An Investigation Into the Effects of Chewing Gum on Consumer Endurance and Recall During an Extended Shopping Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Know Your Emeritus Member... STAN KOPECKY

Know your Emeritus Member... STAN KOPECKY Stan founded his consulting practice, which specializes in the design, development, testing and commercialization of consumer products packaging following a distinguished career with several of the largest and most sophisticated consumer products companies in the world. He began his career as a Food Research Scientist with Armour and Company. Shortly thereafter he joined Northfield, IL-based Kraft Inc. where he progressed rapidly through positions as a Packaging Research Scientist, Assistant Packaging Manager and Packaging Manager. While at Kraft, he implemented a series of programs that generated $3-5 million per year in savings in the production of rigid and flexible packaging categories; spearheaded the development of the Company’s first Vendor Certification Program for packaging materials and developed and delivered a packaging awareness program that proved successful in improving product quality and safety. Most recently Stan served as a Senior Packaging Project Manager with Chicago, IL-based Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company, the world’s largest manufacturer and marketer of chewing gum and a leader in the confectionary field. While at Wrigley, he played a major role in the evolution of the company, going from a provider of relatively indistinguishable commodities to a consumer focused, product feature driven business. In that regard, he was instrumental in achieving the number one position in the sugarless gum category by designing the packaging for Orbit tab gum, which proved to be a powerful product differentiator and which was awarded both a U.S. patent and the Company’s Creativity Award. He supported the Company’s successful entry into the breath mint segment by designing the tin and carton packaging utilized for the introduction of the Eclipse and Excel products into the U.S. -

Welcome to Your CDP Climate Change Questionnaire 2019

Mars CDP Climate Change Questionnaire 2019 31 July 2019 Welcome to your CDP Climate Change Questionnaire 2019 C0. Introduction C0.1 (C0.1) Give a general description and introduction to your organization. Mars has been proudly family owned for over 100 years. It’s this independence that gives us the gift of freedom to think in generations, not quarters, so we can invest in the long-term future of our business, our people and the planet — all guided by our enduring Principles. We believe the world we want tomorrow starts with how we do business today. Our bold ambitions must be matched with actions today from our more than 115,000 Associates in 80 countries around the world. Some of our current initiatives are: Investing $1 billion over the next several years to become sustainable in a generation Working to improve the wellbeing for families around the world Leveraging and sharing our research to create a better world for pets Every day we are one step closer to the world we want tomorrow, through our steadfast commitment to action today. Our business and the actions we take every day are founded on The Five Principles. They’re at the heart of everything we do, no matter what — making sure we don’t just talk about a better future, but work towards it every day. Through our Sustainable in a Generation Plan, we aim to grow our business in ways that are good for people, good for the planet and good for our business. The Plan sets new goals in three key areas: Healthy Planet, Thriving People and Nourishing Wellbeing. -

What's Inside

MARCH/APRIL 2018 CREATING CONNECTIONS TIDINGSNEWS & PROGRAMS IN YOUR PUBLIC LIBRARY PROGRAM Long Island Reads REGISTRATION The 2018 Long Island Reads book is: REGISTRATION BEGINS ON Spaceman: An Astronaut’s THURSDAY, MARCH 1 Unlikely Journey to Unlock In-person: the Secrets of the Universe by Mike Massimino 5:30 pm – Children 6:00 pm – Adult/Teen/Computer Online & Telephone: Book Discussion: Spaceman ISA203 7:00 pm – Adult/Teen/Computer Monday, March 26 7:00 – 8:30 pm Online: 7:00 pm – Children Join librarian Mark Irish here at the Library for a discussion of Spaceman! Both adults and teens Telephone: March 2 at 9:00 am - Children are welcome to participate in the conversation For Children’s Programs: about this inspirational true story. Refreshments Please use your children’s library card and will be provided. A copy of the book will be password, and enter all required information (age/grade). Out-of-district patrons may available for check out when you sign up at the register, space allowing, beginning March 15 Adult Reference Desk. Limited quantity – sign up except where noted. soon! Mike Massimino - Author Appearance: Sunday, April 15 For Children and Families Patchogue Theatre for the Performing Arts Come and see Mike Massimino speak at the Huga Tuga Live: Pep Rally for Reading ISJ338 Patchogue Theatre for the Performing Arts! Tickets are free and available Sunday, March 18 at https://www.eventbrite.com beginning March 1. Tickets are limited to a 1:30 – 2:30 pm quantity of 4 per order, additional tickets require an additional order. More Ages 36 months – grade 3 with caregiver information available at https://longislandreads.wordpress.com The most creative, interactive storytelling/ reading experience is right here at the Islip Library. -

Wrigley Chooses Mediaedge:Cia MEC Wins In

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wrigley chooses Mediaedge:cia MEC wins in Singapore, Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia SINGAPORE – February 8th, 2010 – Media agency Mediaedge:cia (MEC), www.mecglobal.com, announced today that following a media review they have been selected as media agency of record by Wrigley in Singapore, the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia. The appointments are effective immediately. Wrigley works with MEC in 10 countries around the world, including China and the UK. Said Stephen Li, CEO, MEC South & South East Asia “We are proud to have earned Wrigley’s business in these 4 new markets, and we look forward to leveraging our experience with the Wrigley brand in other parts of the world.” David Glass, APAC Regional Marketing Director for Wrigley said “Following a rigorous process we are delighted to announce the appointment of MEC as our media planning and buying agency in these four markets. We look forward to working together to ensure we have the best possible model consistent with our future brand and business plans. We’re convinced that MEC represents our best agency solution for the challenges ahead.” ENDS For more information, please contact: Nathalie Haxby MEC +44 20 7803 2319 [email protected] About Mediaedge:cia Mediaedge:cia (MEC) gets consumers actively engaged with our clients’ brands, leading to positive awareness, deeper relationships and stronger sales. Our services include brand and consumer insight and ROI, communications planning, media planning and buying, interaction (digital, direct, search), sport, entertainment and cause partnerships, retail consultancy and Hispanic marketing. Our 4,500 highly talented and motivated people work with local, regional and global clients from our 250 offices in 84 countries. -

04Cv346 Wrigley

Case: 1:04-cv-00346 Document #: 295 Filed: 06/26/09 Page 1 of 65 PageID #:<pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION WM. WRIGLEY JR. COMPANY, ) a Delaware corporation, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Case No.: 04-cv-0346 v. ) ) Judge Robert M. Dow, Jr. CADBURY ADAMS USA LLC, ) a Delaware limited liability company, ) ) Defendant. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Before the Court are several pending motions for summary judgment. Defendant Cadbury Adams USA LLC (“Cadbury”) moved for summary judgment pursuant to Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, seeking to establish the invalidity of Claim 34 of U.S. Patent No. 6,627,233 (the “‘233 patent”), owned by Plaintiff, Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co. (“Wrigley”), on grounds of anticipation and obviousness.1 Wrigley moved for partial summary judgment of non-infringement of U.S. Patent No. 5,009,893 (the “‘893 patent”), owned by Cadbury [209]. Cadbury then filed a cross-motion for literal infringement by Wrigley of the ‘893 Patent and for validity of the ‘893 patent [230]. The case is about cooling agents in chewing gum and mint products – specifically, Cadbury’s use of “WS-3” in its products and Wrigley’s use of “WS-23” in its products. Each party claims that the other infringed its intellectual property rights. 1 This motion was never separately entered on the docket, although it has been fully briefed and Local Rule 56.1 fact statements were submitted in support of and opposition to the motion. See [198, 206-208, 248-49]. Case: 1:04-cv-00346 Document #: 295 Filed: 06/26/09 Page 2 of 65 PageID #:<pageID> For the following reasons, Cadbury’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity is granted, Wrigley’s motion for partial summary judgment of non-infringement [209] is granted, and Cadbury’s cross-motion for literal infringement [230] is granted in part and denied in part. -

Superbrands 2006

dual benefit - teeth and consumers wants have diversified, so has Orbit's gum care in the same product range, offering additional benefits such product! as whitening, gum care and stronger teeth. Romania ranks second Despite all these, Orbit's main benefit remains worldwide in terms of cavity protection. sales of the Orbit Professional range, after the world leader, Germany. Promotion Wrigley takes an Market category, while Wrigley has simultaneously Dental Association with Free Praxis (AMSPPR). integrated approach to The Wm.Wrigley Jr. Company is the recognised created new products under these well-loved Wrigley's dental-care chewing gum brand for the the creation and delivery leader in the confectionery field and the world's brands including mints, breath strips and candies. local market is Orbit. of campaigns that make largest manufacturer and marketer of chewing Wrigley's chewing gum brands have been a good use of both gum. refreshing part of everyday life for more than History traditional and non- 100 years.The spirit In 2001, Orbit Sugarfree gum made its traditional media. of innovation that spectacular debut in the US. Already a top selling Wrigley's marketing and made Wrigley one of brand across Europe, Orbit's launch in the US promotional strategy is the world's best was a huge success. Orbit's great taste, fun designed to create known and best flavours and attractive packaging has made it a demand for its products loved companies can consumer favourite. through the use of strong still be seen today, In 2003,Wrigley diversified its product consumer advertising and with exciting new portfolio into candies with the launch of Orbit highly visible and products, new Drops, a sugar free dental candy available in recognisable in-store markets and new more than a dozen countries including Austria, display solutions. -

Wrigley's Environmental, Safety and Health (Esh)

WM. WRIGLEY JR. COMPANY 2004-2005 ENVIRONMENTAL, SAFETY AND HEALTH REPORT Dedicated to Continuous Improvement WRIGLEY’S ENVIRONMENTAL, SAFETY AND HEALTH (ESH) MISSION Be a responsive organization that integrates environmental, safety and health solutions into the business of making Wrigley products around the globe. Through leadership, innovation, knowledge sharing and effective communication, we will provide a safe workplace that encourages continuous improvement. Welcome to Wrigley’s first environmental, safety and health (ESH) performance report, which provides a snapshot of our performance for the 2004 and 2005 calendar years. This report will help you understand how ESH performance is managed at Wrigley, and how it supports our business goals. The safety performance indicators in this report begin to establish baselines for performance measurement in future-year reports. Our goal is to provide additional metrics over time as we continue to collect environmental, safety and health data and standardize our methods for doing so companywide. The metrics-related information relates to our wholly owned manufacturing facilities around the world, but this report does not cover facilities added by acquisition in 2004 and 2005. Inside This Report • Senior Management Message 3 • Integration of ESH into Wrigley Business Strategy 4 • Highlights of Wrigley’s ESH Strategic Business Plan 4 • Global ESH Policy, Organizational Structure and Standards 5 • A Commitment to Associates and Community Safety 9 • Environmental Performance 10 About Wrigley Headquartered in the historic Wrigley Building in downtown Chicago, Illinois, U.S., the Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company employs nearly 15,000 associates, and manufactures products in 24 facilities in 14 countries around the world. -

Full Line Catalog 19.Pdf

• Food Service Disposables • Paper Products • Janitorial & Chemicals c 800.234.1460 w www.rjschinner.com CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS MENOMONEE FALLS, WI “We are independent and going to stay that way!” -JIM SCHINNER, CEO Washington Maine Montana North Dakota Minnesota Vermont Oregon Wisconsin New York New Hampshire IdahoIdaho South Dakota Massachusetts Wyoming Rhode Island Michigan Connecticut IowaIowa Pennsylvania Nevada Nebraska New Jersey IllinoisIllinois Indiana Ohio Utah West Colorado Virginia Virginia Kansas Kentucky California Missouri Arizona North Carolina Tennessee Carolina Oklahoma Arkansas South New Mexico Carolina Alabama Georgia Mississippi Texas Louisiana Florida 17 Locations Nationwide! ABOUT US For over 65 years, RJ Schinner has been a leader in the wholesale distribution of From identifying opportunities, to formulating solutions, RJ Schinner is dedicated plastic and paper packaging and disposables, proudly serving the food service, to being your partner In success, helping you grow your bottom line. supermarket, and sanitation markets as a partner in success. As the largest independent distribution company in the region, our customers benefit from our enhanced flexibility, our quick to-market operation. CONTACT US With a solid track record of continued growth over the past decade, RJ Schinner NORTH Wisconsin | Minnesota | Michigan | Ohio is committed to the constant innovation required of a successful partnership. CALL 800-234-1460 Our continued investment in technology has allowed us to be an increasingly NORTHEAST Pennsylvania efficient, lean organization that is a proven contender in a very competitive CALL 855-578-7783 industry. SOUTH EAST Georgia | Tennessee | Florida | North Carolina CALL 855-578-7783 RJ Schinner has 17 distribution centers throughout the US that house over 10,000 SKU’s of domestic and internationally sourced products. -

Sweets& Snacks

Sweets & Snacks Save Friday, June 7 - Sunday, June 30, 2019 99 99 2each 7 Cadbury Wunderbar 4 pack or 99 Brown & Haley Almond Roca Mini 133g - 188g 4 each 284g McSweeney’s Jerky 99 80g - 150g 10 each Dan-D-Pak Nuts 600g/908g Tasty Treats 99 2 for 3 00 Mr. Freeze Pops 7or $3.79 each 80 x 20ml Waterbridge Allsorts, Funsorts, Wine Gums 400g, Niederegger 99 Dark Chocolate Marzipan 125g or Zazubean Chocolate 85g 2 each Twizzlers 300g - 454g 2 for 2 for 00 99 00 7or $3.79 each 99 6 each 6or $3.29 each Bounty Minis, M&M’s, 3 each Golden Bonbon Almond Nougat 250g or Russell Stover Maltesers, Mars or Twix Waterbridge Chocolate Bar 300g Toblerone Chocolate 360g No Sugar Added Chocolate 85g 165g - 230g ShipShip toto homehome Rainchecks may not be available on some lyer merchandise. ExpandedExpanded All prices are shown before applicable tax. Provincial Electronics londondrugs.comlondondrugs.com selectionselection oror pickpick upup in-storein store Recycling Environmental levy may apply on select items. J07p01_Sweets&Snacks.indd 1 05/22/19 10:19:20 AM Sweets & Snacks 2 for 00 or $2.29 each 99 4 each Ritter Sport Chocolate 100g 5 (Excludes Nut & Cacao selection) or Skinny Girl Candy 102g 99 Lindt Swiss Classic Chocolate 100g Lindt Lindor or Ghirardelli Chocolate Bag 150g - 166g 3each Snappers Chocolate 170g, Brookside Chocolates 167g - 235g, Bark Thins 150g, M&M’s Oh Canada Chocolate 190g, Lindt Classic or Grand Chocolate 150g, Whittakers Chocolate 200g Chocolate Delights 2 for 2 for 2 for 99 00 00 00 4each 6or $3.29 each 7or $3.79 each 5or $2.79 -

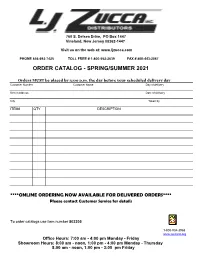

Spring/Summer 2021

760 S. Delsea Drive, PO Box 1447 Vineland, New Jersey 08362-1447 Visit us on the web at: www.ljzucca.com PHONE 856-692-7425 TOLL FREE # 1-800-552-2639 FAX # 800-443-2067 ORDER CATALOG - SPRING/SUMMER 2021 Orders MUST be placed by 3:00 p.m. the day before your scheduled delivery day Customer Number Customer Name Day of delivery Street Address Date of delivery City Taken by ITEM# QTY DESCRIPTION ****ONLINE ORDERING NOW AVAILABLE FOR DELIVERED ORDERS**** Please contact Customer Service for details X 0 A To order catalogs use item number 803205 1-800-934-3968 www.wecard.org Office Hours: 7:00 am - 4:00 pm Monday - Friday Showroom Hours: 8:00 am - noon, 1:00 pm - 4:00 pm Monday - Thursday 8:00 am - noon, 1:00 pm - 3:00 pm Friday RETURN POLICY If an item is received with LESS than the guaranteed shelf life and you believe you will not sell it before the expiration date: Contact our office within 72 hours with the invoice number, item number, quantity, and the code on the received item. The following items may be returned for credit ONLY IF PURCHASED FROM L J ZUCCA in the last 14 days and in original packaging, un-opened, and never stickered. BATTERIES GROCERIES (Case) and (Each) CANDY, GUM, MINTS FULL BOXES PAPER PRODUCTS CIGARETTE PAPERS PLAYING CARDS CIGARETTE TUBES PIPES GLOVES SPORT & TRADING CARDS Credit for the following product categories is divided into four sections FULL CREDIT RESTRICTIONS ANY "NEW" CANDY, NOVELTY, GUM, SNACK ITEM Within 60 days of our initial release CIGARS PACKS KETTLE CHIPS MEAT SNACKS NABISCO CRACKERS & COOKIES TOBACCO CREDIT WITH RESTRICTIONS RESTRICTIONS: BEVERAGE'S If received with LESS than 30 days shelf life CANDY, GUM, CRACKERS OR COOKIES If received with LESS than 30 days shelf life CANDY - HOLIDAY If returned 30 days BEFORE the Holiday CIGAR FULL BOXES Full Boxes, original packaging, un-opened, and never stickered. -

Promo Select 2018 P3

PROMO SELECT 2018 P3 LOOK INSIDE AND SEE WHAT ITEMS WE HAVE ON PROMO SELECT THIS PERIOD!! ISSUED: Apr. 30th, 2018 KEEP FOR RE-ORDERING PROMO SELECT : MAY - JUNE Hershey SAVE $0.18 A UNIT!! PRODUCT MUST BE SHIPPED BETWEEN: APRIL 30 - JULY 1, 2018 Save $4.32 a Box Description Pack Size Code # Qty Twizzler Nibs Cherry Family 24 200g 231159 Twizzler Super Nibs Cherry 24 200g 330928 Twizzler Strawberry Family 24 227g 416024 Store Name:___________________Acct #:_____________________Ship Date:_____________ ORDERS CAN BE PHONED, FAXED OR PLACED ONLINE. Winnipeg Order Desk Phone: 1.204.949.2818 Fax: 1.204.949.2828 Regina Order Desk Phone: 1.306.546.5444 Fax: 1.306.546.5555 JUST KEY – OFFICE USE ONLY ALL PROMO SELECT : MAY - JUNE Hershey SAVE $0.11 A UNIT!! PRODUCT MUST BE SHIPPED BETWEEN: APRIL 30 - JULY 1, 2018 Description Pack Size Code # Qty Save $1.76 a Box Reese Big Cup King Size 16 79g 218784 Reese Big Cup King Size w/Reese’s Pieces 16 79g 320333 Save $1.98 a Box Hershey Almond Bar King Size 18 65g 451757 Hershey Cookies N’ Creme Bar & A Half King Size 18 73g 357673 Save $2.64 a Box Eatmore King Size 24 75g 300731 Oh Henry 2 Piece King Size 24 85g 300715 Oh Henry 2 Piece Peanut Butter King Size 24 85g 161166 Reese Peanut Butter Cups King Size 24 62g 386037 Reese Sticks King Size 24 85g 246702 Store Name:___________________Acct #:_____________________Ship Date:_____________ ORDERS CAN BE PHONED, FAXED OR PLACED ONLINE. Winnipeg Order Desk Phone: 1.204.949.2818 Fax: 1.204.949.2828 Regina Order Desk Phone: 1.306.546.5444 Fax: 1.306.546.5555 JUST KEY – OFFICE USE ONLY ALL PROMO SELECT : MAY - JUNE **BOOKING ONLY** Hershey PPK HOT FEATURE PRICE!! PRODUCT MUST BE SHIPPED BETWEEN: APRIL 30 - JULY 1, 2018 SAVE $71.48 VS BUYING OPEN STOCK!! PPK CONTAINS: 48 Reese P.B. -

Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company Reports Fourth Quarter and Full-Year 2001 Financial Results Declares Dividend Increase

Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company Reports Fourth Quarter and Full-Year 2001 Financial Results Declares Dividend Increase CHICAGO – January 23, 2002 – The Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company (NYSE: WWY) announced today that earnings per share for the year ended December 31, 2001 were $1.61, up 11% over the prior year. Annual sales rose 13%, but would have increased 16% without the negative effect of foreign currency translation into a strong U.S. dollar. Fourth quarter earnings were $0.40 per share, up 14% from a year ago. Sales in the quarter were up 20% over the same period last year, due primarily to increased shipment volume, favorable product mix and selected selling price increases. Foreign currency translation did not have a material impact on sales or earnings this quarter. Bill Wrigley, Jr., President and CEO commented, “Strong sales of our core brands and the accelerated pace of new product introductions, particularly in the U.S., helped drive sales and profitability for the year. These results reflect the efforts of our entire organization and their enthusiastic implementation of our strategic business plan.” Earnings For fiscal year 2001, net earnings were up $34 million or 10% to $363 million. On a per share basis, earnings rose by $0.16 or 11% to $1.61 per share. Without the negative impact of currency translation, the full-year earnings per share gain would have been $0.19 or 13%. Fourth quarter net earnings were $90 million, up $12 million or 15%. On a per share basis, earnings for the quarter rose by $0.05 or 14% to $0.40 per share.