Case 4:16-Cv-02041-HSG Document 68 Filed 08/23/18 Page 1 of 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Membership Lists, Metadata, and Freedom of Association's Specificity Requirement

Membership Lists, Metadata, and Freedom of Association's Specificity Requirement KATHERINE J. STRANDBURG* Over the past year, documents revealed by leaker Edward Snowden and declassified by the government have provided a detailed look at some aspects of the National Security Agency's (NSA's) surveillance of electronic communications and transactions. Attention has focused on the NSA's mass collection from major telecommunications carriers of so-called "telephony metadata," which includes dialing and dialed numbers, call time, duration, and the like.' The goal of comprehensive metadata collection is what I have elsewhere called "relational surveillance"2-to follow "chains of communications" between "telephone numbers associated with known or suspected terrorists and other telephone numbers" and then to "analyze those connections in a way that can help identify terrorist * Alfred B. Engelberg Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. Professor Strandburg acknowledges the generous support of the Filomen D'Agostino and Max E. Greenberg Research Fund. 1 The term "metadata" has been widely adopted in discussing the NSA's data collection activities and so I will use it here. When one moves beyond call traffic data, however, the term's meaning in the data surveillance context is problematic, ill-defined and may obscure the need for careful analysis. As one illustration of these issues, consider NSA documents recently made public in connection with news reports of NSA monitoring of text messages, which refer, in language that would have made the Red Queen proud, to "content derived metadata." See James Ball, NSA DishfirePresentation on Text Message Collection-Key Extracts, THE GUARDIAN, Jan. -

Summary of U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Law, Practice, Remedies, and Oversight

___________________________ SUMMARY OF U.S. FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE LAW, PRACTICE, REMEDIES, AND OVERSIGHT ASHLEY GORSKI AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION AUGUST 30, 2018 _________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS QUALIFICATIONS AS AN EXPERT ............................................................................................. iii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 I. U.S. Surveillance Law and Practice ................................................................................... 2 A. Legal Framework ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Presidential Power to Conduct Foreign Intelligence Surveillance ....................... 3 2. The Expansion of U.S. Government Surveillance .................................................. 4 B. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 ..................................................... 5 1. Traditional FISA: Individual Orders ..................................................................... 6 2. Bulk Searches Under Traditional FISA ................................................................. 7 C. Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act ........................................... 8 D. How The U.S. Government Uses Section 702 in Practice ......................................... 12 1. Data Collection: PRISM and Upstream Surveillance ........................................ -

S. 1123, the USA Freedom Act of 2015 Dear Members of the Senate

WASHINGTON LEGISLATIVE OFFICE May 23, 2015 RE: S. 1123, the USA Freedom Act of 2015 Dear Members of the Senate: Section 215 of the Patriot Act expanded the reach of the intelligence agencies in unprecedented ways and is the basis for collecting and retaining records on AMERICAN CIVIL millions of innocent Americans. The ACLU opposed Section 215 when it LIBERTIES UNION WASHINGTON was introduced, has fought it at each successive reauthorization, and urges LEGISLATIVE OFFICE Congress to let it sunset on June 1st. 915 15th STREET, NW, 6 TH FL WASHINGTON, DC 20005 T/202.544.1681 F/202.546.0738 This week, the Senate is scheduled to vote on S. 1123, the USA Freedom Act WWW.ACLU.ORG of 2015, which proposes modest reforms to Section 215, Section 214 (the pen MICHAEL W. MACLEOD-BALL register and trap and trace device provision, “PR/TT”), and national security ACTING DIRECTOR letter authorities. The bill also seeks to increase transparency over government NATIONAL OFFICE surveillance activities but could be construed to codify a new surveillance 125 BROAD STREET, 18 TH FL. regime of more limited, yet still massive scope. NEW YORK, NY 10004-2400 T/212.549.2500 Earlier this month, the Second Circuit unequivocally ruled that the OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS 1 SUSAN N. HERMAN government’s bulk metadata program violated the law. In light of this PRESIDENT decision, it is clear that more robust surveillance reform is needed. Though an ANTHONY D. ROMERO improvement over the status quo in some respects, the USA Freedom Act EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR does not go far enough to rein in NSA abuses and contains several concerning ROBERT REMAR provisions. -

Introduction the Intelligence Community (IC) – General Information

Guide to Posted Documents Regarding Use of National Security Authorities – Updated as of January, 2020 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 The Intelligence Community (IC) – General Information .............................................................................. 1 IC Framework for Protecting Civil Liberties and Privacy and Enhancing Transparency ................................ 3 Reports on Use of National Security Authorities. ......................................................................................... 5 Section 702: - Overviews............................................................................................................................... 6 Section 702: Targeting and Minimization ..................................................................................................... 7 Section 702: Compliance, Oversight, and Other Documents ....................................................................... 8 FISA: Other Provisions ................................................................................................................................... 9 FISA: FISC and FISCR Opinions..................................................................................................................... 10 Executive Order 12333 ................................................................................................................................ 11 Presidential -

IN the EUROPEAN COURT of HUMAN RIGHTS App No. 24960/15 10 HUMAN RIGHTS

IN THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS App No. 24960/15 10 HUMAN RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS AND OTHERS – v – THE UNITED KINGDOM THIRD PARTY INTERVENTION OF THE ELECTRONIC PRIVACY INFORMATION CENTER Introduction 1. The Electronic Privacy Information Center (“EPIC”) welcomes the opportunity to submit these written comments pursuant to leave granted on February 26, 2016, by the President of the First Section under Rule 44 §3 of the Rules of the Court. These submissions do not address the facts or merits of the applicants’ case. 2. EPIC is a public interest, non-profit research and educational organization based in Washington, D.C. 1 EPIC was established in 1994 to focus public attention on emerging privacy and civil liberties issues and to protect privacy, freedom of expression, and democratic values in the information age. EPIC routinely files amicus briefs in U.S. courts, pursues open government cases, defends consumer privacy, coordinates non- profit participation in international policy discussions, and advocates before legislative and judicial organizations about emerging privacy and civil liberties issues. EPIC is a leading privacy and freedom of information organization in the US with special expertise in government surveillance related legal matters. 3. The matter before the Court in 10 Human Rights Organizations and Others v. the United Kingdom impacts the human rights to privacy, data protection and freedom of expression of people around the world, which is reflected also by the variety of the applicants’ affiliations. The matter before the Court is an issue of broad international importance because it involves arrangements to transfer personal data between the United States and European countries. -

H.R. 3361, the USA FREEDOM ACT FACT SHEET

H.R. 3361, The USA FREEDOM ACT FACT SHEET The USA FREEDOM Act reforms intelligence-gathering programs to enhance civil liberty protections while preserving traditional operational capabilities to protect national security. The Act prohibits the bulk collection of records under Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act; the FISA pen register, trap and trace statute; and the national security letter statutes. This goes further than the President’s plan in that it prohibits the bulk collection of all tangible things and not just telephone records. The Act preserves traditional operational capabilities. The government may continue to collect foreign intelligence information under each of these authorities. However, the government must now base the use of these authorities on a “specific selection term” defined to preclude indiscriminate, bulk record collection. The Act creates a new, narrowly-tailored authority for the collection of call detail records. This new authority leaves the records in the hands of the providers, is limited to only international terrorism investigations, and requires the government to obtain a court order on a case-by-case basis to request the records from the providers. The Act imposes limitations on the new call detail record authority. Production of call detail records cannot exceed 180 days unless the government seeks permission of the court to renew the order. The government is limited to only two “hops”—i.e., the call detail records associated with the initial seed and the call detail records associated with the records returned in the initial “hop.” The government is also required to promptly destroy records that do not contain foreign intelligence information. -

SPECIAL REPORT ESPIONAGE November 12Th 2016 Shaken and Stirred

SPECIAL REPORT ESPIONAGE November 12th 2016 Shaken and stirred 20161012_SR_ESPIONAGE_001.indd 1 27/10/2016 13:41 SPECIAL REPORT ESPIONAGE Shaken and stirred Intelligence services on both sides of the Atlantic have struggled to come to terms with new technology and a new mission. They are not done yet, writes Edward Carr IN THE SPRING thaw of 1992 a KGB archivist called Vasili Mitrokhin CONTENTS walked into the British embassy in Riga. Stashed at the bottom ofhis bag, beneath some sausages, were copies of Soviet intelligence files that he 5 Technology had smuggled out of Russia. Before the year was out MI6, Britain’s for- Tinker, tailor, hacker, spy eign-intelligence service, had spirited away Mitrokhin, his family and six large cases packed with KGB records which he had kept hidden in a milk 7 Governance Standard operating churn and some old trunks under the floor ofhis dacha. procedure The pages of “The Mitrokhin Archive”, eventually published in 1999, are steeped in vodka and betrayal. They tell the stories of notorious 8 Edward Snowden spies like Kim Philby, a British intelligence officer who defected to Russia You’re US government in 1963. And they exposed agents like Melita Norwood, who had quietly property worked for the KGB for 40 years from her home in south-east London, then shot to fame as a great-gran- 10 China and Russia Happenstance and enemy ny. Her unrelenting Marxist refus- action al to shop at Britain’s capitalist su- permarkets earned her the 12 How to do better headline: “The Spy Who Came in The solace of the law from the Co-op”. -

Report on the Government's Use of the Call Detail Records Program

Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board Report on the Government’s Use of the Call Detail Records Program Under the USA Freedom Act Working to ensure that efforts by the Executive Branch to protect the nation from terrorism appropriately safeguard privacy and civil liberties. February 2020 Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board • PCLOB.gov • [email protected] TOP SECRET//SI//NOFORN Board Members Adam I. Klein, Chairman Jane E. Nitze Edward W. Felten Travis LeBlanc Aditya Bamzai TOP SECRET//SI//NOFORN TOP SECRET//SI//NOFORN Table of Contents (U) Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 I. (U) Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 4 II. (U) NSA’s Collection of CDRs under the USA Freedom Act ............................................ 13 III. (U) Operational Use of the USA Freedom Act CDR Program ............................................ 25 IV. (U) Legal Analysis ............................................................................................................... 33 V. (U) Analysis of Privacy Risks.............................................................................................. 53 VI. (U) Statement of Chairman Adam Klein ............................................................................. 59 VII. (U) Statement of Board Members Ed Felten and Travis LeBlanc ....................................... 68 VIII. (U) Statement -

The Structural Constitution and the Challenge of Mass Surveillance

Before Privacy, Power: The Structural Constitution and the Challenge of Mass Surveillance Deborah Pearlstein* INTRODUCTION The rich legal literature that has grown up to assess the constitutionality of bulk communications collection by the government has focused overwhelmingly—and understandably—on the challenge such programs pose to particular claims of individual right against the state. For scholars focused on the Fourth Amend- ment,1 bulk collection threatens the constitutional protection of the “privacy, dignity, and security of persons against certain arbitrary and invasive acts” by the government,2 and in particular implicates the prohibition against warrantless searches that violate an individual’s “reasonable expectation of privacy.”3 Less frequently, scholars have highlighted various First Amendment interests impli- cated by bulk data collection—the danger that government collection may chill individual associational and expressive activities,4 as well as the intellectual freedom to think and explore ideas and information without fear of state record keeping.5 While varying widely in its conclusions, this work generally begins by conceptualizing the potential constitutional harm such programs pose as arising in discrete areas of the doctrinal Bill of Rights. Yet attempting to describe what seems troubling about bulk collection in terms of individual rights alone has significant doctrinal and conceptual limits. In doctrinal terms, for instance, Fourth Amendment jurisprudence has not yet identified any constitutionally cognizable harm when the government searches information that has been shared with a third party—even in an era when vast quantities of individuals’ most intimate data is possessed in electronic form by * Professor, Cardozo Law School, Yeshiva University. The author wishes to thank William C. -

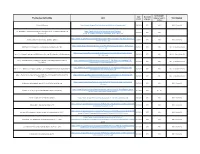

ICOTR Transparency Tracker

Subject matter Date Document category (used in Posting description/title Link posted orig. year Subcategory charts) Section 702 Overview https://www.dni.gov/files/icotr/Section702-Basics-Infographic.pdf 12/20/2017 2017 FISA FISA - Section 702 Fact Sheet: Guide to Posted Documents Regarding Use of National Security Authorities - Updated as of https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Updated- 12/12/2017 2017 FISA December 2017 Guide_to_Posted_Documents_December_2017_FINAL.pdf https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Updated-Guide-to-Section-702-Value-Examples--- Fact Sheet: Guide to Section 702 Value Examples - Updated 12/7/2017 2017 FISA FISA - Section 702 Dec-2017-FINAL.pdf https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/CLPT-USP-Dissemination-Paper---FINAL-clean- ODNI Report on Protecting U.S. Person Identities in Disseminations under FISA 11/20/2017 2017 FISA Title I, Title III, and Section 702 11.17.17.pdf https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Annex-1-NSA-CLPO-Dissemination-Report- Annex 1 - The National Security Agency’s (NSA) Report on Protecting USP Information in FISA Disseminations 11/20/2017 2017 FISA Title I, Title III, and Section 702 20171027.pdf Annex 2 - The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Report on Protecting USP Information in FISA https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Annex-2---FBI-Report-on-Protecting-USP- 11/20/2017 2017 FISA Title I, Title III, and Section 702 Disseminations Information-in-FISA-Disseminations.pdf https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/icotr/Annex-3---CIA-Report-on-Protecting-USP- Annex 3 - -

Submission to Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Standing Committee Inquiry on Comprehensive Revision of Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979

Submission to Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Standing Committee Inquiry on Comprehensive Revision of Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 This submission is based entirely upon publicly available sources. The list of appendices at the back does not appear in order of mention. Appendices are accessible via control/click from the text. Some surveillance programs are not named but shown as eg. A-redact Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................4 Programs...................................................................................................................8 Operating bases in Australia...................................................................................8 National legislation on surveillance ............................................................................8 UKUSA and people ..................................................................................................9 Monitoring agencies in Australia which have an impact on human rights and privacy.....................................................................................................................11 Queries to our watchdogs ......................................................................................11 Emanation security ................................................................................................11 Legislative protections for citizens ...........................................................................11 -

Freedom Act Limits NSA Phone Surveillance

Editor: Henry Reichman, California State University, East Bay Founding Editor: Judith F. Krug (1940–2009) Publisher: Barbara Jones Office for Intellectual Freedom, American Library Association ISSN 1945-4546 July 2015 Vol. LXIV No. 4 www.ala.org/nif In a significant scaling back of national security policy formed after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the Senate on June 2 approved legislation curtailing the federal government’s sweeping surveillance of American phone records, and President Obama signed the measure hours later. The passage of the bill—achieved over the fierce opposition of the Senate major- ity leader—will allow the government to restart surveillance operations, but with new restrictions. The legislation signaled a cultural turning point for the nation, almost 14 years after the September 11 attacks heralded the construction of a powerful national security apparatus. Freedom The shift against the security state began with the revelations by Edward J. Snowden, a former National Security Agency contractor, about the bulk collection of phone records. Act limits The backlash was aided by the growth of interconnected communication networks run by companies that have felt manhandled by government prying. The storage of those records now shifts to the phone companies, and the government must petition a special federal NSA phone court for permission to search them. Even with the congressional action, the government will continue to maintain robust surveillance surveillance power, an authority highlighted by Senator Rand Paul, Republican of Ken- tucky, whose opposition to the phone records program forced it to be shut down at 12:01 a.m. June 1.