Colours of Minor Bodies in the Outer Solar System II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy

Barucci et al.: Surface Characteristics of TNOs and Centaurs 647 Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy M. A. Barucci and A. Doressoundiram Observatoire de Paris D. P. Cruikshank NASA Ames Research Center The external region of the solar system contains a vast population of small icy bodies, be- lieved to be remnants from the accretion of the planets. The transneptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs (located between Jupiter and Neptune) are probably made of the most primitive and thermally unprocessed materials of the known solar system. Although the study of these objects has rapidly evolved in the past few years, especially from dynamical and theoretical points of view, studies of the physical and chemical properties of the TNO population are still limited by the faintness of these objects. The basic properties of these objects, including infor- mation on their dimensions and rotation periods, are presented, with emphasis on their diver- sity and the possible characteristics of their surfaces. 1. INTRODUCTION cally with even the largest telescopes. The physical char- acteristics of Centaurs and TNOs are still in a rather early Transneptunian objects (TNOs), also known as Kuiper stage of investigation. Advances in instrumentation on tele- belt objects (KBOs) and Edgeworth-Kuiper belt objects scopes of 6- to 10-m aperture have enabled spectroscopic (EKBOs), are presumed to be remnants of the solar nebula studies of an increasing number of these objects, and signifi- that have survived over the age of the solar system. The cant progress is slowly being made. connection of the short-period comets (P < 200 yr) of low We describe here photometric and spectroscopic studies orbital inclination and the transneptunian population of pri- of TNOs and the emerging results. -

The Dynamics of Plutinos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The dynamics of Plutinos Qingjuan Yu and Scott Tremaine Princeton University Observatory, Peyton Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544-1001, USA ABSTRACT Plutinos are Kuiper-belt objects that share the 3:2 Neptune resonance with Pluto. The long-term stability of Plutino orbits depends on their eccentric- ity. Plutinos with eccentricities close to Pluto (fractional eccentricity difference < ∆e=ep = e ep =ep 0:1) can be stable because the longitude difference librates, | − | ∼ in a manner similar to the tadpole and horseshoe libration in coorbital satellites. > Plutinos with ∆e=ep 0:3 can also be stable; the longitude difference circulates ∼ and close encounters are possible, but the effects of Pluto are weak because the encounter velocity is high. Orbits with intermediate eccentricity differences are likely to be unstable over the age of the solar system, in the sense that encoun- ters with Pluto drive them out of the 3:2 Neptune resonance and thus into close encounters with Neptune. This mechanism may be a source of Jupiter-family comets. Subject headings: planets and satellites: Pluto — Kuiper Belt, Oort cloud — celestial mechanics, stellar dynamics 1. Introduction The orbit of Pluto has a number of unusual features. It has the highest eccentricity (ep =0:253) and inclination (ip =17:1◦) of any planet in the solar system. It crosses Neptune’s orbit and hence is susceptible to strong perturbations during close encounters with that planet. However, close encounters do not occur because Pluto is locked into a 3:2 orbital resonance with Neptune, which ensures that conjunctions occur near Pluto’s aphelion (Cohen & Hubbard 1965). -

![Arxiv:2102.05076V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 17 Feb 2021 Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6911/arxiv-2102-05076v2-astro-ph-ep-17-feb-2021-et-al-226911.webp)

Arxiv:2102.05076V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 17 Feb 2021 Et Al

Draft version August 30, 2021 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX63 The Reflectance of Cold Classical Trans-Neptunian Objects in the Nearest Infrared Tom Seccull,1, 2 Wesley C. Fraser,3 and Thomas H. Puzia4 1Gemini Observatory/NSF's NOIRLab, 670 N. A'ohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720, USA 2Astrophysics Research Centre, Queen's University Belfast, University Road, Belfast, BT7 1NN, UK 3Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, 5071 West Saanich Road, Victoria, BC V9E 2E7, Canada 4Institute of Astrophysics, Pontificia Universidad Cat´olica de Chile, Av. Vicu~naMacKenna 4860, 7820436, Santiago, Chile (Received 2020 Nov 8; Revised 2021 Jan 22; Accepted 2021 Feb 6) Submitted to PSJ ABSTRACT Recent photometric surveys of Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) have revealed that the cold classical TNOs have distinct z-band color characteristics, and occupy their own distinct surface class. This suggested the presence of an absorption band in the reflectance spectra of cold classicals at λ > 0:8 µm. Here we present reflectance spectra spanning 0:55 − 1:0 µm for six TNOs occupying dynamically cold orbits at a ∼ 44 au. Five of our spectra show a clear and broadly consistent reduction in spectral gradient above 0:8 µm that diverges from their linear red optical continuum and agrees with their reported photometric colour data. Despite predictions, we find no evidence that the spectral flattening is caused by an absorption band centered near 1:0 µm. We predict that the overall consistent shape of these five spectra is related to the presence of similar refractory organics on each of their surfaces, and/or their similar physical surface properties such as porosity or grain size distribution. -

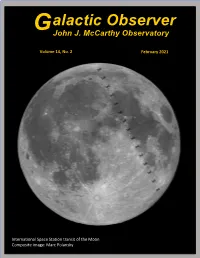

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

Download the PDF Preprint

Five New and Three Improved Mutual Orbits of Transneptunian Binaries W.M. Grundya, K.S. Nollb, F. Nimmoc, H.G. Roea, M.W. Buied, S.B. Portera, S.D. Benecchie,f, D.C. Stephensg, H.F. Levisond, and J.A. Stansberryh a. Lowell Observatory, 1400 W. Mars Hill Rd., Flagstaff AZ 86001. b. Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Dr., Baltimore MD 21218. c. Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz CA 95064. d. Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut St. #300, Boulder CO 80302. e. Planetary Science Institute, 1700 E. Fort Lowell, Suite 106, Tucson AZ 85719. f. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, 5241 Broad Branch Rd. NW, Washington DC 20015. g. Dept. of Physics and Astronomy, Brigham Young University, N283 ESC Provo UT 84602. h. Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 N. Cherry Ave., Tucson AZ 85721. — Published in 2011: Icarus 213, 678-692. — doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.03.012 ABSTRACT We present three improved and five new mutual orbits of transneptunian binary systems (58534) Logos-Zoe, (66652) Borasisi-Pabu, (88611) Teharonhiawako-Sawiskera, (123509) 2000 WK183, (149780) Altjira, 2001 QY297, 2003 QW111, and 2003 QY90 based on Hubble Space Tele- scope and Keck II laser guide star adaptive optics observations. Combining the five new orbit solutions with 17 previously known orbits yields a sample of 22 mutual orbits for which the period P, semimajor axis a, and eccentricity e have been determined. These orbits have mutual periods ranging from 5 to over 800 days, semimajor axes ranging from 1,600 to 37,000 km, ec- centricities ranging from 0 to 0.8, and system masses ranging from 2 × 1017 to 2 × 1022 kg. -

Thermal Measurements

Physical characterization of Kuiper belt objects from stellar occultations and thermal measurements Pablo Santos-Sanz & the SBNAF team [email protected] Stellar occultations Simple method to: -Obtain high precision sizes/shapes (unc. ~km) -Detect/characterize atmospheres/rings… -Obtain albedo, density… -Improve the orbit of the body …this looks like very nice but...the reality is harder (at least for TNOs and Centaurs) EPSC2017, Riga, Latvia, 20 Sep. 2017 Stellar occultations Titan 10 mas Quaoar 0.033 arsec Diameter of 1 Euro (33 mas) Pluto coin at 140 km Eris Charon Makemake Pablo Santos-Sanz EPSC2017, Riga, Latvia, 20 Sep. 2017 Stellar occultations ~25 occultations by 15 TNOs (+ Pluto/Charon + Chariklo + Chiron + 2002 GZ32) Namaka Dysnomia Ixion Hi’iaka Pluto Haumea Eris Chiron 2007 UK126 Chariklo Vanth 2014 MU69 2002 GZ32 2003 VS2 2002 KX14 2002 TX300 2003 AZ84 2005 TV189 Stellar occultations: Eris & Chariklo Eris: 6 November 2010 Chariklo: 3 June 2014 • Size ~ Plutón • It has rings! • Albedo= 96% 3 • Density= 2.5 g/cm Danish 1.54-m telescope (La Silla) • Atmosphere < 1nbar (10-4 x Pluto) Eris’ radius Pluto’s radius 1163±6 km 1188.3±1.6 km (Nimmo et al. 2016) Braga-Ribas et al. 2014 (Nature) Sicardy et al. 2011 (Nature) EPSC2017, Riga, Latvia, 20 Sep. 2017 Stellar occultations: Makemake 23 April 2011 Geometric Albedo = 77% (betwen Pluto and Eris) Possible local atmosphere! Ortiz et al. 2012 (Nature) EPSC2017, Riga, Latvia, 20 Sep. 2017 Stellar occultations: latest “catches” 2007 UK : 15 November 2014 2003 AZ84: 8 Jan. 2011 single, 3 Feb. 126 2012 multi, 2 Dec. -

Distant Ekos: 2012 BX85 and 4 New Centaur/SDO Discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG

Issue No. 79 February 2012 r ✤✜ s ✓✏ DISTANT EKO ❞✐ ✒✑ The Kuiper Belt Electronic Newsletter ✣✢ Edited by: Joel Wm. Parker [email protected] www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews CONTENTS News & Announcements ................................. 2 Abstracts of 8 Accepted Papers ......................... 3 Newsletter Information .............................. .....9 1 NEWS & ANNOUNCEMENTS There was 1 new TNO discovery announced since the previous issue of Distant EKOs: 2012 BX85 and 4 new Centaur/SDO discoveries: 2000 GQ148, 2012 BR61, 2012 CE17, 2012 CG Objects recently assigned numbers: 2010 EP65 = (312645) 2008 QD4 = (315898) 2010 EN65 = (316179) 2008 AP129 = (315530) Objects recently assigned names: 1997 CS29 = Sila-Nunam Current number of TNOs: 1249 (including Pluto) Current number of Centaurs/SDOs: 337 Current number of Neptune Trojans: 8 Out of a total of 1594 objects: 644 have measurements from only one opposition 624 of those have had no measurements for more than a year 316 of those have arcs shorter than 10 days (for more details, see: http://www.boulder.swri.edu/ekonews/objects/recov_stats.jpg) 2 PAPERS ACCEPTED TO JOURNALS The Dynamical Evolution of Dwarf Planet (136108) Haumea’s Collisional Family: General Properties and Implications for the Trans-Neptunian Belt Patryk Sofia Lykawka1, Jonathan Horner2, Tadashi Mukai3 and Akiko M. Nakamura3 1 Astronomy Group, Faculty of Social and Natural Sciences, Kinki University, Japan 2 Department of Astrophysics, School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Australia 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Kobe University, Japan Recently, the first collisional family was identified in the trans-Neptunian belt (otherwise known as the Edgeworth-Kuiper belt), providing direct evidence of the importance of collisions between trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). -

Journal Pre-Proof

Journal Pre-proof A statistical review of light curves and the prevalence of contact binaries in the Kuiper Belt Mark R. Showalter, Susan D. Benecchi, Marc W. Buie, William M. Grundy, James T. Keane, Carey M. Lisse, Cathy B. Olkin, Simon B. Porter, Stuart J. Robbins, Kelsi N. Singer, Anne J. Verbiscer, Harold A. Weaver, Amanda M. Zangari, Douglas P. Hamilton, David E. Kaufmann, Tod R. Lauer, D.S. Mehoke, T.S. Mehoke, J.R. Spencer, H.B. Throop, J.W. Parker, S. Alan Stern, the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics, and Imaging Team PII: S0019-1035(20)30444-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114098 Reference: YICAR 114098 To appear in: Icarus Received date: 25 November 2019 Revised date: 30 August 2020 Accepted date: 1 September 2020 Please cite this article as: M.R. Showalter, S.D. Benecchi, M.W. Buie, et al., A statistical review of light curves and the prevalence of contact binaries in the Kuiper Belt, Icarus (2020), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114098 This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. -

Precision Astrometry for Fundamental Physics – Gaia

Gravitation astrometric tests in the external Solar System: the QVADIS collaboration goals M. Gai, A. Vecchiato Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica [INAF] Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino [OATo] WAG 2015 M. Gai - INAF-OATo - QVADIS 1 High precision astrometry as a tool for Fundamental Physics Micro-arcsec astrometry: Current precision goals of astrometric infrastructures: a few 10 µas, down to a few µas 1 arcsec (1) 5 µrad 1 micro-arcsec (1 µas) 5 prad Reference cases: • Gaia – space – visible range • VLTI – ground – near infrared range • VLBI – ground – radio range WAG 2015 M. Gai - INAF-OATo - QVADIS 2 ESA mission – launched Dec. 19th, 2013 Expected precision on individual bright stars: 1030 µas WAG 2015 M. Gai - INAF-OATo - QVADIS 3 Spacetime curvature around massive objects 1.5 G: Newton’s 1".74 at Solar limb 8.4 rad gravitational constant GM 1 cos d: distance Sun- 1 1 observer c2d 1 cos M: solar mass 0.5 c: speed of light Deflection [arcsec] angle : angular distance of the source to the Sun 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Distance from Sun centre [degs] Light deflection Apparent variation of star position, related to the gravitational field of the Sun ASTROMETRY WAG 2015 M. Gai - INAF-OATo - QVADIS 4 Precision astrometry for Fundamental Physics – Gaia WAG 2015 M. Gai - INAF-OATo - QVADIS 5 Precision astrometry for Fundamental Physics – AGP Talk A = Apparent star position measurement AGP: G = Testing gravitation in the solar system Astrometric 1) Light deflection close to the Sun Gravitation 2) High precision dynamics in Solar System Probe P = Medium size space mission - ESA M4 (2014) Design driver: light bending around the Sun @ μas fraction WAG 2015 M. -

1 Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects

Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects - a Review Renu Malhotra Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Email: [email protected] Abstract Our understanding of the history of the solar system has undergone a revolution in recent years, owing to new theoretical insights into the origin of Pluto and the discovery of the Kuiper belt and its rich dynamical structure. The emerging picture of dramatic orbital migration of the planets driven by interaction with the primordial Kuiper belt is thought to have produced the final solar system architecture that we live in today. This paper gives a brief summary of this new view of our solar system's history, and reviews the astronomical evidence in the resonant populations of the Kuiper belt. Introduction Lying at the edge of the visible solar system, observational confirmation of the existence of the Kuiper belt came approximately a quarter-century ago with the discovery of the distant minor planet (15760) Albion (formerly 1992 QB1, Jewitt & Luu 1993). With the clarity of hindsight, we now recognize that Pluto was the first discovered member of the Kuiper belt. The current census of the Kuiper belt includes more than 2000 minor planets at heliocentric distances between ~30 au and ~50 au. Their orbital distribution reveals a rich dynamical structure shaped by the gravitational perturbations of the giant planets, particularly Neptune. Theoretical analysis of these structures has revealed a remarkable dynamic history of the solar system. The story is as follows (see Fernandez & Ip 1984, Malhotra 1993, Malhotra 1995, Fernandez & Ip 1996, and many subsequent works). -

Download This Article in PDF Format

A&A 564, A35 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322416 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics “TNOs are Cool”: A survey of the trans-Neptunian region X. Analysis of classical Kuiper belt objects from Herschel and Spitzer observations E. Vilenius1,C.Kiss2, T. Müller1, M. Mommert3,4, P. Santos-Sanz5,6,A.Pál2, J. Stansberry7, M. Mueller8,9, N. Peixinho10,11,E.Lellouch6, S. Fornasier6,12, A. Delsanti6,13, A. Thirouin5, J. L. Ortiz5,R.Duffard5, D. Perna6, and F. Henry6 1 Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Postfach 1312, Giessenbachstr., 85741 Garching, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 2 Konkoly Observatory, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Konkoly Thege 15-17, 1121 Budapest, Hungary 3 Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V., Institute of Planetary Research, Rutherfordstr. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany 4 Northern Arizona University, Department of Physics and Astronomy, PO Box 6010, Flagstaff AZ 86011, USA 5 Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (CSIC), Glorieta de la Astronomía s/n, 18008-Granada, Spain 6 LESIA-Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC Univ. Paris 06, Univ. Paris-Diderot, France 7 Stewart Observatory, The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85721, USA 8 SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Postbus 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands 9 UNS-CNRS-Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, Laboratoire Cassiopée, BP 4229, 06304 Nice Cedex 04, France 10 Center for Geophysics of the University of Coimbra, Geophysical and Astronomical Observatory of the University of Coimbra, Almas de Freire, 3040-004 Coimbra, Portugal 11 Unidad de Astronomía, Facultad de Ciencias Básicas, Universidad de Antofagasta, 601 avenida Angamos, Antofagasta, Chile 12 Univ. -

University of Hawai'i Library

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY A Physical Survey of Centaurs A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ASTRONOMY MAY 2003 By James M. Bauer Dissertation Committee: Karen J. Meech, Chairperson Tom Dinell Alan Stockton David J. Tholen Alan Tokunaga © Copyright 2003 by James M. Bauer All Rights Reserved iii To my wife, Chija "Oh, night that was my guide, Oh, night more lovely than the rising Sun... " IV Acknowledgements I wish to thank my dissertation committee, especially the chair, my graduate adviser and exceptionally generous and tolerant mentor, Karen J. Meech, but also Alan 'Ibkunaga, Dave Tholen, Alan Stockton and Tom Dinel!. Much needed advice and direction was contributed by all the members ofmy committee, and I will ever feel an abundance of respect, friendship, and gratitude toward each member. Yan Fernandez generously provided much additional guidance which was indispensable, to say the least. Likewise, Tobias Owen very graciously contributed many hours and imparted much wisdom to this work. I'd like to thank Ted Roush, for his instruction on the use and administration of his Hapke scattering code, and his advice in the interpretation of spectra, and above all his patience with a slow, but determined student. Though not officially committee members, Drs. Fernandez, Roush, and Owen were as integral a part of the writing of this dissertation as the committee members. John Kormendy and Mike Delisio, who were originally part of the committee, but later left for positions out of state also deserve and have my gratitude.