U.S. Policy in Colombiadownload

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislating During War: Conflict and Politics in Colombia

Legislating During War: Conflict and Politics in Colombia Juan S. Morales∗ Collegio Carlo Alberto University of Turin July 24, 2020 Abstract This paper studies how politicians and their constituents respond to political violence by investigating the case of the Colombian civil conflict. I use data on rebel attacks, legislators’ tweets and roll-call votes, and I employ event study and difference-in-differences empirical methods. Twitter engagement (as a proxy for popular support) increases after rebel attacks for both incumbent party legislators and for tweets with a "hard-line" language. Legislators increase their support for the incumbent party after attacks, but only when the government has a hard-line policy position, as inferred both from the recent historical context and from text analysis of the president’s tweets. Though the effects are initially large they last less than two weeks. The empirical results are consistent with a political economy model of legislative behaviour in which events that shift voters’ views, and the presence of rally ‘round the flag effects, elicit different politician responses depending on the policy position of the incumbent party. Finally, I identify a set of potentially affected congressional votes, suggesting that these conflict-induced swings in incumbent support can have persistent policy consequences. JEL Codes: D72;D74;H56;O10 Keywords: civil conflict; legislative decision-making; roll-call votes; political language; social media ∗Collegio Carlo Alberto, Piazza Arbarello 8, 10122, Torino, TO, Italy (e-mail: [email protected]). I thank the editor, Maria Petrova, and anonymous referees for their careful reviews and suggestions. I am grateful to Gustavo Bobonis, Albert Berry, Marco Gonzalez-Navarro and Michel Serafinelli for their guidance and support. -

Colombia's National Law of Firearms and Explosives

COLOMBIA ’S NATIO N AL LAW OF FIREARMS A N D EXPLOSIVES by Jonathan Edward Shaw* IP-3-2011 May 2011 13952 Denver West Parkway • Suite 400 • Golden, Colorado 80401-3141 www.IndependenceInstitute.org • 303-279-6536 • 303-279-4176 fax COLOM bia ’S NA T I ON A L LA W OF FI RE A RMS A ND EXPLOS I VES Abstract: This Issue Paper provides English translations The translations included in this Issue Paper are based of Colombian gun control statutes and the arms-related on the original Spanish versions of the Colombian provisions of Colombia’s present and past constitutions. The Constitution and the laws that govern gun control in Issue Paper also provides a history of the arms provisions in Colombia. I have made my best effort to translate Colombia’s constitutions over the last two centuries, and in the documents into English, rather than re-writing the the Spanish law that preceded them. In addition to translating documents as if they had originally been written in English. the modern gun control statutes, the Issue Paper presents a My purpose was to clearly communicate the content narrative explanation of the most important provisions. From of the documents and to avoid modifying meanings to colonial days to the present, Colombian law has presumed facilitate modern English wording. For example, the that many Colombians will own and carry firearms for Spanish word municiones might normally be translated sports and for self-defense. Contemporary laws continue this as ammunition in English; however I have used the word tradition, in the context of a system of regulation. -

Colombia's Constitution of 1991 with Amendments Through 2015

PDF generated: 16 Sep 2021, 17:03 constituteproject.org Colombia's Constitution of 1991 with Amendments through 2015 Subsequently amended © Oxford University Press, Inc. Translated by Max Planck Institute, with updates by the Comparative Constitutions Project Prepared for distribution on constituteproject.org with content generously provided by Oxford University Press. This document has been recompiled and reformatted using texts collected in Oxford’s Constitutions of the World and the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 16 Sep 2021, 17:03 Table of contents Preamble . 4 TITLE I: On Fundamental Principles . 4 TITLE II: On Rights, Guarantees, and Duties . 5 Chapter I: On Fundamental Rights . 5 Chapter II: On Social, Economic, and Cultural Rights . 10 Chapter III: On Collective Rights and the Environment . 20 Chapter IV: On the Protection and Application of Rights . 21 Chapter V: On Duties and Obligations . 23 TITLE III: On the Population and the Territory . 24 Chapter I: On Nationality . 24 Chapter II: On Citizenship . 25 Chapter III: On Aliens . 25 Chapter IV: On Territory . 25 TITLE IV: On Democratic Participation and Political Parties . 26 Chapter I: On the Forms of Democratic Participation . 26 Chapter II: On Political Parties and Political Movements . 27 Chapter III: On the Status of the Opposition . 30 TITLE V: On the Organization of the State . 31 Chapter I: On the Structure of the State . 31 Chapter II: On the Public Service . 32 TITLE VI: On the Legislative Branch . 35 Chapter I: On its Composition and Functions . 35 Chapter II: On its Sessions and Activities . 38 Chapter III: On Statutes . -

National Administrative Department of Statistics

NATIONAL ADMINISTRATIVE DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS Methodology for the Codification of the Political- Administrative Division of Colombia -DIVIPOLA- 0 NATIONAL ADMINISTRATIVE DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS JORGE BUSTAMANTE ROLDÁN Director CHRISTIAN JARAMILLO HERRERA Deputy Director MARIO CHAMIE MAZZILLO General Secretary Technical Directors NELCY ARAQUE GARCIA Regulation, Planning, Standardization and Normalization EDUARDO EFRAÍN FREIRE DELGADO Methodology and Statistical Production LILIANA ACEVEDO ARENAS Census and Demography MIGUEL ÁNGEL CÁRDENAS CONTRERAS Geostatistics ANA VICTORIA VEGA ACEVEDO Synthesis and National Accounts CAROLINA GUTIÉRREZ HERNÁNDEZ Diffusion, Marketing and Statistical Culture National Administrative Department of Statistics – DANE MIGUEL ÁNGEL CÁRDENAS CONTRERAS Geostatistics Division Geostatistical Research and Development Coordination (DIG) DANE Cesar Alberto Maldonado Maya Olga Marina López Salinas Proofreading in Spanish: Alba Lucía Núñez Benítez Translation: Juan Belisario González Sánchez Proofreading in English: Ximena Díaz Gómez CONTENTS Page PRESENTATION 6 INTRODUCTION 7 1. BACKGROUND 8 1.1. Evolution of the Political-Administrative Division of Colombia 8 1.2. Evolution of the Codification of the Political-Administrative Division of Colombia 12 2. DESIGN OF DIVIPOLA 15 2.1. Thematic/methodological design 15 2.1.1. Information needs 15 2.1.2. Objectives 15 2.1.3. Scope 15 2.1.4. Reference framework 16 2.1.5. Nomenclatures and Classifications used 22 2.1.6. Methodology 24 2.2 DIVIPOLA elaboration design 27 2.2.1. Collection or compilation of information 28 2.3. IT Design 28 2.3.1. DIVIPOLA Administration Module 28 2.4. Design of Quality Control Methods and Mechanisms 32 2.4.1. Quality Control Mechanism 32 2.5. Products Delivery and Diffusion 33 2.5.1. -

Colombia.Pdf

INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION 124th Assembly and related meetings Panama City (Panama), 15 - 20 April 2011 Governing Council CL/188/13(b)-R.2 Item 13(b) Panama City, 15 April 2011 COMMITTEE ON THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF PARLIAMENTARIANS REPORT OF THE DELEGATION MISSION TO COLOMBIA, 9 TO 13 OCTOBER 2010 COLOMBIA 1. CASE No. CO/01 - PEDRO NEL JIMÉNEZ OBANDO CASE No. CO/02 - LEONARDO POSADA PEDRAZA CASE No. CO/03 - OCTAVIO VARGAS CUÉLLAR CASE No. CO/04 - PEDRO LUIS VALENCIA GIRALDO CASE No. CO/06 - BERNARDO JARAMILLO OSSA CASE No. CO/08 - MANUEL CEPEDA VARGAS CASE No. CO/09 - HERNÁN MOTTA MOTTA 2. CASE No. CO/07 - LUIS CARLOS GALÁN SARMIENTO 3. CASE No. CO/121 - PIEDAD CÓRDOBA 4. CASE No. CO/140 - WILSON BORJA 5. CASE No. CO/142 - ALVARO ARAÚJO CASTRO 6. CASE No. CO/145 - LUIS HUMBERTO GÓMEZ GALLO 7. CASE No. CO/146 - IVAN CEPEDA INDEX Page A. Background, purpose and conduct of the mission ...................................... 2 B. Programme of the mission ........................................................................... 2 C. Summary of information received before the departure of the mission........ 3 D. Information gathered during the mission ..................................................... 6 E. Conclusions ................................................................................................ 13 CL/188/13(b)-R.2 - 2 - Panama City, 15 April 2011 A. BACKGROUND, PURPOSE AND CONDUCT OF THE MISSION 1. The Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians is examining several cases of violations of the human rights of incumbent and former members of the National Congress of Colombia. The focus in these cases is on three main concerns. The first was provided by the murder of six Congress members between 1986 and 1994, all belonging to the Unión Patriótica (Patriotic Union party), and of the liberal senator Mr. -

15 the Story of the Us Role in the Killing of Pablo Escobar

15 THE STORY OF THE U.S. ROLE IN THE KILLING OF PABLO ESCOBAR Mark Bowden American military interventions overseas frequently have the inadvertent side effect of mobilizing anti- American sentiment. In Vietnam, Somalia, Nicaragua, Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere, the presence of uniformed American soldiers has energized propagandists who portrayed the American effort—including humanitarian missions like the one in Somalia in the early 1990s—as imperialist, an effort to impose West- ern values or American rule. In some instances, this blowback can severely undermine and even defeat U.S. objectives. As a result, it is often preferable for interventions to remain covert, even if they are successful. The killing of Colombian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar in 1993 offers a good example of both the virtues and hazards of working undercover with indigenous foreign forces. This chapter provides background on Pablo Escobar and his Medellin Cartel, including how Escobar achieved notoriety and power in Colombia. It then details Centra Spike, a U.S. Army signals intelligence unit that assisted the National Police of Colombia in finding Escobar and other Colombian drug lords. Although American assistance eventually led to the deaths of Escobar and other drug kingpins, it raised a number of legal and ethical challenges that are discussed in this chapter. Pablo Escobar and the Colombian drug trade During the 1970s and early 1980s, there was an increasing flow of cocaine from Colombia to the United States. A sizeable portion of an American generation reared on smoking dope and dropping acid had matured with an appetite for “uppers” and cocaine, which briefly became fashionable with young white professionals. -

General Law for Culture

DISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations,GENERAL hyperlinks and LAWexplanatory FOR notes CULTURE (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-dating on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved.This information may be used only for research, educational, legal and non- commercial purposes, with acknowledgement of UNESCO Cultural Heritage Laws Database as the source (© UNESCO). LAW 397 OF 1997 By way of which articles 70, 71 and 72 are developed and all other articles in agreement with the Political Constitution, and regulations are enacted on Cultural Heritage, on culture promotion and incentives, the Ministry of Culture is created and some offices are relocated. REPUBLIC OF COLOMBIA ANDRÉS PASTRANA ARANGO President ROMULO GONZALEZ TRUJILLO Ministry of Justice and Laws 1 DISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations, hyperlinks and explanatory notes (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-dating on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. COPYRIGHT:LAW All right 397s reserved.This OF 1997 information may be used only for research, educational, legal and non- commercial purposes, with acknowledgement of UNESCO Cultural Heritage Laws Database as the source (© UNESCO). (August 7) By way of which articles 70, 71 and 72 are developed and all other articles in agreement with the Political Constitution, and regulations are enacted on Cultural Heritage, on culture promotion and incentives , the Ministry of Culture is created and some offices are relocated. The Congress of Colombia DECREES: TITLE I Fundamental Principles and definitions Article 1. -

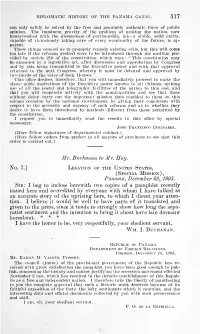

Diplomatic History of the Panama Canal.: Correspondence Relating to the Negotiation and Application of Certain Treaties on the S

: DIPLOMATIC HISTORY OF THE PANAMA CANAL. 517 can only safely be solved by the free and genuinely authentic force of public opinion. The imminent gravity of tbe problem of making the nation, now honeycombed with the dissensions of partisanship, into a stable, solid entity, capable of victoriously taking care of every eventuality of the future, is ap- parent. These things counsel us to promptly remedy existing evils, but this will come too late if the reforms desired were to be introduced through the medium pro- " vided by article 210 of the constitution, which says : This constitution may be amended by a legislative act. after discussion and approbation by Congress and by this being transmitted to the Executive power and with that approval returned to the next Congress, wherein it must be debated and approved by two-thirds of the votes of both Houses." This office desires, therefore, that you will immediately proceed to make the above noble aspirations of the Executive power known to all citizens, making use of all the postal and telegrapbic facilities of the nation to this end, and that you will cooperate actively with the municipalities and see that these without delay carry out the important mission thus confided to them on this solemn occasion by the national Government, by giving their conclusion with respect to the necessity and urgency of such reforms and as to whether they desire to have them introduced by methods different from those permitted by the constitution. I request you to immediately send the results to this office by special messenger. -

Mr Eduardo Cifuentez Muñoz CV ENG 02Sep 1630

Personal details Name: Eduardo Cifuentez Muñoz Place and date of birth: Popayán (Colombia), March 24 1954 Languages: English, French, Italian, Spanish, Positions: -Former Justice and President of the Colombian Constitutional Court (1991- 2000) -Former Ombudsperson of Colombia (2000 - 2003) -Former Director of the Human Rights Division at UNESCO (2003 - 2005). Academic record University Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia. Juris Doctor, 1977. Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain. Diploma in Advanced Studies in Law. Columbia University, Parker School of Foreign and Comparative Law, New York, United States of America, June 1984. Postgraduate academic experience Lecturer in private and constitutional law at the Universidad de los Andes-Law School, for 15 years. Founder and Director of several postgraduate programs at the Universidad de los Andes-Law School. Founder and member of the editorial board of the Public and Private Law Journals published by Universidad de los Andes- Law School. Founder and member of the editorial board of the Economic Law Journal, published by the Economic Law Association. Member of the Advisory Committee of the Judiciary Academy Journal, Lima, Perú. Professional experience March 2011 – present Los Andes University Associate Professor of Law. March 2005 – February 2011 Los Andes University Dean of the School of Law. September 2003 – February 2005 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Director of the Human Rights Division. President of the Andean Council of Ombduspersons (Defensores del Pueblo). September 2000 - August 2003 Colombian Ombudsperson (Defensor del Pueblo). November 1991- August 2000 Constitutional Court: - Justice - President (1999). April 1986 - November 1991 Banco de Colombia Legal and Financial Vice-president. April 1983 - March 1986 Los Andes University Coordinator, Postgraduate Degree in Financial Legislation. -

Conflict and Politics in Colombia

Legislating during war: Conflict and politics in Colombia Juan S. Morales∗ University of Toronto June 14, 2017 Abstract For many countries, the escape from weak governance and cycles of violence is today the most challeng- ing step in their path to prosperity. This paper studies an important aspect of this challenge: the relationship between civil conflict and congressional decision-making. I study this relationship in the context of Colom- bia, an electoral democracy that has endured the longest conflict in the Americas. More specifically, I exam- ine how politicians and their constituents respond to attacks by FARC, Colombia’s largest rebel group. To measure these responses, I use data from politicians’ Twitter accounts and roll-call voting records, and em- ploy both an event study and a difference-in-differences research design which exploit the high-frequency nature of the data. I use text analysis to measure the "political leaning" of politicians’ tweets, and find that both tweets from incumbent politicians and tweets which exhibit "right-wing" language receive higher user engagement (a proxy for popular support) following rebel attacks. The legislative decision-making responses are more complex. Before the government started a peace process with the rebels in 2012, politi- cians in congress were more likely to align their legislative votes with the right-leaning ruling party in the days following an attack. However, this relationship breaks down during the negotiations. In addition, politicians are more responsive to attacks which occur in their electoral district. The empirical results are consistent with a political economy model of legislative behaviour in which events that shift median voter preferences, and the presence of rally ’round the flag effects, elicit different politician responses depending on the policy position of the ruling party. -

Truth-Telling and Internal Displacement in Colombia

Case Studies on Transitional Justice and Displacement Truth-Telling and Internal Displacement in Colombia Roberto Vidal-López July 2012 ICTJ/Brookings | Truth-Telling and Internal Displacement in Colombia Transitional Justice and Displacement Project From 2010-2012, the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) and the Brookings-LSE Project on Internal Displacement collaborated on a research project to examine the relationship between transitional justice and displacement. The project examined the capacity of transitional justice measures to respond to the issue of displacement, to engage the justice claims of displaced persons, and to contribute to durable solutions. It also analyzed the links between transitional justice and other policy interventions, including those of humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding actors. Please see: www.ictj.org/our-work/research/transitional-justice-and-displacement and www.brookings.edu/idp. About the Author Roberto Vidal-López is Associate Professor and Director of the Department of Philosophy and Legal History, Faculty of Law, at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá, Colombia. He specializes in human rights and migration issues, and has written extensively on issues of human rights, transitional justice, and displacement in Colombia. Acknowledgements ICTJ and the Brookings-LSE Project on Internal Displacement wish to thank the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA) and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT), which provided the funding that made this project possible. About ICTJ ICTJ assists societies confronting massive human rights abuses to promote accountability, pursue truth, provide reparations, and build trustworthy institutions. Committed to the vindication of victims’ rights and the promotion of gender justice, we provide expert technical advice, policy analysis, and comparative research on transitional justice measures, including criminal prosecutions, reparations initiatives, truth seeking, memorialization efforts, and institutional reform. -

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (Ratified by Act No

UNITED NATIONS CERD Distr. International Convention GENERAL on the Elimination of All CERD/C/COL/14 Forms of Racial 5 May 2008 Discrimination ENGLISH Original: SPANISH COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 9 OF THE CONVENTION Fourteenth periodic report of States parties due in 2008 Addendum COLOMBIA*, ** [29 February 2008] * This document contains the 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th periodic reports of Colombia, due on 2 October 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2008, respectively. For the 8th and 9th periodic reports of Colombia (consolidated document) and the summary records of the meetings at which the Committee considered those reports, see documents CERD/C/332/Add.1 and CERD/C/SR.1356, 1357 and 1362. ** In accordance with the information transmitted to the States parties regarding the processing of their reports, the present document was not formally edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.08-42184 (EXT) CERD/C/COL/14 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. BASIC INFORMATION ABOUT COLOMBIA................................... 1-45 3 A. Political organization..................................................................... 2-7 3 B. Territory......................................................................................... 8 4 C. Culture and religion ....................................................................... 9-11 4 D. Sociodemographic context ............................................................ 12-23 4 E.