Churchman 128 3.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHURCHOF ENGLAND Newspaper

THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER. ESTABLISHED IN 1828 Celebrating Metropolitan THE Anthony P10 CHURCHOF ENGLAND Newspaper NOW AVAILABLE ON NEWSSTAND Standing together with FRIDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2014 No: 6250 the persecuted, p11 Traditionalist group reaffirms its commitment to the biblical stance on marriage Reform rethinking planned boycott THE ANGLICAN evangelical In addition, Reform claimed, the shared conversations in the ‘shared disagreement’ on the can respond pastorally to indi- group, Reform, is revising their that the objectives would also Church of England on Sexuality, issue of same-sex relationships, vidual needs. But the scripture’s commitment to the shared con- require participants: “To accept Scripture and Mission states and accepting that there is teachings on sexuality are not versations in the Church of Eng- an outcome in which the that one of the two main objec- every possibility of a shared an abstract concept we’ve land on Sexuality, Scripture and Church moves from its present, tives of the shared conversation conversation being set up, invented. Mission. biblical, understanding of mar- is “clarifying how we (CofE) can whilst conceding to terms of ref- “We are worried that the mes- Reform released a statement riage to one where we accom- most effectively be a missionary erence with predetermined out- sage being sent out in individual arguing that a second revision modate two separate beliefs, church in a changing culture comes. parishes across the UK is that of the objectives of the shared with one part of the Church call- around sexuality” and the other Mr Thomas said: “We accept we can affirm the faith, whilst conversation following the Col- ing for repentance over sexual is “to clarify the implications of the authority of the scripture disagreeing on sexuality,” he lege of Bishops meeting in Sep- sin and another declaring God’s what it means for the Church of and we are looking for ways we told us. -

Th E Year in Review

2012 – 2013 T HE Y EAR IN R EVIEW C AMBRIDGE T HEOLOGICAL F EDERATION Contents Page Foreword from the Bishop of Ely 3 Principal’s Welcome 4 Highlights of the Year 7 The Year in Pictures 7 Cambridge Theological Federation 40th anniversary 8 Mission, Placements and Exchanges: 10 • Easter Mission 10 USA Exchanges 11 • Yale Divinity School 11 • Sewanee: The University of the South 15 • Hong Kong 16 • Cape Town 17 • Wittenberg Exchange 19 • India 20 • Little Gidding 21 Prayer Groups 22 Theological Conversations 24 From Westcott to Williams: Sacramental Socialism and the Renewal of Anglican Social Thought 24 Living and Learning in the Federation 27 Chaplaincy 29 • ‘Ministry where people are’: a view of chaplaincy 29 A day in the life... • Bill Cave 32 • Simon Davies 33 • Stuart Hallam 34 • Jennie Hogan 35 • Ben Rhodes 36 New Developments 38 Westcott Foundation Programme of Events 2013-2014 38 Obituaries and Appreciations 40 Remembering Westcott House 48 Ember List 2013 49 Staff contacts 50 Members of the Governing Council 2012 – 2013 51 Editor Heather Kilpatrick, Communications Officer 2012 – 2013 THE YEAR IN REVIEW Foreword from the Bishop of Ely It is a great privilege to have become the Chair of the Council of“ Westcott House. As a former student myself, I am conscious just how much the House has changed through the years to meet the changing demands of ministry and mission in the Church of England, elsewhere in the Anglican Communion and in the developing ecumenical partnerships which the Federation embodies. We have been at the forefront in the deliberations which have led to the introduction of the Common Awards. -

Download 1 File

GHT tie 17, United States Code) r reproductions of copyrighted Ttain conditions. In addition, the works by means of various ents, and proclamations. iw, libraries and archives are reproduction. One of these 3r reproduction is not to be "used :holarship, or research." If a user opy or reproduction for purposes able for copyright infringement. to accept a copying order if, in its involve violation of copyright law. CTbc Minivers U^ of Cbicatjo Hibrcmes LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM LONDON Cambridge University Press FETTER LANE NEW YORK TORONTO BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS Macmillan TOKYO Maruzen Company Ltd All rights reserved Phot. Russell BISHOP LIGHTFOOT IN 1879 LIGHTFOOT OF DURHAM Memories and Appreciations Collected and Edited by GEORGE R. D.D. EDEN,M Fellow Pembroke Honorary of College, Cambridge formerly Bishop of Wakefield and F. C. MACDONALD, M.A., O.B.E. Honorary Canon of Durham Cathedral Rector of Ptirleigb CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1933 First edition, September 1932 Reprinted December 1932 February PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN 1037999 IN PIAM MEMORIAM PATRIS IN DEO HONORATISSIMI AMANTISSIMI DESIDERATISSIMI SCHEDULAS HAS QUALESCUNQUE ANNOS POST QUADRAGINTA FILII QUOS VOCITABAT DOMUS SUAE IMPAR TRIBUTUM DD BISHOP LIGHTFOOT S BOOKPLATE This shews the Bishop's own coat of arms impaled^ with those of the See, and the Mitre set in a Coronet, indicating the Palatinate dignity of Durham. Though the Bookplate is not the Episcopal seal its shape recalls the following extract from Fuller's Church 5 : ense History (iv. 103) 'Dunelmia sola, judicat et stola. "The Bishop whereof was a Palatine, or Secular Prince, and his seal in form resembleth Royalty in the roundness thereof and is not oval, the badge of plain Episcopacy." CONTENTS . -

A Report of the House of Bishops' Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church Ho

Women Bishops in the Church of England? A report of the House of Bishops’ Working Party on Women in the Episcopate Church House Publishing Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3NZ Tel: 020 7898 1451 Fax: 020 7989 1449 ISBN 0 7151 4037 X GS 1557 Printed in England by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Published 2004 for the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England by Church House Publishing. Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2004 Index copyright © Meg Davies 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored or transmitted by any means or in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without written permission, which should be sought from the Copyright Administrator, The Archbishops’ Council, Church of England, Church House, Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3NZ. Email: [email protected]. The Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, and are used by permission. All rights reserved. Contents Membership of the Working Party vii Prefaceix Foreword by the Chair of the Working Party xi 1. Introduction 1 2. Episcopacy in the Church of England 8 3. How should we approach the issue of whether women 66 should be ordained as bishops? 4. The development of women’s ministry 114 in the Church of England 5. Can it be right in principle for women to be consecrated as 136 bishops in the Church of England? 6. -

Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an Historical and Theological Examination of the Role of Ecclesiology in the Church of England Since the Second World War

Durham E-Theses Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the church of England since the second world war Bagshaw, Paul How to cite: Bagshaw, Paul (2000) Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the church of England since the second world war, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4258/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Ecclesiology in the Church of England: an historical and theological examination of the role of ecclesiology in the Church of England since the Second World War The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should i)C published in any form, including; Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent. -

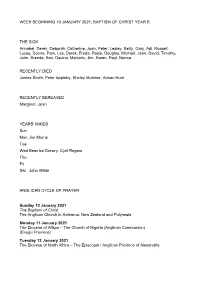

Week Beginning 10 January 2021; Baptism of Christ Year B

WEEK BEGINNING 10 JANUARY 2021; BAPTISM OF CHRIST YEAR B THE SICK Annabel, Derek, Deborah, Catherine, Joan, Peter, Lesley, Betty, Gary, Adi, Russell, Lucas, Donna, Pam, Les, Derek, Freda, Rosie, Douglas, Michael, Jean, David, Timothy, John, Brenda, Ken, Davina, Malcolm, Jim, Karen, Paul, Norma RECENTLY DIED James Smith, Peter Appleby, Shirley Mutimer, Adrian Hunt RECENTLY BEREAVED Margaret, Jean YEARS’ MINDS Sun Mon Jim Morris Tue Wed Beatrice Drewry, Cyril Rogers Thu Fri Sat John White ANGLICAN CYCLE OF PRAYER Sunday 10 January 2021 The Baptism of Christ The Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia Monday 11 January 2021 The Diocese of Afikpo – The Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion) (Enugu Province) Tuesday 12 January 2021 The Diocese of North Africa – The Episcopal / Anglican Province of Alexandria Wednesday 13 January 2021 The Diocese of the Horn of Africa – The Episcopal / Anglican Province of Alexandria Thursday 14 January 2021 The Diocese of Agra – The (united) Church of North India Friday 15 January 2021 The Diocese of Aguata – The Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion) (Niger Province) Saturday 16 January 2021 The Diocese of Ahoada – The Church of Nigeria (Anglican Communion) (Niger Delta Province) Information regarding Coronavirus from the Church of England including helpful prayer and liturgical resources can be accessed at: https://bit.ly/33PHxMZ LICHFIELD DIOCESE PRAYER DIARY – DISCIPLESHIP, VOCATION, EVANGELISM Sunday 10thJanuary: (William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1645) For our Diocesan Bishop, Rt Revd Dr Michael Ipgrave; for members of the Bishop’s Staff team including Rt Revd Clive Gregory, Area Bishop of Wolverhampton; the Ven Matthew Parker, Area Bishop of Stafford (elect); Rt Revd Sarah Bullock, Area Bishop of Shrewsbury and all Archdeacons; for Canon Julie Jones, Chief Executive Officer and Diocesan Secretary as she heads the administrative team and implementation of Diocesan strategy; for the Very Revd Adrian Dorber, Dean of Lichfield and head of Lichfield Cathedral and Revd Dr Rebecca Lloyd, Bishop's Chaplain. -

The Lichfield Diocesan Board of Finance (Incorporated)

Registered number: 00239561 Charity number: 1107827 The Lichfield Diocesan Board of Finance (Incorporated) Annual Report and Financial Statements For the year ended 31 December 2015 The Lichfield Diocesan Board of Finance (Incorporated) (A company limited by guarantee) Contents Page Reference and administrative details of the charity, its trustees and advisers 1 - 2 Chairman's statement 3 Trustees' report 4 - 20 Independent auditors' report 21 - 22 Consolidated statement of financial activities 23 Consolidated income and expenditure account 24 Consolidated balance sheet 25 Company balance sheet 26 Consolidated cash flow statement 27 Notes to the financial statements 28 - 61 The Lichfield Diocesan Board of Finance (Incorporated) (A company limited by guarantee) Reference and Administrative Details of the Company, its Trustees and Advisers For the year ended 31 December 2015 President The Bishop of Lichfield, (Vacant from 1 October 2015) Chair Mr J T Naylor Vice Chair The Archdeacon of Stoke upon Trent Ex-Officio The Bishop of Shrewsbury The Bishop of Stafford The Bishop of Wolverhampton The Dean of Lichfield The Archdeacon of Lichfield The Archdeacon of Salop The Archdeacon of Stoke upon Trent The Archdeacon of Walsall (appointed 1 January 2015) The Revd Preb J Allan RD Mr J Wilson Dr A Primrose Elected The Revd P Cansdale The Revd J Cody (appointed 1 February 2016) The Revd Preb P Daniel (resigned 31 August 2015) The Revd M Kinder (resigned 31 August 2015) The Revd M Last (appointed 1 September 2015) The Revd B Leathers (resigned 31 August -

That This Synod Ask the Ho

1. In July 2000, General Synod passed the following motion proposed by the Archdeacon of Tonbridge: That this Synod ask the House of Bishops to initiate further theological study on the episcopate, focussing on the issues that need to be addressed in preparation for the debate on women in the episcopate in the Church of England, and to make a progress report on this study to Synod in the next two years. 2. In order to carry out the theological study referred to in Archdeacon Judith Rose’s motion, the House of Bishops established a working party which began its work in April 2001. The membership of the working party is as follows: The Rt Revd Dr Michael Nazir-Ali (Bishop of Rochester, Chairman) Dr Christina Baxter (Principal, St John’s College, Nottingham) The Rt Revd Wallace Benn (Bishop of Lewes) The Very Revd Vivienne Faull (Provost of Leicester) The Rt Revd David Gillett (Bishop of Bolton) The Revd Deacon Christine Hall (University College, Chichester) The Rt Revd Christopher Herbert (Bishop of St Albans) The Rt Revd Christopher Hill (Bishop of Stafford) Professor Ann Loades (University of Durham) The Rt Revd Dr Geoffrey Rowell (Bishop of Gibraltar in Europe) The Ven Dr Joy Tetley (Archdeacon of Worcester) 1 In addition there are two ecumenical representatives: The Revd Dr Anthony Barratt (Vice Rector, St John’s Seminary, Wonersh - The Roman Catholic Church) The Revd Dr Richard Clutterbuck (Principal, The West of England Ministerial Training Course - The Methodist Church) two consultants: The Revd Prof Nicholas Sagovsky (University of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne) The Revd Canon Professor Anthony Thiselton (University of Nottingham) and three staff assessors: The Revd Preb Dr Paul Avis (General Secretary, CCU) Mr Philip Mawer (Secretary General, House of Bishops) Mr Stephen Slack (Legal Officer, Archbishops Council) In attendance: Dr Martin Davie (Theological Consultant, House of Bishops, Secretary to the Working Party) Mr Jonathan Neil-Smith (Secretary, House of Bishops) Mr Adrian Vincent (Executive Officer, House of Bishops). -

Eagle March April 2018

St. John’s Burns Night Supper, Saturday 27th January 2018 Photograph by Michael St. John’s Burns Night Supper, Saturday 27th January 2018 Photograph by Kirsteen 2 From the Rectory It is indeed my great pleasure to meet you through 'the Eagle'! A little over a month has passed since I was licensed and installed as Priest in Charge at St John's and I am encouraged that it's been a good first month! I was ordained in the Church of South India and have been involved in the ministry of the church in various ca- pacities in India and in the UK over the past twenty years. My wife, Grace, is also an ordained minister and we are blessed with three children: Felina, Erina and Darshan, who are settling well in their schools and nursery. My doctoral studies at the University of Nottingham brought us to the UK in 2011 and seven years on, I am delighted to have received the call to serve as Priest at St John's Forres. It's a privilege and joy to join in the long-standing and continuing Christian witness and heritage of this place. We are grateful for the warmth, welcome and goodwill extended to us. Evidently, a lot of work has gone into preparations, particularly the redec- oration of the Rectory and the work in the gardens. With the unpacking now completed, we are delighted to have this beautiful house as our home. We are enjoying getting acquainted with the beautiful surround- ings and friendly people of Forres. We look forward to getting to know you all and participate in the vibrant community spirit obvious both in the church and in the town. -

DISPENSATION and ECONOMY in the Law Governing the Church Of

DISPENSATION AND ECONOMY in the law governing the Church of England William Adam Dissertation submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Wales Cardiff Law School 2009 UMI Number: U585252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585252 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..................................................................................................................................VI ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................................................................................VII TABLE OF STATUTES AND MEASURES............................................................................................ VIII U K A c t s o f P a r l i a m e n -

English Spirituality: a Review Article by Jerry R. Flora Gordon Mursell

Ashland Theological Journal 2006 English Spirituality: A Review Article By Jerry R. Flora Gordon Mursell, English Spirituality. 200l. 2 vols. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. 548, 580 pp. $39.95 ea. Imposing. Impressive. Intimidating. Such feelings must be normal when one first approaches Gordon Mursell' s history of Christian spirituality in England. In bulk the two blue volumes resemble the black tomes of Karl Barth's Church Dogmatics. With 1128 pages and more than 6000 fine-print notes, this is a work to be reckoned with. But it is also interesting and inviting. Mursell's clear style and pastoral approach make it a journey worth taking as he surveys almost two millennia of faith. The massive documentation reveals that the author has read widely, deeply, and carefully. This is no quick overview, but a refined, nuanced discussion abounding in detail. From Regent College in Vancouver, veteran teacher and author James Houston writes, "This is the most comprehensive, scholarly, and up-to-date survey ... an essential guide and standard history of the subject" (dust jacket). Not yet sixty years of age, the Very Reverend Gordon Mursell is Area Bishop of Stafford in the Diocese of Lichfield. Born in Surrey, he initially studied at the Pontifical Institute of Sacred Music in Rome. While there he lived with a family whose genuine faith caused him to begin taking Christianity seriously. Returning to England, he joined the Anglican Church, attended Oxford University's Brasenose College, and trained for ordination. Since then he has been a parish priest, an instructor in pastoral studies and spirituality, and provost and dean of Birmingham Cathedral. -

Lancelot Andrewes' Life And

LANCELOT ANDREWES’ LIFE AND MINISTRY A FOUNDATION FOR TRADITIONAL ANGLICAN PRIESTS by Orville Michael Cawthon, Sr. B.B.A, Georgia State University, 1983 A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religion at Reformed Theological Seminary Charlotte, North Carolina September 2014 Accepted: Thesis Advisor ______________________________ Donald Fortson, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT Lancelot Andrewes Life and Ministry A Foundation for Traditional Anglican Priest Orville Michael Cawthon, Sr. This thesis explores Lancelot Andrewes’ life and ministry as an example for Traditional Anglican Priests. An introduction and biography are presented, followed by an examination of his prayer life, doctrine, and liturgy. His prayer life is examined through his private prayers, via tract number 88 of the Tracts for the Times, daily prayers, and sermons. The second evaluation made is of Andrewes’ doctrine. A review of his catechism is followed by his teaching of the Commandments. His sermons are examined and demonstrate his desire and ability to link the Old Testament and the New Testament through Jesus Christ and a review is made through examining his sermons for the different church seasons. Thirdly, Andrewes’ liturgy is the focus, as many of his practices are still used today within the Traditional Anglican Church. His desire for holiness and beauty as reflected in his Liturgy is seen, as well as his position on what should be allowed in the worship of God. His love for the Eucharist is examined as he defends the English Church’s use of the term “Real Presence” in its relationship to the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist.