T Afraid of No Ghosts' Dark Tourism at Historic Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Read a PDF Version of This Media Release, Click Here

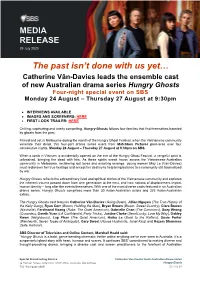

MEDIA RELEASE 29 July 2020 The past isn’t done with us yet… Catherine Văn-Davies leads the ensemble cast of new Australian drama series Hungry Ghosts Four-night special event on SBS Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm • INTERVIEWS AVAILABLE • IMAGES AND SCREENERS: HERE • FIRST LOOK TRAILER: HERE Chilling, captivating and utterly compelling, Hungry Ghosts follows four families that find themselves haunted by ghosts from the past. Filmed and set in Melbourne during the month of the Hungry Ghost Festival, when the Vietnamese community venerate their dead, this four-part drama series event from Matchbox Pictures premieres over four consecutive nights, Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm on SBS. When a tomb in Vietnam is accidentally opened on the eve of the Hungry Ghost Festival, a vengeful spirit is unleashed, bringing the dead with him. As these spirits wreak havoc across the Vietnamese-Australian community in Melbourne, reclaiming lost loves and exacting revenge, young woman May Le (Văn-Davies) must rediscover her true heritage and accept her destiny to help bring balance to a community still traumatised by war. Hungry Ghosts reflects the extraordinary lived and spiritual stories of the Vietnamese community and explores the inherent trauma passed down from one generation to the next, and how notions of displacement impact human identity – long after the events themselves. With one of the most diverse casts featured in an Australian drama series, Hungry Ghosts comprises more than 30 Asian-Australian actors and 325 -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

Dead Season1

158 Dead Season1 Caroline Sy HAU Professor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies Kyoto University In Kyoto, the Obon festival in honor of the spirits of ancestors falls around the middle of August. The day of the festival varies according to region and the type of calendar (solar or lunar) used. The Kanto region, including Tokyo, observes Obon in mid-July, while northern Kanto, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Okinawa celebrate their Old Bon (Kyu Bon) on the 15th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar. For most Japanese, though, August, shimmering Nilotic August, is dead season. Children have their school break, Parliament is not in session, and as many who can afford it go abroad. Because Kyoto sits in a valley, daytime temperature can run up to the mid- and even upper 30s. Obon is not a public holiday, but people often take leave to return to their ancestral hometowns to visit and clean the family burial grounds. The Bon Odori dance is based on the story of the monk Mokuren, who on Buddha’s advice was able to ease the suffering of his dead mother and who was said to have danced for joy at her release. The festival culminates in paper lanterns being floated across rivers and in dazzling displays of fireworks. An added attraction in Kyoto is the Daimonji festival held on August 16. Between 8:00 and 8:20 p.m., fires in the shape of the characters “great” (dai, ) and “wondrous dharma” (myo/ho ) and in the shapes of a boat and a torii gate are lit in succession on five mountains encircling the city. -

Tv Pg 08-09.Indd

8 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, August 9, 2011 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening August 9, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 ABC 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark Wipeout Take the Money and Combat Hospital Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Mentalist Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC It's Worth What? America's Got Talent Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD FOX Hell's Kitchen MasterChef Local 2 PBS KOOD 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land 23 ESPN 2 47 Food Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Billy Billy Billy Billy Billy Billy Billy Exterminator Local 4 ABC-KLBY AMC Rambo Part II Rambo Part II Flight of the Phoenix Local 5 KSCW WB 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM Wild Russia Wild Russia Wild Russia Wild Russia Russia Local 6 ABC-KLBY 6 Weather BET 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV Bringing Down Born to Dance The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show Weapons Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Flipping Out Flipping Out Flipping Out Flipping Out Housewives/NJ 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Extreme Makeover The Rookie 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 John King, USA Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Local 35 NFL 64 Oxygen 9 Eagle COMEDY Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Daily Colbert Tosh.0 Tosh.0 Local 9 NBC-KUSA 37 USA 65 We 29 CNBC 57 Disney DISC Local Local Auction Auction Auction Auction Auction Auction D. -

The Holzer Files,’ Returns with More Harrowing Tales from the Archives of America’S First Ghost Hunter

For Immediate Release: HIT TRAVEL CHANNEL SERIES, ‘THE HOLZER FILES,’ RETURNS WITH MORE HARROWING TALES FROM THE ARCHIVES OF AMERICA’S FIRST GHOST HUNTER Season Two Premieres on Thursday, October 29 at 11 p.m. ET/PT with a Special Halloween Week Launch Left to Right: Psychic medium Cindy Kaza, paranormal investigator Dave Schrader and equipment technician Shane Pittman NEW YORK (October 6, 2020) – After a groundbreaking freshman run, “The Holzer Files” returns with all-new investigations into Hans Holzer’s paranormal mysteries, launching with a special Halloween week premiere on Thursday, October 29 at 11 p.m. ET/PT. A dedicated paranormal team – led by paranormal investigator Dave Schrader, psychic medium Cindy Kaza and equipment technician Shane Pittman – revisits Hans Holzer’s most captivating cases. With the help of Holzer’s daughter, Alexandra Holzer, and researcher Gabe Roth, the team picks up where Holzer left off to re-examine the terrifying hauntings that he dedicated his life to researching. “The Holzer Files” is a cryptic mystery, bound by threads of truth, the voices of the past and the exploration of modern paranormal pioneers. Viewers will experience a chilling chase, fueled by Holzer’s rediscovered archival files and haunting cinematography. The second season, comprised of 13 brand new one-hour episodes, follows the team on the haunted trail of legendary cases – from an elegant mansion in New York City, home to one of the world’s most infamous hauntings to the historic Maryland tavern that hid John Wilkes Booth after he shot Abraham Lincoln. Recognized as the “father of the paranormal,” Hans Holzer’s legendary four-decade exploration into disturbing hauntings like the Amityville Horror house, helped spawn legions of supernatural enthusiasts, more than 120 books and even inspired Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis to write “Ghostbusters.” In each episode, the team culls through thousands of Holzer’s recently discovered documents, letters, photographs and chilling audio and visual recordings dating back to the 1950s. -

Historic House Museums

HISTORIC HOUSE MUSEUMS Alabama • Arlington Antebellum Home & Gardens (Birmingham; www.birminghamal.gov/arlington/index.htm) • Bellingrath Gardens and Home (Theodore; www.bellingrath.org) • Gaineswood (Gaineswood; www.preserveala.org/gaineswood.aspx?sm=g_i) • Oakleigh Historic Complex (Mobile; http://hmps.publishpath.com) • Sturdivant Hall (Selma; https://sturdivanthall.com) Alaska • House of Wickersham House (Fairbanks; http://dnr.alaska.gov/parks/units/wickrshm.htm) • Oscar Anderson House Museum (Anchorage; www.anchorage.net/museums-culture-heritage-centers/oscar-anderson-house-museum) Arizona • Douglas Family House Museum (Jerome; http://azstateparks.com/parks/jero/index.html) • Muheim Heritage House Museum (Bisbee; www.bisbeemuseum.org/bmmuheim.html) • Rosson House Museum (Phoenix; www.rossonhousemuseum.org/visit/the-rosson-house) • Sanguinetti House Museum (Yuma; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/museums/welcome-to-sanguinetti-house-museum-yuma/) • Sharlot Hall Museum (Prescott; www.sharlot.org) • Sosa-Carrillo-Fremont House Museum (Tucson; www.arizonahistoricalsociety.org/welcome-to-the-arizona-history-museum-tucson) • Taliesin West (Scottsdale; www.franklloydwright.org/about/taliesinwesttours.html) Arkansas • Allen House (Monticello; http://allenhousetours.com) • Clayton House (Fort Smith; www.claytonhouse.org) • Historic Arkansas Museum - Conway House, Hinderliter House, Noland House, and Woodruff House (Little Rock; www.historicarkansas.org) • McCollum-Chidester House (Camden; www.ouachitacountyhistoricalsociety.org) • Miss Laura’s -

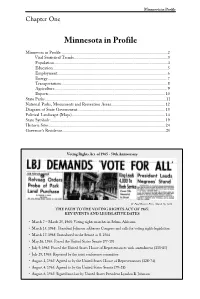

Minnesota in Profile

Minnesota in Profile Chapter One Minnesota in Profile Minnesota in Profile ....................................................................................................2 Vital Statistical Trends ........................................................................................3 Population ...........................................................................................................4 Education ............................................................................................................5 Employment ........................................................................................................6 Energy .................................................................................................................7 Transportation ....................................................................................................8 Agriculture ..........................................................................................................9 Exports ..............................................................................................................10 State Parks...................................................................................................................11 National Parks, Monuments and Recreation Areas ...................................................12 Diagram of State Government ...................................................................................13 Political Landscape (Maps) ........................................................................................14 -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

Ghost-Movies in Southeast Asia and Beyond. Narratives, Cultural

DORISEA-Workshop Ghost-Movies in Southeast Asia and beyond. Narratives, cultural contexts, audiences October 3-6, 2012 University of Goettingen, Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology Convenor: Peter J. Braeunlein Abstracts Post-war Thai Cinema and the Supernatural: Style and Reception Context Mary Ainslie (Kuala Lumpur) Film studies of the last decade can be characterised by escalating scholarly interest in the diverse film forms of Far East Asian nations. In particular, such focus often turns to the ways in which the horror film can provide a culturally specific picture of a nation that offers insight into the internal conflicts and traumas faced by its citizens. Considering such research, the proposed paper will explore the lower-class ‘16mm era’ film form of 1950s and 60s Thailand, a series of mass-produced live-dubbed films that drew heavily upon the supernatural animist belief systems that organised Thai rural village life and deployed a film style appropriate to this context. Through textual analysis combined with anthropological and historical research, this essay will explore the ways in which films such as Mae-Nak-Prakanong (1959 dir. Rangsir Tasanapayak), Nguu-Phii (1966 dir. Rat Saet-Thaa-Phak-Dee), Phii-Saht-Sen-Haa (1969 dir. Pan-Kam) and Nang-Prai-Taa-Nii (1967 dir. Nakarin) deploy such discourses in relation to a dramatic wider context of social upheaval and the changes enacted upon rural lower-class viewers during this era, much of which was specifically connected to the post-war influx of American culture into Thailand. Finally it will indicate that the influence of this lower-class film style is still evident in the contemporary New Thai industry, illustrating that even in this global era of multiplex blockbusters such audiences and their beliefs and practices are still prominent and remain relevant within Thai society. -

Hauntology Beyond the Cinema: the Technological Uncanny 66 Closings 78 5

Information manycinemas 03: dread, ghost, specter and possession ISSN 2192-9181 Impressum manycinemas editor(s): Michael Christopher, Helen Christopher contact: Matt. Kreuz Str. 10, 56626 Andernach [email protected] on web: www.manycinemas.org Copyright Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal. The authors are free to re - publish their text elsewhere, but they should mention manycinemas as the first me- dia which has published their article. According to §51 Nr. 2 UrhG, (BGH, Urt. v. 20.12.2007, Aktz.: I ZR 42/05 – TV Total) German law, the quotation of pictures in academic works are allowed if text and screenshot are in connectivity and remain unchanged. Open Access manycinemas provides open access to its content on the principle that mak - ing research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge. Front: Screenshot The cabinet of Caligari Contents Editorial 4 Helen Staufer and Michael Christopher Magical thrilling spooky moments in cinema. An Introduction 6 Brenda S. Gardenour Left Behind. Child Ghosts, The Dreaded Past, and Reconciliation in Rinne, Dek Hor, and El Orfanato 10 Cen Cheng No Dread for Disasters. Aftershock and the Plasticity of Chinese Life 26 Swantje Buddensiek When the Shit Starts Flying: Literary ghosts in Michael Raeburn's film Triomf 40 Carmela Garritano Blood Money, Big Men and Zombies: Understanding Africa’s Occult Narratives in the Context of Neoliberal Capitalism 50 Carrie Clanton Hauntology Beyond the Cinema: The Technological Uncanny 66 Closings 78 5 Editorial Sorry Sorry Sorry! We apologize for the late publishing of our third issue. -

Inheritance Path of Traditional Festival Culture from the Perspective of Ghost Festival in Luju Town

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 7, Ver. IV (July. 2014), PP 43-47 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Inheritance Path of Traditional Festival Culture from the Perspective of Ghost Festival in Luju Town Jiayi Lu, Jianghua Luo 1,2Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences at University, Center for Studies Education and Psychology of Ethnic Minorities in Southwestern China, Southwest University, Beibei , Chongqing 400715 Abstract: By participating in a series of activities of Ghost Festival on July 15th, teenagers naturally accept the ethical education of filial piety and benevolence. However, under the background of urbanization of villages, teenagers are away from their local families, and family controlling power and influence have been weakened. All these problems become prominent increasingly. As a result, the cultural connotations of Ghost Festival have been misinterpreted, and its survival and inheritance are facing a crisis. Therefore, we must grasp the essence in the inheritance of traditional cultures and make families and schools play their roles on the basis of combination of modern lives. Keywords: Ghost Festival, local villages, inheritance of culture, teenagers Fund Project: Comparative Study of the Status Quo of Educational Development of Cross-border Ethnic Groups in Southwestern China — major project of humanities and social science key research base which belongs to the Ministry of Education. (Project Number: 11JJD880028) About the Author: Lu Jiayi, student of Southwestern Ethnic Education and Psychology Research Center of Southwest University, Luo Jianghua, associate professor of Southwestern Ethnic Education and Psychology Research Center of Southwest University, PhD,Chongqing 400715. -

This Document Is Made Available Electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library As Part of an Ongoing Digital Archiving Project

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp MINNESOTA HISTORICAL Using the Power of History to Transform Lives 1~ SOCIETY PRESERVING > SHARING > CONNECTING January 15, 2021 Commissioner Jim Schowalter Minnesot a Management and Budget 400 Centennial Office Building 658 Cedar Street St. Paul, MN 55155 Senator Tom Bakk, Chair Representative Fue Lee, Cha ir Senate Capital Investment Committee House Capital lnvestment·committee Room 328 Capitol Room 485 State Office Building St. Paul, MN 55155 St. Paul, MN 55155 Represent ative M ike Nelson, Chair Senator Mary Kiffmeyer, Chair, Senate State House State Government Fin ance Committee Government Finance and Policy and Elections Committee Room 585 State Office Building Room 3103 Minnesota Senate Building St. Paul, MN 55 155 St. Paul, MN 55155 Dea r Commissioner, Senators, Representatives: Pursuant to M innesota Statutes, Chapter 16B.307, subdivision 2, the M innesota Historical Society is submitting 1) "a list of the [Asset Preservation] projects t hat have been funded with money under this program during the preceding calendar year" and 2) "a list of those priority asset preservation projects for which state bond proceeds fund appropriations w ill be sought during t hat year's legislative session." Expenditures made during ca lendar yea r 2020 on Asset Preservation Projects are as follows: Asset Preservation Projects (2017 Appropriation) Split Rock - HVAC 66,735