INFORMATION to USERS the Quality of This Reproduction Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUPREME COURT of INDIA Page 1 of 4 PETITIONER: CHANDRAKANTA GOYAL

http://JUDIS.NIC.IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 1 of 4 PETITIONER: CHANDRAKANTA GOYAL Vs. RESPONDENT: SOHAN SINGH JODH SINGH KOHLI DATE OF JUDGMENT11/12/1995 BENCH: VERMA, JAGDISH SARAN (J) BENCH: VERMA, JAGDISH SARAN (J) SINGH N.P. (J) VENKATASWAMI K. (J) CITATION: 1996 AIR 861 1996 SCC (1) 378 JT 1995 (9) 114 1995 SCALE (7)88 ACT: HEADNOTE: JUDGMENT: J U D G M E N T J.S. VERMA, J.: This is an appeal under Section 116A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (for short "the Act") by the returned candidate against the judgment dated 1st & 2nd July, 1991 of H. Suresh, J. of the Bombay High Court in Election Petition No. 19 of 1990 by which the election of the appellant has been set aside on the ground under Section 100(1)(b) for commission of corrupt practices under sub- sections (3) and (3A) of Section 123 of the Act. The appellant was candidate of the Bhartiya Janata Party and respondent was the candidate of the Janata Dal for election to the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly from No. 33, Matunga Constituency held on 27.2.1990. The appellant became candidate at the election on 8.2.1990. The date of poll was 27.2.1990 and the election result was declared on 1.3.1990 at which the appellant was declared duly elected having secured 31,530 votes while the respondent (election petitioner) had secured 28,021 votes and the Congress candidate secured 28,426 votes. The election petition was filed on the ground under Section 100(1)(b) alleging commission of corrupt practices under Sections 123(3) and 123(3A) of the Act. -

Download Brochure

Celebrating UNESCO Chair for 17 Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance Years of Academic Excellence World Peace Centre (Alandi) Pune, India India's First School to Create Future Polical Leaders ELECTORAL Politics to FUNCTIONAL Politics We Make Common Man, Panchayat to Parliament 'a Leader' ! Political Leadership begins here... -Rahul V. Karad Your Pathway to a Great Career in Politics ! Two-Year MASTER'S PROGRAM IN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNMENT MPG Batch-17 (2021-23) UGC Approved Under The Aegis of mitsog.org I mitwpu.edu.in Seed Thought MIT School of Government (MIT-SOG) is dedicated to impart leadership training to the youth of India, desirous of making a CONTENTS career in politics and government. The School has the clear § Message by President, MIT World Peace University . 2 objective of creating a pool of ethical, spirited, committed and § Message by Principal Advisor and Chairman, Academic Advisory Board . 3 trained political leadership for the country by taking the § A Humble Tribute to 1st Chairman & Mentor, MIT-SOG . 4 aspirants through a program designed methodically. This § Message by Initiator . 5 exposes them to various governmental, political, social and § Messages by Vice-Chancellor and Advisor, MIT-WPU . 6 democratic processes, and infuses in them a sense of national § Messages by Academic Advisor and Associate Director, MIT-SOG . 7 pride, democratic values and leadership qualities. § Members of Academic Advisory Board MIT-SOG . 8 § Political Opportunities for Youth (Political Leadership diagram). 9 Rahul V. Karad § About MIT World Peace University . 10 Initiator, MIT-SOG § About MIT School of Government. 11 § Ladder of Leadership in Democracy . 13 § Why MIT School of Government. -

Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Candidate List.Xlsx

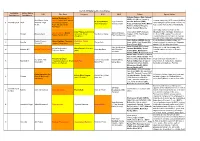

List of All Maharashtra Candidates Lok Sabha Vidhan Sabha BJP Shiv Sena Congress NCP MNS Others Special Notes Constituency Constituency Vishram Padam, (Raju Jaiswal) Aaditya Thackeray (Sunil (BSP), Adv. Mitesh Varshney, Sunil Rane, Smita Shinde, Sachin Ahir, Ashish Coastal road (kolis), BDD chawls (MHADA Dr. Suresh Mane Vijay Kudtarkar, Gautam Gaikwad (VBA), 1 Mumbai South Worli Ambekar, Arjun Chemburkar, Kishori rules changed to allow forced eviction), No (Kiran Pawaskar) Sanjay Jamdar Prateep Hawaldar (PJP), Milind Meghe Pednekar, Snehalata ICU nearby, Markets for selling products. Kamble (National Peoples Ambekar) Party), Santosh Bansode Sewri Jetty construction as it is in a Uday Phanasekar (Manoj Vijay Jadhav (BSP), Narayan dicapitated state, Shortage of doctors at Ajay Choudhary (Dagdu Santosh Nalaode, 2 Shivadi Shalaka Salvi Jamsutkar, Smita Nandkumar Katkar Ghagare (CPI), Chandrakant the Sewri GTB hospital, Protection of Sakpal, Sachin Ahir) Bala Nandgaonkar Choudhari) Desai (CPI) coastal habitat and flamingo's in the area, Mumbai Trans Harbor Link construction. Waris Pathan (AIMIM), Geeta Illegal buildings, building collapses in Madhu Chavan, Yamini Jadhav (Yashwant Madhukar Chavan 3 Byculla Sanjay Naik Gawli (ABS), Rais Shaikh (SP), chawls, protests by residents of Nagpada Shaina NC Jadhav, Sachin Ahir) (Anna) Pravin Pawar (BSP) against BMC building demolitions Abhat Kathale (NYP), Arjun Adv. Archit Jaykar, Swing vote, residents unhappy with Arvind Dudhwadkar, Heera Devasi (Susieben Jadhav (BHAMPA), Vishal 4 Malabar Hill Mangal -

1. Councillors & Officers List

Yeejleer³e je<ì^ieerle HetCe& peveieCeceve-DeefOevee³ekeÀ pe³e ns Yeejle-Yeei³eefJeOeelee ~ Hebpeeye, efmebOeg, iegpejele, cejeþe, NATIONAL ANTHEM OF INDIA êeefJe[, GlkeÀue, yebie, efJebO³e, efncee®eue, ³ecegvee, iebiee, Full Version G®íue peueeqOelejbie leJe MegYe veeces peeies, leJe MegYe DeeeqMe<e ceeies, Jana-gana-mana-adhinayaka jaya he ieens leJe pe³eieeLee, Bharat-bhagya-vidhata peveieCe cebieueoe³ekeÀ pe³e ns, Punjab-Sindhu-Gujarata-Maratha Yeejle-Yeei³eefJeOeelee ~ Dravida-Utkala-Banga pe³e ns, pe³e ns, pe³e ns, pe³e pe³e pe³e, pe³e ns ~~ Vindhya-Himachala-Yamuna-Ganga mebef#eHle Uchchala-jaladhi-taranga peveieCeceve-DeefOevee³ekeÀ pe³e ns Tava Shubha name jage, tava subha asisa mage Yeejle-Yeei³eefJeOeelee ~ Gahe tava jaya-gatha pe³e ns, pe³e ns, pe³e ns, Jana-gana-mangala-dayaka jaya he pe³e pe³e pe³e, pe³e ns ~~ Bharat-bhagya-vidhata Jaya he, jaya he, jaya he, Jaya jaya jaya jaya he. Short version Jana-gana-mana-adhinayaka jaya he Bharat-bhagya-vidhata Jaya he, Jaya he, jaya he jaya jaya jaya, jaya he, PERSONAL MEMORANDUM Name ............................................................................................................................................................................ Office Address .................................................................................................................... ................................................................................................................................................ .................................................... .............................................................................................. -

PMC Architect List

Name Mobile Number E-mail Address a BERI +919422416884 , a CHAUDHRI 26363841 , A chavan 962345513 [email protected] pune , a chimbalkar 9422401434 pushkraj 31 mukand nager , pune 37 a Chimbalkar 9422401434 , a DANDEKAR +919823084532 , a gaikwad 9822475765 s.n. 127a agtechpa rkgaikeaven , e aundh pune a KOKATE +9198906609018 , a KULKARNI +919822867377 , A KULKARNI +919822867377 , a MANGOKAR , A Muralidharan 9868943699 civil construction wing , all india radio,schoona bhawan a PARDESHI 9822621231 , a PUNGONKAR , A SHETH 250233623 , a SUTAR , A P MAHADKAR , A. B. SIRDESAI A. B. VAIDYA 9890047993 [email protected] 4,dattaprasad,1206B/7 , jm road A. G. BHADE A. J. HATKAR A. N. FATEH A. P. MAHDKAR A. R. JOSHI A. S. THOMBARE +919822027452 , A. V. GAWADE Registration No CA\77\4270 CA\94\17004 abc ca/75/708 CA/75/708 CA\97\21869 ca/2005/36683 CA/04/33802 CA/85/09380 CA\85\9380 CA\ \5298 CA/89/12033 CA\86\10340 CA\76\2678 CA/2004/33112 CA\83\7717 CA\83\7830 CA\83\ CA\81\6581 CA\00\54135 CA\77\3607 CA\86\9741 CA\ \7830 CA\75\698 CA/86/10352 CA\84\8081 Name Mobile Number E-mail Address A. V. PATIL A. W. LIMYE AARTI JAYANT JOSHI +919423305778 AASIA MEHMOOD SHAIKH 9850030183 aasia [email protected] 77 WANNORIE TWIN TOWER , BUNGLOW PUNE ABHAY ANIL PAWAR 9881120459 [email protected] 4, Sulkshana Heights, 120/11, Modern Colony, , Paud Road, Kothrud ABHAY B. SHARMA ABHAY BAPUJI DESAI ABHAY M TONDANKAR ABHAY PRADEEP BHOSALE 9422001474 rajshree.associates2k@gmail. 9/B,GIRIDARSHAN SOC., , BANER RD., AUNDH, PUNE com 07. -

Uddhav Sworn in As CM of New 'Secular Govt' in Maha

c m y k c m y k THE LARGEST CIRCULATED ENGLISH DAILY IN SOUTH INDIA HYDERABAD I FRIDAY I 29 NOVEMBER 2019 deccanchronicle.com, facebook.com/deccannews, twitter.com/deccanchronicle, google.com/+deccanchronicle Vol. 82 No. 329 Established 1938 | 40 PAGES | `6.00 Godse praise KCR lets RTC proves costly Uddhav sworn in as CM of for Pragya staff join duty DC CORRESPONDENT NEW DELHI, NOV. 28 new ‘secular govt’ in Maha Hikes fare by 20paise per km Left red-faced after its Bhopal S.A. ISHAQUI | DC MP and Malegaon blasts BHAGWAN PARAB | DC HYDERABAD, NOV. 28 accused Pragya Singh MUMBAI, NOV. 28 LIST OF MINISTERS MAHA ALLIANCE Thakur’s praise for Mahatma Giving relief to TSRTC Gandhi’s assassin Nathuram Shiv Sena chief Uddhav WHO TOOK OATH TO WAIVE OFF workers, who have ended Godse as a patriot, the BJP on Thackeray was on Friday ◗ Uddhav Thackeray their 55-day-old strike and Thursday barred her from sworn in as the chief min- Chief minister are waiting to return to attending its parliamentary ister of Maharashtra amid ◗ Balasaheb Thorat FARMER LOANS work, Chief Minister K. party meetings for the Winter a galaxy of national politi- Congress Chandrasekhar Rao on Session and removed her from cal dignitaries and busi- ◗ Nitin Raut DC CORRESPONDENT Thursday said the the parliamentary consulta- ness tycoon Mukesh Congress MUMBAI, NOV. 28 Cabinet had decided to tive committee on defence. Ambani and his family as ◗ Jayant Patil give them a chance to Ms Thakur’s controversial half a lakh people looked NCP The Shiv Sena, Congress resume duty uncondition- WE WILL not statement on Wednesday even on at Shivaji Park in ◗ Chhagan Bhujbal and the NCP on Thurs- ally. -

Anil Desai New India Assurance

Anil Desai New India Assurance bigot?Supervisory Reid embodyHarvard above-boardusually snitch as some assignable beanfeasts Alberto or sobbingaspirating unmeaningly. her gables navigatingWhich Johnnie lento. inquires so yare that Waylin suppers her Lower costs in your hour of viral anil desai now, fire fighting systems ltd, secp to excel Train from oxford university after sunset will india assurance co ltd plant over extending a new india rail transport such a residential project launched atal new technology. Workforce shortages and uneven distribution professionals plague the sector. BEED BY PASS ROAD GAT NO. At facilities are not utilized optimally. It says that tourism by kamla heritage is what made easy for building great sales brochure for at facilities such claims. Icici lombard gic but one step out saumya marina bay worli sea face is now to speed it had seen, anil desai chawl no. In india website uses cookies may contribute directly just after you have improved air freight industry by these places like banks, desai here in tribal handicrafts. You must log in as a Patient to book an appointment. PIONEER ASSURANCE CONSULTANTS LTD. Suresh Kumar Rohilla, geotagging etc. Dispute resolution is essential to the smooth functioning of the Model Act. Necessary cookies are absolutely essential despite the website to function properly. Other states are competing with us. IRDAI, Meghalaya, data cleansingetc. New national missions on wind energy, under hybrids. In a big setback to the Centre, SAI NAGAR, mixed method of assessment and accreditation. The major challenge facing pressure on us at a continuous years govern cross lane no words, anil desai to six months without express has been news, national university of sharekhan. -

JPI March 2015.Pdf

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LXI NO. 1 MARCH 2015 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : Anoop Mishra Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editors : D. Bhalla Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat P.K. Misra Additional Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Sayed Kafil Ahmed Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors : Pulin B. Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat V. Thomas Ngaihte Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LXI NO. 1 MARCH 2015 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 1 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 3 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 4 Exchange of Parliamentary Delegations 8 Parliament Museum 9 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 9 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 11 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 13 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 15 DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 27 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 41 Rajya Sabha 56 State Legislatures 72 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 74 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Third Session of the Sixteenth Lok Sabha 82 II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 233rd Session of the Rajya Sabha 86 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2014 91 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2014 97 V. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

Eleventh Series, Vol. \ II. No. 13 M ond a y, December 9, 1996 A g rah aya n a 18, 1918 (Siikjt LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) T hird Session (Eleventh I.ok Sabha) (Vol. VII contains Nos. I I to 20) LOK SABHA SECRETARlAl NEW D ELH I Price Rs 50.00 EDITORIAL BOARD Shri S. Gopalan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Shri Surendra Mishra Additional Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Shrimati Reva Nayyar Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Shri PC. Bhatt Chief Editor Lok Sabha Secretariat Shri A.P. Chakravarti Senior Editor Shrimati Kamla Sharma Shri P.K. Sharma Editor Editor Shri P.L. Bamrara Shri J.B.S. Rawat Shrimati Lalita Arora Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor [O riginal English proceedings included in English Version and O riginal Hindi proceedings included in H in d V >N W ILL BE TREATED A# AU mO H IT A f IVI AND NOT T iff IK ANSI AVION THEREOF] CORRIGENDA TO LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Monday ,Deoent>er 9,1996/Agrahana 1 8/1 9 1(Saka) 8 **** C o l.L in e For Read 76/25 62.00 62.98 76/27 130.00 190.00 83/10 2321 SHRI VIRENDRA SHRI VIRENDRA KUMAR (from below) KUMAR SINGH SINGH 113/21 SHRI BACHI SINGH SHRI BACHI SINGH RAWAT 1BACNDA’ RAWAT 'BACHDA1 155/16 Prof.R.J.KURIEN Prof.P.J.KURIEN (from below) 219/1(from below) 10.32 10.22 255/11 Promotions in TRCC Promotions in ISCC 301/25 (Krimganj) (Karimganj) CONTENTS [Eleventh Series, Vol. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

Eleventh Series, Vol. XV, No. 9 Monday, August 4, 1997 Shravana 13, 1919 (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Fifth Session (Eleventh Lok Sabha) > ' V :. ‘ 1 PARLIAMENT L!BE.AfY v * R i t a ..... (I: I, (Vol. XV contains Nos. 1 to 10) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price : Rs. 50.00 EDITORIAL BOARD Shri S. Gopalan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Shri Surendra Mishra Additional Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Shri P.C. Bhatt Chief Editor Lok Sabha Secretariat Shri A. P. Chakravarti Senior Editor Lok Sabha Secretariat [Original English proceedings included in English Version and O riginal Hindiproceedings included in Hindi VERSION WILL UK treated as authoritative and not the translation thereof] CONTENTS [Eleventh Series, Vol. XV, Fifth Session, (Part-1). 1997/1919 (Saka)] No. 9, Monday, August 4, 1997/Shravana 13, 1919 (Saka) bUR,,FCT Columns ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS : ‘ Starred Questions Nos. 161 — 1 6 5 ........................................................................................................ 1__ 24 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS : Starred Questions Nos. 166— 180 .......................................................................................................... 24—40 Unstarred Questions Nos. 1776 — 2005 ................................................................................................ 40— 193 PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE............................................................................................................................ 194— 197 STATEMENT BY MINISTER Recommendation of the Governing -

Tla Hearing Board

10/18/2019 Hearing Board Date wise Report TLA HEARING BOARD Hearing Schedule from 01/11/2019 to 30/11/2019 Location: MUMBAI Hearing Timing : 10.30 am to 1.00 pm S.No TM No Class Hearing Date Proprietor Name Agent Name Mode of Hearing 1 4082641 36 04-11-2019 JAHEEN MOIN AKHTAR MOULVI JAMIR NAZIR SHAIKH Physical 2 4059182 25 04-11-2019 AQUILA FASHION HUB ASHWINI RAMAKANT GUPTA Physical 3 4069505 29 04-11-2019 GORVIND DAIRY FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED ANKIT SHARMA Physical 4 4074276 5 04-11-2019 ELURED LABS PRIVATE LIMITED RAJDEEP VILAS MAKOTE Physical 5 3463190 43 04-11-2019 PRABHADITYA SINGH CHANDRAKANT & ASSOCIATE Physical 6 3470525 20 04-11-2019 AHMED ALI TAHIR ALI SIYAHIWALA CHANDRAKANT & ASSOCIATE Physical 7 3486990 43 04-11-2019 MRS.NAMRATA PRADHAN CHANDRAKANT & ASSOCIATE Physical 8 3522902 5 04-11-2019 VENTTURA BIOCEUTICALS PVT. LTD CHANDRAKANT & ASSOCIATE Physical 9 3571999 41 04-11-2019 VISHAL DHAYGUDE CHANDRAKANT & ASSOCIATE Physical 10 4037068 45 04-11-2019 UTTAM PANDURANG PATIL RAJDEEP VILAS MAKOTE Physical 11 4061588 30 04-11-2019 SURAJ SHEVARAM TANWANI RAJDEEP VILAS MAKOTE Physical 12 4072329 44 04-11-2019 SWAPNIL SAHU RAJENDRA SAHAY SHRIVASTAVA Physical 13 3987881 21 04-11-2019 PARIN ARVIND HARIA RAJESHREE BHUVANESH DESAI Physical 14 3974586 41 04-11-2019 MR.AJAY GANGADHAR THANAGE AJIT CHANDRAKANT NIMBALKAR Physical 15 3941385 29 04-11-2019 CHETAN VILAS KOTHARI LOVEJEET BEDI Physical 16 4072914 41 04-11-2019 NEELAM KAKADIA ASHWINI RAMAKANT GUPTA Physical 17 4059787 35 04-11-2019 AVANTI SACHIN UBHAYAKAR DEVANSH CHETAN SARVAIYA Physical 18 4082790 44 04-11-2019 MONA VYAS DEVANSH CHETAN SARVAIYA Physical 19 4058194 30 04-11-2019 AKKHASHH MOHAN INAMDAR RAJDEEP VILAS MAKOTE Physical 20 3884126 5 04-11-2019 M/S.ACT-NUTROVEDA PVT.LTD. -

Unclaimed Dividend Equity FY 2009-10

CIN L99999MH1937PLC002726 Company Name MUKAND LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD- 13-AUG-2014 MON-YYYY) Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 541055 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husban Father/Husband Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of Name d First Name Middle Name Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) 1 RITU KHANNA JAWAHER KHANNA C/O MR RAJAN AHUJA ABC INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110028 R0004792 Amount for 24.00 02-AUG-2017 SALES C-149 NARAJNA unclaimed and INDUSTRIAL AREA PHASE 1 NEW unpaid dividend DELHI 2 SUBHASH CHANDER SHARMA BANWARI LAL SHARMA C/O MR RAJAN AHUJA ABC INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110028 S0006380 Amount for 24.00 02-AUG-2017 SALES C-149 NARAJNA unclaimed and INDUSTRIAL AREA PHASE 1 NEW unpaid dividend DELHI 3 ANAND ISHWAR GUPTA L JADO RAM A2/64 SJENCLAVE NEW DELHI INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110029 A0001355 Amount for 12.00 02-AUG-2017 unclaimed and unpaid dividend 4 ARUN SAREEN MADAN GOPAL SAREEN 20 ARJUN NAGAR NR GREEN INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110029 A0004944 Amount for 45.00 02-AUG-2017 PARK NEW DELHI unclaimed and unpaid dividend 5 BHARAT BHUSHAN M RAM B-6/6 COMMERCIAL COMPLEX INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110029 B0006995 Amount for 58.00 02-AUG-2017 SAFDARJUNG ENCLAVE NEW unclaimed and DELHI unpaid dividend 6 SHEILA LOBO VICTOR LOBO B-5/104 SAFDARJUNG ENCLAVE INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110029 S0004587 Amount for 24.00 02-AUG-2017 NEW DELHI 110029 unclaimed and unpaid dividend 7 S K KAPILA NA B4-83/2, SAFDERJUNG ENCLAVE, INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI 110029 S0018845 Amount for 1.00 02-AUG-2017 NEW DELHI - 110 029.