04Cv346 Wrigley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mars, Incorporated Donates Nearly Half a Million Dollars to Recovery

Mars, Incorporated Donates Nearly Half a Million Dollars to Recovery Efforts Following Severe Winter Storms Cash and in-kind donations will support people and pets in affected Mars communities McLEAN, Va. (February 26, 2021) — In response to the devasting winter storms across many communities in the U.S., Mars, Incorporated announced a donation of nearly $500,000 in cash and in-kind donations, inclusive of a $100,000 donation to American Red Cross Disaster Relief. Grant F. Reid, CEO of Mars said: “We’re grateful that our Mars Associates are safe following the recent destructive and dangerous storms. But, many of them, their families and friends have been impacted along with millions of others We’re thankful for partner organizations like the American Red Cross that are bringing additional resources and relief to communities, people and pets, and we’re proud to play a part in supporting that work.” Mars has more than 60,000 Associates in the U.S. and presence in 49 states. In addition to the $100,000 American Red Cross donation, Mars Wrigley, Mars Food, Mars Petcare and Royal Canin will make in-kind product donations to help people and pets. As an extension of Mars Petcare, the Pedigree Foundation is supporting impacted pets and animal welfare organizations with $25,000 in disaster relief grants. Mars Veterinary Health practices including Banfield Pet Hospital, BluePearl and VCA Animal Hospitals are providing a range of support in local communities across Texas. In addition, the Banfield Foundation and VCA Charities are donating medical supplies, funding veterinary relief teams and the transport of impacted pets. -

Retail Gourmet Chocolate

BBuullkk WWrraappppeedd Rock Candy Rock Candy Swizzle Root Beer Barrels Saltwater Taffy nndd Demitasse White Sticks Asst 6.5” 503780, 31lb bulk 577670, 15lb bulk CCaa yy 586670, 100ct 586860, 120ct (approx. 50pcs/lb) (approx. 40pcs/lb) Dryden & Palmer Dryden & Palmer Sunrise Sesame Honey Smarties Starlight, Asst Fruit Starlight Mints Starlight Spearmints Treats 504510, 40lb bulk 503770, 31lb bulk 503760, 31lb 503750, 31lb 586940, 20lb bulk (approx. 64pcs/lb) (approx. 86pcs/lb) (approx. 86pcs/lb) (approx. 80pcs/lb) (approx. 84pcs/lb) 15 tablets per roll Sunrise Sunrise Starburst Fruit Bon Bons, Strawberry Superbubble Gum Tootsie Pops, Assorted Tootsie Roll Midgee, Chews Original 503820, 31lb bulk 584010, 4lb or 530750, 39lb bulk Assorted 534672, 6/41oz (approx. 68pcs/lb) Case-8 (approx. 30pcs/lb) 530710, 30lb bulk bags (approx. 85pcs/lb) Tootsie (approx. 70pcs/lb) Tootsie Tootsie Roll Midgee Thank You Mint, Thank You Mint, Breathsavers 530700, 30lb bulk Chocolate Buttermint MM Wintergreen (approx. 70pcs/lb) 504595, 10lb bulk 504594, 10lb bulk ttss 505310, 24ct (approx. 65pcs/lb) (approx. 100pcs/lb) iinn Breathsavers Breathsavers Mentos, Mixed Fruit Altoids Smalls Altoids Smalls Peppermint Spearmint 505261, 15/1.32oz rolls Peppermint, Cinnamon, 505300, 24ct 505320, 24ct Sugar Free Sugar Free 597531, 9/.37oz 597533, 9/.37oz MM ss Altoids Altoids Altoids Altoids Smalls iinntt Wintergreen Peppermint Cinnamon Wintergreen, 597441, 12/1.76oz 597451, 12/1.75oz 597401, 12/1.76oz Sugar Free tins tins tins 597532, 9/.37oz GGuumm Stride Gum Stride -

Student Hospitalized with Meningitis More Than 80 People Seek Treatment at Student Health Services After Possible Exposure to Virus Saturday

Itt Section 2 In Sports An Associated Collegiate Press Five-Star All-American Newspaper Delaware 26 and a National Pacemaker Geared up for a Del. state 7 primus album This ain't football page 81 FREE FRIDAY Student hospitalized with meningitis More than 80 people seek treatment at Student Health Services after possible exposure to virus Saturday By Stacey Bernstein Wilmington Hospital and was throat discharges of an infected Delucia is Delaware's ninth quarters during the incubation Assistant Fratu~ Editor declared to be in intensive care as person during its incubation case of meningitis since the period. After complaining of chills, a of Wednesday night. Siebold said. period from one to 10 days, most beginning of 1993, as compared In addition, parties and other fever, a headache and a rash, a However, he said, Delucia is commonly being less than four, to two cases in 1992, Siebold social gatherings involved in university student was transferred continuing to improve each day. Siebold said. said. These cases are not related, close personal contact like sharing to Wilmington Hospital and Approximately 80 students, People who should be he said. of beverage glasses may also diagnosed with meningitis who were either at the 271 Towne concerned are those who have However, he said, it is spread the disease. Monday night, officials said. Court party or were in direct come in direct contact with the impossible to know exactly how Siebold said It is hard, Kevin Deluci'a (BE JR), who contact with Delucia, have infected individual, Siebold said. -

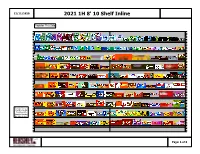

2021 1H 4' 10 Shelf Inline

12/11/2020 2021 1H 8' 10 Shelf Inline Register This Side Replace Reese's Crunchy Cookie Cup King with Reese's Crunchy Bar King in April Page: 1 of 6 12/11/2020 2021 1H 8' 10 Shelf Inline Register This Side 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Shelf: 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Shelf: 9 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Shelf: 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Shelf: 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Shelf: 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Shelf: 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Shelf: 4 Replace Reese's 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Crunchy Cookie Shelf: 3 Cup King with Reese's Crunchy Bar King in April 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Shelf: 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Shelf: 1 Page: 2 of 6 12/11/2020 2021 1H 8' 10 Shelf Inline Segment-Packtype Mints Bottle & Mega Gum Nonchocolate King and Standard Chocolate King Singles Gum Chocolate Standard Register This Side EXTRA EXTRA EXTRA ICE ICE ICE ICE ICE ICE ICE TRIDENT TRIDENT REFRESHE REFRESHE REFRESHE BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS BREAKERS VIBES S/F MENTOS MENTOS MENTOS VIBES R RS RS S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE S/F CUBE SPEARMINT PURE FRESH PURE FRESH PURE WHITE EXTRA EXTRA 5 COBALT S/F POLAR BERRY 5 RAIN PEPPERMI SPEARMIN WNTRGRN ARCTIC RASPBRY CINN BLK CHR S/F GUM - FRESH GUM - S/F GM SWT SPEARMINT 5 SPRMNT ICE MIX TRIDENT POLAR 35PC 5 RAIN 5 5 DENTYNE TROP BT SPEARMINT MNT 35PC NT T GRAPE SORBT MINT 50PC GUM SGR ICE 35PC 35PC -

Appreciation Aplenty

APPRECIATION APLENTY Giving thanks for hard-working employees, friendly coworkers, and top clients is easy and elegant with our assortment of filled-to-the-brim baskets and tins. Find our favorites — soon to be yours, too — inside. The Dazzling Gourmet Gift Basket (GNS569 $98.99) Decadent chocolates? Fresh organic fruits? Savory meats and cheeses? Whatever your gift-receiver’s fancy, find it here, paired with toasty coffee and oaky chardonnay, packed in graceful boxes and baskets, and tied with festive ribbons. Gift-giving has never been simpler, or more delicious. Visit GiftBaskets.com or call our gift-giving experts at (866) 736-2084 to order. GOLDEN STAR CHOCOLATE ELEGANCE TOWER Let our gleaming tower of cream and gold stars dazzle and delight your most valued clients and dearest family and friends. Show them your love and appreciation with this generous gift of chocolate and sweet snacks. Each star-shaped gold box holds a variety of goodies, including: Godiva dark chocolate covered pretzels, Godiva signature biscuits, Ghirardelli milk and caramel squares, white and milk chocolate enrobed sandwich cookies, roasted almonds, Godiva milk chocolate salted toffee caramels, gourmet popcorn, chocolate chip cookies, almond roca, chocolate- covered almonds, Godiva milk chocolate caramels and chocolate stars. Gift #GNS905...$99.99 PH: 866-736-2084 GHIRARDELLI CHOCOLATE DELIGHTS GIFT BASKET Assembled in a charming red gift box, this assortment of Ghirardelli chocolate favorites includes a milk and caramel chocolate bar, a gift bag of mint chocolate squares, a gift bag of dark chocolate squares, a peppermint bark chocolate bar, double chocolate hot cocoa mix, a gift bag of milk and caramel chocolate squares, and a mint cookie chocolate bar. -

Effort to Reduce Carbon Footprint | Press Releases

PRESS RELEASE Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company Launches Effort to Reduce Carbon Footprint Enabled by Infosys Technologies World’s Largest Manufacturer of Chewing Gum Seeks to Transform Logistics Operations in Western Europe London, UK - November 20, 2008: In a move to extend its social responsibility leadership, the world’s leading manufacturer of chewing gum Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company is reducing the carbon footprint it creates in its logistics operations, Infosys Technologies announced today. Infosys is enabling Wrigley to transform its logistics operations by providing solutions and services in a pilot to determine how much carbon emissions are produced and subsequently may be reduced across the company’s truck-based shipping operations in Western Europe. “Managing our impact on the environment is an integral part of Wrigley corporate philosophy,” said Ian Robertson, head of supply chain sustainability at Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company. “We’re committed to making improvements across all operations but need an integrated enterprise system to measure progress. Infosys provided that solution and services to empower that process.” Early in the pilot, Infosys identified logistics operations in which Wrigley may reduce its carbon footprint by as much as 20 percent, and provided process consulting around operational adoption. The analysis will continue to evaluate Wrigley’s complex distribution network across six countries in Western Europe – spanning more than 44 million kilometers a year in shipments between suppliers, the company and its own customers and includes its distribution centers – for CO2 emissions emitted according to the UK’s Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) standards. Infosys is using its patent-pending Logistics Optimization solution and carbon management tools to deliver the carbon footprint analysis to Wrigley as a managed information service. -

Market Achievements History Product

Wrigley ENG 15.03.2007 12:56 Page 170 Market a confectionery product.These products deliver a Since its founding in 1891,Wrigley has established range of benefits including dental protection itself as a leader in the confectionery industry. It is (Orbit), fresh breath (Winterfresh), enhancing best known for chewing gum and is the world’s memory and improving concentration (Airwaves), largest manufacturer of these products, some of relief of stress, helping in smoking cessation and which are among the best known and loved brands snack avoidance. in the world.Today,Wrigley's brands are woven into Wrigley is one of the pioneers in developing the fabric of everyday life around the world and are the dental benefits of chewing sugarfree gum - sold in over 150 countries.The original brands chewing a sugar-free gum like Orbit reduces the Wrigley’s Spearmint, Doublemint and Juicy Fruit incidence of tooth decay by 40%. Its work and have been joined by the hugely successful brands support in the area of oral healthcare has resulted Orbit,Winterfresh, Airwaves and Hubba Bubba. in dental professionals recommending sugarfree gum Chewing gum consumption in Croatia exceeds to their patients. the amount of 34 million USD and holds 34.8% of the total confectionery market (Nielsen, MAT chewing AM06). In comparison with the past year, the gum companies in the market has witnessed a 3.2% growth, and today, United States, but the industry Wrigley's Orbit is in Croatia a synonym for top was relatively undeveloped. Mr.Wrigley decided that quality chewing gum, holding the leading brand chewing gum was the product with the potential he position in the confectionery category (chocolates had been looking for, so he began marketing it excluded).This product holds 57.4% of the total under his own name. -

Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020

k Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020 For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk CONTENTS 5 USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS 5 EXPLANATION OF KASHRUT SYMBOLS 5 PROBLEMATIC E NUMBERS 6 BISCUITS 6 BREAD 7 CHOCOLATE & SWEET SPREADS 7 CONFECTIONERY 18 CRACKERS, RICE & CORN CAKES 18 CRISPS & SNACKS 20 DESSERTS 21 ENERGY & PROTEIN SNACKS 22 ENERGY DRINKS 23 FRUIT SNACKS 24 HOT CHOCOLATE & MALTED DRINKS 24 ICE CREAM CONES & WAFERS 25 ICE CREAMS, LOLLIES & SORBET 29 MILK SHAKES & MIXES 30 NUTS & SEEDS 31 PEANUT BUTTER & MARMITE 31 POPCORN 31 SNACK BARS 34 SOFT DRINKS 42 SUGAR FREE CONFECTIONERY 43 SYRUPS & TOPPINGS 43 YOGHURT DRINKS 44 YOGHURTS & DAIRY DESSERTS The information in this guide is only applicable to products made for the UK market. All details are correct at the time of going to press but are subject to change. For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk. Sign up for email alerts and updates on www.kosher.org.uk or join Facebook KLBD Kosher Direct. No assumptions should be made about the kosher status of products not listed, even if others in the range are approved or certified. It is preferable, whenever possible, to buy products made under Rabbinical supervision. WARNING: The designation ‘Parev’ does not guarantee that a product is suitable for those with dairy or lactose intolerance. WARNING: The ‘Nut Free’ symbol is displayed next to a product based on information from manufacturers. The KLBD takes no responsibility for this designation. You are advised to check the allergen information on each product. k GUESS WHAT'S IN YOUR FOOD k USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS Hi Noshers! PRODUCTS WHICH ARE KLBD CERTIFIED Even in these difficult times, and perhaps now more than ever, Like many kashrut authorities around the world, the KLBD uses the American we need our Nosh! kosher logo system. -

Members' Magazine

MEMBERS’ MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2018 Supporting the Human-Animal Bond Alberta Helping Animals Society 2018 VETERINARY PRESENTED BY FORENSICS WORKSHOP From routine investigations to cases that end up in court, veterinary forensics is an emerging area of study in the veterinary profession. Put your skills to the test at this two day workshop featuring: • Veterinary Forensics 101: Investigations, • Panel presentation with ABVMA, Animal Evidence Collection, Forensic Reports, Care and Control (ACC) Edmonton, Alberta Toxicology, Pathology Agriculture and Forestry, (AAF) Calgary Dr. Margaret Doyle, Riverbend Veterinary Humane Society (CHS), Alberta SPCA (ABSPCA) Clinic, and Mr. Brad Nichols, Calgary Dr. Phil Buote - (ABVMA), Mr. Keith Scott Humane Society (ACC), Dr. Hussein Keshwani (AAF), Mr. Brad • Issues with Recongition and Reporting: Nichols (CHS), Mr. Ken Dean (ABSPCA) Six Stages of Veterinary Response to • Solve the Case, dinner and networking event - Animal Cruelty, Abuse and Neglect submit your case slides for an open discussion Dr. Phil Arkow, The National Link Coalition of various forensics cases • The Animal Abuse/Family Violence Link and • Preparing for Court Its Implications for Veterinary Social Work Ms. Rose Greenwood, Crown Prosecutor, Dr. Phil Arkow, The National Link Coalition Justice and Solicitor General • Emotional Suffering of Animals or People in • Necropsy, handling the post-mortem Animal Abuse Cases Dr. Nick Nation, Animal Pathology Services Ltd. Dr. Rebecca Ledger, Animal Behaviour and • Compiling the Case for Trial Welfare Scientist, Langara College Crime Scene Photography • The Animal Protection Act in Alberta Constable Stuart Saunders, Edmonton - it’s impact on various organizations. Police Service Role of Vet and Tech Teams in the Field Mr. -

Wrigley Some Research Online to Help

The 7 Steps - April 1. CONTEXT Mindmap anything you know about the topic, including vocabulary. Do Wrigley some research online to help. Listening Questions 1 1. In what year was Wrigley founded? 2. QUESTIONS . 2. What was the first product William Wrigley Jr. sold? . Read the listening questions to 3. Why did he decide to focus on selling gum? check your . understanding. 4. When was the Doublemint flavor introduced? Look up any new vocabulary. 5. Who bought Wrigley in 2008? . 3. LISTEN Listening Questions 2 1. Which MLB team did the Wrigley family own and when did they sell it? Listen and answer . the questions 2. How old is Fenway Park? using full sentences. Circle . the number of times and % you 3. What does Koshien Stadium share in common with Wrigley Field? understood. 4. When was the first official night game played at Wrigley Field? . 5. How long did the Chicago Cubs go between World Series championships? Listening 1 1 2 3 4 5 . % % % % % Discussion Questions 1. What snacks did you eat when you were younger? Is gum a popular snack in Japan? Listening 2 1 2 3 4 5 2. How do you feel about huge companies investing in sporting teams? How does it benefit them? % % % % % 4. CHECK ANSWERS TRANSCRIPT 1 When it comes to chewing gum, the Wrigley name is one of the most famous. The Wm. Wrigley Read through the Jr. Company, or Wrigley for short, was founded by William Wrigley Jr. in 1891 and is transcript and headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. underline the When William Wrigley Jr. -

New Products and Promotions

Fusion Gourmet USA NEW PRODUCTS Dolcetto Wafer Rolls, made from all natural ingredients, AND PROMOTIONS are light and crispy on the out- side with a creamy filling. Fla- vors include Tiramisu, Choco- late and Cappuccino. They come packaged in a 14.1 oz vintage-style tin and are available in shippers. Tel: +1 (310) 532 8938 www.fusiongourmet.com Impact Confections, Inc. USA Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co. USA Warheads Double Drops is a supersour candy liq- uid with two flavors in a two-chamber, dual- dropper bottle. Enjoy one flavor at a time or both. Flavor combos include green apple/ watermelon, blue raspberry/green apple and watermelon/blue raspberry. Available in a Orbit White Wintermint is a new fla- 24-count display with an srp of 99¢. vor of the teeth-whitening, stain- Warheads Juniors removing Orbit gum. Extreme Sour hard Eclipse Cinnamon Inferno and candy is a miniature Midnight Cool are two new fla- version of the original Extreme vors of Eclipse breath-freshening Sour candy in a sleek dis- gum. penser, with an assortment of five Altoids Mango Sours are a new sour flavors for mix-and-match flavor sensation and control fruit flavor Altoids hard candy. of sour intensity. Flavors include apple, black cherry, Extra Cool Watermelon is a blue raspberry, lemon and watermelon. Ships in an 18- new flavor addition to Extra count display with an srp of 99¢. gum. Tel: +1 (719) 268 6100 www.impactconfections.com Doublemint Twins Mints, an extension of the Dou- Van Damme Confectionery, Inc. USA blemint brand, come Van Damme has introduced All in two flavors, Winter- Natural Marshmallow Cubes, a mix creme and Mintcreme. -

Know Your Emeritus Member... STAN KOPECKY

Know your Emeritus Member... STAN KOPECKY Stan founded his consulting practice, which specializes in the design, development, testing and commercialization of consumer products packaging following a distinguished career with several of the largest and most sophisticated consumer products companies in the world. He began his career as a Food Research Scientist with Armour and Company. Shortly thereafter he joined Northfield, IL-based Kraft Inc. where he progressed rapidly through positions as a Packaging Research Scientist, Assistant Packaging Manager and Packaging Manager. While at Kraft, he implemented a series of programs that generated $3-5 million per year in savings in the production of rigid and flexible packaging categories; spearheaded the development of the Company’s first Vendor Certification Program for packaging materials and developed and delivered a packaging awareness program that proved successful in improving product quality and safety. Most recently Stan served as a Senior Packaging Project Manager with Chicago, IL-based Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company, the world’s largest manufacturer and marketer of chewing gum and a leader in the confectionary field. While at Wrigley, he played a major role in the evolution of the company, going from a provider of relatively indistinguishable commodities to a consumer focused, product feature driven business. In that regard, he was instrumental in achieving the number one position in the sugarless gum category by designing the packaging for Orbit tab gum, which proved to be a powerful product differentiator and which was awarded both a U.S. patent and the Company’s Creativity Award. He supported the Company’s successful entry into the breath mint segment by designing the tin and carton packaging utilized for the introduction of the Eclipse and Excel products into the U.S.