G D |A D All the diapers and the tutus and the basketballs |G D |A D she was giving them a lift to the promised mall |G D |A(2/4) |B |B But somewhere by the TV that V-12 stalled |A |A As he loaded the chamber her eyes got starry |A |G It ain't the end of the world |G |G /2/4) |D It's just wreck of the Barbie Ferrari |G D |A D It's just wreck of the Barbie Ferrari |G D |A D It's just wreck of the Barbie Ferrari |G D |A(2/4) |B |B When they get home from church won't they be sorry |A |A He's cornered 'em all on his urban safari |A |G It ain't the end of the world.. -

Mattel V Walking Mountain Productions.Malted Barbie

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT MATTEL INC., a Delaware Corporation, No. 01-56695 Plaintiff-Appellant, C.D. Cal. No. v. CV-99-08543- RSWL WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS, a California Business Entity; TOM N.D. Cal. No. FORSYTHE, an individual d/b/a CV-01-0091 Walking Mountain Productions, Misc. WHA Defendants-Appellees. MATTEL INC., a Delaware No. 01-57193 Corporation, Plaintiff-Appellee, C.D. Cal. No. CV-99-08543- v. RSWL WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS, N.D. Cal. No. a California Business Entity; TOM CV-01-0091 FORSYTHE, an individual d/b/a Misc. WHA Walking Mountain Productions, Defendants-Appellants. OPINION Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Ronald S.W. Lew, District Judge, Presiding and United States District Court for the Northern District of California William H. Alsup, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted March 6, 2003—Pasadena, California 18165 18166 MATTEL INC. v. WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS Filed December 29, 2003 Before: Harry Pregerson and Sidney R. Thomas, Circuit Judges, and Louis F. Oberdorfer, Senior District Judge.* Opinion by Judge Pregerson *The Honorable Louis F. Oberdorfer, Senior Judge, United States Dis- trict Court for the District of Columbia, sitting by designation. 18170 MATTEL INC. v. WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS COUNSEL Adrian M. Pruetz (argued), Michael T. Zeller, Edith Ramirez and Enoch Liang, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart Oliver & Hedges, LLP, Los Angeles, California, for the plaintiff-appellant- cross-appellee. Annette L. Hurst (argued), Douglas A. Winthrop and Simon J. Frankel, Howard, Rice, Nemerovski, Canady, Falk & Rab- kin, APC, San Francisco, California, and Peter J. -

Masters of the Universe: Action Figures, Customization and Masculinity

MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE: ACTION FIGURES, CUSTOMIZATION AND MASCULINITY Eric Sobel A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2018 Committee: Montana Miller, Advisor Esther Clinton Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Montana Miller, Advisor This thesis places action figures, as masculinely gendered playthings and rich intertexts, into a larger context that accounts for increased nostalgia and hyperacceleration. Employing an ethnographic approach, I turn my attention to the under-discussed adults who comprise the fandom. I examine ways that individuals interact with action figures creatively, divorced from children’s play, to produce subjective experiences, negotiate the inherently consumeristic nature of their fandom, and process the gender codes and social stigma associated with classic toylines. Toy customizers, for example, act as folk artists who value authenticity, but for many, mimicking mass-produced objects is a sign of one’s skill, as seen by those working in a style inspired by Masters of the Universe figures. However, while creativity is found in delicately manipulating familiar forms, the inherent toxic masculinity of the original action figures is explored to a degree that far exceeds that of the mass-produced toys of the 1980s. Collectors similarly complicate the use of action figures, as playfully created displays act as frames where fetishization is permissible. I argue that the fetishization of action figures is a stabilizing response to ever-changing trends, yet simultaneously operates within the complex web of intertexts of which action figures are invariably tied. To highlight the action figure’s evolving role in corporate hands, I examine retro-style Reaction figures as metacultural objects that evoke Star Wars figures of the late 1970s but, unlike Star Wars toys, discourage creativity, communicating through the familiar signs of pop culture to push the figure into a mental realm where official stories are narrowly interpreted. -

Who Is Really Protecting Barbie

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 7-1-2008 Who is really protecting Barbie: Goliath or the Silver Knight? A defense of Mattel's aggressive international attemps to protect its Barbie copyright and trademark Liz Somerstein Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Liz Somerstein, Who is really protecting Barbie: Goliath or the Silver Knight? A defense of Mattel's aggressive international attemps to protect its Barbie copyright and trademark, 39 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 559 (2008) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol39/iss3/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Who is really protecting Barbie: Goliath or the Silver Knight? A defense of Mattel's aggressive international attempts to protect its Barbie copyright and trademark Liz Somerstein* INTRODUCTION .............................................. 559 I. LEGAL REALISM: AN OVERVIEW ....................... 562 II. MATTEL'S AMERICAN BATTLE: MATTEL, INC. V. WALKING MOUNTAIN PRODUCTIONS ................... 563 A. The Walking Mountain case: Background ........ 565 B. The Walking Mountain Court's Analysis ......... 567 i. Purpose and character of use ................ 568 ii. Nature of the copyrighted work .............. 570 iii. Amount and substantiality of the portion u sed ......................................... 570 iv. Effect upon the potential market ............ 571 III. AT LOOK AT WALKING MOUNTAIN UNDER THE LEGAL REALIST LENS ....................................... -

List of Intellivision Games

List of Intellivision Games 1) 4-Tris 25) Checkers 2) ABPA Backgammon 26) Chip Shot: Super Pro Golf 3) ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS 27) Commando Cartridge 28) Congo Bongo 4) ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS 29) Crazy Clones Treasure of Tarmin Cartridge 30) Deep Pockets: Super Pro Pool and Billiards 5) Adventure (AD&D - Cloudy Mountain) (1982) (Mattel) 31) Defender 6) Air Strike 32) Demon Attack 7) Armor Battle 33) Diner 8) Astrosmash 34) Donkey Kong 9) Atlantis 35) Donkey Kong Junior 10) Auto Racing 36) Dracula 11) B-17 Bomber 37) Dragonfire 12) Beamrider 38) Eggs 'n' Eyes 13) Beauty & the Beast 39) Fathom 14) Blockade Runner 40) Frog Bog 15) Body Slam! Super Pro Wrestling 41) Frogger 16) Bomb Squad 42) Game Factory 17) Boxing 43) Go for the Gold 18) Brickout! 44) Grid Shock 19) Bump 'n' Jump 45) Happy Trails 20) BurgerTime 46) Hard Hat 21) Buzz Bombers 47) Horse Racing 22) Carnival 48) Hover Force 23) Centipede 49) Hypnotic Lights 24) Championship Tennis 50) Ice Trek 51) King of the Mountain 52) Kool-Aid Man 80) Number Jumble 53) Lady Bug 81) PBA Bowling 54) Land Battle 82) PGA Golf 55) Las Vegas Poker & Blackjack 83) Pinball 56) Las Vegas Roulette 84) Pitfall! 57) League of Light 85) Pole Position 58) Learning Fun I 86) Pong 59) Learning Fun II 87) Popeye 60) Lock 'N' Chase 88) Q*bert 61) Loco-Motion 89) Reversi 62) Magic Carousel 90) River Raid 63) Major League Baseball 91) Royal Dealer 64) Masters of the Universe: The Power of He- 92) Safecracker Man 93) Scooby Doo's Maze Chase 65) Melody Blaster 94) Sea Battle 66) Microsurgeon 95) Sewer Sam 67) Mind Strike 96) Shark! Shark! 68) Minotaur (1981) (Mattel) 97) Sharp Shot 69) Mission-X 98) Slam Dunk: Super Pro Basketball 70) Motocross 99) Slap Shot: Super Pro Hockey 71) Mountain Madness: Super Pro Skiing 100) Snafu 72) Mouse Trap 101) Space Armada 73) Mr. -

An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer

Cybaris® Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 2015 An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests Amanda Schreyer Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Schreyer, Amanda (2015) "An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balancing Public and Private Interests," Cybaris®: Vol. 6: Iss. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/cybaris/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cybaris® by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Schreyer: An Overview of Legal Protection for Fictional Characters: Balanci Published by Mitchell Hamline Open Access, 2015 1 Cybaris®, Vol. 6, Iss. 1 [2015], Art. 3 AN OVERVIEW OF LEGAL PROTECTION FOR FICTIONAL CHARACTERS: BALANCING PUBLIC AND PRIVATE INTERESTS † AMANDA SCHREYER I. Fictional Characters and the Law .............................................. 52! II. Legal Basis for Protecting Characters ...................................... 53! III. Copyright Protection of Characters ........................................ 57! A. Literary Characters Versus Visual Characters ............... 60! B. Component Parts of Characters Can Be Separately Copyrightable ................................................................ -

Read Book Bananagrams! for Kids

BANANAGRAMS! FOR KIDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joe Edley,Rena Nathanson,Abe Nathanson | 160 pages | 27 Aug 2010 | Workman Publishing | 9780761158448 | English | New York, United States Bananagrams! For Kids PDF Book Leave this field empty. Hollywood Rides. Jenny says:. Perfectly Cute. Place all the tiles facedown, then flip over 21 tiles. Amy Goldstein is an expert puzzle maker. Please help us continue to provide you with our trusted how-to guides and videos for free by whitelisting wikiHow on your ad blocker. North Star Games. September 23, at pm. Simmons Drums. Cart Total:. Trisha added it Apr 19, Questions For Similar Products. The Northwest Company. Then, all players help in creating one large interlocking word grid. Disney Princess. I DIG Exploding Kittens. Answers included for all puzzles. Your Cart. Search by title, catalog stock , author, isbn, etc. Stomp Rocket. Along with Robert Leighton and Amy Goldstein, he founded the company Puzzability, which creates unique and challenging puzzles for kids and adults. July 29, at am. New York Giants. Free 2-Day Shipping. Your tiles will get mixed up, so make sure to sort them back out at the end. Bananagrams Game. Bananagrams! For Kids Writer There are over a dozen of banana-themed varieties, including Bunched Up a mini-crossword , Monkey in the Middle building a larger word out of two smaller words, with clues , Banana Pancakes a stack of anagrams using letters in common , and Going Bananas complete a sentence with two different words made from the same letters. Pittsburgh Steelers. Details if other :. My First Bananagrams is a multi-award-winning word-game for kids. -

Interns Volunteer at TMC Health Fair

Vol. 26, Issue 4 | July/August 2014 Page 4 Cleveland University quick quiz Wanna win big? inVol. 26, Issue 4 | July/August 2014touch It’s fun and easy to play. And you really A newsletter for the students, faculty & staff of Cleveland University-Kansas City don’t need a big brain to win. Just do a little research, either on the Interns volunteer at TMC health fair leveland Chiropractic College Linda Gerdes, community outreach Internet or otherwise, Pe ter Conce again answered the call manager, worked with Moore and Dr. to serve others as a large contingent Debra Robertson-Moore to prepare for and you’ll be well of Clevelanders participated in the 4th the health fair. Although the commit- on your way! Annual Touchdown Family Fest, July 19 ment of time and energy were substan- at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City. tial, the results were worth the effort. Sponsored by Truman Medical Center “There is a lot of time and work in- To enter the “Quick Quiz” (TMC), the day-long event offered free, volved in organizing such a large event,” basic health care services to those in need, Gerdes said. “But when you see all the trivia contest, submit your That’s so totally random. including dental and vision screenings for people you are helping, it makes all the answer either via email to children and adults, as well as adult phys- hard work worth it, and hopefully teaches [email protected] A little more than nine years ago, we launched the first in a series of “totally random” trivia questions icals and youth sports physicals. -

A509167 PDF Art of He Man and the Masters of the Universe Various

PDF Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Various - free pdf download Download Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe PDF, PDF Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Popular Download, Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Full Collection, I Was So Mad Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Various Ebook Download, Free Download Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Full Version Various, online free Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe, Download PDF Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe, pdf free download Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe, by Various Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe, pdf Various Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe, Various ebook Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe, Download Online Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Book, Read Online Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe E-Books, Read Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Full Collection, Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe pdf read online, Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Popular Download, Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Free PDF Online, Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Books Online, PDF Download Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Free Collection, Free Download Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Books [E-BOOK] Art Of He Man And The Masters Of The Universe Full eBook, DOWNLOAD CLICK HERE There 's no development in each story to highlight the events. -

{PDF} He Man the Eternity War: Volume 1

HE MAN THE ETERNITY WAR: VOLUME 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Pop Mahn,Dan Abnett | 144 pages | 20 Oct 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401258481 | English | United States He Man the Eternity War: Volume 1 PDF Book The book falls apart fast for me after that. Bradley rated it really liked it Aug 06, Masters of the Universe. This will likely increase the time it takes for your changes to go live. What sacrifices must He-Man make to salvage his family legacy? Vladimir rated it liked it Feb 01, Lists with This Book. I am bias to He-Man and his friends due to a childhood of adventures, but this seems to enhance the adventures instead of hurting them. It was the only issue since this DC relaunch in where it actually felt like the author or artist remembered what it was like to actually play with these characters back in the day. To what lengths will the Masters of the Universe go to reclaim their kingdom? Characters are hacked to pieces and slashed apart in some shocking moments, but they are smart enough not to just eliminate the main characters that people love. Welcome back. He Man and the Masters of the Multiverse [18]. Almost every child my generation knows about He-Man, given the lack of choices we have in choosing which cartoons we had to watch. Born to both the surface and the sea, Arthur Curry walks in two worlds but can find a home in neither. Now, Atlantis has been cut off from the rest of the world, trapped by powerful ancient magic called the Crown of Thorns. -

Animoca Brands Launches He-Man™ Tappers of Grayskull™

Animoca Brands launches He-Man™ Tappers of Grayskull™ ● Animoca Brands launches He-ManTM Tappers of GrayskullTM based on the Masters of the Universe® franchise ● The new game features voice-over acting by the legendary Alan Oppenheimer and Cam Clarke, the official voices of Skeletor® and He-Man/Prince Adam, respectively ● The Masters of the Universe brand is estimated to have over 30 million fans worldwide ● Further games based on Mattel properties arriving in 2016; Animoca Brands will launch its first e-book based on Thomas & Friends™ in the September quarter Hong Kong, 31 August 2016 - Animoca Brands (ASX: AB1, ‘the Company’) today announced the launch of its latest mobile game, He-ManTM Tappers of GrayskullTM. The game is based on the iconic Masters of the Universe® franchise, launched in 1982. He-Man Tappers of Grayskull is available globally on iPhone®, iPad® and iPod touch® on the App Store℠, and for Android™ devices on Google Play™. In He-Man Tappers of Grayskull, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe battle Skeletor and his magically enlarged minions across multiple locations on the planet Eternia®. He-Man and his allies must secure powerful ancient artifacts and defeat wave after wave of gigantic foes to stop Skeletor’s evil plans, thus ensuring safety for Castle Grayskull® and all Eternia. The app utilises clicker gameplay and features dozens of Masters of the Universe characters including He-Man®, Skeletor®, Teela®, Man-At-Arms®, Battle Cat®, She-Ra®, Orko®, Evil-Lyn®, Beast Man®, Mer-Man®, Sorceress®, Stratos®, Mekaneck®, Scareglow™, Hordak® and others. He-Man Tappers of Grayskull boasts voice acting by the Emmy Award-nominated Alan Oppenheimer (Skeletor) and Cam Clarke (He-Man, Prince Adam). -

Barbie® Doll's Friends and Relatives Since 1980

BARBIE® DOLL’S FRIENDS AND RELATIVES SINCE 1980 1980 1987 Beauty Secrets Christie #1295 Jewel Secrets Ken #1719 Kissing Christie #2955 Jewel Secrets Ken (African American) #3232 Scott (Skippers Boyfriend) #1019 Jewel Secrets Whitney #3179 Sport and Shave Ken #1294 Jewel Secrets Skipper #3133 Sun Lovin’ Malibu Christie #7745 Revised Rocker Dana #3158 Sun Lovin’ Malibu P.J. #1187 Revised Rocker Dee Dee #3160 Sun Lovin’ Malibu Skipper #1019 Revised Rocker Derek #3137 Super Teen Skipper #2756 Revised Rocker Diva #3159 Revised Rocker Ken #3131 1981 Golden Dream Christie #3249 1988 Roller Skating Ken #1881 California Dream Christie #4443 California Dream Ken #4441 1982 California Dream Midge #4442 Star Ken #3553 California Dream Teresa #5503 Fashions Jeans Ken #5316 Cheerleader Teen Skipper #5893 Pink and Pretty Christie #3555 Island Fun Christie #4092 Sunsational Malibu Christie #7745 Island Fun Miko #4065 Sunsational Malibu P.J. #1187 Island Fun Skipper #4064 Sunsational Malibu Ken #1088 Island Fun Steven #4093 Sunsational Malibu Ken (African American) #3849 Island Fun Teresa #4117 Sunsational Malibu Skipper #1069 Party Teen Skipper #5899 Western Ken #3600 Perfume Giving Ken #4554 Perfume Giving Ken (African American) #4555 1983 Perfume Giving Whitney #4557 Barbie & Friends Pack #4431 Sensation Becky #4977 Dream Date Ken #4077 Sensation Belinda #4976 Dream Date P.J. #5869 Sensation Bobsy #4967 Horse Lovin’ Ken #3600 Teen Sweetheart Skipper #4855 Horse Lovin’ Skipper #5029 Workout Teen Skipper #3899 Todd (Ken’s Handsome Friend) #4253 Tracy (Barbie’s Beautiful Friend) #4103 1989 Animal Lovin’ Ken #1351 1984 Animal Lovin’ Nikki #1352 Crystal Ken #4898 Beach Blast Christie #3253 Great Shape Ken #7318 Beach Blast Ken #3238 Great Shape Skipper #7414 Beach Blast Miko #3244 Sun Gold Malibu Ken #1088 Beach Blast Skipper #3242 Sun Gold Malibu P.J.