Pakistan 2019 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Election 2018 Update-Ii - Fafen General Election 2018

GENERAL ELECTION 2018 UPDATE-II - FAFEN GENERAL ELECTION 2018 Update-II April 01 – April 30, 2018 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) initiated its assessment of the political environment and implementation of election-related laws, rules and regulations in January 2018 as part of its multi-phase observation of General Election (GE) 2018. The purpose of the observation is to contribute to the evolution of an election process that is free, fair, transparent and accountable, in accordance with the requirements laid out in the Elections Act, 2017. Based on its observation, FAFEN produces periodic updates, information briefs and reports in an effort to provide objective, unbiased and evidence-based information about the quality of electoral and political processes to the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), political parties, media, civil society organizations and citizens. General Election 2018 Update-II is based on information gathered systematically in 130 districts by as many trained and non-partisan District Coordinators (DCs) through 560 interviews1 with representatives of 33 political parties and groups and 294 interviews with representative of 35 political parties and groups over delimitation process. The Update also includes the findings of observation of 559 political gatherings and 474 ECP’s centres set up for the display of preliminary electoral rolls. FAFEN also documented the formation of 99 political alliances, party-switching by political figures, and emerging alliances among ethnic, tribal and professional groups. In addition, the General Election 2018 Update-II comprises data gathered through systematic monitoring of 86 editions of 25 local, regional and national newspapers to report incidents of political and electoral violence, new development schemes and political advertisements during April 2018. -

March 2019 Volume 10 Issue 3 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & Will Be Soon from UAE ”

March 2019 Volume 10 Issue 3 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 09 14 26 31 09 Pakistan’s highest civil honour “Our Pakistani brothers participated truthfully and effectively in the great development project that Saudi Arabia witnessed, especially the “Nishan-e-Pakistan” enlargement project of Masjid-e-Haram and Masjid-e-Nabwi. More than 2 Conferred upon million Pakistanis are working in Saudi Arabia and are contributing to the development of both the countries. Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman 14 Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, no doubt, has emerged as one of the most popular foreign leaders in Pakistan because of his highly laudable The most popular foreign leader in pronouncements made during his crucial visit to Islamabad and sentiments of love, affection and care expressed for Pakistani state and its people. By Pakistan expressing his determination, while wrapping up his historic tour, to make efforts to reduce tension between Pakistan and India, MBS conveyed in clear-cut terms that he was keen to mitigate challenges of the country on every front. Pakistan has always been an ardent supporter of regional peace and 26 “TOGETHER FOR PEACE” collaborative security. As a torch bearer of this unflinching resolve, Pakistan Navy is spearheading numerous initiatives, and conduct of series of MULTINATIONAL MARITIME EXERCISE Multinational Maritime Exercise AMAN is one of the quantum leaps towards AMAN-2019 the fulfillment of this shared vision along with global partners. Pakistan Navy has been hosting Multinational Maritime Exercise AMAN biennially since 2007. 31 President of Pakistan confers NI (M) President Dr. -

Newsletter June 2021

–- 1 President Arif Alvi promotes research-oriented and innovation-based quality education in universities resident Dr Arif Alvi has called for promoting research-oriented and innovation-based quality P education in universities to overcome the scientific and technological challenges faced by the country. He emphasised the need to educate the students about the latest technological trends in order to meet the requirements of the 4th Industrial Revolution. The President made these remarks at a briefing on Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), given by Rector LUMS, Mr Shahid Hussain, at Aiwan-e-Sadr, on June 14, 2021. Addressing the meeting, the Presi- dent underlined the need for promotion of online education as it was cost-effective and accessible to students belonging to the far flung areas of the country and under-privileged strata of society. He urged the universities to initiate steps to encourage e-learning as it played an instrumental role in ensuring continuity of education during the COVID-19 pandemic. President condoles with family killed in terrorist attack in Canada’s London Ontario resident Dr Arif Alvi and Begum Samina Alvi P visited the resi- dence of bereaved family of Pakistani origin victims of the terrorist attack in Ontario, Canada, to express their condolence. The president expressed his sympathies with the bereaved family over the loss, a press release said. The president and Begum Alvi offered Fateha and prayed for the departed soul and for the bereaved family to bear the loss with equanimity. 2 Prime Minister Imran Khan urges world leaders to act against Islamophobia rime Minister Imran Khan has called upon the world P leaders to crack down on online hate speech and Islamophobia following the deadly truck attack in London, Ontario, Canada. -

The Terrorism Trap: the Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2019 The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror John Akins University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Akins, John, "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by John Akins entitled "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Krista Wiegand, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Brandon Prins, Gary Uzonyi, Candace White Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America’s War on Terror A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville John Harrison Akins August 2019 Copyright © 2019 by John Harrison Akins All rights reserved. -

STATE of CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS in PAKISTAN a Study of 5 Years: 2013-2018

STATE OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN PAKISTAN A Study of 5 Years: 2013-2018 Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency STATE OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN PAKISTAN A Study of 5 Years: 2013-2018 Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency PILDAT is an independent, non-partisan and not-for-profit indigenous research and training institution with the mission to strengthen democracy and democratic institutions in Pakistan. PILDAT is a registered non-profit entity under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, Pakistan. Copyright © Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency - PILDAT All Rights Reserved Printed in Pakistan Published: January 2019 ISBN: 978-969-558-734-8 Any part of this publication can be used or cited with a clear reference to PILDAT. Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency Islamabad Office: P. O. Box 278, F-8, Postal Code: 44220, Islamabad, Pakistan Lahore Office: P. O. Box 11098, L.C.C.H.S, Postal Code: 54792, Lahore, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] | Website: www.pildat.org P I L D A T State of Civil-Military Relations in Pakistan A Study of 5 Years: 2013-2018 CONTENTS Preface 05 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 07 Executive Summary 09 Introduction 13 State of Civil-military Relations in Pakistan: June 2013-May 2018 13 Major Irritants in Civil-Military Relations in Pakistan 13 i. Treason Trial of Gen. (Retd.) Pervez Musharraf 13 ii. The Islamabad Sit-in 14 iii. Disqualification of Mr. Nawaz Sharif 27 iv. 21st Constitutional Amendment and the Formation of Military Courts 28 v. Allegations of Election Meddling 30 vi. -

Police Organisations in Pakistan

HRCP/CHRI 2010 POLICE ORGANISATIONS IN PAKISTAN Human Rights Commission CHRI of Pakistan Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative working for the practical realisation of human rights in the countries of the Commonwealth Human Rights Commission of Pakistan The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) is an independent, non-governmental organisation registered under the law. It is non-political and non-profit-making. Its main office is in Lahore. It started functioning in 1987. The highest organ of HRCP is the general body comprising all members. The general body meets at least once every year. Executive authority of this organisation vests in the Council elected every three years. The Council elects the organisation's office-bearers - Chairperson, a Co-Chairperson, not more than five Vice-Chairpersons, and a Treasurer. No office holder in government or a political party (at national or provincial level) can be an office bearer of HRCP. The Council meets at least twice every year. Besides monitoring human rights violations and seeking redress through public campaigns, lobbying and intervention in courts, HRCP organises seminars, workshops and fact-finding missions. It also issues monthly Jehd-i-Haq in Urdu and an annual report on the state of human rights in the country, both in English and Urdu. The HRCP Secretariat is headed by its Secretary General I. A. Rehman. The main office of the Secretariat is in Lahore and branch offices are in Karachi, Peshawar and Quetta. A Special Task Force is located in Hyderabad (Sindh) and another in Multan (Punjab), HRCP also runs a Centre for Democratic Development in Islamabad and is supported by correspondents and activists across the country. -

CRSS Annual Security Report 2017

CRSS Annual Security Report 2017 Author: Muhammad Nafees Editor: Zeeshan Salahuddin Table of Contents Table of Contents ___________________________________ 3 Acronyms __________________________________________ 4 Executive Summary __________________________________ 6 Fatalities from Violence in Pakistan _____________________ 8 Victims of Violence in Pakistan________________________ 16 Fatalities of Civilians ................................................................ 16 Fatalities of Security Officials .................................................. 24 Fatalities of Militants, Insurgents and Criminals .................. 26 Nature and Methods of Violence Used _________________ 29 Key militants, criminals, politicians, foreign agents, and others arrested in 2017 ___________________________ 32 Regional Breakdown ________________________________ 33 Balochistan ................................................................................ 33 Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) ......................... 38 Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (KP) ....................................................... 42 Punjab ........................................................................................ 47 Sindh .......................................................................................... 52 Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), Islamabad, and Gilgit Baltistan (GB) ............................................................................ 59 Sectarian Violence .................................................................... 59 3 © Center -

PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST a Selected Summary of News, Views and Trends from Pakistani Media

February 2017 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST A Selected Summary of News, Views and Trends from Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr Ashish Shukla & Nazir Ahmed (Research Assistants, Pakistan Project, IDSA) PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST FEBRUARY 2017 A Select Summary of News, Views and Trends from the Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr Ashish Shukla & Nazir Ahmed (Pak-Digest, IDSA) INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES 1-Development Enclave, Near USI Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 Pakistan News Digest, February (1-15) 2017 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST, FEBRUARY 2017 CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 0 ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................... 2 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS ............................................................................. 3 NATIONAL POLITICS ....................................................................................... 3 THE PANAMA PAPERS .................................................................................... 7 PROVINCIAL POLITICS .................................................................................... 8 EDITORIALS AND OPINION .......................................................................... 9 FOREIGN POLICY ............................................................................................ 11 EDITORIALS AND OPINION ........................................................................ 12 MILITARY AFFAIRS ............................................................................................. -

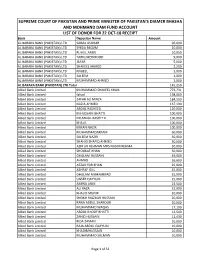

22-10-2018.Pdf

SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN AND PRIME MINISTER OF PAKISTAN'S DIAMER BHASHA AND MOHMAND DAM FUND ACCOUNT LIST OF DONOR FOR 22 OCT-18 RECEIPT Bank Depositor Name Amount AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SAIMA ASGHAR 96,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SYEDA BEGUM 20,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD RUHUL AMIN 10,050 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD TARIQ MEHMOOD 9,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD JAFAR 5,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SHAKEEL AHMED 2,200 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD NABEEL 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SALEEM 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD MUHAMMAD AHMED 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD Total 145,250 Allied Bank Limited MUHAMMAD SHAKEEL KHAN 773,731 Allied Bank Limited fahad 198,000 Allied Bank Limited ZAFAR ALI MIRZA 184,500 Allied Bank Limited NAZIA AHMED 137,190 Allied Bank Limited ABDUL RASHEED 120,000 Allied Bank Limited M HUSSAIN BHATTI 100,000 Allied Bank Limited DR.ABDUL RASHEED 100,000 Allied Bank Limited KHALIL 100,000 Allied Bank Limited IMRAN NAZIR 100,000 Allied Bank Limited MUHAMMADAKRAM 60,000 Allied Bank Limited SALEEM NAZIR 50,000 Allied Bank Limited SHAHID SHAFIQ AHMED 50,000 Allied Bank Limited AZIR UR REHMAN MRS NASIM REHMA 50,000 Allied Bank Limited SHOUKAT KHAN 50,000 Allied Bank Limited GHULAM HUSSAIN 49,000 Allied Bank Limited AHMAD 26,600 Allied Bank Limited AEZAD YAR KHAN 25,000 Allied Bank Limited ASHRAF GILL 25,000 Allied Bank Limited GHULAM MUHAMMAD 25,000 Allied Bank Limited UNSER QAYYUM 25,000 Allied Bank Limited AMINA ASIM 23,500 Allied Bank Limited ALI RAZA 23,000 Allied Bank -

2011.10.00 Pakistans Law Enforcement Response Final.Pdf

1 Telephone: +92-51-2601461-2 Fax: +92-51-2601469 Email: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org This report was produced by the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime, Country Office, Pakistan. This is not an official document of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers and boundaries. The information contained in this report has been sourced from publications, websites, as well as formal and informal consultations. The analysis is not definitive. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................3 Abbreviations .........................................................................................................................5 About the Authors ..................................................................................................................6 Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................7 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 8 Key findings ...................................................................................................................... -

ISLAMABAD, TUESDAY, JULY 7, 2020 PART I Acts, Ordinances

PART I] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 7, 2020 425 ISLAMABAD, TUESDAY, JULY 7, 2020 PART I Acts, Ordinances, President’s Orders and Regulations GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN LAW AND JUSTICE DIVISION Islamabad, the 7th July, 2020 No. F. 2(1)/2020-Pub.—The following Ordinance Promulgated on 7th July, 2020 by the President is hereby published for general information:— ORDINANCE NO. VII OF 2020 AN ORDINANCE further to amend the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority Ordinance, 2002 WHEREAS, it is expedient further to amend the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority Ordinance, 2002 (XXII of 2002), for the purposes hereinafter appearing; AND WHEREAS the Senate and the National Assembly are not in session and the President is satisfied that circumstances exist which render it necessary to take immediate action; (425) [5688(2020)/Ex Gaz.] Price : Rs. 6.00 426 THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 7, 2020 [PART I NOW, THEREFORE, in exercise of the powers conferred by clause (1) of Article 89 of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is pleased to make and promulgate the following Ordinance:— 1. Short title and commencement.—(1) This Ordinance shall be called the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (Amendment) Ordinance, 2020. (2) It shall come into force at once. 2. Amendment in long title, Ordinance XXII of 2002.—In the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority Ordinance, 2002 (XXII of 2002), hereinafter called as the said Ordinance, in the long title, for the word “and” a comma shall be substituted and after the word “ works”, the words “and disposal of public assets” shall be inserted. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos