MH-1997-October-Geissler.Pdf (6.817Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

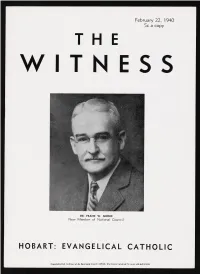

The W I T N E

February 22, 1940 5c a copy THE WITNESS DR. FRANK W. MOORE New Member of National Council HOBART: EVANGELICAL CATHOLIC Copyright 2020. Archives of the Episcopal Church / DFMS. Permission required for reuse and publication. SCHOOLS CLERGY NOTES SCHOOLS BARROWS, W. S., retired headmaster of De- Veaux School, Niagara Falls, N. Y., died at tElfg dînerai ©ijcologtcal the age of 79 on Jan. 27th in Lexington, Va. K e m p e r 1T O X ^em in arg BARTH, T. N., rector of St. Bartholomew’s p Church, Baltimore, Md., has accepted a call KENOSHA, WISCONSIN Three-year undergraduate to Calvary Church, Memphis, Tenn., and course of prescribed and elective will take over the duties in March. Episcopal Boarding and Day School. DUNSTAN, A. M., rector of St. Thomas Preparatory to all colleges. Unusual study. Church, Dover, N. H., since 1927, resigned his position on February 1st. opportunities in Art and Music. Fourth-year course for gradu FORTUNE, Ft V. D., formerly assistant Complete sports program. Junior ates, offering larger opportunity minister at St. Paul’s Church, Cleveland School. Accredited. Address: for specialization. Heights, Ohio, was instituted as rector of St. Paul’s Church, Steubenville, Ohio, on SISTERS OF ST. MARY Provision for more advanced January 25th by Bishop Beverley D. Tucker. work, leading to degrees of S.T.M. HATHEWAY, C. H., former canon of the Box W. T. and B.Th. Cathedral of All Saints, Albany, New York, Kemper Hall Kenosha, Wisconsin died at his home in Hudson on February ADDRESS 12th. He was 80 years of age. -

John Vardill: a Loyalist's Progress

JOHN VARDILL: A LOYALIST'S PROGRESS by STEVEN GRAHAM WIGELY .A., University of California at Irvine, 1971 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1975 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of History The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of a loyalist of the American Revolution named John .Vardill. A native of New York who went to England in 1774, he was an Anglican clergyman, a pamphlet• eer, a professor at King's College (New York), and a spy for the British. The purpose of the thesis is: 1. to tell his story, and 2. to argue that his loyalism was a perfectly rea• sonable consequence of his environment and experiences. The text begins with an Introduction (Chapter I) which places Vardill in colonial and English society, and justifies studying one who was neither among the very powerful nor the very weak. It then proceeds to a consideration of the circum• stances and substance of his claim for compensation from the , British government after the war (Chapter II). -

Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2009 Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776 Stephen M. Volpe College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Volpe, Stephen M., "Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626590. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4yj8-rx68 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Toleration and Reform: Virginia’s Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776 Stephen M. Volpe Pensacola, Florida Bachelor of Arts, University of West Florida, 2004 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2009 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts t / r ^ a — Stephen M. Volpe Approved by the Committee, July, 2009 Committee Chair Dr. Christopher Grasso, Associate Professor of History Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary ___________H h r f M ________________________ Dr. Jam es Axtell, Professor Emeritus of History Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary X ^ —_________ Dr. -

The Living Church· Iune 4

THE PARISH ADMINISTRATION/TRIENNIAL ISSUE [IVING CHURCH AN INDEPENDENT WEEKLY SERVING EPISCOPALIANS• JUNE 4, 2006 • $2.50 300 Years of Chang·ng Fortunes WHY DO "IN-THE-KNOW " EPISCOPALIANS CHOOSE WESTMINSTER COMMUNITIE S OF FLORIDA? They know about the unequalled Convenience Location Amenities Dining choices Housekeeping service Property and appliance maintenance Security Estate planning options Continuum of care Active lifestyle C oME AND STAY TH REE DAYS AND TWO ATTENTION Episcopal priests, missionaries, Christian NI GHTS ON US ! * educators, their spouses or surviving spouses. You may be eligible for a 10 10 entnnce f P n at our Bradenton, Experience urban excitement, St. Petersburg, and Jacksonville communities through our waterfront elegance , or Honorable Service Grant Program. Call coordinator, wooded serenity at a Donna Smaage, today at (800) 948-1881. Westminster community and let us impress you with our Westminster Communities of Florida signature Legendary Service' M. www.WestminsterRetirement.com • TransportJtlon ,snot included. (800) 948- 1881 ' Bradenton I Ft. Lauderdale I Ft. Walton Beach IJacksonville Orlando I Pensacola I Sr. Petersburg I Tallahassee I Winter Park Comefor the Lifestyle.Stay for a Lifetimer" The objective of THELIVING CHURCHmagazine is to build up the body of Christ, by describing how God is moving in his Church; by reporting news of the Church in an unbiased manner; and by presenting diverse points of view. THIS WEEK ---------- NEWS 21 Sensitive Issues to be Addressed Early at General Convention FEATURES 15 Faith in Daily Life Anne Rowthom BYPETER EATON 18 ECW Offers Change of Pace During General Convention Beth Marqurut (center left) and others 26 with Spokes for F'olks. -

The Episcopate in America

4* 4* 4* 4 4> m amenta : : ^ s 4* 4* 4* 4 4* ^ 4* 4* 4* 4 THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES GIFT OF Commodore Byron McCandless THe. UBKARY OF THE BISHOP OF SPRINGFIELD WyTTTTTTTTTTTT*'fW CW9 M IW W W> W W W W9 M W W W in America : : fTOfffiWW>fffiWiW * T -r T T Biographical and iiogtapl)icai, of tlje Bishops of tije American Ciwrct), toitl) a l&reliminarp Cssap on tyt Historic episcopate anD 2Documentarp Annals of tlje introduction of tl)e Anglican line of succession into America William of and Otstortogmpljrr of tljr American * IW> CW tffi> W ffi> ^W ffi ^ ^ CDttfon W9 WS W fW W <W $> W IW W> W> W> W c^rtjStfan Hitetatute Co, Copyright, 1895, BY THE CHRISTIAN LITERATURE COMPANY. CONTENTS. PAGE ADVERTISEMENT vii PREFACE ix INTRODUCTION xi BIOGRAPHIES: Samuel Seabury I William White 5 Samuel Provoost 9 James Madison 1 1 Thomas John Claggett 13 Robert Smith 15 Edward Bass 17 Abraham Jarvis 19 Benjamin Moore 21 Samuel Parker 23 John Henry Hobart 25 Alexander Viets Griswold 29 Theodore Dehon 31 Richard Channing Moore 33 James Kemp 35 John Croes 37 Nathaniel Bowen 39 Philander Chase 41 Thomas Church Brownell 45 John Stark Ravenscroft 47 Henry Ustick Onderdonk 49 William Meade 51 William Murray Stone 53 Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk 55 Levi Silliman Ives 57 John Henry Hopkins 59 Benjamin Bosworth Smith 63 Charles Pettit Mcllvaine 65 George Washington Doane 67 James Hervey Otey 69 Jackson Kemper 71 Samuel Allen McCoskry .' 73 Leonidas Polk 75 William Heathcote De Lancey 77 Christopher Edwards Gadsden 79 iii 956336 CONTENTS. -

Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints Is the Fruit of the Committee’S Careful and Painstaking Work

Holy Women, Holy Men Celebrating the Saints Conforming to General Convention 2009 Copyright © 2010 i The Church Pension Fund. For review and trial use only. Copyright © 2010 by The Church Pension Fund Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large scale reproduction, or reproduction for sale, of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated is prohibited. ISBN 978-0-89869-637-0 ISBN 978-0-89869-662-2 (Kindle) ISBN 978-0-89869-678-3 (E-book) 5 4 3 2 1 Church Publishing Incorporated 445 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10016 ii Copyright © 2010 The Church Pension Fund. For review and trial use only. Blessed feasts of blessed martyrs, holy women, holy men, with affection’s recollections greet we your return again. Worthy deeds they wrought, and wonders, worthy of the Name they bore; we, with meetest praise and sweetest, honor them for evermore. Twelfth century Latin text, translated John Mason Neale #238, The Hymnal 1982 Copyright © 2010 iii The Church Pension Fund. For review and trial use only. This resource has been many years in development, and it represents a major addition to the calendar of saints for the Episcopal Church. We can be grateful for the breadth of holy experience and wisdom which shine through these pages. May that light enlighten your life and the lives of those with whom you worship! —The Most Rev. Katharine Jefferts Schori, Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church iv Copyright © 2010 The Church Pension Fund. -

A War of Religion

A War of Religion Dissenters, Anglicans, and the American Revolution James B. Bell PPL-UK_WR-Bell_FM.qxd 3/27/2008 1:52 PM Page i Studies in Modern History General Editor: J. C. D. Clark, Joyce and Elizabeth Hall Distinguished Professor of British History, University of Kansas Titles include: James B. Bell Mark Keay A WAR OF RELIGION WILLIAM WORDSWORTH’S Dissenters, Anglicans, and the GOLDEN AGE THEORIES DURING American Revolution THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION IN ENGLAND, 1750–1850 James B. Bell THE IMPERIAL ORIGINS OF THE Kim Lawes KING’S CHURCH IN EARLY AMERICA, PATERNALISM AND POLITICS 1607–1783 The Revival of Paternalism in Early Nineteenth-Century Britain Jonathan Clark and Howard Erskine-Hill (editors) Marisa Linton SAMUEL JOHNSON IN HISTORICAL THE POLITICS OF VIRTUE IN CONTEXT ENLIGHTENMENT FRANCE Eveline Cruickshanks and Howard Karin J. MacHardy Erskine-Hill WAR, RELIGION AND COURT THE ATTERBURY PLOT PATRONAGE IN HABSBURG Diana Donald and AUSTRIA Frank O’Gorman (editors) The Social and Cultural ORDERING THE WORLD IN THE Dimensions of Political Interaction, EIGHTEENTH CENTURY 1521–1622 Richard D. Floyd James Mackintosh RELIGIOUS DISSENT AND POLITICAL VINDICIÆ GALLICÆ MODERNIZATION Defence of the French Revolution: Church, Chapel and Party in A Critical Edition Nineteenth-Century England Robert J. Mayhew Richard R. Follett LANDSCAPE, LITERATURE AND EVANGELICALISM, PENAL THEORY ENGLISH RELIGIOUS CULTURE, AND THE POLITICS OF CRIMINAL 1660–1800 LAW REFORM IN ENGLAND, Samuel Johnson and Languages of 1808–30 Natural Description Andrew Godley Marjorie Morgan JEWISH IMMIGRANT NATIONAL IDENTITIES AND TRAVEL ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN NEW YORK IN VICTORIAN BRITAIN AND LONDON, 1880–1914 James Muldoon William Anthony Hay EMPIRE AND ORDER THE WHIG REVIVAL, 1808–1830 The Concept of Empire, 800–1800 PPL-UK_WR-Bell_FM.qxd 3/27/2008 1:52 PM Page ii W. -

REPORT to the 76TH GENERAL CONVENTION 185 Standing Commission on Liturgy and Music

Standing Commission on Liturgy and Music STANDING COMMISSION ON LITURGY AND MUSIC MEMBERSHIP Ms. Julia Huttar Bailey, Chair Michigan, 2009 The Rt. Rev. George Wayne Smith, Vice-chair Missouri, 2009 The Rev. Devon Anderson, Special Rep. PHOD,+ Minnesota, 2009 The Rt. Rev. Sergio Carranza-Gomez, Resigned Los Angeles, 2012 Mr. Samuel Cheung New York, 2012 The Rev. Canon Gregory M. Howe, Delaware Custodian of the Standard Book Dr. Carl MaultsBy Washington, 2009 The Very Rev. Ernesto R. Medina Nebraska, 2009 The Rev. Dr. Ruth Meyers** Chicago, 2009 Ms. Sandra Montes Texas, 2012 The Rev. Dr. Clayton L. Morris DFMS; Liturgical Officer+ California Ms. Jeannine Otis New York, 2012 The Rev. Jennifer Phillips Rhode Island, 2012 Mrs. Mildred Springer Nevada, 2009 Mr. Frank Tedeschi, Church Publishing, Staff/Consultant New York The Rev. H. Lawrence Thompson, Resigned Pittsburgh, 2009 Ms. Jessica Wilkerson Montana, 2009 Mr. Ted Yumoto, Executive Council Liason* San Joaquin, 2009 +Staff/Consultant **Appointed April 2008 to fulfill term of H. Lawrence Thompson COMMISSION MEETING DATES November 15-19, 2006, Chicago, Illinois; May 7-10, 2007, Menlo Park, California; September 26-29, 2007, New Orleans, Louisiana; February 2008, Memphis, Tennessee; May 19-22, 2008, Federal Way, Washington; October 13-17, 2008, Ashland, Nebraska COMMITTEE/PROJECT REPORTS Rachel’s Tears, Hannah’s Hopes: Liturgies and Prayers for Healing from Loss Related to Childbearing and Childbirth Project Chair: The Rev. Devon Anderson Project Editor: Mrs. Phoebe Pettingell Project Consultants: Ms. April Alford, the Rev. Jennifer Baskerville Burrows, the Rev. Susan K. Bock (writer), Ms. Julia Huttar Bailey, the Very Rev. Cynthia Black, the Rev. -

“Wild Mobs, to Mad Sedition Prone”: Preaching the American Revolution Barry Levis Rollins College, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Marshall University Article Volume 3 | Number 1 3 “Wild Mobs, to Mad Sedition Prone”: Preaching the American Revolution Barry Levis Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sermonstudies Part of the Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Levis, Barry. "“Wild Mobs, to Mad Sedition Prone”: Preaching the American Revolution." Sermon Studies (Journal) 3.1 () : 19-39. https://mds.marshall.edu/sermonstudies/vol3/iss1/3 Copyright 2019 by Barry Levis This Original Article is brought to you by Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact the editor at [email protected] Levis: “Wild Mobs, to Mad Sedition Prone” “Wild Mobs, to Mad Sedition Prone”: Preaching the American Revolution R. Barry Levis While clergy in other denominations certainly preached about the conflicts between the American colonies and Great Britain, this paper will be focusing solely on the colonial clergy of the Church of England. Some significant differences existed between the Anglican clergy and other denominations. First, they had not come to the colonies because of perceived religious persecution. They were clergy of the Established Church whose supreme governor was the king. Secondly, unlike other clergy, they had taken an ordination oath of allegiance to the crown, which many high churchmen regarded as sacrosanct. The Church of England in the American colonies was really not a single institution. Because no local bishop governed the church in America, falling as it did under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London, the clergy tended to have differing loyalties. -

The Episcopal Church and the American Revolution

The Episcopal Church and the American Revolution David L. Holmes evolutions, like street fights," an Episcopal church historian has written, "are likely to be as dangerous to the innocent by- JL ^standers as to the participants."1 Technically speaking, the Ang- lican Church in America was an innocent bystander in the American Revo- lution. But since it lived in the neighborhood of one of the participants and was intimately related to the other, it emerged with a terrible beat- ing. The war raised questions of patriotism, of loyalty, and of the obliga- tions of Christians at a time of war, and Americans who have lived through the Civil War or the Vietnam War have been there. Distinguished from other denominations in the colonies by its triple attachment to the Book of Common Prayer, to the Monarchy, and to the Episcopate, the American transplantation of the Church of England seemed in good condition on the eve of the Revolution. Anglicanism- the terms 'Protestant Episcopal" or "Episcopal Church" were not officially adopted until the 1780's- was not only the second largest denomination in the thirteen colonies but also one that was increasing rapidly. Although the Anglican parishes had their problems, the question of survival ap- peared not to be one. Yet Anglicanism emerged from the Revolutionary War seriously weakened in most of the newly-independent states and on the point of extinction in others. In New England-a traditional stronghold of anti-Anglicanism, where Congregationalism was established by law in all colonies except Rhode Mr. Holmes is Associate Professor of Religion at the College of William and Mary and Visiting Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Virginia - Editors Note . -

Of the Pamphlet Collection of the Diocese

Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2012 witii funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/pamphletcOOcame INDEX OF THE PAMPHLET COLLECTION OF thp: DIOCESE OF CONNECTICUT By KENNETH WALTER CAMERON ARCHIVIST AND HISTOKKKIKAI'HKK THE HISTORIOGRAPHER DRAWER 1080 HARTFORD 1, CONN. 1958 To ARTHUR ADAMS A Distinguished Scholar, Educator And Prefjbyter "Honestus rumor alterum patrimonitun est," Prefiace This oltmo will provlda a short-title list of the 3,000 tracts (some of them duplicates) in the first one hundred and eighty-eight volumes in the Archiyas of the Diocese of Connecticut, housed in the Trinity College Library in Hartford. Their value to the student of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries cannot be overemphasized, since the political, literary and apologetical Issues of those periods were largely debated and won in pamphlet warfare. The Church historian, moreover, is so much indebted to early leaflets for many basic facts that an analyzed collection of this kind must invariably stimulate research in the department of parochial origins and growth. The original plan called for a terminal cross-reference index of parishes, persons, issues and themes, but lack of opportunity made that part of the proj- ect impossible at this time, (it may, of course, be undertaken later on as a separate venture.) The compilation as it stands is divisible into three sec- tions! Pages I. The Main Index, arranged by authors or principal subjects 3-156« II* Addenda to the Main Index 157-158, III. Index of Titles for which authorship could not be established 158-169. I am indebted to my Trinity College students for help with the task at various stages.