Morphology and Function of the Road Network of Eastern Sonora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lunes 12 De Julio De 2021. CCVIII Número 4 Secc. I

• • • • • • DESARROLLO TERRITORIAL SliC~ETARÍA OE Oi:.SAJU tCLLO ~ C fl:A.fUO, TE~ JU TOQfA L V \IRB,A_NO AVISO DE DESLINDE SECRETARÍA DE DESARROLLO AGRARIO, TERRITORIAL Y URBANO Aviso de medición y deslinde del predio de presunta propiedad nacional denominado "LAS UVALAMAS" con una superficie aproximada de 83-27-38.940 hectáreas, ubicado en el Municipio de SUAQUI GRANDE, SONORA. La Dirección General de la Propiedad Rural, de la Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario, Territorial y Urbano, mediante Oficio núm. ll-210-DGPR-14607, de fecha 16 de diciembre de 2020, autorizó el deslinde y medición del predio presuntamente propiedad de la nación, arriba mencionado. Mediante el mismo oficio, se autorizó al suscrito lng. Mario Toledo Padilla, a llevar a cabo la medición y deslinde del citado predio, por lo que, en cumplimiento de los artículos 14 Constitucional, 3 de la Ley Federal de Procedimiento Administrativo, 160 de la Ley Agraria; 101, 104 y 105 Fracción I del Reglamento de la Ley Agraria en Materia de Ordenamiento de la Propiedad Rural, se publica, por una sola vez, en el Diario Oficial de la Federación, en el Periódico Oficial del Gobierno del Estado de Sonora, y en el periódico de mayor circulación de la entidad federativa de que se trate con efectos de notificación a los propietarios, poseedores, colindantes y todo aquel que considere que los trabajos de deslinde lo pudiesen afectar, a efecto de que dentro del plazo de 30 días hábiles contados a partir de la publicación del presente Aviso en el Diario Oficial de la Federación, comparezcan ante el suscrito para exponer lo que a su derecho convenga, así como para presentar la documentación que fundamente su dicho en copia certificada o en copia simple, acompañada del documento original para su cotejo, en términos de la fracción 11 del artículo 15-A de la Ley Federal de Procedimiento Administrativo. -

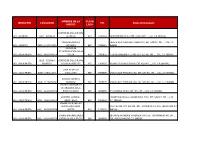

MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE LA UNIDAD CLAVE LADA TEL Domiciliocompleto

NOMBRE DE LA CLAVE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD TEL DomicilioCompleto UNIDAD LADA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 001 - ACONCHI 0001 - ACONCHI ACONCHI 623 2330060 INDEPENDENCIA NO. EXT. 20 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84920) CASA DE SALUD LA FRENTE A LA PLAZA DEL PUEBLO NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. 001 - ACONCHI 0003 - LA ESTANCIA ESTANCIA 623 2330401 (84929) UNIDAD DE DESINTOXICACION AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 3382875 7 ENTRE AVENIDA 4 Y 5 NO. EXT. 452 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) 0013 - COLONIA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 002 - AGUA PRIETA MORELOS COLONIA MORELOS 633 3369056 DOMICILIO CONOCIDO NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) CASA DE SALUD 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0009 - CABULLONA CABULLONA 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84305) CASA DE SALUD EL 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0046 - EL RUSBAYO RUSBAYO 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84306) CENTRO ANTIRRÁBICO VETERINARIO AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA SONORA 999 9999999 5 Y AVENIDA 17 NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) HOSPITAL GENERAL, CARRETERA VIEJA A CANANEA KM. 7 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA AGUA PRIETA 633 1222152 C.P. (84250) UNEME CAPA CENTRO NUEVA VIDA AGUA CALLE 42 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , AVENIDA 8 Y 9, COL. LOS OLIVOS C.P. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 1216265 (84200) UNEME-ENFERMEDADES 38 ENTRE AVENIDA 8 Y AVENIDA 9 NO. EXT. SIN NÚMERO NO. -

Some Geologic and Exploration Characteristics of Porphyry Copper Deposits in a Volcanic Environment, Sonora, Mexico

Some geologic and exploration characteristics of porphyry copper deposits in a volcanic environment, Sonora, Mexico Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic); maps Authors Solano Rico, Baltazar, 1946- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 03:12:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/566651 SOME GEOLOGIC AND EXPLORATION CHARACTERISTICS OF PORPHYRY COPPER DEPOSITS IN A VOLCANIC ENVIRONMENT, SONORA, MEXICO by Baltazar Solano Rico A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MINING AND GEOLOGICAL ENGINEERING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN GEOLOGICAL ENGINEERING In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 7 5 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. -

Colegio De Estudios Científicos Y Tecnológicos Del Estado De Sonora

Programa Institucional de Mediano Plazo 2011-2015 Colegio de Estudios Científicos y Tecnológicos del Estado de Sonora Programa Institucional de Mediano Plazo 2010-2015 Hermosillo, Sonora, Noviembre de 2010 1 Directorio CECyTES Sonora Lic. Guillermo Padrés Elías Gobernador del Estado de Sonora. H. Junta Directiva Mtro. Jorge Luis Ibarra Mendivil Secretario de Educación y Cultura, Presidente de la H. Junta Directiva. Lic. Clementina Elías Córdova Presidenta del Voluntariado del DIF Sonora, Representante del Gobierno del Estado de Sonora. Ing. Jesús Eduardo Chávez Leal Titular de Oficina de Servicios Federales de Apoyo a la Educación de Sonora, Representante del Gobierno Federal. Ing. Celso Gabriel Espinosa Corona Coordinador Nacional de Organismos Descentralizados Estatales de los CECyTE’s, Representante del Gobierno Federal. Lic. Luis Sierra Abascal Representante del Sector Social. Lic. Luis Carlos Durán Ríos Comisario Publico Ciudadano, Representante del Sector Social. Ing. Enrique Tapia Camou Representante del Sector Productivo. C.P. Luis Carlos Contreras Tapia Representante del Sector Productivo. Lic. Mario Alberto Corona Urquijo Titular del Órgano de Control y Desarrollo Administrativo en CECyTES Sonora. Mtro. Martín Alejandro López García Director General de CECyTES, Secretario Técnico de la H. Junta Directiva. M.C. José Carlos Aguirre Rosas Director Académico Ing. José Francisco Arriaga Moreno Director de Administración Profr. Gerardo Gaytán Fox Directora de de Vinculación Lic. Alfredo Ortega López Director de Planeación Lic. Jesús Carlos Castillo Rosas Secretario Particular Mtro. José Francisco Bracamonte Fuentes Secretario Técnico 2 Directores de Plantel Ing. Jazmín Guadalupe Navarro Garate CECyTES Bacame Lic. Juan José Araiza Rodríguez CECyTES Santa Ana Lic. Alma Flor Atondo Obregón CECyTES Ej. -

Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. Nogales, Santa Cruz Co., Ariz

r 4111111111111110 41111111111110 111111111111111b Ube Land of 1 Nayarit I ‘11•1114111111n1111111111n IMO In Account of the Great Mineral Region South of the Gila Mt) er and East from the Gulf of California to the Sierra Madre Written by ALLEN T. BIRD Editor The Oasis, Nogales, Arizona Published under the Auspices of the RIZONA AND SONORA CHAMBER. OF MINES 1904 THE OASIS PRINTING HOUSE, INCORPORATED 843221 NOGALES, ARIZONA Arizona and Sonora Chamber of Mines, Nogales, Arizona. de Officers. J. McCALLUM, - - President. A. SANDOVAL, First Vice-President. F. F. CRANZ, Second Vice-President. BRACEY CURTIS, - Treasurer. N. K. STALEY, - - Secretary. .ss Executive Committee. THEO. GEBLER. A. L PELLEGRIN. A. L. LEWIS. F. PELTIER. CON CY/017E. COLBY N. THOMAS. F. F. CRANZ. N the Historia del Nayarit, being a description of "The Apostolic Labors of the Society of Jesus in North America," embracing particularly that portion surrounding the Gulf of California, from the Gila River on the north, and comprising all the region westward from the main summits of the Sierra Madre, which history was first published in Barcelona in 1754, and was written some years earlier by a member of the order, Father Jose Ortega, being a compilation of writings of other friars—Padre Kino, Padre Fernanda Coasag, and others—there appear many interesting accounts of rich mineral regions in the provinces described, the mines of which were then in operation, and had been during more than a century preceding, constantly pour- ing a great volume of metallic wealth into that flood of precious metals which Mexico sent across the Atlantic to enrich the royal treasury of imperial Spain and filled to bursting the capacious coffers of the Papacy. -

Notes on the Winter Avifauna of Two Riparian Sites in Northern Sonora, Mexico

11 Notes on the Winter Avifauna of Two Riparian Sites in Northern Sonora, Mexico SCOTT 8. TERRILL Explorations just south of the border yield some intriguing comparisons to the winter birdlife of the southwestern U.S.: some continuums, some contrasts FOR MANY YEARS the region of the border between Mexico and the United States has been relatively well known in terms of bird species distribution. This is especially true in southeastern Arizona, southernmost Texas and southwestern California. In the first two cases, the ecological communities of these areas are unique in the United States. This offers the birder an opportunity to observe what are essentially tropical and sub-tropical species within U.S. boundaries. The border area in southwestern California (i.e., San Diego - Imperial Beach area) is heavily birded due to a relatively high probability of encountering "vagrant" transients, a somewhat diffe rent situation. Unfortunately, most of this border area coverage has been unilateral. The reasons for this are straightforward: bird listers are concerned with recording species within the standardized A.O. U. Check-list area; observers in general prefer to observe these birds and natural communities in the socially comfortable confines of their native country; birders headed south of the border are usually eager to reach more southerly latitudes where the species represent a greater difference from those of the U.S.; and fi nally, most interested persons would predict that the border areas of Mexico would support avifaunas quite similar to those just north of the border. During the winter of 1979- 1 980, Ken Rosenberg, Gary Rosenberg and I undertook some field work in northern Sonora. -

Spain's Arizona Patriots in Its 1779-1783 War

W SPAINS A RIZ ONA PA TRIOTS J • in its 1779-1783 WARwith ENGLAND During the AMERICAN Revolutuion ThirdStudy of t he SPANISH B ORDERLA NDS 6y Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough ~~~i~!~~¸~i ~i~,~'~,~'~~'~-~,:~- ~.'~, ~ ~~.i~ !~ :,~.x~: ~S..~I~. :~ ~-~;'~,-~. ~,,~ ~!.~,~~~-~'~'~ ~'~: . Illl ........ " ..... !'~ ~,~'] ." ' . ,~i' v- ,.:~, : ,r~,~ !,1.. i ~1' • ." ~' ' i;? ~ .~;",:I ..... :"" ii; '~.~;.',',~" ,.', i': • V,' ~ .',(;.,,,I ! © Copyright 1999 ,,'~ ;~: ~.~:! [t~::"~ "~, I i by i~',~"::,~I~,!t'.':'~t Granville W. and N.C. Hough 3438 Bahia blanca West, Aprt B Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 k ,/ Published by: SHHAR PRESS Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 http://mcmbers.aol.com/shhar SHHARPres~aol.com (714) $94-8161 ~I,'.~: Online newsletter: http://www.somosprimos.com ~" I -'[!, ::' I ~ """ ~';I,I~Y, .4 ~ "~, . "~ ! ;..~. '~/,,~e~:.~.=~ ........ =,, ;,~ ~c,z;YA':~-~A:~.-"':-'~'.-~,,-~ -~- ...... .:~ .:-,. ~. ,. .... ~ .................. PREFACE In 1996, the authors became aware that neither the NSDAR (National Society for the Daughters of the American Revolution) nor the NSSAR (National Society for the Sons of the American Revolution) would accept descendants of Spanish citizens of California who had donated funds to defray expenses ,-4 the 1779-1783 war with England. As the patriots being turned down as suitable ancestors were also soldiers,the obvious question became: "Why base your membership application on a money contribution when the ancestor soldier had put his life at stake?" This led to a study of how the Spanish Army and Navy had worked during the war to defeat the English and thereby support the fledgling English colonies in their War for Independence. After a year of study, the results were presented to the NSSAR; and that organization in March, 1998, began accepting descendants of Spanish soldiers who had served in California. -

Sonora, Mexico

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development SONORA, MEXICO, Sonora is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico and has made great strides in Sonora, building its human capital and skills. How can Sonora turn the potential of its universities and technological institutions into an active asset for economic and Mexico social development? How can it improve the equity, quality and relevance of education at all levels? Jaana Puukka, Susan Christopherson, This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional Patrick Dubarle, Jocelyne Gacel-Ávila, reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. Sonora, Mexico CONTENTS Chapter 1. Human capital development, labour market and skills Chapter 2. Research, development and innovation Chapter 3. Social, cultural and environmental development Chapter 4. Globalisation and internationalisation Chapter 5. Capacity building for regional development ISBN 978- 92-64-19333-8 89 2013 01 1E1 Higher Education in Regional and City Development: Sonora, Mexico 2013 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

Report on the Sonora Lithium Project

Report on the Sonora Lithium Project (Pursuant to National Instrument 43-101 of the Canadian Securities Administrators) Huasabas - Bacadehuachi Area (Map Sheet H1209) Sonora, Mexico o o centered at: 29 46’29”N, 109 6’14”W For 330 – 808 – 4th Avenue S. W. Calgary, Alberta Canada T2P 3E8 Tel. +1-403-237-6122 By Carl G. Verley, P. Geo. Martin F. Vidal, Lic. Geo. Geological Consultant Vice-President, Exploration Amerlin Exploration Services Ltd. Bacanora Minerals Ltd. 2150 – 1851 Savage Road Calle Uno # 312 Richmond, B.C. Canada V6V 1R1 Hermosillo, Mexico Tel. +1-604-821-1088 Tel. +52-662-210-0767 Ellen MacNeill, P.Geo. Geological Consultant RR5, Site25, C16 Prince Albert, SK Canada S6V 5R3 Tel. +1-306-922-6886 Dated: September 5, 2012. Bacanora Minerals Ltd. Report on the Sonora Lithium Project, Sonora, Mexico Date and Signature Page Date Dated Effective: September 5, 2012. Signatures Carl G. Verley, P.Geo. ____________________ Martin F. Vidal, Lic. Geo. Ellen MacNeill, P.Geo. Amerlin Exploration Services Ltd. - Consulting mineral exploration geologists ii Bacanora Minerals Ltd. Report on the Sonora Lithium Project, Sonora, Mexico Table of Contents 1.0 Summary ................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 3.0 Reliance on Other Experts ....................................................................................................... -

84920 Sonora 7226001 Aconchi Aconchi 84923 Sonora 7226001 Aconchi Agua Caliente 84923 Sonora 7226001 Aconchi Barranca Las Higuer

84920 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI ACONCHI 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI AGUA CALIENTE 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI BARRANCA LAS HIGUERITAS 84929 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI CHAVOVERACHI 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI EL RODEO (EL RODEO DE ACONCHI) 84925 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI EL TARAIS 84929 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI ESTABLO LOPEZ 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI HAVINANCHI 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA ALAMEDA 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA ALAMEDITA 84929 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA ESTANCIA 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA HIGUERA 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA LOMA 84929 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA MISION 84933 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA SAUCEDA 84924 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LAS ALBONDIGAS 84930 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LAS GARZAS 84924 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LOS ALISOS 84930 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI MAICOBABI 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI RAFAEL NORIEGA SOUFFLE 84925 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI REPRESO DE ROMO 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI SAN PABLO (SAN PABLO DE ACONCHI) 84934 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI TEPUA (EL CARRICITO) 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI TRES ALAMOS 84935 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI VALENCIA 84310 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA 18 DE AGOSTO (CORRAL DE PALOS) 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ABEL ACOSTA ANAYA 84270 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ACAPULCO 84313 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ADAN ZORILLA 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ADOLFO ORTIZ 84307 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA AGUA BLANCA 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ALBERGUE DIVINA PROVIDENCIA 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ALBERTO GRACIA GRIJALVA 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ALFONSO GARCIA ROMO 84303 SONORA -

PERFORACIÓN Y EQUIPAMIENTO DE POZOS GANADEROS EJERCICIO 2014 Municipio De Empleos Tipo Localidad De Apoyo Federal Cantidad Cantidad Estado Folio Solicitud Nombre(S) A

PADRÓN DE BENEFICIARIOS PROGRAMA DE FOMENTO GANADERO COMPONENTE: PERFORACIÓN Y EQUIPAMIENTO DE POZOS GANADEROS EJERCICIO 2014 Municipio de Empleos Tipo Localidad de Apoyo Federal Cantidad Cantidad Estado Folio Solicitud Nombre(s) A. paterno A. materno DDR CADER Aplicación de Caracteristicas Generados Solicitante Aplicación de Proyecto (Autorizado) Hombres Mujeres Proyecto Directos SONORA SR1400009896 FISICA JESUS ALBERTO DICOCHEA AGUILAR MAGDALENA NOGALES NOGALES HEROICA NOGALES PERFORACION DE POZO 8" $ 167,400.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009896 FISICA JESUS ALBERTO DICOCHEA AGUILAR MAGDALENA NOGALES NOGALES HEROICA NOGALES TUBERIA PVC CEDULA 40 $ 18,461.47 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009902 FISICA CARLOS ROBLES GRIJALVA URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN PILA ARMABLE $ 81,080.06 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009902 FISICA CARLOS ROBLES GRIJALVA URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN PERFORACION DE POZO $ 165,000.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009902 FISICA CARLOS ROBLES GRIJALVA URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN LINEA DE CONDUCCION DE AGUA $ 41,777.04 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009909 FISICA ENRIQUE ALONSO SALCIDO MONTAÑO URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN EQUIPO DE BOMBEO $ 34,641.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009909 FISICA ENRIQUE ALONSO SALCIDO MONTAÑO URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN PERFORACION DE POZO $ 119,700.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009914 FISICA FLORENCIO CRUZ BURROLA URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN PERFORACION DE POZO $ 123,000.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400010642 FISICA CESAR NAVARRO CRUZ URES BANAMICHI BAVIÁCORA BAVIÁCORA BOMBA SUMERGIBLE $ 7,200.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400010642 FISICA CESAR NAVARRO CRUZ URES BANAMICHI BAVIÁCORA BAVIÁCORA PERFORACION DE POZO $ -

MIN.160905 URES.Pdf

VERSION DE LA SESION ORDINARIA CELEBRADA POR LA HONORABLE LXI LEGISLATURA CONSTITUCIONAL DEL ESTADO LIBRE Y SOBERANO DE SONORA, EL DIA 05 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 2016. Presidencia del C. Dip. Jorge Luis Márquez Cázares (Asistencia de treinta y dos diputados) URES, SONORA Inicio: 11:23 Horas C. DIP. PRESIDENTE: Buenos días, antes de iniciar la sesión, me permito ceder el uso de la voz al contador público David Gracia Paz, presidente municipal de la Heroica Ures, Sonora, a efecto de que nos brinde unas palabras de bienvenida. C. C.P. DAVID GRACIA PAZ (PRESIDENTE MUNICIPAL DE URES, SONORA): Buenos días, muchas gracias diputado Jorge Luis Márquez Cázares, presidente de la mesa directiva, honorable Congreso del Estado libre y soberano de Sonora, 61 legislatura, sean ustedes muy bienvenidos a la heroica ciudad de Ures, el pueblo de los corazones, créanmelo que estamos muy contentos de recibirlos aquí en este lugar, me es muy grato saludar a compañeros presidentes municipales del Río, ex presidentes municipales de este municipio, medios de comunicación, a todos lo que se encuentran aquí esta mañana con nosotros les doy las más sinceras gracias por estar aquí compartiendo este lugar, comento con ustedes que la historia registra actos de hospitalidad y cariño de los habitantes de este valle para con sus visitantes, incluso 100 años antes de la fundación oficial de Ures, alrededor del año 1536, cuando después de haber caminado a pie 8 años de las costas de Florida, llega a Ures Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca con 3 sobrevivientes en una expedición de náufrago,