(GPS) Approach and the Origin of Ashkenazic Jews – a Reply to Flegontov Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J Ewish Community and Civic Commune In

Jewish community and civic commune in the high Middle Ages'' CHRISTOPH CLUSE 1. The following observations do not aim to provide a comprehensive phe nomenology of the J ewish community during the high and late medieval periods. Rather 1 wish to present the outlines of a model which describes the status of the Jewish community within the medieval town or city, and to ask how the concepts of >inclusion< and >exclusion< can serve to de scribe that status. Using a number of selected examples, almost exclusively drawn from the western regions of the medieval German empire, 1 will concentrate, first, on a comparison betweenJewish communities and other corporate bodies (>universitates<) during the high medieval period, and, secondly, on the means by which Jews and Jewish communities were included in the urban civic corporations of the later Middle Ages. To begin with, 1 should point out that the study of the medieval Jewish community and its various historical settings cannot draw on an overly rich tradition in German historical research. 1 The >general <historiography of towns and cities that originated in the nineteenth century accorded only sporadic attention to the J ews. Still, as early as 1866 the legal historian Otto Stobbe had paid attention to the relationship between the Jewish ::- The present article first appeared in a slightly longer German version entitled Die mittelalterliche jüdische Gemeinde als »Sondergemeinde« - eine Skizze. In: J OHANEK, Peter (ed. ): Sondergemeinden und Sonderbezirke in der Stadt der Vormoderne (Städteforschung, ser. A, vol. 52). Köln [et al.] 2005, pp. 29-51. Translations from the German research literature cited are my own. -

1 Genesis 10-‐11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, Shall We Open Our Bibles

Genesis 10-11 Study ID#12ID1337 Alright, shall we open our Bibles tonight to Genesis 10. If you're just joining us on Wednesday, you're only nine chapters behind. So you can catch up, all of those are online, they are in video, they are on audio. We are working on translating all of our studies online into Spanish. It'll take awhile, but it's being done. We are also transcribing every study so that you can have a written copy of all that's said. You won't have to worry about notes. It'll all be there, the Scriptures will be there. So that's also in the process. It'll take awhile, but that's the goal and the direction we're heading. So you can keep that in your prayers. Tonight we want to continue in our in-depth study of this book of beginnings, the book of Genesis, and we've seen a lot if you've been with us. We looked at the beginning of the earth, and the beginning of the universe, and the beginning of mankind, and the origin of marriage, and the beginning of the family, and the beginning of sacrifice and worship, and the beginning of the gospel message, way back there in Chapter 3, verse 15, when the LORD promised One who would come that would crush the head of the serpent, preached in advance. We've gone from creation to the fall, from the curse to its conseQuences. We watched Abel and then Cain in a very ungodly line that God doesn't track very far. -

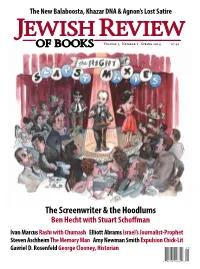

JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95

The New Balaboosta, Khazar DNA & Agnon’s Lost Satire JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95 The Screenwriter & the Hoodlums Ben Hecht with Stuart Schoffman Ivan Marcus Rashi with Chumash Elliott Abrams Israel’s Journalist-Prophet Steven Aschheim The Memory Man Amy Newman Smith Expulsion Chick-Lit Gavriel D. Rosenfeld George Clooney, Historian NEW AT THE Editor CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Associate Editor Amy Newman Smith Administrative Assistant Rebecca Weiss Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Publisher Eric Cohen Associate Publisher & Director of Marketing Lori Dorr NEW SPACE The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, The David Berg Rare Book Room is a state-of- Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication the-art exhibition space preserving and dis- of ideas and criticism published in Spring, Summer, playing the written word, illuminating Jewish Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 165 East 56th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022. history over time and place. For all subscriptions, please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or send $29.95 UPCOMING EXHIBITION ($39.95 outside of the U.S.) to Jewish Review of Books, Opening Sunday, March 16: By Dawn’s Early PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Please send notifi- cations of address changes to the same address or to Light: From Subjects to Citizens (presented by the [email protected]. -

Historical Sciences 85

Historical sciences 85 Short Report THE CALENDAR VOCABULARY AS A STUDY relations of the Samoyeds and Yenisseys it may be SOURCE OF ANCIENT CULTURAL- supposed the following peculiarities of the origin of LINGUISTIC CONTACTS OF SIBERIAN the names for conceptions “spring”, “winter” in the INDIGENOUS PEOPLES (TO THE PROBLEM Samoyed (Selkup) and the Yenissey (Ket) languages: OF THE ORIGIN OF THE WORDS “SPRING”, 1) The words “winter”, “spring” had been bor- “WINTER»IN THE SELKUP AND THE KET rowed by native speakers from each other during the LANGUAGES) period of the existence of Samoyed and Yenissey lin- Kolesnikova V. guistic communities. [email protected] 2) The words “winter”, “spring” had been bor- rowed by native speakers from each other after the Different ethnic groups had been living, mov- disintegration of indicated linguistic communities (or ing, assimilating on the territory of Western Siberia one of them). for a long time. Economic and cultural contacts be- 3) The words “winter”, “spring” have been tween representatives of these groups had been arising borrowed by native speakers not from each other, but during many years. The relations and the two-way from another source. influence of two peoples – the Samoyeds and Yenis- It is known that there are many words in seys (ancestors of modern Selkups and Kets) - is one Selkup and Ket borrowed from other, unrelated lan- example of such contacts. Samoyed-yenissey lexical guages. For example, words from Russian and Turkic equivalents demonstrated by some researchers may be have been fixed in the Selkup language. A whole given as the results of their relationship [1]. -

1 Research Article the Missing Link of Jewish European Ancestry: Contrasting the Rhineland and the Khazarian Hypotheses Eran

Research Article The Missing Link of Jewish European Ancestry: Contrasting the Rhineland and the Khazarian Hypotheses Eran Israeli-Elhaik1,2 1 Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA, 21208. 2 McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA, 21208. Running head: The Missing Link of Jewish European Ancestry Keywords: Jewish genome, Khazars, Rhineland, Ashkenazi Jews, population isolate, Population structure Please address all correspondence to Eran Elhaik at [email protected] Phone: 410-502-5740. Fax: 410-502-7544. 1 Abstract The question of Jewish ancestry has been the subject of controversy for over two centuries and has yet to be resolved. The “Rhineland Hypothesis” proposes that Eastern European Jews emerged from a small group of German Jews who migrated eastward and expanded rapidly. Alternatively, the “Khazarian Hypothesis” suggests that Eastern European descended from Judean tribes who joined the Khazars, an amalgam of Turkic clans that settled the Caucasus in the early centuries CE and converted to Judaism in the 8th century. The Judaized Empire was continuously reinforced with Mesopotamian and Greco-Roman Jews until the 13th century. Following the collapse of their empire, the Judeo-Khazars fled to Eastern Europe. The rise of European Jewry is therefore explained by the contribution of the Judeo-Khazars. Thus far, however, their contribution has been estimated only empirically; the absence of genome-wide data from Caucasus populations precluded testing the Khazarian Hypothesis. Recent sequencing of modern Caucasus populations prompted us to revisit the Khazarian Hypothesis and compare it with the Rhineland Hypothesis. -

1 the Genochip: a New Tool for Genetic Anthropology Eran Elhaik

The GenoChip: A New Tool for Genetic Anthropology Eran Elhaik1, Elliott Greenspan2, Sean Staats2, Thomas Krahn2, Chris Tyler-Smith3, Yali Xue3, Sergio Tofanelli4, Paolo Francalacci5, Francesco Cucca6, Luca Pagani3,7, Li Jin8, Hui Li8, Theodore G. Schurr9, Bennett Greenspan2, R. Spencer Wells10,* and the Genographic Consortium 1 Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 2 Family Tree DNA, Houston, TX 77008, USA 3 The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, UK 4 Department of Biology, University of Pisa, Italy 5 Department of Natural and Environmental Science, Evolutionary Genetics Lab, University of Sassari, Italy 6 National Research Council, Monserrato, Italy 7 Division of Biological Anthropology, University of Cambridge, UK 8 Fudan University, Shanghai, China 9 University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 10 National Geographic Society, Washington DC, USA *Please address all correspondence to Spencer Wells at [email protected] 1 Abstract The Genographic Project is an international effort using genetic data to chart human migratory history. The project is non-profit and non-medical, and through its Legacy Fund supports locally led efforts to preserve indigenous and traditional cultures. While the first phase of the project was focused primarily on uniparentally-inherited markers on the Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA, the next is focusing on markers from across the entire genome to obtain a more complete understanding of human genetic variation. In this regard, genomic admixture is one of the most crucial tools that will help us to analyze the genetic makeup and shared history of human populations. -

Kampf Um Wort Und Schrift

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Kampf um Wort Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Beiheft 90 und Schrift Russifizierung in Osteuropa Nach den Teilungen Polens und der Eroberung des Kaukasus im 19.–20. Jahrhundert und Zentralasiens im 18./19. Jahrhundert erhielt das Zarenreich Kontrolle über alte Kulturräume, die es im Zuge der Koloniali- sierung zu assimilieren versuchte. Diese Versuche erfolgten nicht Herausgegeben von Zaur Gasimov zuletzt mittels der Sprachpolitik. Russisch sollte im Bildungs- und Behördenwesen im gesamten Imperium Verbreitung finden, andere Sprachen sollten verdrängt werden. Diese Russifizierung lässt sich Schrift und Wort um Kampf von einer kurzen Phase der »Verwurzelung« unter Lenin bis weit ins 20. Jahrhundert nachverfolgen. Erst im Zuge der Perestrojka wurde die sowjetische Sprachpolitik öffentlich kritisiert: Die einzelnen Republiken konnten durch neue Sprachgesetze ein Aussterben der lokalen Sprachen verhindern. Der Herausgeber Dr. Zaur Gasimov ist Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte in Mainz. Zaur Gasimov (Hg.) (Hg.) Gasimov Zaur Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht www.v-r.de 9 783525 101223 V UUMS_Gasimov_VIEG_v2MS_Gasimov_VIEG_v2 1 005.03.125.03.12 115:095:09 Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Abteilung für Universalgeschichte Herausgegeben von Johannes Paulmann Beiheft 90 Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Kampf um Wort und Schrift Russifizierung in Osteuropa im 19.–20. Jahrhundert Herausgegeben von Zaur Gasimov Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN (Print) 978-3-525-10122-3 ISBN (OA) 978-3-666-10122-9 https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666101229 © 2012, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. -

Comparative Testing of DNA Segmentation Algorithms Using

Comparative Testing of DNA Segmentation Algorithms Using Benchmark Simulations Eran Elhaik,*,1 Dan Graur,1 and Kresˇimir Josic´2 1Department of Biology & Biochemistry, University of Houston 2Department of Mathematics, University of Houston *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Associate editor: Hideki Innan Abstract Numerous segmentation methods for the detection of compositionally homogeneous domains within genomic sequences have been proposed. Unfortunately, these methods yield inconsistent results. Here, we present a benchmark consisting of Research article two sets of simulated genomic sequences for testing the performances of segmentation algorithms. Sequences in the first set are composed of fixed-sized homogeneous domains, distinct in their between-domain guanine and cytosine (GC) content variability. The sequences in the second set are composed of a mosaic of many short domains and a few long ones, distinguished by sharp GC content boundaries between neighboring domains. We use these sets to test the performance of seven segmentation algorithms in the literature. Our results show that recursive segmentation algorithms based on the Jensen–Shannon divergence outperform all other algorithms. However, even these algorithms perform poorly in certain instances because of the arbitrary choice of a segmentation-stopping criterion. Key words: isochores, GC content, segmentation algorithms, Jensen–Shannon divergence statistic, entropy, genome composition, benchmark simulations. Introduction into compositionally homogeneous domains according to predefined criteria. Segmentation methods include non- In 1976, Bernardi and colleagues (Macaya et al. 1976) put overlapping, sliding window methods (Bernardi 2001; Clay forward a theory concerning the compositional makeup of et al. 2001; International Human Genome Sequencing Con- vertebrate genomes. This description, later christened ‘‘the ´ isochore theory’’ (Cuny et al. -

Jews in the Medieval German Kingdom

Jews in the Medieval German Kingdom Alfred Haverkamp translated by Christoph Cluse Universität Trier Arye Maimon-Institut für Geschichte der Juden Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur | Mainz Projekt “Corpus der Quellen zur Geschichte der Juden im spätmittelalterlichen Reich” Online Edition, Trier University Library, 2015 Synopsis I. Jews and Christians: Long-Term Interactions ......................................... 1 . Jewish Centers and Their Reach ......................................................... 1 . Jews Within the Christian Authority Structure ......................................... 5 . Regional Patterns – Mediterranean-Continental Dimensions .......................... 7 . Literacy and Source Transmission ........................................................ 9 II. The Ninth to Late-Eleventh Centuries .............................................. 11 . The Beginnings of Jewish Presence ..................................................... 11 . Qehillot: Social Structure and Legal Foundations ...................................... 15 . The Pogroms of ................................................................... 20 III. From the Twelfth Century until the Disasters of – ....................... 23 . Greatest Extension of Jewish Settlement ............................................... 23 . Jews and Urban Life ..................................................................... 26 . Jewish and Christian Communities ..................................................... 33 . Proximity to the Ruler and “Chamber -

On the Unfounded Enthusiasm for Soft Selective Sweeps III: the Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm That Isn’T

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article On the Unfounded Enthusiasm for Soft Selective Sweeps III: The Supervised Machine Learning Algorithm That Isn’t Eran Elhaik 1,* and Dan Graur 2 1 Department of Biology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 35, 22362 Lund, Sweden 2 Department of Biology & Biochemistry, University of Houston, Science & Research Building 2, Suite #342, 3455 Cullen Bldv., Houston, TX 77204-5001, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In the last 15 years or so, soft selective sweep mechanisms have been catapulted from a curiosity of little evolutionary importance to a ubiquitous mechanism claimed to explain most adaptive evolution and, in some cases, most evolution. This transformation was aided by a series of articles by Daniel Schrider and Andrew Kern. Within this series, a paper entitled “Soft sweeps are the dominant mode of adaptation in the human genome” (Schrider and Kern, Mol. Biol. Evolut. 2017, 34(8), 1863–1877) attracted a great deal of attention, in particular in conjunction with another paper (Kern and Hahn, Mol. Biol. Evolut. 2018, 35(6), 1366–1371), for purporting to discredit the Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution (Kimura 1968). Here, we address an alleged novelty in Schrider and Kern’s paper, i.e., the claim that their study involved an artificial intelligence technique called supervised machine learning (SML). SML is predicated upon the existence of a training dataset in which the correspondence between the input and output is known empirically to be true. Curiously, Schrider and Kern did not possess a training dataset of genomic segments known a priori to have evolved either neutrally or through soft or hard selective sweeps. -

Genesis (B'reshiyt 6:9 – 11:32) Introduction: Chapter 6

NOAH GENESIS (B’RESHIYT 6:9 – 11:32) INTRODUCTION: 1. Because of the wickedness – the mixing and mingling – God determined to blot out all inhabitants of the earth. a. Mankind had corrupted his way and, consequently, corrupted the earth itself. 2. Josephus records that Adam had predicted destruction of world by flood and fire. a. Antiquities of the Jews, Book I, chapter 2, paragraph iii. 3. Lamech named him “Noah” indicating that he would bring “rest,” meaning of name. a. Geneological record in Gen. 5 seems to indicate that he was born in 1056. b. Possibility that he was born in 1058, written in Hebrew as . 4. Noah was the remnant – “he found grace” in the eyes of the LORD; he was righteous, unpolluted and walked with God. a. Noah, like Adam, would be father of mankind after the flood. b. From the beginning, we see that there is always a remnant. c. Apparently, Noah was the ONLY one considered righteous. 5. The flood waters are called “the waters of Noah” in Isaiah 54:9. a. Rabbis deduce that the waters are Noah’s responsibility. b. He had been content to protect his own righteousness by distancing himself. 6. If he had completed responsibility to that generation fully, flood might not have happened. a. Inferring that, ultimately, God’s people are responsible for some events. b. “Sons of God” in Gen. 6 are how narrative begins; ends with corrupted earth. 7. Much is made of fact that Noah “walked with God” but Abraham “before Him.” a. Abraham is considered as spiritually superior to Noah. -

Mitochondrial Genome Diversity in the Central Siberian Plateau with Particular

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/656181; this version posted May 31, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Mitochondrial Genome Diversity in the Central Siberian Plateau with Particular Reference to Prehistory of Northernmost Eurasia S. V. Dryomov*,1, A. M. Nazhmidenova*,1, E. B. Starikovskaya*,1, S. A. Shalaurova1, N. Rohland2, S. Mallick2,3,4, R. Bernardos2, A. P. Derevianko5, D. Reich2,3,4, R. I. Sukernik1. 1 Laboratory of Human Molecular Genetics, Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, SBRAS, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation 2 Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA 3 Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA 4 Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA 5 Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, SBRAS, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation Corresponding author: Rem Sukernik ([email protected]) * These authors contributed equally to this work. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/656181; this version posted May 31, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract The Central Siberian Plateau was last geographic area in Eurasia to become habitable by modern humans after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM).