00 Ekechi Auto1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![MBAITOLI USA NATIONAL INC. [A Non-Profit and Charitable Organization] 1057 Hyde Park Avenue Email: Mbaitoli@Gmail.Com Hyde Park, MA 02136](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3953/mbaitoli-usa-national-inc-a-non-profit-and-charitable-organization-1057-hyde-park-avenue-email-mbaitoli-gmail-com-hyde-park-ma-02136-53953.webp)

MBAITOLI USA NATIONAL INC. [A Non-Profit and Charitable Organization] 1057 Hyde Park Avenue Email: [email protected] Hyde Park, MA 02136

MBAITOLI USA NATIONAL INC. [A non-profit and charitable organization] 1057 Hyde Park Avenue Email: [email protected] Hyde Park, MA 02136 www.mbaitoli.org Mbaitoli, my Mbaitoli ... an address by Martin Dimunah, President, Mbaitoli USA Distinguished ladies and Gentlemen, Good evening and welcome to Boston, the “intellectual hub of America. I begin this address with a brief overview about Mbaitoli. As the name implies, it is made up Officers: of nine towns: Afara, Eziama-Obiato, Ogbaku, Ogwa, Orodo, Ifakala, Mbieri, Ubomiri and Umunoha. It is located in the center of Imo State and is a part of Owerri capital territory. Today, Boston is more Martin Dimunah remarkable as we host Mbaitoli USA convention; this breakthrough. makes me feel fulfilled. I must (President) Boston, Massachusetts begin by thanking the men and women who worked tirelessly to make it a success especially the entire 617 -721-9880 executive and board members. I am proud of you all. Sometimes, life is not about number but commitment and dedication of the few. Jude Iruka (Vice President) Atlanta, Georgia Mbaitoli New England started in 2005 and as the meeting progressed, we become aware of events back 770 -366-6012 home. My wife Mrs. Obidiya V. Dimunah said “this could be our key to peace and progress in Alphonso Mgbokwere Mbaitoli” (Udo N’Oganihu Mbaitoli). There was a remarkable demonstration of power of the people in (General Secretary) Mbaitoli during 2011 election in Imo State. We could continue to stay outside and look in or do Chicago, Illinois something about it. Some of us here tonight will recall that Mr. -

River Basins of Imo State for Sustainable Water Resources

nvironm E en l & ta i l iv E C n g Okoro et al., J Civil Environ Eng 2014, 4:1 f o i n l Journal of Civil & Environmental e a e n r r i DOI: 10.4172/2165-784X.1000134 n u g o J ISSN: 2165-784X Engineering Review Article Open Access River Basins of Imo State for Sustainable Water Resources Management BC Okoro1*, RA Uzoukwu2 and NM Chimezie2 1Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria 2Department of Civil Engineering Technology, Federal Polytechnic Nekede, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria Abstract The river basins of Imo state, Nigeria are presented as a natural vital resource for sustainable water resources management in the area. The study identified most of all the known rivers in Imo State and provided information like relief, topography and other geographical features of the major rivers which are crucial to aid water management for a sustainable water infrastructure in the communities of the watershed. The rivers and lakes are classified into five watersheds (river basins) such as Okigwe watershed, Mbaise / Mbano watershed, Orlu watershed, Oguta watershed and finally, Owerri watershed. The knowledge of the river basins in Imo State will help analyze the problems involved in water resources allocation and to provide guidance for the planning and management of water resources in the state for sustainable development. Keywords: Rivers; Basins/Watersheds; Water allocation; • What minimum reservoir capacity will be sufficient to assure Sustainability adequate water for irrigation or municipal water supply, during droughts? Introduction • How much quantity of water will become available at a reservoir An understanding of the hydrology of a region or state is paramount site, and when will it become available? In other words, what in the development of such region (state). -

Ndsp4 Legacy Book 2019 (Imo State)

NDSP4 & MPP9 WORKS PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION IN THE NINE NIGER DELTA STATES LEGACY BOOK EUROPEAN UNION (EU) NIGER DELTA SUPPORT PROGRAMME COMPONENT 4 (NDSP4) IN IMO STATE No 8, Barrister Obinna Okwara Crescent/Plot 37 Chief Executive Quarters, Opposite Ahiajoku Convention Centre. Area B, New Owerri, Imo State. IMO STATE EUROPEAN UNION NIGER DELTA SUPPORT PROGRAMME NDSP4 LEGACY BOOK 2019 IMO STATE MAP MBAITOLI ISIALA MBANO IDEATO SOUTH EUROPEAN UNION NIGER DELTA SUPPORT PROGRAMME NDSP4 LEGACY BOOK 2019 IMO STATE Publication: NDSP4/013/09/2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 PROGRAMME OVERVIEW 5 WORKS CONTRACT OVERVIEW 8 PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION TEAM 10 DETAILS OF NDSP4 PROGRAMME IN IMO STATE • STAKE HOLDERS TEAM 11 • PROJECT LIST 12 & 13 • PHOTOGRAPH OF IMPLEMENTED PROJECTS 14 Page 3 IMO STATE EUROPEAN UNION NIGER DELTA SUPPORT PROGRAMME NDSP4 LEGACY BOOK 2019 FOREWORD The NDSP4 Publication series is an attempt to bring some of our key reports and consultancy reports to our stakeholders and a wider audience. The overall objective of the Niger Delta Support Programme (NDSP) is to mitigate the conflict in the Niger Delta by addressing the main causes of the unrest and violence: bad governance, (youth) unemployment, poor delivery of basic services. A key focus of the programme will be to contribute to poverty alleviation through the development and support given to local community development initiatives. The NDSP4 aims to support institutional reforms and capacity building, resulting in Local Gov- ernment and State Authorities increasingly providing infrastructural services, income gener- ating options, sustainable livelihoods development, gender equity and community empow- erment. This will be achieved through offering models of transparency and participation as well as the involvement of Local Governments in funding Micro projects to enhance impact and sustainability. -

Spatial Appraisal of Problems and Prospects of Fertilizer Use for Agriculture on the Environment in Mbieri, Mbaitoli Local Government Area, Imo State Nigeria

International Journal of Physical and Human Geography Vol.5, No.2, pp.10-19, December 2017 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) SPATIAL APPRAISAL OF PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS OF FERTILIZER USE FOR AGRICULTURE ON THE ENVIRONMENT IN MBIERI, MBAITOLI LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA, IMO STATE NIGERIA. Chikwendu L.1 and Jenkwe E. D2 1 Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Imo State University, Owerri, Nigeria. 2 Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Abuja, Abuja, Nigeria. ABSTRACT: This study appraises the spatial problems and prospects of fertilizer use in agriculture on the Environment in Mbieri, Mbaitoli Local Government Area of Imo State. Structured questionnaires were sampled in the each villages randomly selected from the seven autonomous communities of Amaike-Mbieri, Awo Mbieri, Ezi-Mbieri, Ihitte Isi-Mbieri, Obazu Mbieri, Obi-Mbieri and Umueze-Mbieri for collection of data. The data were analysed using descriptive statistical tools of tables, charts and graphs. The outcome showed that 71.2% of the farmers do not have University Education. All the kinds of fertilizer in use in the study area contain Nitrogen with NPK 20-10-10 the most sought-after (35%). The major source of fertilizer in the study area is the open market while 54% of the farmers say they prefer the application of fertilizer NPK for replenishing lost soil nutrients. Finally, 60% of the Farmers in the study area use surface broadcast method in application of fertilizer NPK on their farms. However, some of this nitrogen compounds are washed down through surface runoffs causing pollution and eutrophication of the Ecosystems and water bodies. -

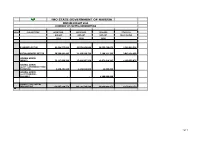

Imo State Government of Nigeria Revised Budget 2020 Summary of Capital Expenditure

IMO STATE GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA REVISED BUDGET 2020 SUMMARY OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE HEAD SUB-SECTORS APPROVED APPROVED REVISED COVID-19 BUDGET BUDGET BUDGET RESPONSIVE 2019 2020 2020 ECONOMIC SECTOR 82,439,555,839 63,576,043,808 20,555,468,871 2,186,094,528 SOCIAL SERVICES SECTOR 50,399,991,403 21,139,598,734 7,190,211,793 3,043,134,650 GENERAL ADMIN: (MDA'S) 72,117,999,396 17,421,907,270 12,971,619,207 1,150,599,075 GENERAL ADMIN: (GOVT COUNTERPART FUND PAYMENTS) 9,690,401,940 4,146,034,868 48,800,000 - GENERAL ADMIN: (GOVT TRANSFER - ISOPADEC) - - 4,200,000,000 - GRAND TOTAL CAPITAL EXPENDITURE 214,647,948,578 106,283,584,680 44,966,099,871 6,379,828,253 1of 1 IMO STATE GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA IMO STATE GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA REVISED BUDGET 2020 MINISTERIAL SUMMARY OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE ECONOMIC SECTOR APPROVED 2019 APPROVED 2020 REVISED 2020 COVID-19 RESPONSIVE O414 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY 1,499,486,000 2,939,000,000 1,150,450,000 - 0 AGRIC & FOOD SECURITY 1,499,486,000 0414-2 MINISTRY OF LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT 1,147,000,000 367,000,000 367,000,000 - 0 LIVESTOCK 1,147,000,000 697000000 1147000000 0414-1 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES 13,951,093,273 1,746,000,000 620,000,000 - 0 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT 13951093273 450000000 O415 MINISTRY OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY 7,070,700,000 2,650,625,077 1,063,000,000 - -5,541,800,000 MINISTRY OF COMMERCE, INDUSTRY AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP1528900000 0419-2 MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES 2,880,754,957 2,657,000,000 636,869,000 - 1,261,745,492 MINISTRY OF PUBLIC UTILITIES 4,142,500,449 -

And Resitivity Survey Methods for Evaluation of Groundwater Potentials: Case Study of Imo State, Nigeria

www.ccsenet.org/apr Applied Physics Research Vol. 3, No. 1; May 2011 Correlation of Self Potential (SP) and Resitivity Survey Methods for Evaluation of Groundwater Potentials: Case Study of Imo State, Nigeria Leonard I. Nwosu, Cyril N. Nwankwo & Anthony S. Ekine Department of Physics, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Received: September 21, 2010 Accepted: October 12, 2010 doi:10.5539/apr.v3n1p100 Abstract A total of seventeen vertical electric surroundings were carried out in Mbaitolu Local Government Area (L.G.A) of Imo State Nigeria, during which apparent resistivity and SP values were simultaneously measured. The field curves obtained reveals a multilayered earth with series of crest and trough for all the sounding stations. VES 6 showed only positive maxima and minima. The distribution of SP values for electrode spacing AB/2 = 100m divides the area into two zones of positive and negative potentials respectively. The anomaly high areas are those of favourable aquifer which form discharge zones with strong lateral flow and high aquifer thickness and transmissivity. Anomaly low areas correspond to areas of infiltration. The depth to aquifer determined from SP survey ranged from 40m to 115m and correlated fairly well with those obtained from resistivity result in 16 out of the 17 stations. The distribution of equipotential lines shown by the contour map divides the area into two zones by a zero potential line suggesting a possible ground water divided in terms of water quality or geologic setting or both. The cross-correlation coefficient computed statistically for each pair of depth points gave correlation significance at the 0.01 level, which validates the results. -

Environmental-And-Social-Impact-Assessment-For-The-Rehabilitation-And-Construction-Of

Public Disclosure Authorized FEDERAL REPUPLIC OF NIGERIA IMO STATE RURAL ACCESS AND MOBILITY PROJECT (RAMP-2) ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Public Disclosure Authorized FOR Public Disclosure Authorized THE REHABILITATION/ CONSTRUCTION OF 380.1KM OF RURAL ROADS IN IMO STATE August 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Final ESIA for the Rehabilitation of 88 Rural Roads in Imo State under RAMP-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................. vii LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................... viii LIST OF PLATES ............................................................................................................................. viii LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................... ix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Project Development Objective -

List of Member Banks

ABIA S/N Code Name FI Type Default group State Code State Description Local Gov CodeLocal Gov Description City Code City Description E-mail Phone Address 1 50005 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.08 Isuikwuato 904 Uturu [email protected] 08037731407, 08033062369 Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State 2 50085 Arochukwu Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.03 Arochukwu 180 Arochukwu [email protected] 08065062364, 08036001991 Amaikpe Square, Afor Arochukwu Market, Abia State. 3 51070 Bundi Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.02 Aba South 38 Aba [email protected] 8023409581 157, Cameroun Road, Aba, Abia State 4 50174 Chibueze Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.02 Aba South 38 Aba [email protected] O802228288, 08068588959, 08056620149 CKC, 82 Ehi/Asa Road, Aba, Abia State. 5 50230 Decency Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.16 Umuahia South [email protected] 08052103833, 080370314191 Afor Ibeji Market Square, Old Umuahia, Abia State. 6 50182 East-Gate Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.02 Aba South 38 Aba [email protected] 08034713691, 08037102981 135 Aba-Owerri Road, Aba, Abia State 7 50393 Hitech Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.02 Aba South 38 Aba [email protected] 143, Azikiwe Road, Aba, Abia State 8 50422 Ihechiowa Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.03 Arochukwu 180 Arochukwu [email protected] 07035544414, 08057465298, 08033147575 Umuye Ihechiowa, Arochukwu -

Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of Owerri, South East Nigeria

American Journal of Geographic Information System 2014, 3(1): 1-9 DOI: 10.5923/j.ajgis.20140301.01 Delineation and Characterization of Sub-catchments of Owerri, South East Nigeria, Using GIS Akajiaku C. Chukwuocha1,*, Joel I. Igbokwe2 1Department of Surveying and Geoinformatics, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria 2Department of Surveying and Geoinformatics, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka, Nigeria Abstract Catchment delineation and characterization are gaining increasing global attention as scientists seek better understanding of how runoff interacts with the landscape in the face of increasing flood devastations across the globe. All surface water flow systems occur in units of sub-catchments, the basic unit of landscape that drains its runoff through the same outlet to contribute to the main stream of the overall catchment. The delineation and characterization of sub-catchments would provide some basic data required for flood prediction, drainage design, water quality studies, erosion data, and sediment transport among others. In this study, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) were used to create a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of Owerri, South East Nigeria. The DEM was validated using Global Navigational Satellite Systems (GNSS) surveys. The DEM was processed through a number of steps in GIS to determine drainage routes with a minimum accumulation threshold. All cells that contribute into each stream were dissolved into a single unit of sub-catchment polygon and delineated. Characteristics of the sub-catchments including the average slope, the longest flow distance, the area and the centroid coordinates required for input in the Storm Water Management Model of the Environmental Protection Agency of U.S.A. -

LGA Aboh Mbaise Ahiazu Mbaise Ehime Mbano Ezinihitte Mbaise Ideato North Ideato South Ihitte Uboma Ikeduru Isiala Mbano Isu Mbai

LGA Aboh Mbaise Ahiazu Mbaise Ehime Mbano Ezinihitte Mbaise Ideato North Ideato South Ihitte Uboma Ikeduru Isiala Mbano Isu Mbaitoli Ngor Okpala Njaba Nkwerre Nwangele Obowo Oguta Ohaji/Egbema Okigwe Onuimo Orlu Orsu Oru East Oru West Owerri Municipal Owerri North Owerri West PVC PICKUP ADDRESS Inside The Local Govt. Secretariat Behind The Local Govt. Stadium Along Umuezela Isiala Mbano Road, Near Aba Branch Inside The Lga Secretariat Inside The Lga Secretariat Behind The Lga Office (SHARES A Common Fence With The Lga Office Along Isinweke Express Road Opposite The Lga Office Along Umuelemai/Umuezeala Road Along The Lga Office Road, Umundugba Along Awo-Mbieri Road, Nwaorieubi Inside The Lga Office Inside The Lga Office Along Nkwerre Orlu Road, Near The Lga Office Situated Within The Old Site Of The Lga Office Along Umuahia-Obowo Road, Opp. Obowo Police Station At Nkwo-Oguta Inside The Lga Secretariat Office Inside The Lga Complex Inside The Lga Office Along Ezerioha Road Along Police Station Road Awo-Idemili Insde The Lga Office Along Onitsha-Owerri Road, Mgbidi (AFTER Magistrate Court-Sharing Same Fence Opposite The State Post Office, Along Douglas Road, Within The Lga Secretariat After The Lga H/Q (ORIE Uratta) Within The Lga Office Along Onitsha-Owerri Road, Mgbidi (AFTER Magistrate Court-Sharing Same Fence Opposite The State Post Office, Along Douglas Road, Within The Lga Secretariat. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Radionuclide Contents in Yam Samples and Health Risks Assessment in Oguta Oil Producing Locality Imo State Nigeria

I J P R A INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF 2766-2748 PHYSICS RESEARCH AND APPLICATIONS Research Article More Information *Address for Correspondence: Benedict Chukwudi Eke, Department of Physics, Radionuclide contents in yam University of Ibadan, Nigeria, Email: [email protected] samples and health risks Submitted: January 21, 2021 Approved: April 03, 2021 assessment in Oguta oil producing Published: April 05, 2021 How to cite this article: Jibiri NN, Eke BC. Radionuclide contents in yam samples and health locality Imo State Nigeria risks assessment in Oguta oil producing locality Imo State Nigeria. Int J Phys Res Appl. 2021; 4: Nnamdi Norbert Jibiri1 and Benedict Chukwudi Eke2* 006-014. DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijpra.1001034 1Department of Physics, University of Ibadan, Nigeria Copyright: © 2021 Jibiri NN, et al. This is 2 Department of Physics, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and re- Abstract production in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Oguta LGA is surrounded by 44 oil wells located around diff erent communities. Preliminary Keywords: Natural radionuclides; Yam samples; investigations indicated that crude wastes were not properly managed and oil spillage occurred Radiological parameters; Health risks regularly in the LGA. Therefore, assessment of both radionuclide contents in yam matrix and health risks in Oguta was carried out to determine possible radiological health risks associated with improper management of crude wastes, and also evaluate haematological health profi le in the LGA for future reference and research. A well calibrated NaI (Tl) detector was deployed for the radiological investigation, and about 5 ml of blood samples were collected from 190 OPEN ACCESS participants each from Oguta and the control LGAs for haematological assessment.