THE GEOPOLITICS of the SUNNI-SHI„I DIVIDE in the MIDDLE EAST by Samuel Helfont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Privacy As Privilege: the Stored Communications Act and Internet Evidence Contents

PRIVACY AS PRIVILEGE: THE STORED COMMUNICATIONS ACT AND INTERNET EVIDENCE Rebecca Wexler CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2723 I. THE INTERNET AND THE TELEGRAPH ....................................................................... 2730 A. The Puzzle ........................................................................................................................ 2731 B. The Stored Communications Act .................................................................................. 2735 C. Telegraph Privacy Statutes ............................................................................................. 2741 II. PRIVACY AS PRIVILEGE .................................................................................................... 2745 A. Statutory Privileges ........................................................................................................ 2745 1. Defining Statutory Privileges ................................................................................... 2745 2. Common Features of Privileges ............................................................................... 2748 3. Confidentiality Without Privilege ........................................................................... 2750 4. The Current Stored Communications Act Privilege ............................................. 2753 B. The Rules that Govern Statutory Privilege Construction ......................................... -

Expression of Concern Barry Falls F Or the Washing T on Pos

VOLUME 19 ISSUE 1 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program Expression of Concern T ON POS T OR THE WASHING F BARRY FALLS ■ Post Reprint: “Our indifference toward kids is unconscionable” ■ Post Reprint: “Words Fail: How do we talk about what’s happening to our planet?” ■ Student Activity: Find the Right Keener Word ■ Post Reprint: “A graphic photo gives the press pause” ■ Post Reprint: “‘This will be catastrophic’: Maine families face elder boom, worker shortage in preview of nation’s future” ■ Student Activity: A Shortage of Young Workers ■ Post Appreciation Reprint: “The Tenacity of Hope” September 10, 2019 ©2019 THE WASHINGTON POST VOLUME 19 ISSUE 1 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program IN TRO DUC TION. When you think of three months in your life, you may be quite surprised by the number of new and unexpected activities that get mixed in with the mundane and routine. Imagine having events and issues in your community, your state, country and the world to record in your diary. Reprints and activities in this guide cover June-August 2019. Petula Dvorak looks at recent events, discerns a theme and shares with her readers. Together the examples serve as a reminder of what took place in one week and ask adults to consider their responsibilities. What would your students have to say about them? In addition to looking at the words we use (“Words Fail”) and the photographs we print (“A graphic photo The gives the press pause”), we take time to appreciate a great American author. -

A National Strategy for Synthetic Biology Lt Col Marcus A

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - PERSPECTIVE A National Strategy for Synthetic Biology LT COL MARCUS A. CUNNINGHAM, USAF JOHN P. GEIS II Abstract We are experiencing a technical revolution in biotechnology that will change the way we live as much as any technological advance in human history.1 Advances in gene sequencing, gene editing, and gene synthesis have shifted our relationship with the building blocks of life. This new science, synthetic biology, is in its early stages but has already created dis- tinct threats and opportunities in US national security. It promises ad- vances in materials science, manufacturing, logistics, sensor technology, medicine, health care, and human augmentation while simultaneously increasing the possibility and severity of man-made pandemics through unintended consequences in genetic experiments or improved bioweap- ons. This article proposes a National Strategy for Synthetic Biology (NSSB) to defend the homeland and promote American strength by building security into synthetic biology and by making synthetic biology an investment priority. The United States can achieve greater security by regulating and controlling synthetic biology to prevent unintended conse- quences while investing in people and industries to maintain a security advantage in the field. ***** uturist Klaus Schwab predicts in his book The Fourth Industrial Revolution “a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work, and relate to one another. In its scale, scope, Fand complexity, the transformation will be unlike anything humankind has experienced.” This revolution builds on the Third Revolution based on electronics and information technology to blur “the lines between the physical, digital, and biological spheres.”2 Scientists have begun to use the term “synthetic biology” to describe the blurring of those lines by the con- vergence of genetic technologies powered by digital tools and engineer- ing principles to create new physical substances and chemicals. -

William Weaver

William Weaver Center for Law and Border Studies 108 Miners’ Hall University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX 79968 Office: 915.747.8867 Fax: 915.747.6105 [email protected] CURRENT POSITIONS Director Center for Law and Border Studies College of Liberal Arts University of Texas at El Paso Professor College of Liberal Arts University of Texas at El Paso EDUCATION Ph.D. in Politics (August, 1993) Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics University of Virginia Comprehensive subfields: Public Law; International Law and Organizations; Modern Political Thought; Ancient Political Thought J.D. (May, 1992) School of Law University of Virginia Editorial Board of Virginia Law Review M.A. in Politics (January, 1989) Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics University of Virginia B.A. in Government (January, 1987) Earl Warren Graduate in Government California State University, Sacramento RESEARCH BOOKS In Progress: William G. Weaver and Sibel Edmonds, Shooting the Messenger: Whistleblowers, National Security, and the Law. William G. Weaver and Brent McCune, Bureaucracy that Kills. 1 Completed: Robert M. Pallitto and William G. Weaver, Presidential Secrecy and the Law, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007). Kathleen Staudt and William G. Weaver, Feminisms and Political Science: Integration or Transformation? (New York: MacMillan/Twayne Press, 1997). Lief Carter, Austin Sarat, Mark Silverstein, and William G. Weaver, New Perspectives on American Law: An Introduction to Private Law and Politics and Society (Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press, 1997). Sections on torts and property; approximately forty percent of the book. EDITED VOLUMES M.E. Brint and William G. Weaver, eds., Pragmatism in Law and Society, a volume in the Stanford Series on Law and Society (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1991). -

Witness Qualifications

Curriculum Vitae Jeffrey Stein, LPI, BAI, CII, CCDI, V.S.M. 882 S. Matlack St. Suite 206 West Chester, PA 19382 610-696-7799 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Jeffrey Stein has 30+ years of experience in the private investigations, security, security consulting, CCTV and loss prevention fields. He is the President / Owner of ELPS Private Detective Agency who provides investigative and security services to attorneys, businesses, cannabis industry and private citizens. Stein has personally conducted over three thousand internal and external integrity and witness interviews during the course of his career in the private sector for both civil and criminal cases. He is a licensed Professional Investigator in both New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Stein is also the President and owner of PA Digital Surveillance Systems, with over 33 years’ in-depth CCTV experience; “Hands on” to senior executive levels. His experience and expertise with CCTV and motion detection analysis is derived from formal training, education, and years of hands experience to arrive at his opinions. In depth analysis, frame by frame, is often pivotal in many civil and criminal cases. Stein received his Bachelor of Arts Degree in Criminal Justice from West Chester University. He has received advanced training in interviewing and interrogation techniques and attended the New Jersey State Police Academy, Municipal Class, located in Sea Girt, NJ. He is also Board Certified as a Criminal Defense Investigator by the Criminal Defense Investigation Training Council and a Board Accredited Investigator. His expertise, while specializing in criminal defense / homicide investigations, includes personal injury, inadequate security, liquor liability, corporate fraud, white collar crime, workplace violence, civil investigations and surveillance systems. -

Here Is the Original NPF Newsboy

AWARDS CEREMONY, 5:30 P.M. EST FOLLOWING THE AWARDS CEREMONY Sol Taishoff Award for Excellence in Broadcast Journalism: Audie Cornish, National Public Radio Panel discussion on the state of journalism today: George Will, Audie Cornish and Peter Bhatia with moderator Dana Bash of CNN. Presented by Adam Sharp, President and CEO of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Breakout sessions, 6:20 p.m.: Innovative Storytelling Award: Jonah Kessel and Hiroko Tabuchi, The New York Times · Minneapolis Star Tribune cartoonist Steve Sack, joined by last year’s Berryman winner, Presented by Heather Dahl, CEO, Indicio.tech RJ Matson. Honorable mention winner Ruben Bolling will join. PROGRAM TONIGHT’S Clifford K. & James T. Berryman Award for Editorial Cartoons: Steve Sack, Minneapolis Star Tribune · Time magazine’s Molly Ball, interviewed about her coverage of House Speaker Nancy Presented by Kevin Goldberg, Vice President, Legal, Digital Media Association Pelosi by Terence Samuel, managing editor of NPR. Honorable mention winner Chris Marquette of CQ Roll Call will speak about his work covering the Capitol Police. Benjamin C. Bradlee Editor of the Year Award: Peter Bhatia, Detroit Free Press · USA Today’s Brett Murphy and Letitia Stein will speak about the failures and future of Presented by Susan Swain, Co-President and CEO, C-SPAN the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, moderated by Elisabeth Rosenthal, editor- in-chief of Kaiser Health News. Everett McKinley Dirksen Award for Distinguished Reporting of Congress: Molly Ball, Time · The Washington Post’s David J. Lynch, Josh Dawsey, Jeff Stein and Carol Leonnig will Presented by Cissy Baker, Granddaughter of Senator Dirksen talk trade, moderated by Mark Hamrick of Bankrate.com. -

Biden Endures 1St Cabinet Defeat As Tanden Withdraws

A18 EZ RE the washington post . wednesday, march 3, 2021 Biden endures 1st Cabinet defeat as Tanden withdraws Tanden from A1 job. Tanden had called Collins “the Tanden is “incredibly grateful worst” and “pathetic,” and said for your leadership on behalf of “vampires have more heart than the American people and for your Ted Cruz,” referring to the GOP agenda that will make such a senator from Texas. Tanden has transformative difference in peo- compared Senate Minority Lead- ple’s lives,” she told Biden. er Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) to Her nomination began to col- “Voldemort,” the Harry Potter lapse last month when Sen. Joe series villain, and called him Manchin III (D-W.Va.) said he “Moscow Mitch.” would oppose Tanden for the In turn, Republican senators post, citing her past remarks faced accusations of a double targeting Republicans. That standard when it came to Tanden meant she would need at least and her Twitter posts, consider- one Republican vote to be con- ing how often they feigned igno- firmed in the 50-50 Senate, but rance about President Donald potential swing votes including Trump’s social media feeds dur- Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine) ing his administration. Trump and Mitt Romney (R-Utah) also regularly aimed furious insults at said they would not back her. an array of people who angered Tanden, a veteran political op- him, including foreign leaders erative who most recently led the and Democratic lawmakers. liberal Washington-based Center In recent days, attention had for American Progress think largely turned to Sen. Lisa Mur- Andrew Harnik/Pool/Associated press tank, had maintained an active kowski (R-Alaska), who has been Neera Tanden withdrew on Tuesday from consideration for the role of White House budget director after facing opposition over her past presence on Twitter, frequently weighing whether to support sharp criticism of Republican senators on social media. -

Top Five Reasons Sanders Is Selling out His Supporters

Top Five Reasons Sanders Supporters Will Never Be Excited About Hillary Clinton SANDERS: CLINTON HAS BACKED “VIRTUALLY EVERY TRADE AGREEMENT THAT HAS COST THE WORKERS OF THIS COUNTRY MILLIONS OF JOBS” Sanders Stance On Trade Stands In Stark Contrast To The Radical, Corporate Globalist Agenda That Clinton Represents As She Refuses To Disavow TPP Sanders Has Criticized Clinton For Voting “For Virtually Every Trade Agreement That Has Cost The Workers Of This Country Millions Of Jobs.” NBC POLITICAL DIRECTOR CHUCK TODD: “So you believe she doesn't have the judgment to be president of the United States?” SANDERS: “Well, when you vote for virtually every trade agreement that has cost the workers of this country millions of jobs, when you support and continue to support fracking, despite the crisis that we have in terms of clean water, and essentially, when you have a super PAC that is raising tens of millions of dollars from every special interest out there, including 15 million from Wall Street, the American people do not believe that that is the kind of president that we need to make the changes in America to protect the working families of this country.” (NBC’s “Meet The Press,” 4/10/16) Sanders’ Campaign Called Clinton A Potential “Outsourcer-In Chief,” Saying She “Has Been A Consistent Advocate Of The Job-Killing Trade Deals” That Have Lost “Almost 5 Million Manufacturing Jobs Over The Last 15 Years.” “At a rally on Wednesday former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton told those gathered, ‘Don’t let anybody tell you we can’t make anything in America anymore.’ What she failed to tell the audience is that she has been a consistent advocate of the job-killing trade deals that have contributed to the loss of nearly 60,000 factories in the United States and almost 5 million manufacturing jobs over the last 15 years.” (Press Release, “Hillary Clinton: Outsourcer-In-Chief,” Bernie 2016, 3/3/16) Sanders Has Attacked Clinton For Being “Very Reluctant To Come Out In Opposition” To The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). -

America's Alleged Intelligence Failure in The

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2017 America’s Alleged Intelligence Failure in the Prelude to Operation Iraqi Freedom: A Study of Analytic Factors Cake, Timothy Cake, T. (2017). America’s Alleged Intelligence Failure in the Prelude to Operation Iraqi Freedom: A Study of Analytic Factors (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/24784 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3688 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY America’s Alleged Intelligence Failure in the Prelude to Operation Iraqi Freedom: A Study of Analytic Factors by Timothy Cake A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MILITARY, SECURITY, AND STRATEGIC STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2017 © Timothy Cake 2017 ABSTRACT In the prelude to Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), notables in the G. W. Bush administration declared Iraq to be an existential threat as it had weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and connections to transnational terrorist groups. After the 2003 invasion of that state, coalition forces engaged in a search effort that found no significant evidence of WMD. -

Space Pirates, Geosynchronous Guerrillas, and Nonterrestrial Terrorists Nonstate Threats in Space Gregory D

FEATURE Space Pirates, Geosynchronous Guerrillas, and Nonterrestrial Terrorists Nonstate Threats in Space GREGORY D. MILLER, PHD Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be repro- duced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. One of the policy implications of the second space age is that the availability of advanced space capabilities on the commercial market can potentially bring the advantages of space within the reach of rogue nations and non- state actors. —Todd Harrison, Zack Cooper, Kaitlyn Johnson, and Thomas Roberts “Escalation and Deterrence in the Second Space Age” Center for Strategic and International Studies resident Donald J. Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS) posits the return of great- power competition, particularly calling out Russia and China as rivals, and highlights the need to reemphasize space both for de- Pfense and commerce.1 Shortly after the publication of the NSS, the president called for the creation of a Space Force, at least partly to defend US security and eco- nomic interests in space, and then directed the Pentagon to create a Space Force with his signing of Space Policy Directive-4 on 19 February 2019.2 China and Russia continue to develop a range of antispace capabilities, includ- ing computer viruses, jamming, lasers, and antisatellite missiles. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 166 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2020 No. 24 Senate The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was PRESCRIPTION DRUG COSTS As a number of my Republican col- called to order by the President pro Mr. GRASSLEY. Last night, in the leagues have confessed, the House man- tempore (Mr. GRASSLEY). State of the Union Address, President agers have proven their case. President f Trump called on Congress to put bipar- Trump did sanction a corrupt con- spiracy to smear a political opponent, PRAYER tisan legislation to lower prescription drug prices on his desk and that he former Vice President Joe Biden. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- would sign it. President Trump assigned Rudy fered the following prayer: Here are the facts. The House is con- Giuliani, his personal lawyer, to ac- Let us pray. trolled by Democrats. The Senate re- complish that goal by arranging sham Strong Deliverer, our shelter in the quires bipartisanship to get any legis- investigations by the Government of time of storms, we acknowledge today lating done. There are only a couple of Ukraine. President Trump advanced that You are God and we are not. You months left before the campaign season his corrupt scheme by instructing the don’t disappoint those who trust in will likely impede anything from being three amigos—Ambassador Volker, You, for You are our fortress and bul- accomplished in this Congress. -

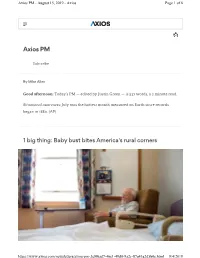

Axios PM - August 15, 2019 - Axios Page 1 of 6

Axios PM - August 15, 2019 - Axios Page 1 of 6 Axios PM Subscribe By Mike Allen Good afternoon: Today's PM — edited by Justin Green — is 537 words, a 2 minute read. Situational awareness: July was the hottest month measured on Earth since records began in 1880. (AP) 1 big thing: Baby bust bites America's rural corners https://www.axios.com/newsletters/axios-pm-3e9f6ad7-46e1-49d0-9a2c-87a43a2d5b0e.html 9/4/2019 Axios PM - August 15, 2019 - Axios Page 2 of 6 James Lagasse, 84, watches a nursing home employee make his bed in Dover-Foxcroft, Maine. Photo: Marlena Sloss/The Washington Post via Getty Images Two trends in Maine show the precarious future for the U.S., which seems woefully unequipped to handle a rapidly aging population. 1. 1/5 of residents are now 65+, with 15 states expected to follow by 2026, notes the WashPost's Jeff Stein. 2. Nursing homes are closing and struggling to find long-term care workers. That’s not helped by Medicare, Medicaid and private insurance — which have limited offerings for long-term care coverage. The big picture: America's 85 and older population will spike 200+% between 2015 and 2050, while the under 65 population will increase just 12%, per the Post. • That trend includes aging health care workers, who are disproportionately older in rural areas. Between the lines: “The U.S. is just starting this journey, and Maine is at the leading edge,” Maine Council on Aging's Jess Maurer told the Post. “As we are living longer, all the systems that have always worked for us may have to be changed.” • That includes the need for nearly 8 million more long-term care workers in the years to come, the Post cites.