Break and Enter and Architecture: "Places" Without Foundations Donna Morgan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imagereal Capture

Some Aspects of Theft of Computer Software by M. Dunning I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to test the capability of New Zealand law to adequately deal with the impact that computers have on current notions of crimes relating to property. Has the criminal law kept pace with technology and continued to protect property interests or is our law flexible enough to be applied to new situations anyway? The increase of the moneyless society may mean a decrease in money motivated crimes of violence such as robbery, and an increase in white collar crime. Every aspect of life is being computerised-even our per sonality is on character files, with the attendant )ossibility of criminal breach of privacy. The problems confronted in this area are mostly definitional. While it may be easy to recognise morally opprobrious conduct, the object of such conduct may not be so easily categorised as criminal. A factor of this is a general lack of understanding of the computer process, so this would seem an appropriate place to begin the inquiry. II. THE COMPUTER Whiteside I identifies five key elements in a computer system. (1) Translation of data into a form readable by the computer, called input; and subject to manipulation by the introduction of false data. Remote terminals can be situated anywhere outside the cen tral processing unit (CPU), connected by (usually) telephone wires over which data may be transmitted, e.g. New Zealand banks on line to Databank. Outside users are given a site code number (identifying them) and an access code number (enabling entry to the CPU) which "plug" their remote terminal in. -

Common Law Fraud Liability to Account for It to the Owner

FRAUD FACTS Issue 17 March 2014 (3rd edition) INFORMATION FOR ORGANISATIONS Fraud in Scotland Fraud does not respect boundaries. Fraudsters use the same tactics and deceptions, and cause the same harm throughout the UK. However, the way in which the crimes are defined, investigated and prosecuted can depend on whether the fraud took place in Scotland or England and Wales. Therefore it is important for Scottish and UK-wide businesses to understand the differences that exist. What is a ‘Scottish fraud’? Embezzlement Overview of enforcement Embezzlement is the felonious appropriation This factsheet focuses on criminal fraud. There are many interested parties involved in of property without the consent of the owner In Scotland criminal fraud is mainly dealt the detection, investigation and prosecution with under the common law and a number where the appropriation is by a person who of statutory offences. The main fraud offences has received a limited ownership of the of fraud in Scotland, including: in Scotland are: property, subject to restoration at a future • Police Service of Scotland time, or possession of property subject to • common law fraud liability to account for it to the owner. • Financial Conduct Authority • uttering There is an element of breach of trust in • Trading Standards • embezzlement embezzlement making it more serious than • Department for Work and Pensions • statutory frauds. simple theft. In most cases embezzlement involves the appropriation of money. • Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. It is important to note that the Fraud Act 2006 does not apply in Scotland (apart from Statutory frauds s10(1) which increases the maximum In addition there are a wide range of statutory Investigating fraud custodial sentence for fraudulent trading to offences which are closely related to the 10 years). -

Criminal Law: Conspiracy to Defraud

CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD LAW COMMISSION LAW COM No 228 The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 228) CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD Item 5 of the Fourth Programme of Law Reform: Criminal Law Laid before Parliament bj the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to sc :tion 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 December 1994 LONDON: 11 HMSO E10.85 net The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Brooke, Chairman Professor Andrew Burrows Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 A. Background to the report 1. Our work on conspiracy generally 1.2 1 2. Restrictions on charging conspiracy to defraud following the Criminal Law Act 1977 1.8 3 3. The Roskill Report 1.10 4 4. The statutory reversal of Ayres 1.11 4 5. Law Commission Working Paper No 104 1.12 5 6. Developments in the law after publication of Working Paper No 104 1.13 6 7. Our subsequent work on the project 1.14 6 B. A general review of dishonesty offences 1.16 7 C. Summary of our conclusions 1.20 9 D. -

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, 'The Failure of Criminal Law To

Dr Stephen Copp and Alison Cronin, ‘The Failure of Criminal Law to Control the Use of Off Balance Sheet Finance During the Banking Crisis’ (2015) 36 The Company Lawyer, Issue 4, 99, reproduced with permission of Thomson Reuters (Professional) UK Ltd. This extract is taken from the author’s original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: http://login.westlaw.co.uk/maf/wluk/app/document?&srguid=i0ad8289e0000014eca3cbb3f02 6cd4c4&docguid=I83C7BE20C70F11E48380F725F1B325FB&hitguid=I83C7BE20C70F11 E48380F725F1B325FB&rank=1&spos=1&epos=1&td=25&crumb- action=append&context=6&resolvein=true THE FAILURE OF CRIMINAL LAW TO CONTROL THE USE OF OFF BALANCE SHEET FINANCE DURING THE BANKING CRISIS Dr Stephen Copp & Alison Cronin1 30th May 2014 Introduction A fundamental flaw at the heart of the corporate structure is the scope for fraud based on the provision of misinformation to investors, actual or potential. The scope for fraud arises because the separation of ownership and control in the company facilitates asymmetric information2 in two key circumstances: when a company seeks to raise capital from outside investors and when a company provides information to its owners for stewardship purposes.3 Corporate misinformation, such as the use of off balance sheet finance (OBSF), can distort the allocation of investment funding so that money gets attracted into less well performing enterprises (which may be highly geared and more risky, enhancing the risk of multiple failures). Insofar as it creates a market for lemons it risks damaging confidence in the stock markets themselves since the essence of a market for lemons is that bad drives out good from the market, since sellers of the good have less incentive to sell than sellers of the bad.4 The neo-classical model of perfect competition assumes that there will be perfect information. -

Future Identities: Changing Identities in the UK – the Next 10 Years DR 19: Identity Related Crime in the UK David S

Future Identities: Changing identities in the UK – the next 10 years DR 19: Identity Related Crime in the UK David S. Wall Durham University January 2013 This review has been commissioned as part of the UK Government’s Foresight project, Future Identities: Changing identities in the UK – the next 10 years. The views expressed do not represent policy of any government or organisation DR19 Identity Related Crime in the UK Contents Identity Related Crime in the UK ............................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Identity Theft (theft of personal information) .................................................................................... 6 3. Creating a false identity ...................................................................................................................... 9 4. Committing Identity Fraud ................................................................................................................ 12 5. New forms of identity crime ............................................................................................................. 14 6. The law and identity crime................................................................................................................ 16 7. Conclusions ...................................................................................................................................... -

A Timely History of Cheating and Fraud Following Ivey V Genting Casinos (UK)

The honest cheat: a timely history of cheating and fraud following Ivey v Genting Casinos (UK) Ltd t/a Crockfords [2017] UKSC 67 Cerian Griffiths Lecturer in Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, Lancaster University Law School1 Author email: [email protected] Abstract: The UK Supreme Court took the opportunity in Ivey v Genting Casinos (UK) Ltd t/a Crockfords [2017] UKSC 67 to reverse the long-standing, but unpopular, test for dishonesty in R v Ghosh. It reduced the relevance of subjectivity in the test of dishonesty, and brought the civil and the criminal law approaches to dishonesty into line by adopting the test as laid down in Royal Brunei Airlines Sdn Bhd v Tan. This article employs extensive legal historical research to demonstrate that the Supreme Court in Ivey was too quick to dismiss the significance of the historical roots of dishonesty. Through an innovative and comprehensive historical framework of fraud, this article demonstrates that dishonesty has long been a central pillar of the actus reus of deceptive offences. The recognition of such significance permits us to situate the role of dishonesty in contemporary criminal property offences. This historical analysis further demonstrates that the Justices erroneously overlooked centuries of jurisprudence in their haste to unite civil and criminal law tests for dishonesty. 1 I would like to thank Lindsay Farmer, Dave Campbell, and Dave Ellis for giving very helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this article. I would also like to thank Angus MacCulloch, Phil Lawton, and the Lancaster Law School Peer Review College for their guidance in developing this paper. -

Conspiracy and Attempts Consultation

The Law Commission Consultation Paper No 183 CONSPIRACY AND ATTEMPTS A Consultation Paper The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Etherton, Chairman Mr Stuart Bridge Mr David Hertzell Professor Jeremy Horder Kenneth Parker QC Professor Martin Partington CBE is Special Consultant to the Law Commission responsible for housing law reform. The Chief Executive of the Law Commission is Steve Humphreys and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WC1N 2BQ. This consultation paper, completed on 17 September 2007, is circulated for comment and criticism only. It does not represent the final views of the Law Commission. The Law Commission would be grateful for comments on its proposals before 31 January 2008. Comments may be sent either – By post to: David Hughes Law Commission Conquest House 37-38 John Street Theobalds Road London WC1N 2BQ Tel: 020-7453-1212 Fax: 020-7453-1297 By email to: [email protected] It would be helpful if, where possible, comments sent by post could also be sent on disk, or by email to the above address, in any commonly used format. We will treat all responses as public documents in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act and we will include a list of all respondents' names in any final report we publish. Those who wish to submit a confidential response should contact the Commission before sending the response. We will disregard automatic confidentiality disclaimers generated by an IT system. -

Part Xi – Laws of Attempted Crime

Criminal Law and Procedure 11 – Attempted Crime PART XI – LAWS OF ATTEMPTED CRIME I Introduction A Inchoate Crimes Inchoate crimes encompass doctrines of attempt, incitement and conspiracy, which share the common characteristic of making it criminal to participate in the commission of incomplete offences. Here, we are specifically concerned with attempt. Laws of attempt extend criminal liability beyond acts of a defendant to include what they try but fail to do. The general common law doctrine of attempt states that an attempt to commit a crime is itself a crime. However, most states and territories have introduced legislation codifying the doctrine into statutory form (see, in Victoria, Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) ss 321M-S). The difficulty arises in attempting to articulate the legal boundaries to this doctrine. For example, if I try to kill a person but am unable to achieve that result (eg, because of police intervention or my own incompetence or mistake), how close to committing the full crime must I be in order to be found guilty of attempted murder? B Relationship between Inchoate Crimes and Other Offences Laws of attempt may be distinguished from specific crimes that set a penalty for some lesser offence (eg, attempted murder in New South Wales and South Australia – but not Victoria, in which attempted murder is covered by the general law of attempt). Attempted crimes are also different from crimes whose actus reus consists of a lesser (often summary) offence with an intention to commit a further crime (see, eg, Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) ss 31, 40). The commission of these offences is a complete, and not inchoate, crime. -

Mens Rea Principle and Criminal Jurisprudence in Nigeria*

MENS REA PRINCIPLE AND CRIMINAL JURISPRUDENCE IN NIGERIA* Abstract This paper discusses the possibility or otherwise of the application of the common law doctrine of mens rea in Nigerian criminal jurisprudence. Our study discovers that the relevant provisions of the Criminal Code are exhaustive for considering and deciphering the criminal intent, if any, of an accused in view of conviction and sentencing. This paper agrees totally with the principle that once local statutes contain sufficient provisions for a consideration of any relevant legal issue within a particular jurisdiction, it would no longer be apropos to undertake a voyage or have recourse to any legal system outside the jurisdiction. At best, one can only be persuaded by such extra-jurisdictional concerns. This paper finally makes some recommendations towards the improvement of the justice system in the relevant matters. Critical and hermeneutical approaches constitute our methodology. Introduction The doctrine of mens rea is a central distinguishing feature of criminal justice system in old common law traditions. Yet it is one very controversial principle which suffers from an untold degree of confusion in its meaning. This problem of fluidity in denotation becomes all the more manifest when the courts are faced with the task of determining the guilt or criminal liability of a suspect. Under English criminal law, this hermeneutical problem had been a result of sundry causes. First and foremost, there are two distinct though interconnected levels of meaning attributable to the expression mens rea, namely, the narrow and the broad. While the former signifies the specific mental element that is required to be defined and proved in respect of a particular offence, the latter refers to a general principle of criminal responsibility which demands proof of a guilty mind against the accused. -

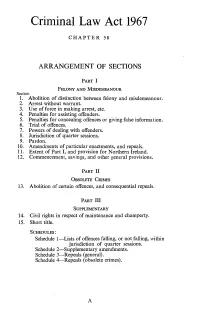

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

Theft Act 1968

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Theft Act 1968. (See end of Document for details) Theft Act 1968 1968 CHAPTER 60 General and consequential provisions 2 Theft Act 1968 (c. 60) SCHEDULE 2 – Miscellaneous and Consequential Amendments Document Generated: 2021-04-11 Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Theft Act 1968. (See end of Document for details) SCHEDULES X1SCHEDULE 2 Section 33(1),(2). MISCELLANEOUS AND CONSEQUENTIAL AMENDMENTS Editorial Information X1 The text of Schedule 2 is in the form in which it was originally enacted: it was not reproduced in Statutes in Force and, except as specified, does not reflect any amendments or repeals which may have been made prior to 1.2.1991. F1 PART I Textual Amendments F1 Sch. 2 Pt. I repealed (26.3.2001) by S.I. 2001/1149, art. 3(2), Sch. 2 (with art. 4(11)) . 1 The Post Office Act 1953 shall have effect subject to the amendments provided for by this Part of this Schedule (and, except in so far as the contrary intention appears, those amendments have effect throughout the British postal area). 2 Sections 22 and 23 shall be amended by substituting for the word “felony” in section 22(1) and section 23(2) the words “a misdemeanour”. and by omitting the words “of this Act and” in section 23(1). 3 In section 52, as it applies outside England and Wales, for the words from “be guilty” onwards there shall be substituted the words “be guilty of a misdemeanour and be liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years”. -

Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality? Chen Yehudai

Marquette Law Review Volume 92 Article 6 Issue 4 Summer 2009 Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality? Chen Yehudai Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Chen Yehudai, Informational Blackmail: Survived by Technicality?, 92 Marq. L. Rev. 779 (2009). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol92/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATIONAL BLACKMAIL: SURVIVED BY TECHNICALITY? CHEN YEHUDAI Blackmail constitutes one of the most intriguing puzzles in criminal law: How can two legal rights—i.e., a threat to disclose true but reputation-damaging information and, independently, a simple demand for money—make a legal wrong? The puzzle gets even more complicated when we take into account that it is not unlawful for one who holds embarrassing information to accept an offer of payment made by an unthreatened recipient in return for a promise not to disclose the information. In order to answer this question, this Article surveys and analyzes the development of the law of informational blackmail and criminal libel in English and American law and argues that the modern crime of blackmail is the result of an “historical accident” stemming from the historical classification of blackmail as a property offense instead of a reputation-protecting offense. The Article argues that when enacted, the prohibition on informational blackmail was meant to protect the interest of reputation as a supplement to the law of criminal libel.