Fluid Form Esbjerg Art Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evening with Alexis Rockman

Press Release Bruce Museum Presents Can Art Drive Change on Climate Change? An Evening with Alexis Rockman Acclaimed artist to be joined by David Abel, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The Boston Globe 6:30 – 8:30 pm, December 5, 2019 Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Connecticut Alexis Rockman, The Farm, 2000. Oil and acrylic on wood panel, 96 x 120 in. GREENWICH, CT, November 4, 2019 — On Thursday, December 5, 2019, Bruce Museum Presents poses the provocative question “Can Art Drive Change on Climate Change?” Leading the conversation is acclaimed artist and climate-change activist Alexis Rockman, who will present specially chosen examples of his work and discuss how, and why, he uses his art to sound the alarm about the impending global emergency. Adding insight and his own expert perspective is The Boston Globe’s David Abel, who since 1999 has reported on war in the Balkans, unrest in Latin America, national security issues in Washington D.C., and climate change and poverty in New England. Page 1 of 3 Press Release Abel was also part of the team that won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News for the paper’s coverage of the Boston Marathon bombings. He now covers the environment for the Globe. Following Rockman’s presentation, Abel will join Rockman for a wide-ranging dialogue at the intersection of art and environmental activism, followed by question-and-answer session with the audience. Among the current generation of American artists profoundly motivated by nature and its future—from the specter of climate change to the implications of genetic engineering—Rockman holds an unparalleled place of honor. -

Carl Krull Has Made a Series of 22 Incredible Drawings for His Second Solo Show Seismic at V1 Gallery. Six of the Drawings Where

V1 GALLERY PROUDLY PRESENTS SEISMIC A SOLO EXHIBITION BY CARL KRULL OPENING: FRIDAY SEPTEMBER 26.09 2014. TIME: 17.00 - 22.00 EXHIBITION PERIOD SEPTEMBER 27 – OCTOBER 25. 2014. Carl Krull has made a series of 22 incredible drawings for his second solo show Seismic at V1 Gallery. Six of the drawings where made from the passenger seat on a road- trip across the United States in 2013. As a human seismograph he sat with the paper rolled around a tube drawing one line after another, incorporating or letting every bump in the road affect the flow of lines. The drawings becoming topographical maps of the journey and their creation. In an almost sculptural manner, Carl Krull seems to break with the two-dimensional surface of the paper. He employs drawing techniques that simultaneously act as obstructions and potential. The obsessiveness of the line work is an ongoing exploration. Rather than having contours that outlines a subject, an abundance of lines seems to protrude the subject. As a spectator your eye is constantly on the move. Your eyes start a journey following a straight line from the edge of the paper, moving horizontally towards the center, the line rises – sometimes thickens – and falls back down before it makes a turn in the shape of an eye and runs back parallel with itself to return to the edge of the paper just below its starting point. Faces and shapes resembling natural phenomenons such as tree rings and stalactite caves press through this grit of lines in playful and whimsical shifts. They are in a constant flux of change as in a state of dissolution and creation, being and not being. -

The Rhetorical Limits of Visualizing the Irreparable 1 - 7 Nature of Global Climate Change Richard D

Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment Selected Papers from the Conference held at DePaul University, Chicago, IL, June 22-25, 2007 Editors: Barb Willard DePaul University Chris Green DePaul University Host: DePaul University, College of Communication Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment DePaul University, Chicago, IL, June 22-25, 2007 Edited by: Barbara E. Willard Chris Green College of Communication Humanities Center DePaul University DePaul University Editorial Assistant: Joy Dinaro College of Communication DePaul University Arash Hosseini College of Communication DePaul University Publication Date: August 11, 2008 Publisher of Record: College of Communication, DePaul University, 2320 N. Kenmore Ave., Chicago, IL 60614 (773)325-2965 Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture: Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment Barb Willard and Chris Green, editors Table of Contents i - iv Conference Program vi-xii Preface and Acknowledgements xiii – xvi Twenty-Five Years After the Die is Cast: Mediating the Locus of the Irreparable From Awareness to Action: The Rhetorical Limits of Visualizing the Irreparable 1 - 7 Nature of Global Climate Change Richard D. Besel, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Love, Guilt and Reparation: Rethinking the Affective Dimensions of the Locus of the 8 - 13 Irreparable Renee Lertzman, Cardiff University, UK Producing, Marketing, Consuming & Becoming Meat: Discourse of the Meat at the Intersections of Nature and Culture Burgers, Breasts, and Hummers: Meat and Masculinity in Contemporary Television 14 – 24 Advertisements Richard A. -

Astrid Kruse Jensen Between the Real and the Imaginary

Dans le cadre du XVIIIe festival Les Boréales Un festival en Nord L’Artothèque de Caen présente du 13 novembre au 23 décembre 2009 Astrid Kruse Jensen Between the real and the imaginary © Astrid Kruse Jensen, Looking out, photographie, 2006 Artothèque de Caen Hôtel d’Escoville Place Saint-Pierre 14000 Caen Tel : 02 31 85 69 73 Fax : 02 31 86 53 57 [email protected] http://www.artotheque-caen.net Exposition Astrid Kruse Jensen Between the real and the imaginary du 13 novembre au 23 décembre 2009 À l’occasion de la XVIIIème édition du festival Les Boréales Un festival en Nord, l’Artothèque de Caen présente du 13 novembre au 23 décembre 2009, les photographies d’Astrid Kruse Jensen. Je recrée des scènes imaginaires qui auraient pu exister dans certains lieux. Qu’est- ce qui est réel ? Il est impossible de différencier notre réalité subjective de la réalité commune. Nous sommes toujours avec notre propre réalité. Astrid Kruse Jensen Photographe d’origine danoise vivant à Copenhague, Astrid Kruse Jensen fait ses études à la prestigieuse Académie Gerrit Rietveld à Amsterdam, puis à l’école des Beaux-Arts de Glasgow en Ecosse. Le travail en série fournit à l’artiste un terrain d’exploration, lui permettant de cerner ses préoccupations photographiques principales : le passage en- tre réalité, image et imagination, et la création de scénarios où tout cela peut prendre forme. Cette première exposition personnelle en France sera l’occasion de découvrir une sélection de photographies issues de trois de ses projets récents : Imaginary Realities, Parallel Landscapes et The Construction of memories. -

Wunderkammer 1 – Flydende Form

3 wunderkammer – en introduktion Dette hæfte introducerer den første udstilling i Esbjerg Kunstmu- 7 formen af strømmende vand seums treårige wunderkammer-projekt, Wunderkammer 1 – flyden- 10 dråbedynamik de form, som museets inspektør Christiane Finsen og direktør Inge 14 badekarshvirvlen Merete Kjeldgaard har kurateret i nært samarbejde med professor i fysik ved DTU, Tomas Bohr, og hans kolleger. 18 roterende polygoner 22 fl ydende objekter og overfl adespænding Hæftet indledes med en introduktion til både udstillingskonceptet 26 det hydrauliske spring og det videnskabelige område, som dette første wunderkammer 30 værkfortegnelse tager afsæt i: fluid dynamik. wunderkammer 1 wunderkammer 36 kunstnerbiografi er Tomas Bohr har genskabt laboratorieagtige opstillinger af fem af sine forsøg til projektet. Disse skanderer udstillingens enkelte afsnit og beskrives af Bohr et efter et. Hans tekster ledsages hver — gang af en præsentation af nogle af de kunstværker, som museets flydende form kuratorer har valgt til hvert eksperiment. Hæftet afsluttes med en værkfortegnelse og en kort beskrivelse af de involverede kunstnere. Når alle tre wunderkamre har været vist, udgiver Esbjerg Kunst- museum en velillustreret bog, der samler hele projektet og bringer både analyser af udstillingerne og resultater fra forskningen i, hvad publikum har oplevet. wunderkammer — en introduktion Christiane Finsen, museumsinspektør og Inge Merete Kjeldgaard, museumsdirektør ved Esbjerg Kunstmuseum Flydende form er den første udstilling i en serie af tre wunderkammer-udstillinger, som Esbjerg Kunstmuseum modtog Udstillingsprisen Vision for i 2017. Med prisen honorerer 1 wunderkammer Bikubenfonden en visionær idé, som kan “skabe rum for nytænkning af udstillings- formater med kunsten i centrum”, og som modtageren bagefter har mulighed for at realisere. -

ART FUNDAMENTALS 9-12, Fine and Performing Arts

ART FUNDAMENTALS 9-12, Fine and Performing Arts Developed By: Mrs. Angela Melchionne Effective Date: Fall 2021 Scope and Sequence: ● Unit 1: 2D Design: Elements & Principles of Art ● Unit 2: 2D Design: Drawing & Painting ● Unit 3: 3D Design: Ceramics & Sculpture ● Unit 4: Media Exploration & Portfolio Development Month Unit Activities/Assessments September Unit 1: 2D Design: Elements & ● Sketchbook, Journal, Accordion Book Development MP 1 ● Color Theory Principles ● Line, Value, Shape/Form, Color, Texture, Space ● Focal Point/Emphasis, Pattern, Balance, Movement/Rhythm, Unity, Contrast ● Art History & Criticism ● Building connections, relationships, and class culture ● Project Examples: Accordion Book, Radiant Word Self-Portrait, All About Me Self-Portrait, Zentangle, Neurographic Art ● Media Introductions: Pencil, Ink/marker, colored pencils, oil pastel, watercolor paint October Unit 1: 2D Design: Elements & ● Sketchbook, Journal, Accordion Book Development MP1 ● Color Theory Principles ● Composition using the Elements of Art (Line, Value, Shape/Form, Color, Texture, Space) ● Composition using the Principles of Design (Focal Point/Emphasis, Pattern, Balance, Movement/Rhythm, Unity, Contrast) ● Art History & Criticism ● Project Examples: Mandala, Texture Collage, Inktober, Sugar Skull ● Media/Technique Introductions: Value with pen/ink (hatching, cross hatching, stippling, etc.), Colored pencil (shading, blending, layering, etc.) November Unit 2: 2D Design: Drawing & ● Sketchbook, Journal, Accordion Book Development MP 2 ● Color Theory -

Lari Pittman

LARI PITTMAN Born 1952 in Los Angeles Lives and works in Los Angeles EDUCATION 1974 BFA in Painting from California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA 1976 MFA in Painting from California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Lari Pittman: Dioramas, Lévy Gorvy, Paris 2020 Iris Shots: Opening and Closing, Gerhardsen Gerner, Oslo Lari Pittman: Found Buried, Lehman Maupin, New York 2019 Lari Pittman: Declaration of Independence, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles 2018 Portraits of Textiles & Portraits of Humans, Regen Projects, Los Angeles 2017 Lari Pittman, Gerhardsen Gerner, Oslo Lari Pittman / Silke Otto-Knapp: Subject, Predicate, Object, Regen Projects, Los Angeles 2016 Lari Pittman: Grisaille, Ethics & Knots (paintings with cataplasms), Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin Lari Pittman: Mood Books, Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA Lari Pittman: Nocturnes, Thomas Dane Gallery, London Lari Pittman: NUEVOS CAPRICHOS, Gladstone Gallery, New York 2015 Lari Pittman: Homage to Natalia Goncharova… When the avant-garde and the folkloric kissed in public, Proxy Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles 2014 Lari Pittman: Curiosities from a Late Western Impaerium, Gladstone Gallery, Brussels 2013 Lari Pittman: from a Late Western Impaerium, Regen Projects, Los Angeles Lari Pittman, Bernier Eliades Gallery, Athens Lari Pittman, Le Consortium, Dijon, France Lari Pittman: A Decorated Chronology, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, MO 2012 Lari Pittman, Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin thought-forms, -

L.E.S. Gallery Evening Thursday, November 19, 4-8 Pm

L.E.S. Gallery Evening Thursday, November 19, 4-8 pm This coming Thursday, over 40 galleries on the Lower East Side will be open later to celebrate current exhibitions throughout the neighborhood. An interactive map is available here. 1969 Gallery frosch&portmann Off Paradise 56 HENRY GRIMM Pablo’s Birthday Andrew Edlin Gallery Helena Anrather Perrotin Arsenal Contemporary Art New James Cohan Peter Freeman, Inc. York James Fuentes LLC Pierogi ASHES/ASHES Kai Matsumiya Rachel Uffner Gallery ATM gallery NYC Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery RICHARD TAITTINGER GALLERY Bridget Donahue Krause Gallery Sargent’s Daughters Bureau LICHTUNDFIRE Shin Gallery carriage trade Lubov SHRINE Cristin Tierney Gallery M 2 3 signs and symbols David Lewis Magenta Plains Simone Subal Gallery DEREK ELLER GALLERY MARC STRAUS GALLERY Sperone Westwater Equity Gallery Martos Gallery The Hole FIERMAN McKenzie Fine Art Thomas Nickles Project Foxy Production Miguel Abreu Gallery Tibor de Nagy Gallery Freight+Volume Nathalie Karg Gallery Ulterior Gallery Front Room Gallery No Gallery Zürcher Gallery 1969 Gallery http://www.1969gallery.com 103 Allen Street INTERIORS: hello from the living room Amanda Barker, Johnny DeFeo, Lois Dodd, Gabrielle Garland, JJ Manford, John McAllister, Quentin James McCaffrey, Gretchen Scherer, Adrienne Elise Tarver, Ann Toebbe, Sophie Treppendahl, Brandi Twilley, Anna Valdez, Darryl Westly, Guy Yanai and Aaron Zulpo November 1 – November 29 56 HENRY https://56henry.nyc/ 56 Henry Street Richard Tinkler / Seven Paintings October 15 - November 25, 2020 56 HENRY shows seven paintings by Richard Tinkler. As if seen through a kaleidoscope or under the spell of deep meditation, the works often begin with a shared process before iterative reimagining delivers each to a novel conclusion. -

Introducing Bruce Museum Presents: Thought Leaders in Art and Science

Press Release Introducing Bruce Museum Presents: Thought Leaders in Art and Science Film producer and art collector Jennifer Blei Stockman inaugurates the Bruce Museum Presents series with a moderated conversation between contemporary women artists on Thursday, September 5. GREENWICH, CT, August 1, 2019 — Bruce Museum Presents is an exciting new series of monthly public programs featuring thought leaders in the fields of art and science. Showcasing experts on compelling subjects of relevance and interest to members and visitors to the Bruce Museum, as well as the communities of greater Fairfield County and beyond, Bruce Museum Presents launches on Thursday, September 5, 2019 at 6:00 pm, with Generation ♀: How Contemporary Women Artists Are Re-Shaping Today’s Art World. Jennifer Blei Stockman, producer of the Emmy-nominated 2018 HBO documentary The Price of Everything, moderates a wide-ranging dialogue and exploration with four major contemporary women artists: painter and sculptor Nicole Eisenman; conceptual visual artist Lin Jingjing; painter and sculptor Paula DeLuccia Poons; and photographer and filmmaker Laurie Simmons. Page 1 of 5 Press Release Background “Bruce Museum Presents inaugurates an exciting time of change and progress for this institution,” said Robert Wolterstorff, The Susan E. Lynch Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer. “As we prepare our expansion in order to become the region’s leading cultural center, the Bruce Museum is poised to present dynamic and unique educational programming equal to the caliber of our new spaces and collections.” Suzanne Lio, Managing Director of the Bruce Museum, conceived Bruce Museum Presents. “We have long been an important resource in our community for forward-thinking public programs,” Lio notes. -

The Pit Lmarkus CV 2021

Liz Markus b. 1967, Buffalo, NY Lives in Los Angeles, CA Education BFA, School of Visual Arts, New York, NY MFA, Tyler School of Art, Philadelphia, PA Solo and Two-Person Exhibitions 2021 Kermit, Kantor Gallery, Los Angeles, CA T Rex, The Pit, Glendale, CA 2020 Super Disco Disco Breakin’, Unit London, London, UK 2018 The Palm Beach Paintings, County Gallery, Palm Beach, FL 2017 Maruani Mercier Gallery, Brussels, BE 2014 Town & Country, Nathalie Karg Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Eleven, Ille Arts, Amagansett, NY The Look of Love, ZieherSmith, New York, NY 2010 Are You Punk Or New Wave? ZieherSmith, New York, NY 2009 Hot Nights At The Regal Beagle, ZieherSmith, New York, NY 2007 What We Are We’re Going To Wail With On This Whole Trip, Loyal Gallery, Stockholm, SWE The More I Revolt, The More I Make Love, ZieherSmith, New York, NY 2000 White Columns, New York, NY Group Exhibitions 2020 NADA 2020, The Pit, Los Angeles Six Hot and Glassy, with Katherine Bernhardt, Ashley Bickerton, Katherine Bradford, Mary Heilmann,Liz Markus, Dan McCarthy, Raymond Pettibon, Alexis Rockman, Lucien Smith, and Keith Sonnier, Tripoli Gallery, East Hampton Riders of The Red Horse, The Pit, Los Angeles 36 Paintings, Harper’s Books, East Hampton, NY 2019 YES., organized by Terry R. Myers, Patrick Painter Inc., Los Angeles Go Figure!, curated by Beth DeWoody, Eric Firestone Gallery, East Hampton, NY 2018 Fuigo, curated by Laura Dvorkin and Maynard Monrow, Fuigo, New York 2017 Man Alive, Jablonka Maruani Mercier Gallery, Brussels, Belgium, curated by Wendy White 2015 -

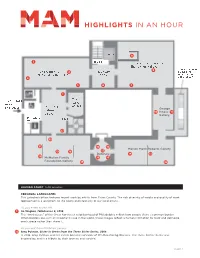

Highlights in an Hour

Bloomfield Avenue HIGHLIGHTS IN AN HOUR GALLERY LEVEL (2ND FLOOR) ELEVATOR 8 3 STAIR B Judy and Josh Weston Exhibition Gallery 9 The Blanche and Rand Gallery of 4 Elevator Irving Laurie Native American Art Lobby Foundation 2 Art Stairway 5 6 7 e u n e 1 v A n The i S.MOUNTAIN a t Store e n MUSEUM c a u at MAM Robert H. l o ENTRANCE GGeorgeeorge P M s Lehman Inness ’ h 10 Inness 11 e t Court k u Gallery Gallery u o L S Reception STAIR C . Desk t S 23 22 21 16 16 Marion Mann Roberts Gallery 15 McMullen Family F19oundati18on Gallery Rotunda Marion Mann Roberts Gallery Rotunda 14 13 20 McMullen Family 16 16 Foundation Gallery 17 12 PARKING LOT LEHMAN COURT 5-10 minutes PERSONAL LANDSCAPES This juried exhibition features recent work by artists from Essex County. The rich diversity of media and quality of work represented is a testament to the talent and creativity of our local artists. As you enter, to the left: 1 Ira Wagner, Twinhouses 3, 2018 The “twinhouses” of the Great Northeast neighborhood of Philadelphia reflect how people share a common border. When borders are such an important issue in the world, these images reflect a human inclination to mark and delineate one’s space rather than share it. As you exit from McMullen Gallery: 23 Amy Putman, Sister in Green from the Three Sister Series, 2018 In 2018, Amy Putman and her sisters became survivors of life-threatening illnesses. The Three Sisters Series was inspired by, and is a tribute to, their journey and survival. -

ART I 9-12, Fine and Performing Arts

ART I 9-12, Fine and Performing Arts Developed By: Angela Melchionne Effective Date: Fall 2021 Scope and Sequence ● Unit 1: 2D Design: Elements and Principles of Art ● Unit 2: 2D Design: Drawing ● Unit 3: 2D Design: Painting ● Unit 4: 3D Design: Ceramics & Sculpture ● Unit 5: Media Exploration & Portfolio Development Month Unit Activities/Assessments September Unit 1: 2D Design: Elements & ● Sketchbook, Journal, Accordion Book Development MP 1 ● Color Theory Principles of Art ● Line, Value, Shape/Form, Color, Texture, Space (3-4weeks) ● Focal Point/Emphasis, Pattern, Balance, Movement/Rhythm, Unity, Contrast ● Art History & Criticism ● Building connections, relationships, and class culture October Unit 2: 2D Design: Drawing ● Sketchbook, Journal, Accordion Book Development (drawing from observation) MP1 ● Color Theory ● Line, Value, Shape/Form, Color, Texture, Space (4 weeks) ● Focal Point/Emphasis, Pattern, Balance, Movement/Rhythm, Unity, Contrast ● Art History & Criticism ● Observational Drawing (still life, portraiture) ● Drawings in a variety of media (graphite, charcoal, pen, colored pencil, etc) November Unit 2: 2D Design: Drawing ● Sketchbook, Journal, Accordion Book Development (drawing from observation) MP 2 ● Color Theory ● Line, Value, Shape/Form, Color, Texture, Space (3 weeks) ● Focal Point/Emphasis, Pattern, Balance, Movement/Rhythm, Unity, Contrast ● Art History & Criticism ● Observational Drawing ● Introduction to Painting; Watercolor Painting December Unit 3: 2D Design: Painting ● Sketchbook, Journal, Accordion Book